Madam Begue’s by Henry Voigt

Culinary tourism got a jump-start in New Orleans during the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in 1884-85. Visitors were introduced to Creole dishes that blended French, Spanish, West African, and Choctaw influences, among others. Seemingly overnight, the unique cuisine and signature cocktails of New Orleans became major tourist draws, marking a pivotal moment in the city’s gastronomic history.

One of the restaurants the well-heeled tourists discovered was a small establishment named Madame Begue’s. It served a set meal at 11:00 a.m. for butchers in the French Quarter and dockworkers. It was called a “second breakfast,” even though it resembled a large, midday meal served an hour early for the men coming off work.

The restaurant could accommodate up to thirty guests at its two communal tables. By 1898, the New York Sun reported “nine people out of ten that visit New Orleans have heard of Begue’s.” When German-born Elizabeth Begue (née Kettenring) died in 1906, it was reported in newspapers across the country. Her Creole husband, Hippolyte Begue, married his former wife’s assistant and the restaurant remained in operation for another eleven years. The postcard attests to its status as a quaint tourist attraction.

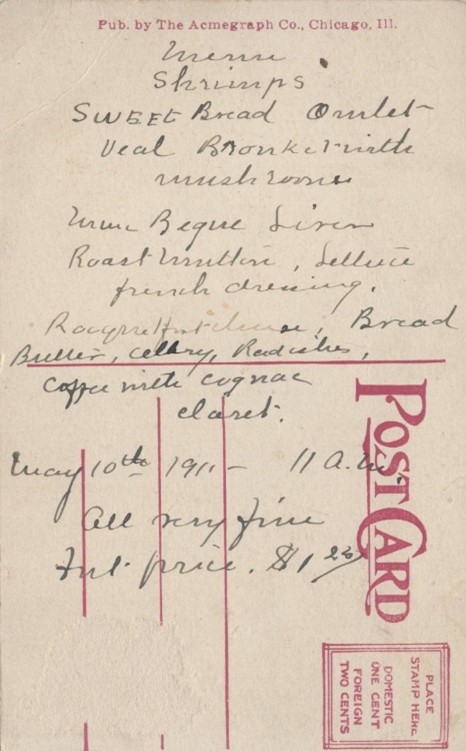

While Begue’s did not have a menu, a guest wrote down the bill of fare for May 10, 1911 on the back of this postcard. It happened to be a Wednesday when liver was typically served. The liver was sautéed in butter and served with fried onions and bacon, eliciting rapturous praise. “Madame, your liver touches my heart!” wrote author William Sydney Porter in the guest book. (It was in New Orleans where Porter picked up the pen name, O. Henry.)

Another specialty was the immense omelets that Hippolyte Begue presented to his guests. On these occasions, the omelets were filled with sweetbreads. After about three hours, the meal ritually ended with a cup of strong coffee that was sweetened with two lumps of sugar and flambéed with Cognac. The prix fixe was $1.25, including wine.

***

The Elkhorn Tavern by David de Soto

The original Elkhorn Tavern in northwest Arkansas was built around 1833 by William Reddick and his son-in-law, Samuel Burks. In 1858, Burks sold the house and the 313 acres to Jesse and Polly Cox for $3,600. Cox made several improvements to the tavern, including adding white-painted weatherboarding to the exterior and a set of stairs to the upper porch. The stairs allowed members of the Benton County Baptist Society, to meet in the building without having to go through a “public house.” Another addition was a set of elk horns that Cox placed on the ridgepole, which gave the tavern its name.

Prior to the Civil War, the house was used for many purposes, including a house of worship, inn, post office, and trading post, although it was well-known locally as a stop for the overland stage. During this period, the tavern was described as a place “of abundant good cheer.”

In February 1862, the fields surrounding the tavern were transformed into the Federal army’s main supply camp. During the Battle of Pea Ridge, the tavern served as a field hospital and, for a brief time, as Confederate General Earl van Dorn’s headquarters. Polly Cox, her son Joseph, his wife Lucinda, and the two youngest children, Elias and Franklin, stayed in the tavern’s cellar during the battle. Although it was hit many times, once by a cannonball that hit the upper floor, the tavern survived the battle intact.

After the battle, the Federals used the tavern as a headquarters and military telegraph station, until it was burned around January 1863 by Confederate guerrillas. Joseph Cox rebuilt the structure on the original foundations soon after the war’s end. As hundreds of veterans and their families returned to the battlefield, Cox ran a small museum with battle artifacts hung on the walls. The structure went through many modifications and changes until it was transferred to the National Park Service on March 7, 1960. The structure has since been restored to its approximate wartime appearance.

***

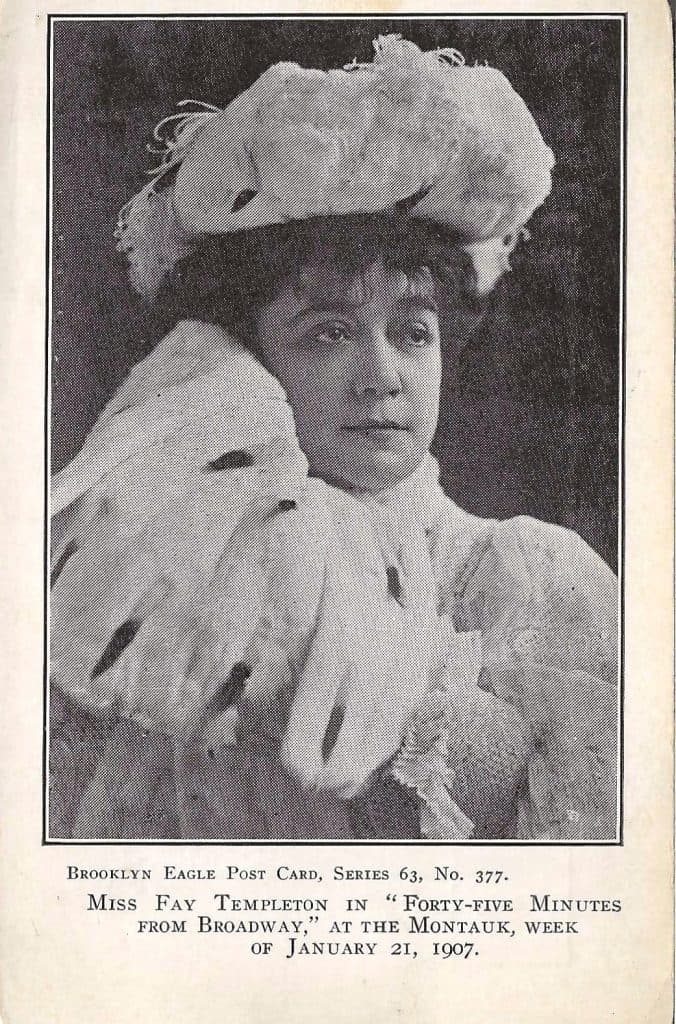

Fay Templeton at the Montauk Theatre by Nancy Harris

It was Christmas day, 1865, when John J. Templeton, a hard at-work vaudevillian in Little Rock, Arkansas, got the best present a father could ask for – the birth of a daughter who he named Fay.

Fay followed in her parent’s footsteps and became one of America’s most loved personalities. At age three, she dressed as Cupid and sang fairy tale songs between the acts of her father’s plays. Gradually, she was included in other productions as a bit player, and then at age 5 she had lines to recite. At age 8, she played Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As early as 1890, she toured with her own Templeton Light Opera Company as an accomplished actress, singer, songwriter, and comedian.

Her Broadway debut in the title role came in 1900. She surpassed everyone’s expectations in the popular theater of the day. Her popularity skyrocketed when she was seen in the company of Samuel S. Shubert, the middle son of New York theater owners, but that ended when Sam died of injuries sustained in a railroad accident in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Templeton’s most memorable role was in George M. Cohan’s 1906 production, Forty-five Minutes from Broadway, in which she introduced two of its hit songs: “Mary’s a Grand Old Name” and “So Long, Mary.”

Forty-Five Minutes From Broadway was a three-act musical that Cohan composed about the town of New Rochelle, New York. The title reflects the three-quarters of an hour it takes a train to reach Broadway from the New York and New Haven Railroad station at New Rochelle.

The show opened on New Year’s Day 1906, at the New Amsterdam Theatre and ran for 90 performances. It had two leading roles: Mary Jane Jenkins was played by Templeton, and Kid Burns was played by Victor Moore. Moore was one of Broadway’s leading men from the late 1920s and well into the 1930s.

On August 2nd, after “45-minutes” closed on March 17, Templeton married William J. “Ridgely” Patterson of Pittsburg, a wealthy industrialist, and later that year she semi-retired. She did, however, make one return to the stage in a 1912 revival of H.M.S. Pinafore. She made her only film, Broadway to Hollywood, in 1933 and later that year appeared in her final Broadway show, Jerome Kern’s Roberta, where she introduced the wildly popular song, “Yesterdays.”

Fay Templeton died in October 1939 at age 74.