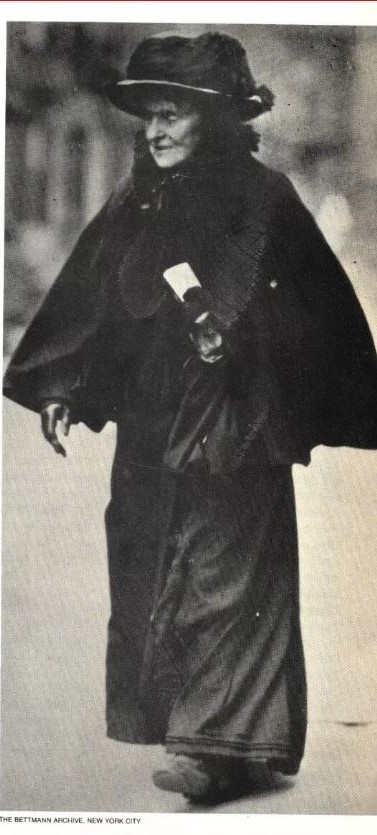

The press called her “The Witch of Wall Street” and several other less-than-flattering names. It was what the press did in the 1880s to the woman who had a great deal of money and used it to make even more.

Henrietta Howland Robinson was born in 1834 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to a wealthy Quaker family whose generational roots were in whaling, shipping, and banking. From an early age her family, particularly her grandfather, taught “Hetty” the rudiments of business.

The family was fractious and her parents distant. At age two she was sent to live with relatives, at age ten she was sent to a strict Quaker boarding school, and at 15 she was sent to a Boston finishing school to learn the social graces and prepare to marry.

When Hetty was 20, she was sent to live with relatives in New York City, where she was expected to find a husband. Her father gave her $1,200 for living expenses. A year later she returned to New Bedford and reported that she had spent only $200 on expenses and had invested the rest in high-quality bonds. And made money.

When her father sold the whaling and shipping businesses and moved to New York, Hetty worked with him in his interests in real estate and banking.

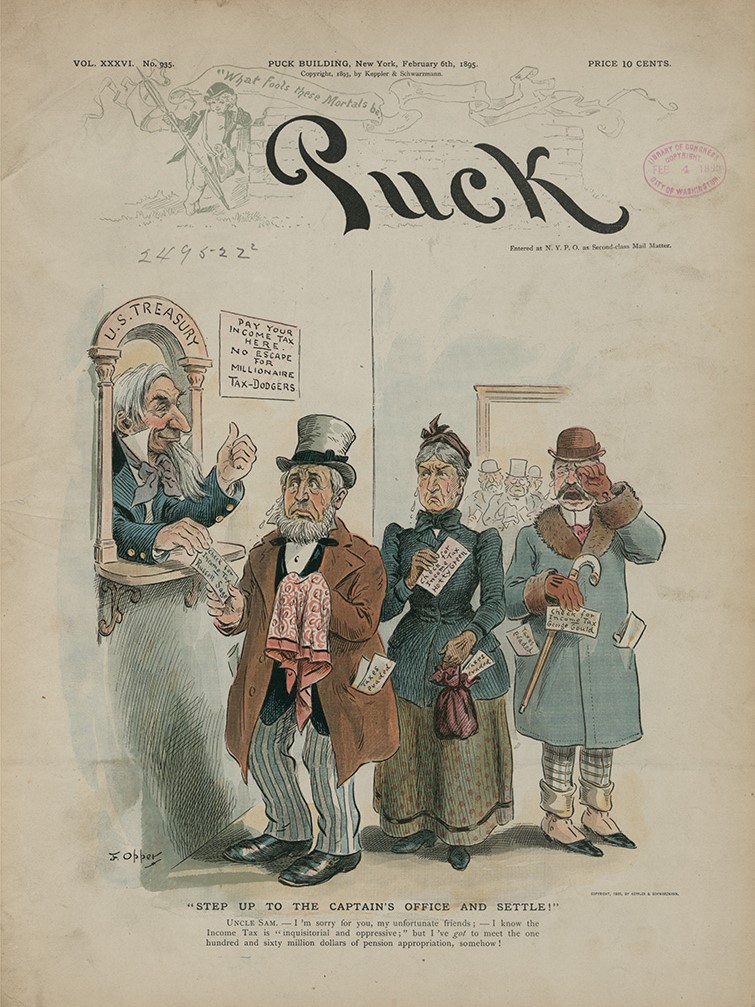

In 1865 her father died and soon her aunt Sylvia died as well. Hetty was enraged over the terms of her aunt Sylvia’s will and began a lawsuit contesting the will, litigation that was still going in 1895 and included allegations that she had forged her aunt’s signature to a later will. (She lost, eventually.)

In 1867 Hetty married Edward Henry Green, a Vermont native who had spent almost two decades in London making his own fortune. Their honeymoon in London extended to seven years, with Green investing in banks and Hetty buying government bonds and railroad stocks.

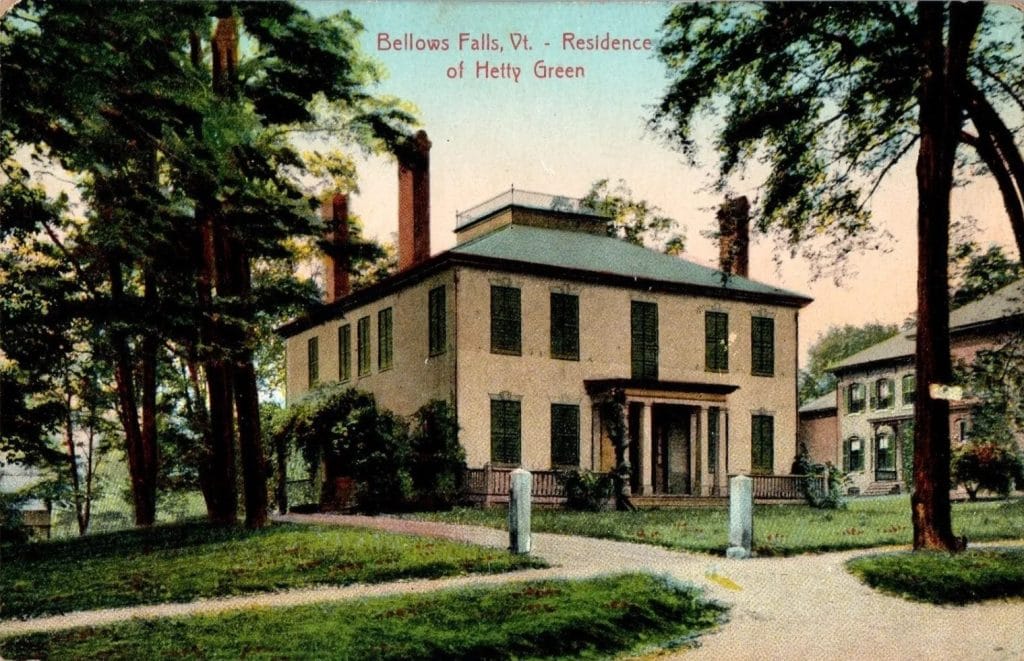

On their return to America, they lived in Edward’s hometown of Bellows Falls, Vermont, with their two children, Edward and Sylvia.

The contrast of investing styles between austere Quaker Hetty and the risk-taking Edward Green was stark. Wisely, Hetty had insisted as a condition to marriage that Edward sign a pre-nuptial agreement giving her control of her money.

Press coverage of Hetty’s austere dress and more-than-frugal habits took a serious turn when her son Ned developed complications from a childhood leg injury. Green, sensational reports had it, refused to pay a doctor to treat the boy and as a result the leg had to be amputated. No hard evidence of this was cited but it is known that she did take the boy to numerous specialists. The story of the amputation was true.

Other stories:

During the Panic of 1884, Edward overextended himself in railroad stocks. His account with the private bank of John J. Cisco had margin debt that he could not cover, but Hetty had cash in the bank. When Hetty moved to transfer her cash, Cisco demanded she first cover Edwards losses. She reluctantly did but the marriage suffered, and she banished Edward and put him on an allowance. He became known to the press as Mr. Hetty Green.

Green disliked paying taxes, to the extent that she moved out of New York City, first to the city of Brooklyn and then to Hoboken, New Jersey and lived in a $19-a-month apartment under the assumed name of “C. Dewey,” after her beloved Skye terrier.

Green is sometimes credited with first articulating the concept of the “value investor.” In a 1905 interview she said “I buy when things are low and no one wants them. I keep them, just as I keep a considerable number of diamonds on hand, until they go up and people are anxious to buy … I never speculate. Such stocks as belong to me were purchased simply as an investment, never on margin.”

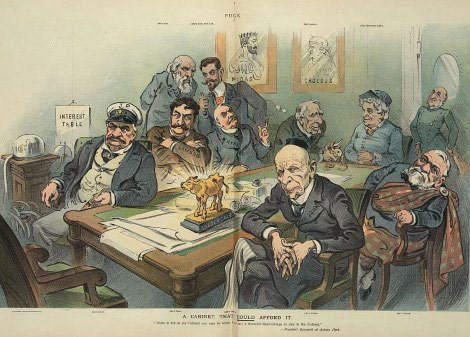

She was a secret philanthropist, donating to Barnard College Nurses Home among others. That willingness to extend beyond her own business came when she sensed the impending collapse that led to the Panic of 1907. J. P. Morgan is rightly credited with assembling the financiers who saved the American economy, but Hetty Green was the only woman at the table.

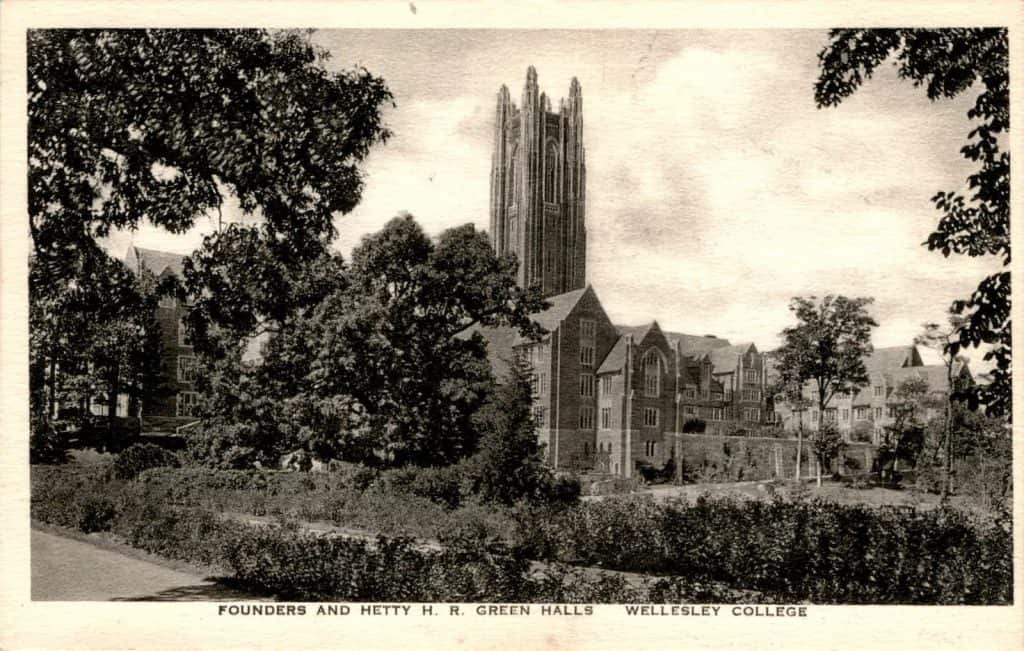

Hetty died on July 3, 1916, leaving the vast bulk of her estate estimated at $100 million to her children. Ned and Sylvia donated the money for the construction of the H. R. Green Hall at Wellesley College, a building that consolidated the administrative and academic functions of the college that had been scattered around the campus after a fire in 1914.

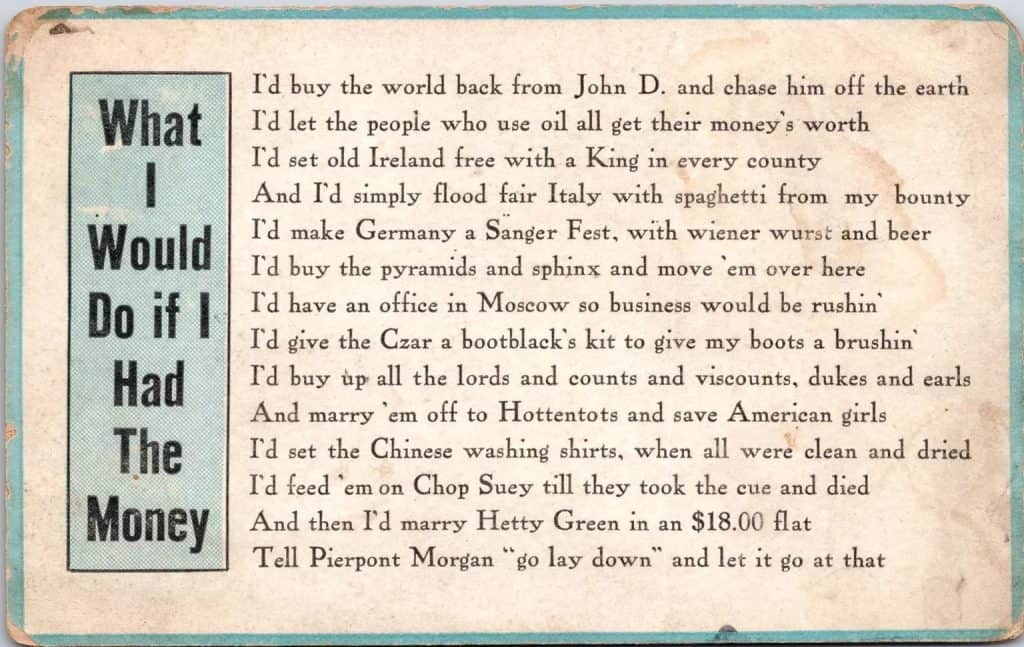

Thank you. If I had bought the “What would I do….” postcard I would have been keen to learn who Hetty was and about her US$18 flat. A great card and an interesting back story.

I have a ” What Would I Do” postcard, but I hadnt the chance or thought, to look Hetty up. Thanks for adding a bit of interesting history to my card. Seems there are a few other stories of women who maneuvered their way up the ladder in a man’s world in that era. I just finished a book on Arabella Huntington. From rags to wealthiest woman in the country. Cunning lady.

I was aware of the legend that Hetty was so miserly that she let her son lose his leg, but didn’t realize she had been a “secret philanthropist”.

Love the story of Hetty Green. I also love the cover from Puck magazine. The 1894 income tax was later declared unconstitutional as a direct tax. Why it would be controversial might be hard to understand for modern eyes as it provided for only a 2% tax rate on incomes over $4,000, and affected only about 2% of the population.

I am attaching a post card of Hetty Green’s Home in New Bedford. The building housed New Bedford’s first hospital, St. Joseph’s, which was conducted by the Sisters of Mercy commencing in 1876. The hospital was short lived and for over one-hundred years served as a convent. The section of the building on the left, with the cross at the top, was added by the nuns. The convent closed about 35 years ago and now houses various social-service institutions.

Mr. Meggison’s card.

Very interesting bio. Thanks!

Many years ago I read the story of the life of Green and her daughter and son and the millions she acquired. Nowhere in the book ( name of which I can not remember) was there any reference to her being a ‘secret philanthropist’, instead it focused on the irony of the dispersal of that great fortune. By the way, what portion of the building is the home? Thanks for an interesting story.