Kaya Fellcheck

Sir William Wallace

The curtain opens. There stands these three men. Each raises his right hand and says,

My name is William Wallace

My name is William Wallace

My name is William Wallace

Who is the real William Wallace?

After reading this I guarantee that you could be a panelist

on the “To Tell the Truth” TV Game show hosted by Gary Moore of the 1960s.

If somewhere in the credits of the 1995 Hollywood blockbuster Braveheart you saw the caveat, “Based on a True Story” you should disbelieve at least the last two words. The movie was a true cinematic achievement, but Gibson himself called his epic a “historic fantasy.”

“Fantasy,” is the essential word in this case for even the name Braveheart was taken from an event that happened twenty-four years later when Robert the Bruce lay dying in the manor house at Cardross, nearby Dumbarton, Scotland. Ergo, the title should be credited to a dead Robert the Bruce, rather than to a living William Wallace.

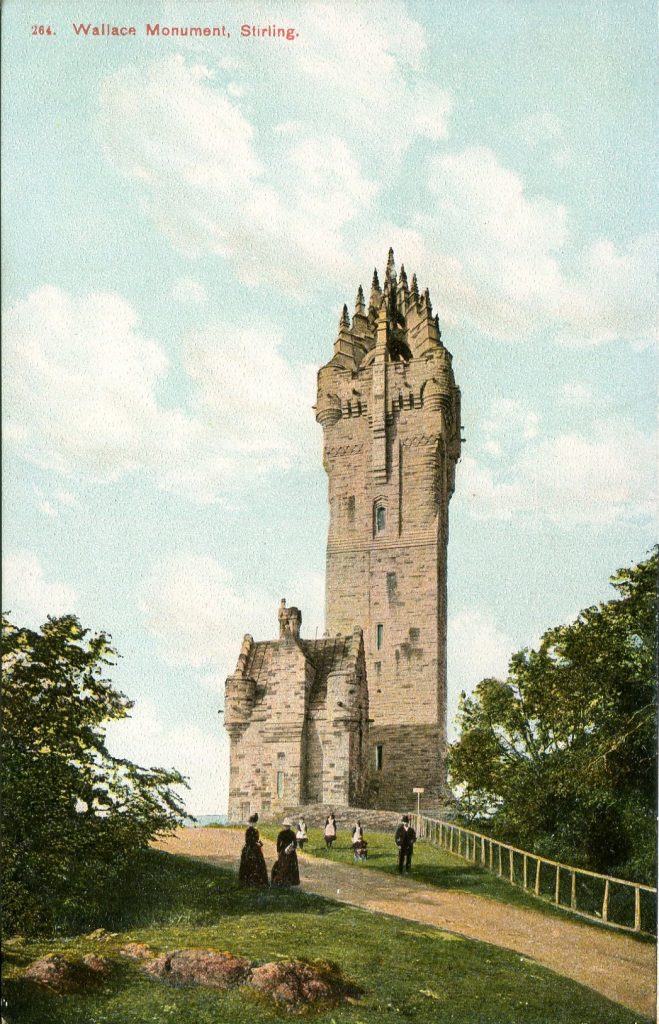

Regardless, even today, the name Wallace in all of Scotland conjures the legend of a man who was no ordinary hero. In 1861, the very best of Victorian workers set out to build a monument to Sir William on a hill-top 42 miles northeast of Edinburgh.

The national monument was designed by the Glasgow architect John Thomas Rochead. Rochead had just completed the Royal Arch in Dundee and was the popular choice for the new and grandest tribute to the memory of Wallace. The project took eight years to complete. It opened officially in 1869. It is the newest of more than twenty monuments honoring the 13th-century hero.

When Henry III of England died in 1272, his son and successor Edward I, was on his way to the Holy Land during the ninth crusade. Edward was informed of this father’s death but made no effort to affect a quick return. When he did return in 1274, he enjoyed his coronation on August 19th. Shortly after, his subjects dubbed him Edward Longshanks, but to those outside his court he came to be, Edward, Hammer of the Scots.

At that time the Kingdom of Scotland enjoyed the status of a tributary state to the English throne. It is an arrangement where one government has control over another’s foreign policy. Tributary states, by tradition enjoy internal autonomy, which often leads to rebellion when the demands of the foreign entity exceed what is reasonable – such as when taxes and other freedoms are infringed.

Edward sat for less than a year before he unilaterally imposed a laundry list of revisions on English Common Law. His revisions were nonsensical and many of them forged a series of minor rebellions – notably in Wales and Scotland.

The Welsh and Scottish rebellions caused Edward to turn his attention to military affairs. The English successfully suppressed the Welsh rebellion and settled the one in Scotland, but very little changed. Governmental alliances remained strained as large segments of the populist schemed and connived their way into battles against an enemy intent on the complete conquest of Scotland.

Edward thought he was the victor in the Scottish War when he left England for a State Visit in Flanders. By the mid-point of 1297, new rebellions festered and emerged under the leadership of Andrew de Moray in the north and William Wallace in the south.

On September 11, 1297 a large English force under the leadership of the Earl of Surrey was routed by a much smaller Scottish army led by Wallace and Moray at Stirling Bridge. The news of the English defeat sent the English court into convulsions. Preparations for a retaliatory campaign began immediately, even in the king’s absence.

When Edward returned from Flanders, his first action was to revenge the 1297 English defeat and did so successfully on July 22, 1298. It all happened when he defeated Wallace’s forces at the Battle of Falkirk. Then by 1304, most of the other nobles had pledged their allegiance to Edward enabling him to re-take Stirling Castle.

Finally in 1305 Stirling Castle fell to the English, which brought the rebellion under their control when Sir John de Menteith betrayed Wallace and turned him over to the English, who had him taken to London where he was publicly executed.

Legend insists that the under-dog should win, at least in the “brave hearts” of the Scottish population. Edward, after all was a loathsome man, yes, he was tall, but also skinny and frail. William, on the other hand stood six-feet five inches tall, had broad shouldered and presented a ruddy complexion. I ask you, who would you want as your hero?

Oh, did you ask, “Why did Braveheart paint his face blue?”

That part of the Braveheart story isn’t totally wrong, except the blue-face tradition dated back to Roman times and was well out of practice when Wallace was fighting the English. When your curiosity gets the best of you and you read the early history of Scotland, you’ll learn that there was a second Roman Emperor who built a wall across Scotland. Hadrian did it first in AD 122, but then in AD 142 the Emperor Antonine Pius ordered a second wall across a part of Scotland called the Belt. The blue face painting tradition came from those who lived north of the Antonine Wall. They were a savage people known as the Picts. The Picts used blue face paint when fighting the Romans. That was twelve-hundred years before William Wallace.

So as Gary Moore always asked, “Will the real Sir William Wallace please stand?”

i fondly remember Garry (the correct spelling) Moore as the host of “To Tell the Truth”.

I think this guy was one of my grandpa’s !!

That’s pretty cool !!

Lady Margret Sterling of Keir was one of my grandma’s.