Editor’s Staff

The Lion at Waterloo

The battlefield at Waterloo is a must for the history traveler. Always and forever those who speculate on history will ask, “What if…?” Waterloo is likely the first place the question, “What if Napoleon had won; would we be speaking French?” was asked. Like the question, the answer is unfathomable, but there is always a monument.

The first known mention of Waterloo as a village in Belgium, was at the onset of the 12th century. The location was given as near the wood at the south-east edge of Brussels. As a woodland, it was favored by the imperial family as their private hunting grounds. In the years that followed the later named, Sonian Wood, would figure in the legend of another world-famous event – a battle fought between the forces of the British and the French.

The combatants, each for other reasons, achieved historical stature deserving serious scholarship. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, was a 46-year-old career soldier who in the decades after the battle would put an end to his military career and turn to politics to serve as Britain’s Prime Minister. His opponent, Napoléon Bonaparte, also 46, enjoyed success in the military and as a political leader gained prominence during the 1789 French Revolution and in 1804 was declared Emperor of France.

Wellington with his victory at Waterloo, ended the Napoleonic Wars. And, as it is the victor who writes the history, so does he erect the monuments.

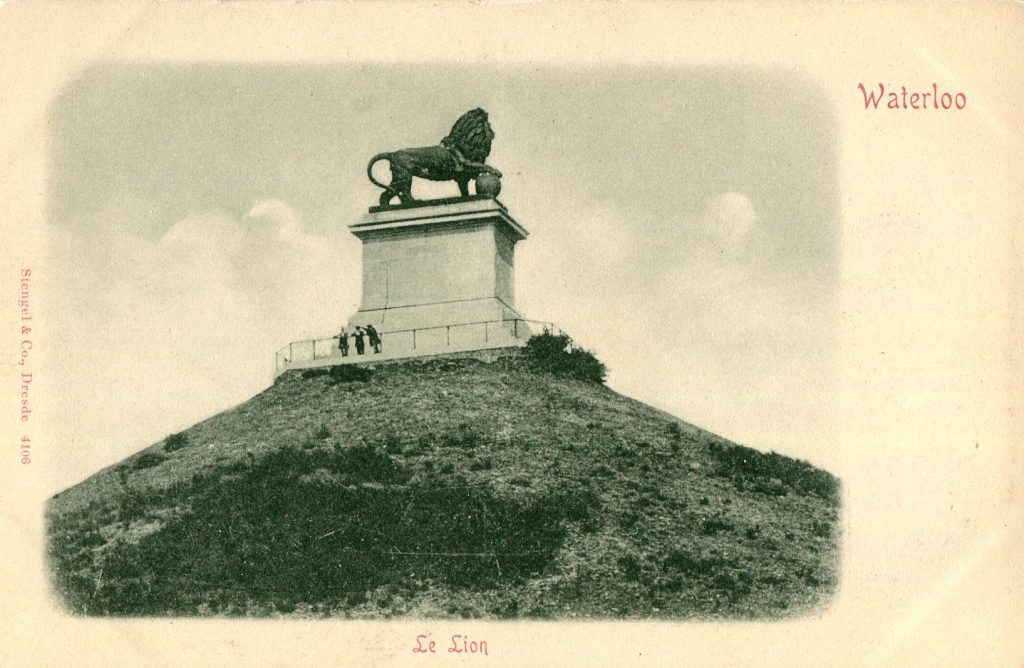

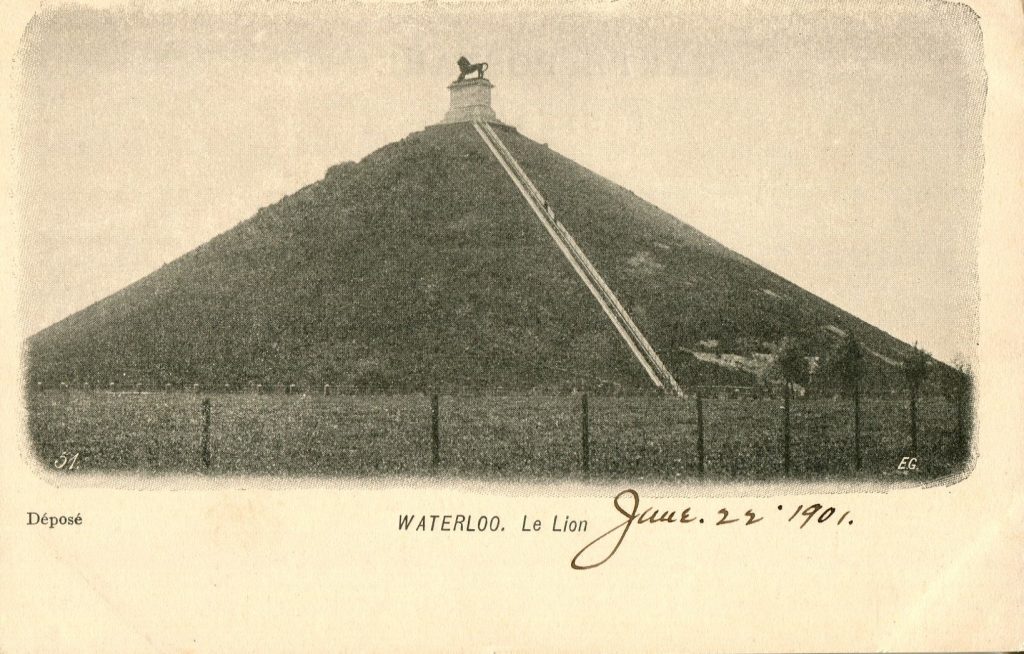

The Lion of Waterloo is named in at least four languages – French, Walloon, Dutch, and English. Two-hundred, twenty-six steps lead up an artificial mound to the monument where the lion stands to honor the memory of a battle fought in 1815.

The artificial mound constructed of earth from parts of the battlefield, is 140 feet in height and at the base just more than 1,700 feet in circumference. An interesting aside concerning the mound came from Wellington, himself, who in 1828 visited the site of his victory and quipped, “They have altered my field of battle!”

Completed in 1826 at the behest of William I, the architect Charles Vander Straeten designed the monument. It is meant as a symbol of an allied victory rather than a glorification of a lone individual. It was thoroughly documented by artist drawings, etching and engravings.

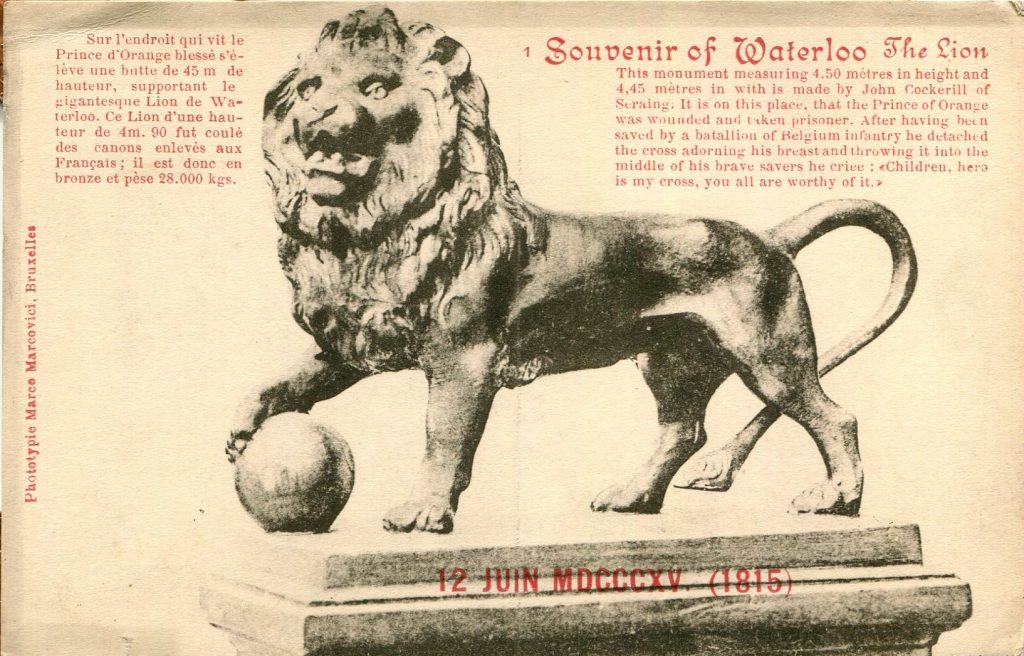

The lion stands on a stone pedestal facing west. The sculptor, Jean-Louis Van Geel has suffered the critics, through the years, that his work too closely resembles the century’s old de Medici lions on display in Florence, Italy, since the 1790s.

Coincidentally, a lion appears on the English Royal Coat of Arms, the U.K. Coat of Arms, and the personal coat of arms of the Dutch monarch. In each case the lion symbolizes courage. The Lion of Waterloo’s right front paw is raised and rests on a sphere that is interpreted as global victory.

The statue alone is more than thirty tons. It was cast in nine (one source says seven) sections in Liege and transported to Brussels by barge and then horse drawn wagons to Waterloo. One account of the process speculated that the foundry owner gathered brass from the French cannon that were abandoned on the battlefield.

Today visitors may climb the steps and gain admission to the Waterloo Panorama, a painting of the events in 1815 that is housed in a nearby rotunda completed in 1911.

* * *

While you’re in the area be sure to stop by for lunch at the café across the road at the edge of the Sonian Forest. Take a few minutes to enjoy a meditation at the Church of Saint Joseph, and please don’t miss the castle at Argenteuil, the one-time home of King Leopold III.

Wonder what boots would be called in England had Arthur Wellesley not gained the fame that led to the footwear becoming known as “Wellingtons” or “wellies”.

Don’t know what the real Wellington looked like, but Lawrence Olivier sure looked great in the movie.

Sad that we need such monuments to our never ending wars.

This story makes me want to go visit, have lunch, stop by the church, and climb up all of those stairs

to see the lion, up close. Thanks very mch.