Daniel Hennelly

The Great White Fleet

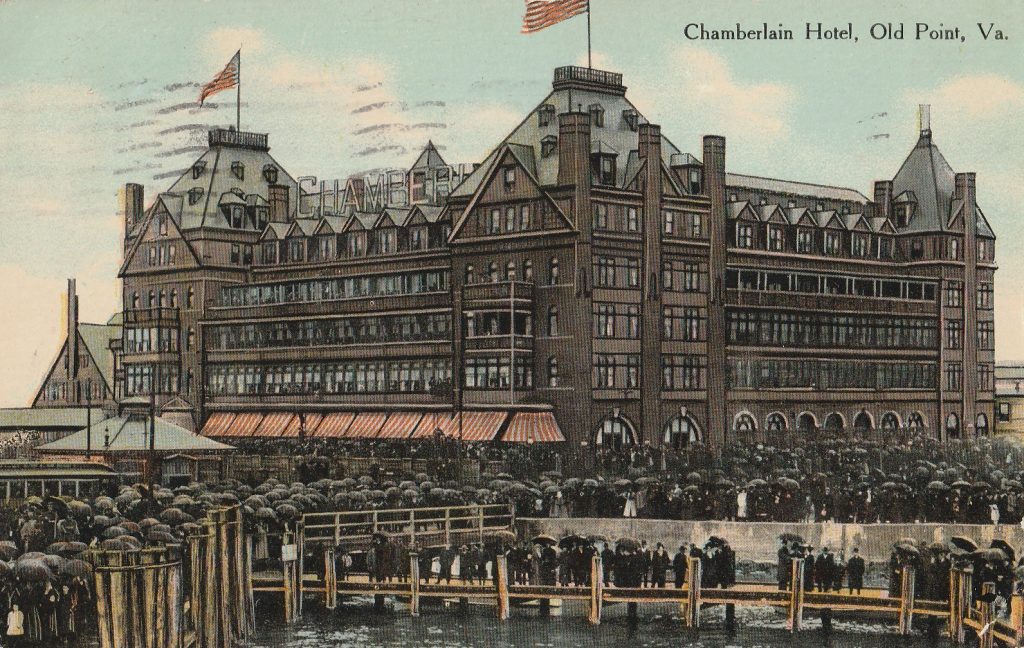

A postcard of the original Chamberlin Hotel, adjacent to Fort Monroe at Old Point Comfort (now Hampton, Virginia), intrigues me. Why was everyone standing in front of the hotel during a rainstorm? Look closely, there are hundreds of black umbrellas in the photo.

Chamberlin Hotel, Old Point, Va.

Hampton [Roads], mentioned above, refers to the body of water where the Elizabeth, Nansemond, and James Rivers converge between Sewell’s Point in Norfolk and Old Point Comfort in Hampton. Situated at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, it is one of the world’s largest natural harbors. Cape Henry is where the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean.

The card was found in 1979 at a postcard show in Richmond, Virginia. It cost twenty-five cents. It’s a divided back postcard, mailed on June 24, 1910. Unfortunately, the back provided no clue about what was happening when the photograph was taken.

From April through November 1907, Norfolk, Virginia, hosted the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition at Sewell’s Point celebrating the 300

th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown settlement. Almost three million visitors attended the exposition, but six million visitors had been projected and the exposition ended as a financial disaster for the backers.

The exposition was held on what is now the site of the Norfolk Naval Base that was established in 1917 at the start of World War I. The Chamberlin Hotel was across Hampton Roads from the site of the exposition.

Norfolk is home to nearly 245,000 Virginians and it has a glorious history. Part of which started April 26

th when President Theodore Roosevelt opened the event, then presided over an international naval review. A photograph of President Roosevelt addressing the opening day ceremony shows the women wearing large hats and light-colored dresses. Not an umbrella in sight.

After the exposition closed, President Roosevelt sent sixteen battleships from the U. S. Navy’s Atlantic Fleet on a voyage around the world to show America’s naval strength and proclaim the United States as a player on the world stage. The fleet steamed out of Hampton Roads on December 16, 1907, with President Roosevelt watching from the presidential yacht,

Mayflower. According to author, Samuel Carter III in his 1971 book,

The Incredible Great White, “Sky and sea were sparkling as the fleet sailed southeast for Trinidad.”

From this, we know the postcard photograph does not depict the Great White Fleet’s departure.

It is also known that the Great White Fleet returned to Hampton Roads on the evening of February 21, 1909. They anchored off Cape Henry and the ships prepared for the parade the next day by slapping on a fresh coat of white paint to cover the grime of months at sea. The ships were coal fired and the soot streaming from the smokestacks coated the white ships.

Businessmen in New York City wanted the fleet to end its voyage there and promised Roosevelt that three million spectators would view the fleet as it steamed up the Hudson River. Roosevelt thought the parade would be a fitting end to his presidency. The Navy overruled him, and the fleet made it grand procession in Hampton Roads as originally planned.

Samuel Carter states, [“…] on February 22, 1909, Washington’s birthday, the President’s yacht

Mayflower took up a position near Cape Henry as Admiral Sperry’s battle fleet at the head of a naval column seven miles long passed in review. As each ship passed the

Mayflower, a salute of twenty-one guns was given, consuming more gunpowder than at the battle of Manila.”

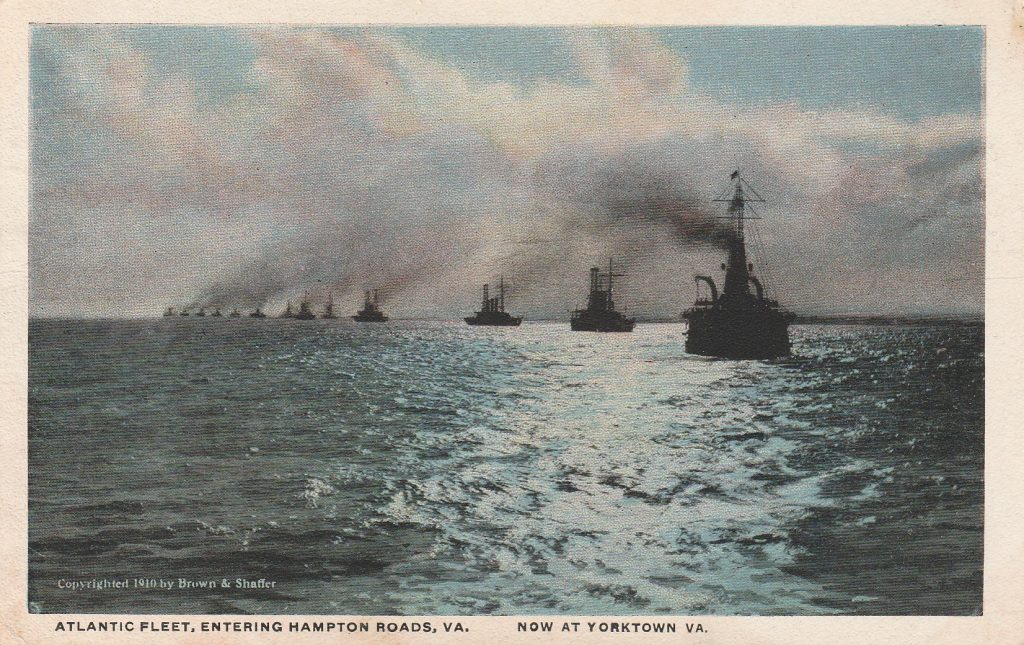

The Atlantic Fleet entering Hampton Roads.

Carter also reports, “The waters off Norfolk and Old Point Comfort were crowded with excursion steamers from Baltimore and Richmond. The weather did not diminish the crowds which swarmed over the Chamberlin Hotel in a competitive fever to be the first to sight the fleet.”

Does mention of the weather imply it was raining?

One Great White Fleet sailor commented on the homecoming, “We hit Hampton Roads on Washington’s Birthday and it was raining. But by golly, we celebrated with hardtack and sow belly dinner that day.” Photographs from the Newport News

Daily Press show crowds standing around the Chamberlin Hotel in the rain confirming the postcard image as part of the fleet’s homecoming.

The voyage of the Great White Fleet lasted fourteen months; they sailed 46,000 miles, visited six continents and twenty-six countries. Its frequent port calls were necessary for refilling the coal bunkers of the battleships. Many of the fleet’s sailors were just off the farm with an average age of twenty years old. In 1904, the Navy had adopted the recruiting slogan, “Join the Navy and See the World.” For those young men, the Great White Fleet’s voyage fulfilled their starry-eyed dreams.

The Great White Fleet

The Fleet, First Squadron, and First Division, commanded by Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry

Connecticut, the Fleet’s flagship, Captain Hugo Osterhaus

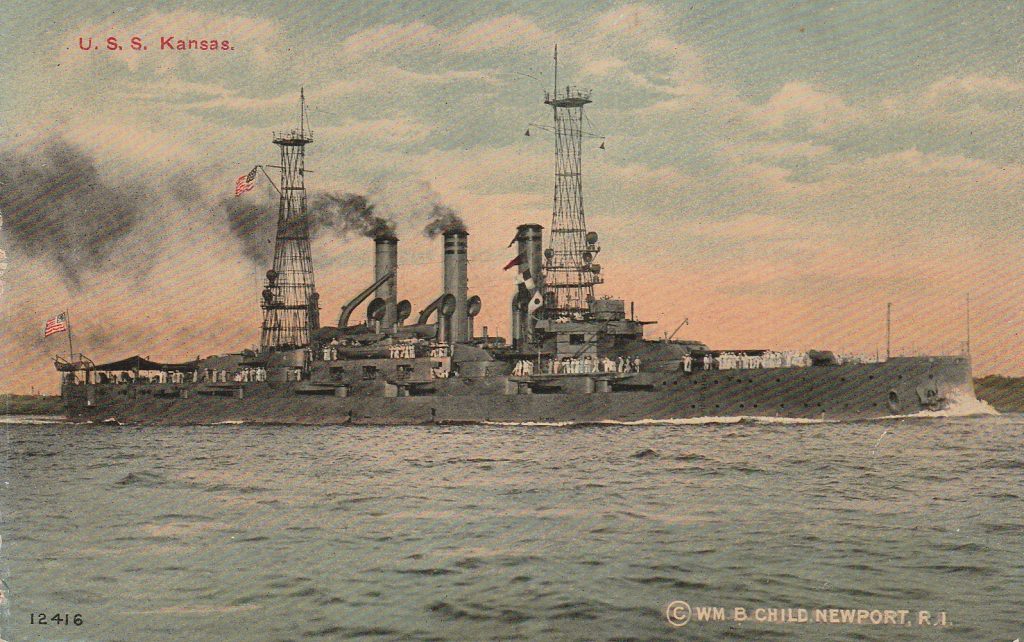

Kansas, Captain Charles E. Vreeland

Minnesota, Captain John Hubbard

Vermont, Captain William P. Potter

Second Division,

Georgia, the Division flagship, Captain Edward F. Qualtrough

Nebraska, Captain Reginald F. Nicholson

New Jersey, Captain William H.H. Southerland

Rhode Island, Captain Joseph B. Murdock

Second Squadron and Third Division, commanded by Rear Admiral William H. Emory

Louisiana, the Squadron flagship, Captain Kossuth Niles

Virginia, Captain Alexander Sharp

Missouri, Captain Robert M. Doyle

Ohio, Captain Thomas B. Howard

Fourth Division, commanded by Rear Admiral Seaton Schroeder

Wisconsin, the Division flagship, Captain Frank E. Beatty

Illinois, Captain John M. Bowyer

Kearsarge, Captain Hamilton Hutchins

Kentucky, Captain Walter C. Cowles.

The Fleet Auxiliaries

Culgoa (a storeship), Lieutenant Commander John B. Patton

Yankton (a tender), Lieutenant Commander Charles B. McVay

Glacier (a storeship), Commander William S. Hogg

Relief (a hospital ship), Surgeon Charles F. Stokes

Panther (a repair ship), Commander Valentine S. Nelson.

The Atlantic Fleet entering Hampton Roads.

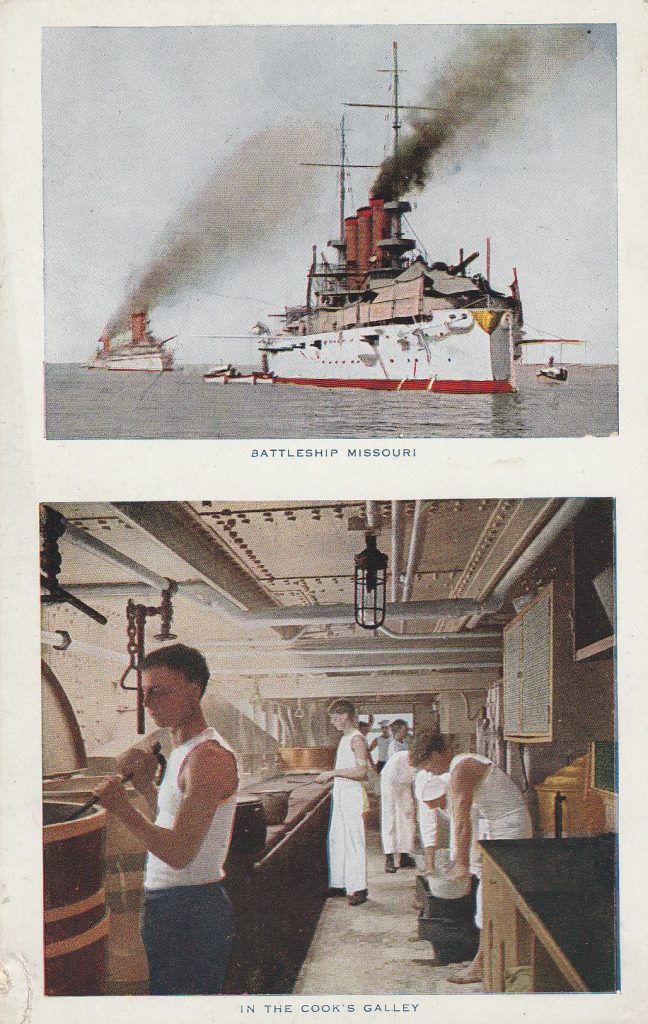

The battleship

USS Missouri painted white with red trim. At President Roosevelt’s insistence, the 16 battleships of the Great White Fleet were painted in their parade colors for the voyage around the world.

Missouri had a crew of almost 600 officers and crew. It took an enormous effort to feed them three meals a day plus midnight rations.

The

USS Kansas painted gray after the voyage of the Great White Fleet. At the time, all the ships of the U.S. Navy were coal fired. The plume of black smoke not only coated the ships with coal-soot, but also gave away the ship’s position to enemy gunners. During World War I, the Navy began converting the fleet to oil. Also converted in the 1920s were the lattice masts. Tripods replaced the latticeworks. The postcard was published by the Souvenir Postcard Company and copyrighted by William B. Child of Newport, Rhode Island in 1910.

Equator-Crossings

[A line crossing ceremony for a person who is sailing across the equator for the first time is a tradition in many national navies of the world, including the merchant marines and commercial freighters and tankers. Such events are also commonly “performed” for passengers on ocean liners and cruise ships.]

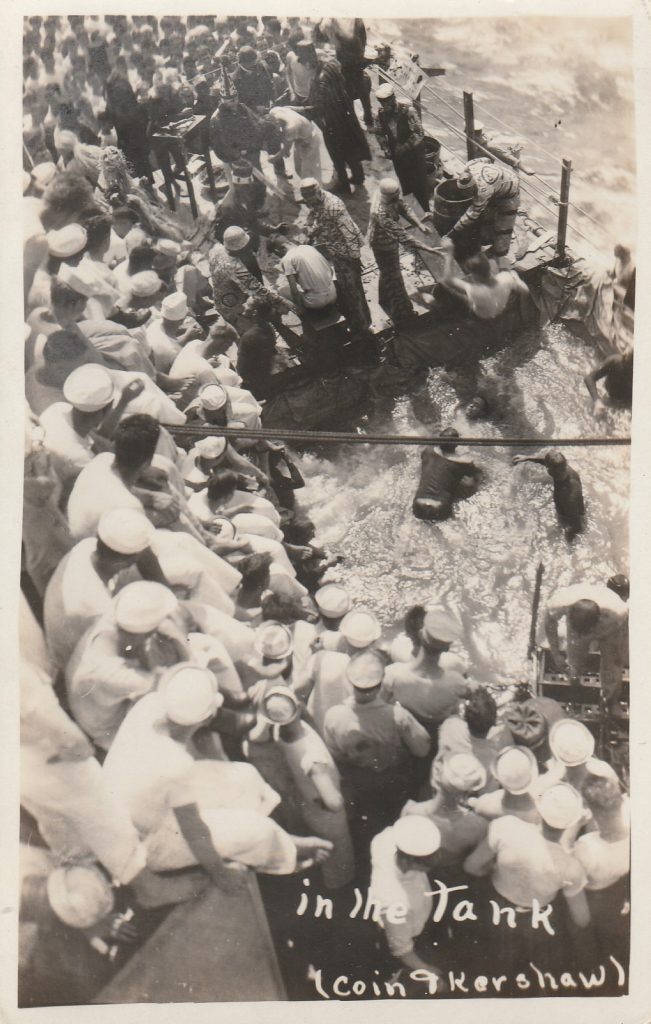

On its voyage from Hampton Roads to Rio De Janeiro, the Great White Fleet crossed the equator. To pay homage to King Neptune, the sailors who had not previously crossed from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern, had to go through a hazing ritual to make the transition from

pollywogs to

shellbacks. The conclusion being, each pollywog was dunked in a tank of seawater, set up on the deck that would cleanse them of any unseaworthiness they may have.

[There is no legend or lore as to how line crossings ceremonies began, but the tradition dates back at least 400 years. In early times the events could be quite brutal, so the origin depends entirely on what “King Neptune” knows!]

The three postcards above are from a 1920 goodwill voyage by the battleship USS Florida to Rio De Janeiro and depict this rite of passage. These postcards were probably printed in the battleship’s print shop and are part of a larger set of over twenty postcards.

A Last Look Back

A postcard of the SS United States passing the Chamberlin Hotel (upper left)

and Fort Monroe in June 1992. The great ocean liner was being towed to

Turkey for asbestos removal.

Chamberlin Hotel

New Chamberlin Hotel

The Chamberlin Hotel in the first postcard burned down in 1919 and the present building was built in the late 1920s. For many decades it was the premier hotel in Hampton Roads, offering a commanding view of Hampton Roads and the Chesapeake Bay. The Chamberlin is now a senior living community.

The USS Kansas painted gray after the voyage of the Great White Fleet. At the time, all the ships of the U.S. Navy were coal fired. The plume of black smoke not only coated the ships with coal-soot, but also gave away the ship’s position to enemy gunners. During World War I, the Navy began converting the fleet to oil. Also converted in the 1920s were the lattice masts. Tripods replaced the latticeworks. The postcard was published by the Souvenir Postcard Company and copyrighted by William B. Child of Newport, Rhode Island in 1910.

Equator-Crossings

The USS Kansas painted gray after the voyage of the Great White Fleet. At the time, all the ships of the U.S. Navy were coal fired. The plume of black smoke not only coated the ships with coal-soot, but also gave away the ship’s position to enemy gunners. During World War I, the Navy began converting the fleet to oil. Also converted in the 1920s were the lattice masts. Tripods replaced the latticeworks. The postcard was published by the Souvenir Postcard Company and copyrighted by William B. Child of Newport, Rhode Island in 1910.

Equator-Crossings

[A line crossing ceremony for a person who is sailing across the equator for the first time is a tradition in many national navies of the world, including the merchant marines and commercial freighters and tankers. Such events are also commonly “performed” for passengers on ocean liners and cruise ships.]

[A line crossing ceremony for a person who is sailing across the equator for the first time is a tradition in many national navies of the world, including the merchant marines and commercial freighters and tankers. Such events are also commonly “performed” for passengers on ocean liners and cruise ships.]

On its voyage from Hampton Roads to Rio De Janeiro, the Great White Fleet crossed the equator. To pay homage to King Neptune, the sailors who had not previously crossed from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern, had to go through a hazing ritual to make the transition from pollywogs to shellbacks. The conclusion being, each pollywog was dunked in a tank of seawater, set up on the deck that would cleanse them of any unseaworthiness they may have.

[There is no legend or lore as to how line crossings ceremonies began, but the tradition dates back at least 400 years. In early times the events could be quite brutal, so the origin depends entirely on what “King Neptune” knows!]

The three postcards above are from a 1920 goodwill voyage by the battleship USS Florida to Rio De Janeiro and depict this rite of passage. These postcards were probably printed in the battleship’s print shop and are part of a larger set of over twenty postcards.

A Last Look Back

On its voyage from Hampton Roads to Rio De Janeiro, the Great White Fleet crossed the equator. To pay homage to King Neptune, the sailors who had not previously crossed from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern, had to go through a hazing ritual to make the transition from pollywogs to shellbacks. The conclusion being, each pollywog was dunked in a tank of seawater, set up on the deck that would cleanse them of any unseaworthiness they may have.

[There is no legend or lore as to how line crossings ceremonies began, but the tradition dates back at least 400 years. In early times the events could be quite brutal, so the origin depends entirely on what “King Neptune” knows!]

The three postcards above are from a 1920 goodwill voyage by the battleship USS Florida to Rio De Janeiro and depict this rite of passage. These postcards were probably printed in the battleship’s print shop and are part of a larger set of over twenty postcards.

A Last Look Back

I noticed that the first card depicted refers to the hotel as the “Chamberlain”, as opposed to the correct “Chamberlin” spelling.

Of all the “sites” I have laid upon my table to visit through social media, this particular one that comes through my email is my favorite. Time and time again, educational and entertaining stories, cards and commentaries. I wonder how many others enjoy it as much? Many thanks to the administrator (s?) and those that take time to put together the wonderful articles. They enrich my life and help ease my distress over the seemingly endless cycle of depressing news. This particular article is a gem!

I have a my grandfathers post cards from the Great White Fleet, 1907-1908. He was a sailor on the USS Connecticut. About 100 + cards that had been mailed back home. Are they collectible? What are they worth in fair to good condition ?