George Miller

America’s Dream Highway

the Pennsylvania Turnpike

The lure of the open road, of driving on an endless ribbon of concrete into the setting sun with your windows down and the radio on, is a particularly powerful American fantasy. In a nation linked by interstates, freeways, thruways, expressways, and turnpikes such a fantasy is easy to fulfill. But in the days before eight-lane limited access, high-speed roads, such a thought must have been a dream. The first road in the United States to make that dream into a reality was the Pennsylvania Turnpike. When it opened in 1940, it offered to the American motorist a four-lane road without stop signs, or traffic lights, or intersections. No need to be caught behind slow-moving traffic, waiting for a clear stretch of road on which to pass. Here was a straight, flat ribbon of concrete, so safe that it didn’t have speed limits. “We had a new Mercury,” one early rider recalled, “and my brother had just gotten his driver’s license, and we drove a steady 90 miles per hour.” The American motorist had never seen such a road; so novel was it that on the day it opened motorists waited for hours for a chance to try America’s “dream” highway, to roar from one exit to the next and then back again.

The plan for a Pennsylvania turnpike was tied to several factors, none of which were dream related. Some were international: war clouds in Europe had created an awareness of the importance of roads as a means by which to move war materials and men. Some were domestic: the late 1930s was still a period of widespread unemployment and federally financed construction programs were a way of helping put America back to work. And some were purely pragmatic: a long-abandoned rail route of the South Penn Railroad offered a convenient foundation upon which to build the new highway.

The South Penn was first incorporated in 1854 as “The Duncannon, Landisburg & Broad Top Railroad” and survived various planned route and name changes until 1863 when it officially became the “South Pennsylvania Railroad Company.” The plan was to construct a railroad across the southern part of Pennsylvania to compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad which ran a middle route through the state.

For more than 20 years parts of different construction projects continued, but work ended in 1885 and in the years afterward the old South Penn right-of-way lay abandoned. The tunnels filled with water and the graded railway was covered with underbrush. Various plans to use the road were advanced over the years, but it was not until 1935 that the idea of building an east-west express highway across Pennsylvania on the old South Penn line caught on.

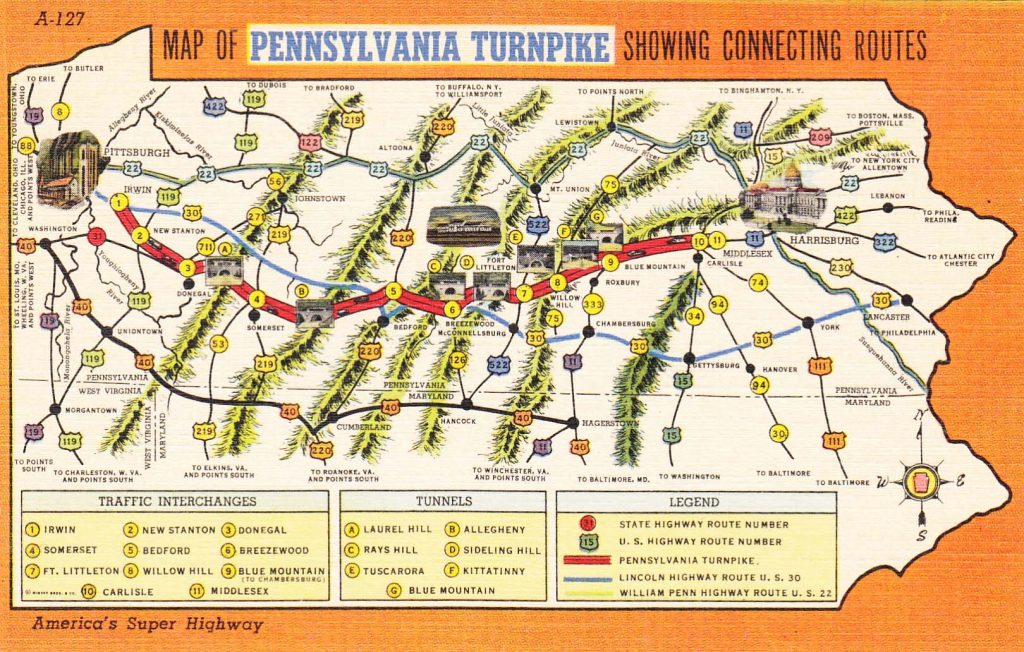

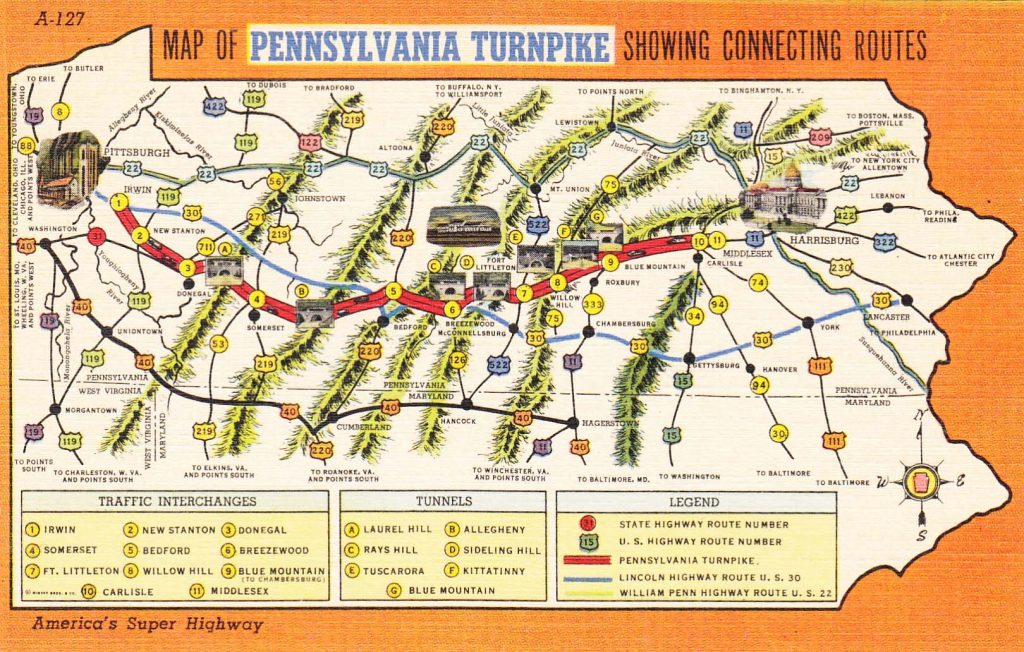

This linen map shows the two competing toll-free roads: Routes 30 and 22.

At the time there were already two toll-free roads which crossed the state: the Lincoln Highway (U.S. Route 30) and the William Penn Highway (P.A. Route 22). Both roads had severe limitations. The Lincoln Highway climbed over Pennsylvania’s mountains at steep grades; the William Penn Highway involved less mountainous terrain, but it offered a far from direct path across the state. If a new, more southern route could be built, driving time across the state could be substantially reduced.

Preliminary work on the proposed road began in January 1936 and when the initial surveys proved promising, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission was created in 1937 and authorized to build a four-lane toll highway.

The first contract was awarded on October 26, 1938, and when all the phases of construction had been let out to contractors, there was a total of 155 firms from 18 states, employing a peak number of 18,000 workmen, engaged in building the new road. Time was crucial since the federal agencies funding the project had stipulated that it had to be “substantially” completed by June 29, 1940. To meet the deadlines contractors regularly worked two eight-hour shifts a day and, on occasion, work continued unbroken through three shifts. Twenty-three months later, on October 1, 1940, the turnpike was officially open to traffic.

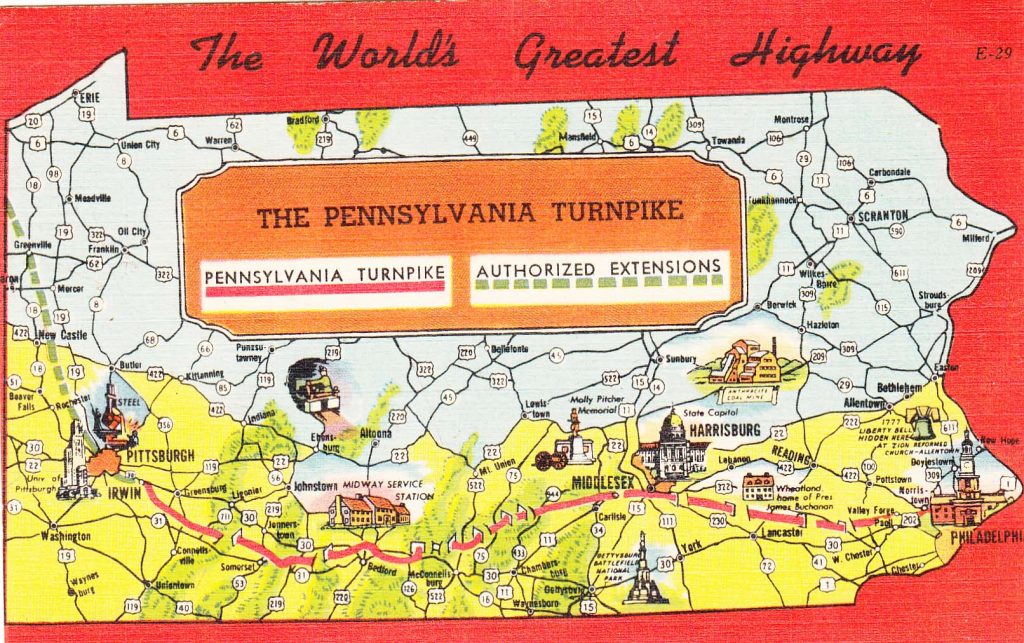

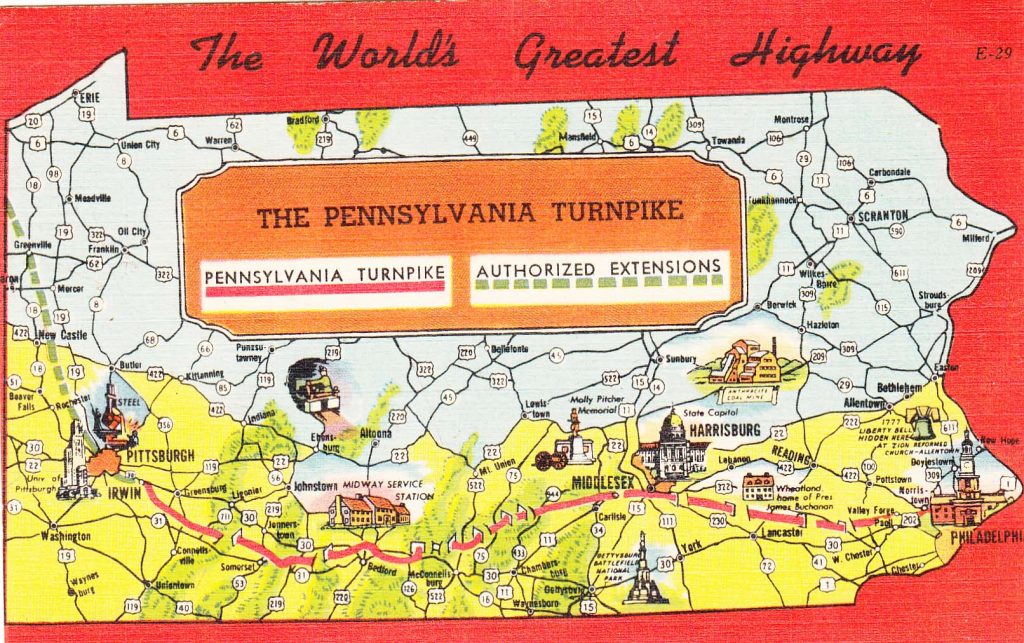

The Turnpike has been completed to Valley Forge,

hence the card dates from 1950.

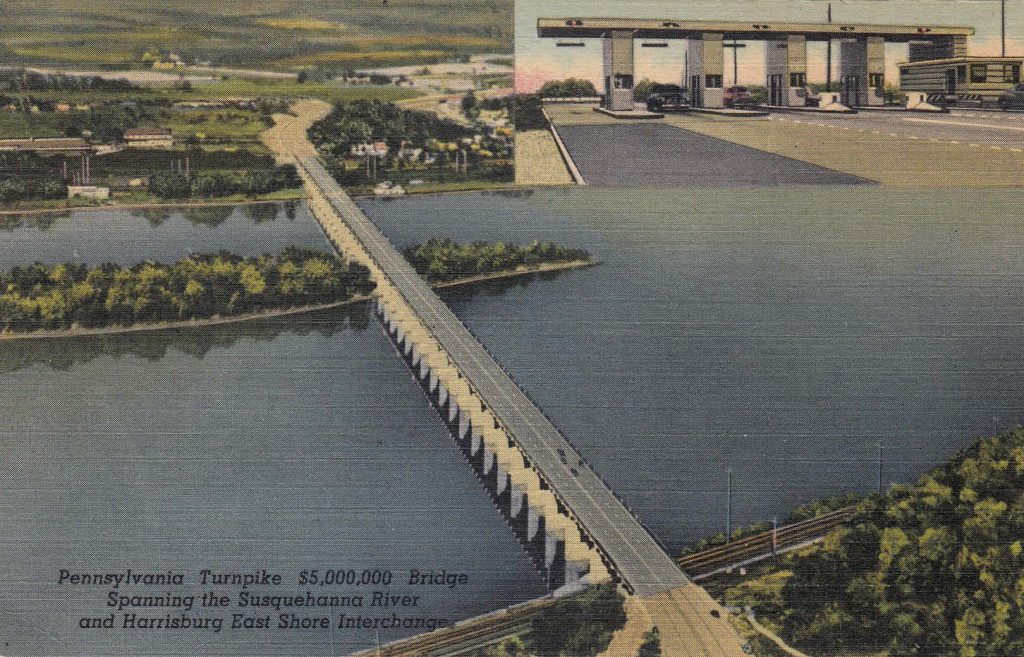

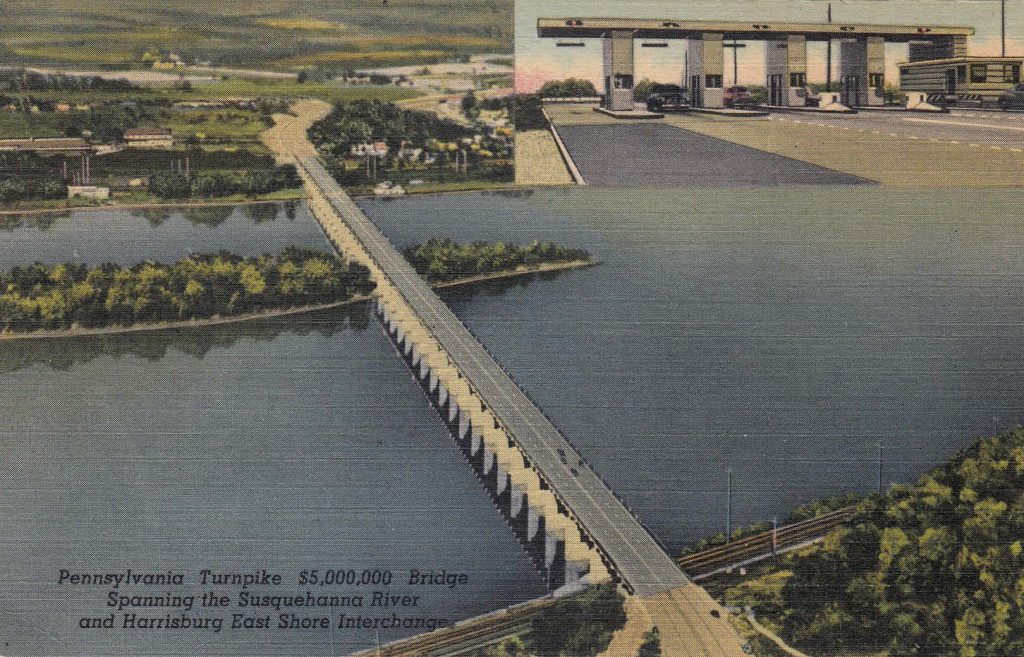

Probably dating from 1950 since the Harrisburg bridge

was part of the first Philadelphia Extension.

From the first, the intention was to build a “super,” “safe,” “all weather” road. To speed traffic, the turnpike was to have a maximum ascending grade of 3% (a three-foot rise for every 100 feet of length). The lower grades meant faster moving traffic and less hazardous winter driving conditions. The flatter roadway was achieved through the use of fill and tunnels.

Not only was the new Turnpike flatter than any other roads in Pennsylvania, it was also straighter. Three-fourths of the original 160 miles were completely free from curves. As a result, the average travel time between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh was cut from six hours to less than three.

When it opened, the Turnpike had no speed limit for automobiles. Since the road was free from the more obvious hazards of driving – intersections, pedestrians, two-lane traffic – the assumption was that accidents would essentially be eliminated. This did not prove to be the case. Highway hypnosis, a new phenomenon, took its toll as did mechanical failure (particularly tires) and driver error. By the spring of 1941 a speed limit of 70 mph was in place. The engineers discovered as well that steel median guardrails had to be installed between the two strips of roadway.

There had been a considerable debate over the feasibility of a toll road in an area where toll-free roads already existed. To travel the entire length of the original pike, automobiles paid $1.50. Shorter distances cost approximately one cent per mile. Because of the costs, the daily traffic had originally been estimated at 750 vehicles; the actual figure two weeks after the pike opened was 26,000 vehicles. Aside from offering an unrestricted and totally new driving experience, the Turnpike represented a substantial savings to truckers through reduced travel time, reduced maintenance, and reduced insurance costs.

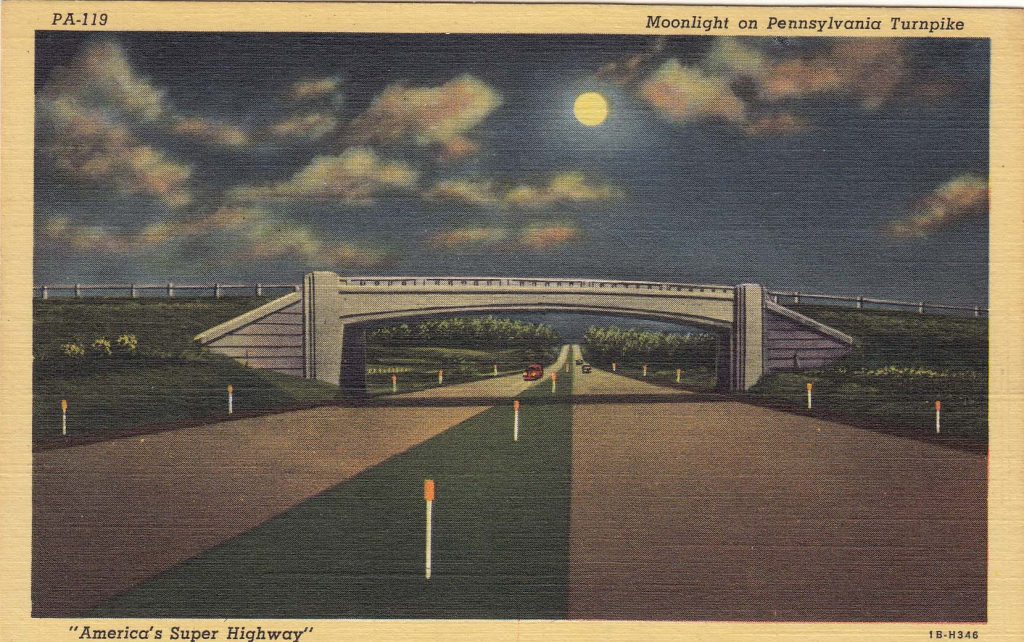

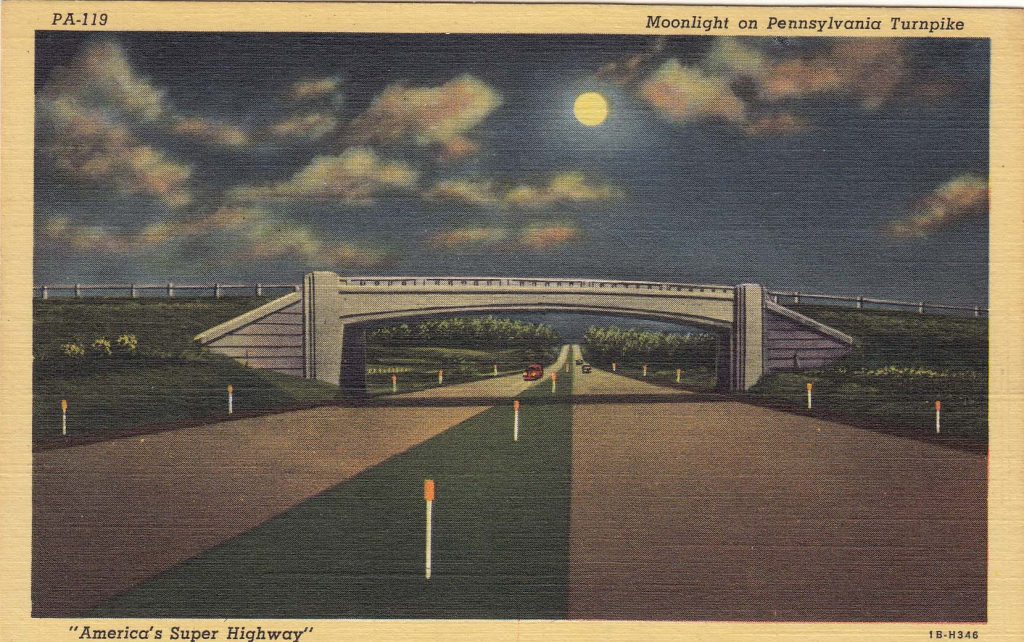

Moonlight on Pennsylvania Turnpike

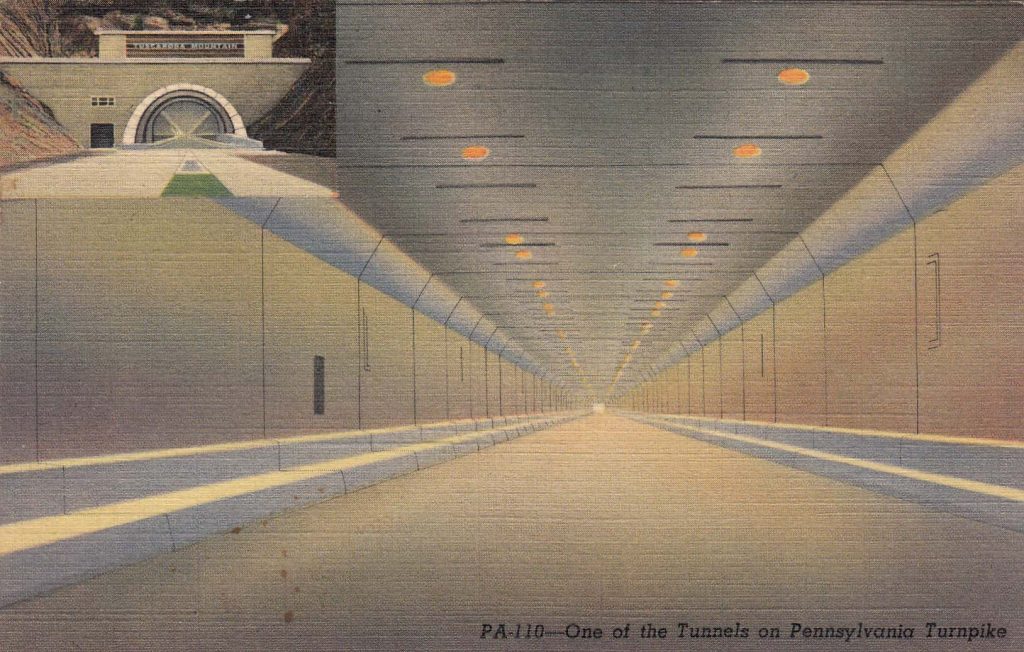

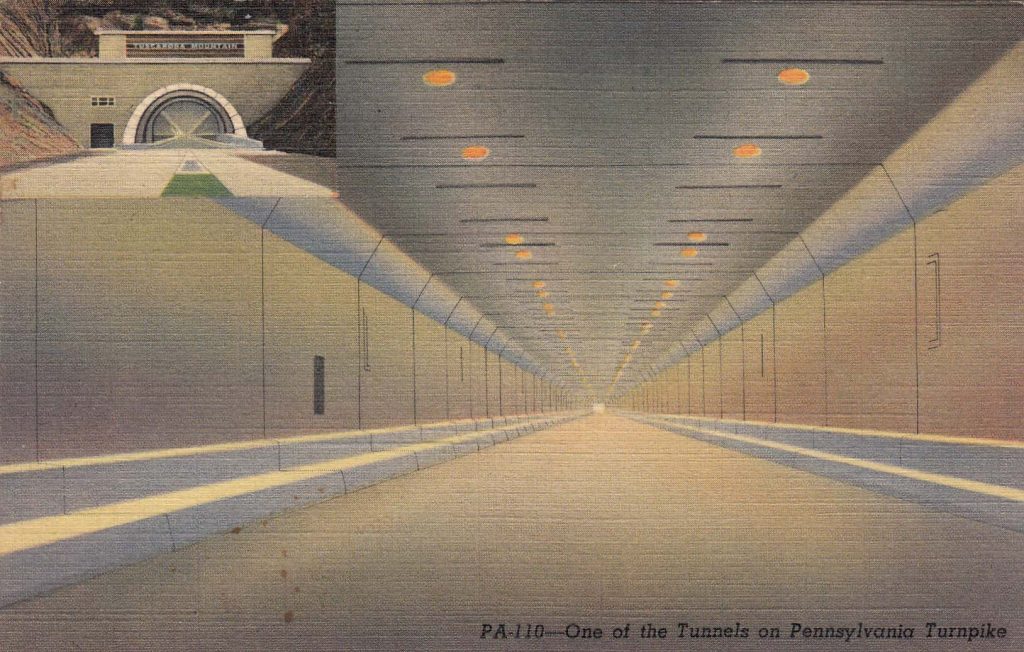

Interior of the Allegheny Tunnel near New Baltimore.

Even before the original section of the Turnpike was open, plans were being made to extend the road to Philadelphia. That link came in two parts: the Philadelphia Extension, running from Carlisle to Valley Forge, opened in 1950; the Delaware River Extension, running from Valley Forge to the New Jersey border, opened in 1954, although the final bridge link between the Pennsylvania and New Jersey turnpikes was not completed until 1956. The Western Extension, from Irwin to the Ohio state border, opened in 1951. The final section of the 470-mile toll road came in 1957 when the 110-mile Northeast Extension opened.

Turnpike traffic volume grew rapidly over the years. During its first year, nearly 2.5 million cars and trucks travelled the road. By 1960, the total had reached 31.7 million.

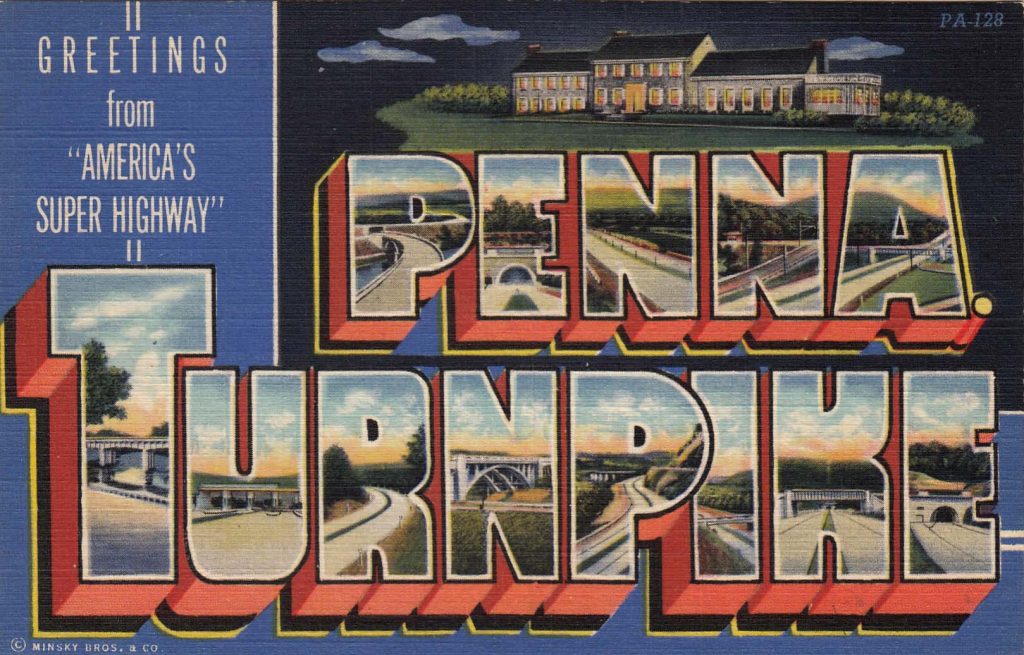

The length of America’s “dream,” “super” highway was soon captured on postcards. Despite the engineering marvel that it was, few cards of the actual construction were made. The only known group of real photocards are ones made by Clyde A. Laughlin, a local photographer and postcard publisher in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. The real “magic” of the turnpike was captured on linen postcards. The largest single printer of such cards was Curt Teich of Chicago. Another major printer of turnpike linens was Tichnor Bros., Inc., Boston.

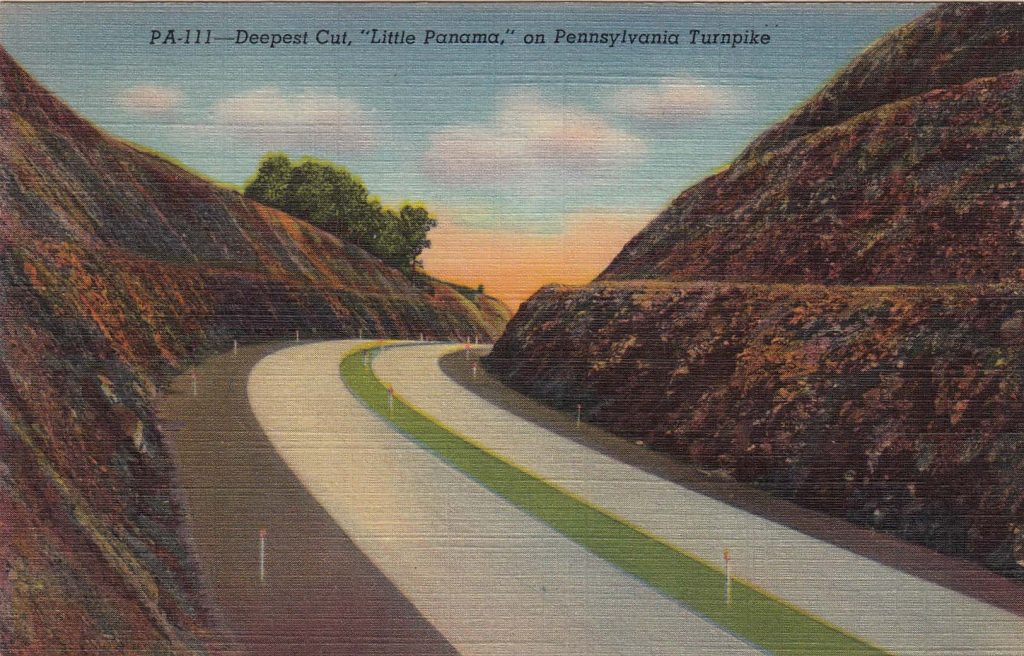

The linen postcard in its composition and printing always offered a romanticized and idealized view of-its subject. Unlike the cards of the “golden-age,” the linen view did not capture realistic detail. The hard, sharp reality of the black and white view was replaced by smooth, clean, softly colored surfaces. It was better than reality and could make even a road seem romantic.

A favorite among the linen cards is the moonlight scene. As a full moon bathes the roadway in its soft light, the road surface is unbroken, unmarred by painted stripes or guard rails. The cards of the tunnel interiors are antiseptically clean; even futuristic as visions in concrete recede into a vanishing point.

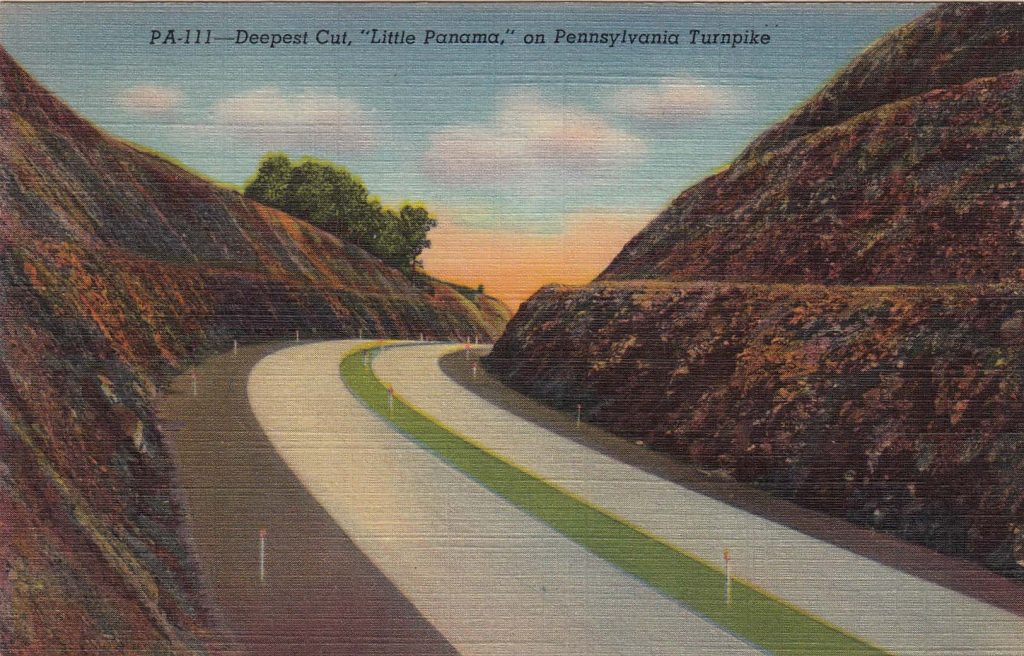

Even a “cut” in a mountain could seem magical as the roadway, separated by a perfectly grass-green strip, gracefully bends between two glistening banks of rock toward some unknown destination which glows in a golden orange.

As highways go, the Pennsylvania Turnpike still has its moments. If you plan to drive across Pennsylvania, the lore of the open road can be quite enticing. If the weather is nice, open your windows, set your cruise control, turn your radio up to loud and enjoy the view as you drive into the setting sun. But be careful, don’t let a speeding ticket ruin your “dream” ride.

The lure of the open road, of driving on an endless ribbon of concrete into the setting sun with your windows down and the radio on, is a particularly powerful American fantasy. In a nation linked by interstates, freeways, thruways, expressways, and turnpikes such a fantasy is easy to fulfill. But in the days before eight-lane limited access, high-speed roads, such a thought must have been a dream. The first road in the United States to make that dream into a reality was the Pennsylvania Turnpike. When it opened in 1940, it offered to the American motorist a four-lane road without stop signs, or traffic lights, or intersections. No need to be caught behind slow-moving traffic, waiting for a clear stretch of road on which to pass. Here was a straight, flat ribbon of concrete, so safe that it didn’t have speed limits. “We had a new Mercury,” one early rider recalled, “and my brother had just gotten his driver’s license, and we drove a steady 90 miles per hour.” The American motorist had never seen such a road; so novel was it that on the day it opened motorists waited for hours for a chance to try America’s “dream” highway, to roar from one exit to the next and then back again.

The plan for a Pennsylvania turnpike was tied to several factors, none of which were dream related. Some were international: war clouds in Europe had created an awareness of the importance of roads as a means by which to move war materials and men. Some were domestic: the late 1930s was still a period of widespread unemployment and federally financed construction programs were a way of helping put America back to work. And some were purely pragmatic: a long-abandoned rail route of the South Penn Railroad offered a convenient foundation upon which to build the new highway.

The South Penn was first incorporated in 1854 as “The Duncannon, Landisburg & Broad Top Railroad” and survived various planned route and name changes until 1863 when it officially became the “South Pennsylvania Railroad Company.” The plan was to construct a railroad across the southern part of Pennsylvania to compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad which ran a middle route through the state.

For more than 20 years parts of different construction projects continued, but work ended in 1885 and in the years afterward the old South Penn right-of-way lay abandoned. The tunnels filled with water and the graded railway was covered with underbrush. Various plans to use the road were advanced over the years, but it was not until 1935 that the idea of building an east-west express highway across Pennsylvania on the old South Penn line caught on.

The lure of the open road, of driving on an endless ribbon of concrete into the setting sun with your windows down and the radio on, is a particularly powerful American fantasy. In a nation linked by interstates, freeways, thruways, expressways, and turnpikes such a fantasy is easy to fulfill. But in the days before eight-lane limited access, high-speed roads, such a thought must have been a dream. The first road in the United States to make that dream into a reality was the Pennsylvania Turnpike. When it opened in 1940, it offered to the American motorist a four-lane road without stop signs, or traffic lights, or intersections. No need to be caught behind slow-moving traffic, waiting for a clear stretch of road on which to pass. Here was a straight, flat ribbon of concrete, so safe that it didn’t have speed limits. “We had a new Mercury,” one early rider recalled, “and my brother had just gotten his driver’s license, and we drove a steady 90 miles per hour.” The American motorist had never seen such a road; so novel was it that on the day it opened motorists waited for hours for a chance to try America’s “dream” highway, to roar from one exit to the next and then back again.

The plan for a Pennsylvania turnpike was tied to several factors, none of which were dream related. Some were international: war clouds in Europe had created an awareness of the importance of roads as a means by which to move war materials and men. Some were domestic: the late 1930s was still a period of widespread unemployment and federally financed construction programs were a way of helping put America back to work. And some were purely pragmatic: a long-abandoned rail route of the South Penn Railroad offered a convenient foundation upon which to build the new highway.

The South Penn was first incorporated in 1854 as “The Duncannon, Landisburg & Broad Top Railroad” and survived various planned route and name changes until 1863 when it officially became the “South Pennsylvania Railroad Company.” The plan was to construct a railroad across the southern part of Pennsylvania to compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad which ran a middle route through the state.

For more than 20 years parts of different construction projects continued, but work ended in 1885 and in the years afterward the old South Penn right-of-way lay abandoned. The tunnels filled with water and the graded railway was covered with underbrush. Various plans to use the road were advanced over the years, but it was not until 1935 that the idea of building an east-west express highway across Pennsylvania on the old South Penn line caught on.

Even a “cut” in a mountain could seem magical as the roadway, separated by a perfectly grass-green strip, gracefully bends between two glistening banks of rock toward some unknown destination which glows in a golden orange.

As highways go, the Pennsylvania Turnpike still has its moments. If you plan to drive across Pennsylvania, the lore of the open road can be quite enticing. If the weather is nice, open your windows, set your cruise control, turn your radio up to loud and enjoy the view as you drive into the setting sun. But be careful, don’t let a speeding ticket ruin your “dream” ride.

Even a “cut” in a mountain could seem magical as the roadway, separated by a perfectly grass-green strip, gracefully bends between two glistening banks of rock toward some unknown destination which glows in a golden orange.

As highways go, the Pennsylvania Turnpike still has its moments. If you plan to drive across Pennsylvania, the lore of the open road can be quite enticing. If the weather is nice, open your windows, set your cruise control, turn your radio up to loud and enjoy the view as you drive into the setting sun. But be careful, don’t let a speeding ticket ruin your “dream” ride.

One of the factors driving the completion date was the 1940 election. President Roosevelt had approved a grant of $24 million dollars from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to fund the construction. In addition, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) loaned $32 million dollars to be repaid by toll revenue. Roosevelt saw the turnpike as another feather in his cap. It put a number of men to work building the road and manufacturing construction materials. The Pennsylvania Turnpike spurred the construction of the New Jersey and Massachusetts Turnpikes after WW II and served as a model for the Interstate Highway System… Read more »

One of the most interesting features of the Pennsylvania Turnpike was the fact that the tunnel which connects the Midway South and Midway North service plazas was accessible to travelers until the mid-sixties. The tunnel is now used for storage.