George Miller

That Old Time Religion

The period from 1870 to 1918 in the United States was marked by a nationwide concern for the values and forms of the “old-time” religion. The increasing urbanization of America, the increasing secularization of its society, the massive influx of Catholic and Jewish immigrants — all served to erode Protestantism. In the hopes of re-awakening and revitalizing the Protestant religion in America, the country turned to the evangelist. By 1911 there were 650 professional evangelists in the U.S. and over 1300 part-time revivalists. America’s religious re-awakening is chronicled on postcards — cards of evangelists and their families, cards advertising “campaigns,” cards of evangelists in action.

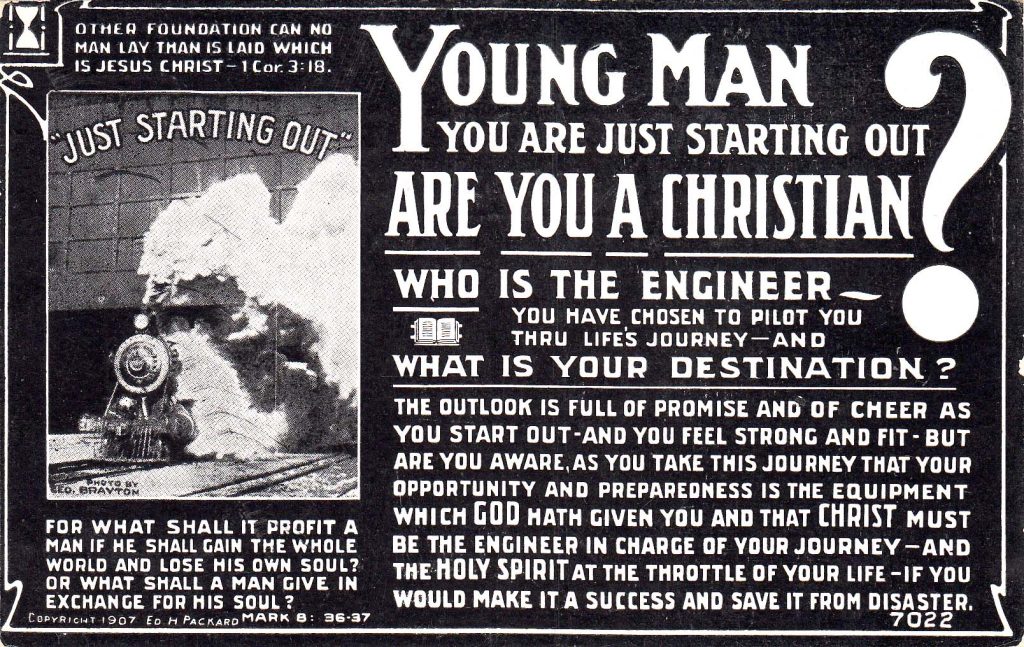

The modern evangelistic campaign, in its techniques and organization, owes much to Dwight L. Moody. Born in Northfield, Massachusetts, in 1837, Moody moved to Chicago at age 19 to sell shoes and to make a $100,000, his greatest ambition. A tireless Sunday-school recruiter and Y.M.C.A. worker, Moody opened his own interdenomminational North Market Sabbath School, often personally gathering his flock from the Chicago slums. In 1861, Moody gave up his thriving business to devote himself totally to religious work, asking of everyone he met his distinctive question: “Are you a Christian?” In 1864 he founded the Illinois Street Church, known later as Moody Church — the forerunner of the independent fundamentalist tabernacles and storefront churches now so common.

The direction of Moody’s life changed sharply in 1870 when he teamed up with Ira D. Sankey, a young and talented hymn singer. Moody and Sankey began their evangelistic campaign not in Chicago, but in Scotland and England in 1873 to 1875. English audiences flocked to hear them and by the time they sailed for home in July 1875, some three to four million Scots and Brits had attended their services.

The extraordinary success of the campaigns was in large part related to the mixture of music and sermon. Moody himself said, “The people come to hear Sankey sing and then I catch them in the gospel net.” Sankey’s particular talent lay in ha solo baritone performances of hymns that he and his associates wrote. Many reduced the audience to tears: songs like The Ninety and Nine, a story of the one lost sheep Christ brought home to the fold; or Room Among the Angels, a story of dying young Mary, whose mother had once cruelly struck her for being in the way – who asks, “Mother…up among the happy angels, is there room for Mary there?”

Moody was a powerful and emotional speaker. He kept his messages short, his theology simple, and his language vivid and colloquial. A typical Moody sermon included biblical stories modernized in often almost irreverent ways, and sentimental stories about death, sickness, the evils of the world, the wonders wrought by conversions. Moody was a compelling storyteller who could easily bring his audience to tears. He was accused of being a “salesman” for God. He was but he was proud of it. Moody knew the effectiveness of salesmanship, efficient business methods, and advertising. Every successful evangelist after Moody copied his methods and organizational strategies.

After their return from England, Moody and Sankey toured the U.S., beginning in Brooklyn, moving then to a Pennsylvania Railroad freight warehouse in Philadelphia, then to a long series of other cities. Between 1880 and 1890 Moody organized conferences in Northfield, Massachusetts, and founded the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. He died in 1899 at the very beginning of the postcard era in America. Moody’s message, though, was captured on cards published by the Gospel Publicity League.

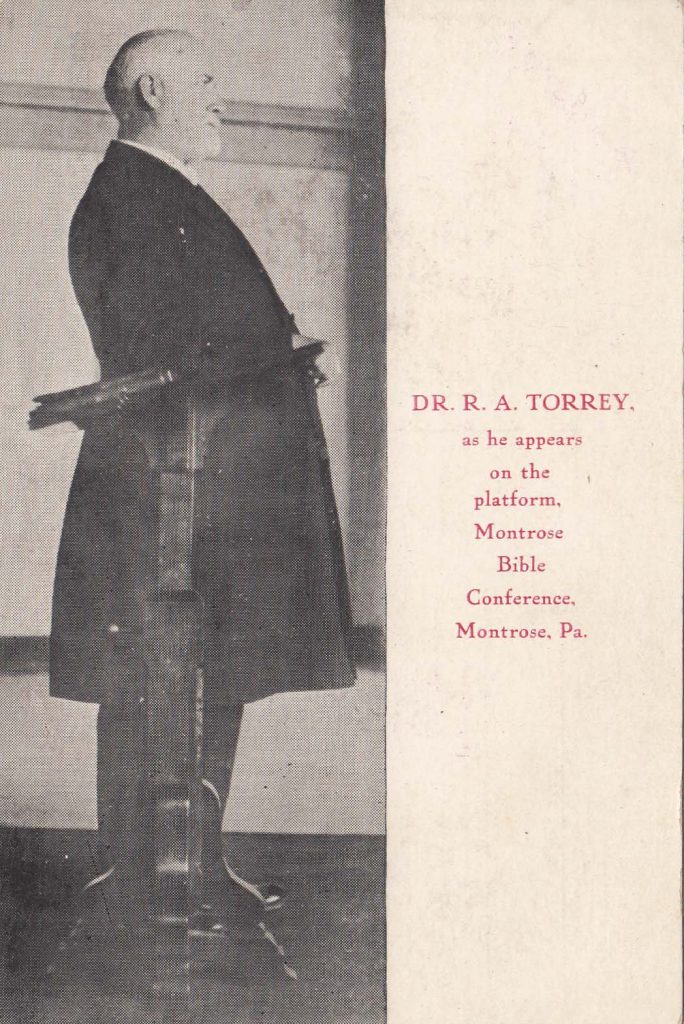

Reuben A. Torrey was the first superintendent of the Moody Bible Institute and, unlike many evangelists, the product of formal divinity school training — at Yale. His musical partner on the campaign circuit was Charles Alexander, a graduate of the Moody Institute. Unlike Sankey, to whom he was often compared, Alexander was more truly an emcee who specialized in “warming up” audiences, telling jokes, staging singing competitions among sections of the audience, before Torrey appeared. Their most successful campaign was in Philadelphia in the spring of 1906; it lasted sixty-two days and cost only $38,365. That revival produced 7,000 converts.

The partnership between Alexander and Torrey dissolved in 1908 when Alexander joined with John Wilbur Chapman, who had previously worked with B. Fay Mills, a popular evangelist in the 1890s. Chapman popularized the “simultaneous evangelism” plan for conquering big cities. In Boston in 1909, Chapman divided the city into twenty-seven districts. Each district had its own evangelist and singer who conducted services in a district hall. Meanwhile, Chapman and Alexander held forth at central meetings in Tremont Temple. Total attendance for the three-week campaign was slightly over three-quarters of a million.

One of Chapman’s assistants was William Ashley (“Billy”) Sunday, who in 1891 had quit baseball for religious work. Billy Sunday was a crowd-pleaser. He dramatized everything. He acted out stories, he ran, he slid, he did handsprings, he shouted, he pounded the pulpit, he smashed chairs. One newspaper headline in 1904 read, “Evangelist Does Great Vaudeville Stunts in Tabernacle Pulpit.” For Billy, saving souls would reform society. By 1901 he advertised his revivals as “civic clean-ups” and moral reform movements. He attacked dancing, card playing theatergoing, prostitution, and most especially “the damnable liquor traffic.” In 1910 Billy was joined by Homer Alvin Rodeheaver, his trombone-playing emcee.

And Billy was successful. During his forty-year career, Billy held almost 300 revivals. In his twenty most successful revivals, nearly 600,000 persons came forward. He claimed that in the days before radio, he preached to 100 million people and converted a million of them.

The appeal of an evangelist was related to several factors. First, he appealed to the people. The religion he preached was simple and its message accessible to an audience who wanted to believe in the “old-time” values of hard work and moral rectitude. Secondly, he was supported by the establishment. Businessmen, men such as John Wanamaker, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., S. S. Kresge, Henry Clay Frick, were important supporters of the major evangelists. Religion was good for the working man. It kept him out of the saloon, and it encouraged good work habits. Thirdly the Protestant churches, particularly the city churches, needed the evangelist to help boost sagging memberships.

The coming of radio created a new breed of evangelists, best exemplified in Aimee Semple McPherson. Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1890, Aimee Kennedy, an only child, was dedicated by her mother to God’s service. Distracted by typical adolescent “doubts,” at seventeen Aimee attended a revival led by Robert James Semple and subsequently “surrendered her life to Christ.” Shortly thereafter the six-foot, fair-haired, blue-eyed Semple asked her to marry and accompany him as a missionary to China. They had been in Hong Kong only three months when Semple died of malaria. A month later Aimee gave birth to her first child, Roberta Star Semple.

Aimee and her six-month old daughter returned home and after a few quiet years Aimee married Harold Stewart McPherson. Plagued by ill health, which she interpreted as a sign of God’s chastisement of her for abandoning her evangelism, Aimee rededicated her life to God and returned to religious work. She began her ministry in August 1915 as Sister McPherson. With her husband she traveled up and down the eastern seaboard in her “Gospel Auto.” In 1918 when McPherson ceased working with her, she was joined by her mother. Together they headed for Los Angeles, driving all day and camping at night by the roadside with her two children Roberta and Rolf.

Between 1918 and 1923 she crossed the country eight times holding revivals in cities such as Philadelphia, San Francisco, Baltimore, Washington, Denver, and St. Louis. In San Francisco in April 1922 she gave the first sermon broadcast by radio. In that same year she proclaimed her “Four Square Gospel,” the term derived from the Book of Ezekiel and used by Sister Aimee to refer to the four-fold ministry of Jesus.

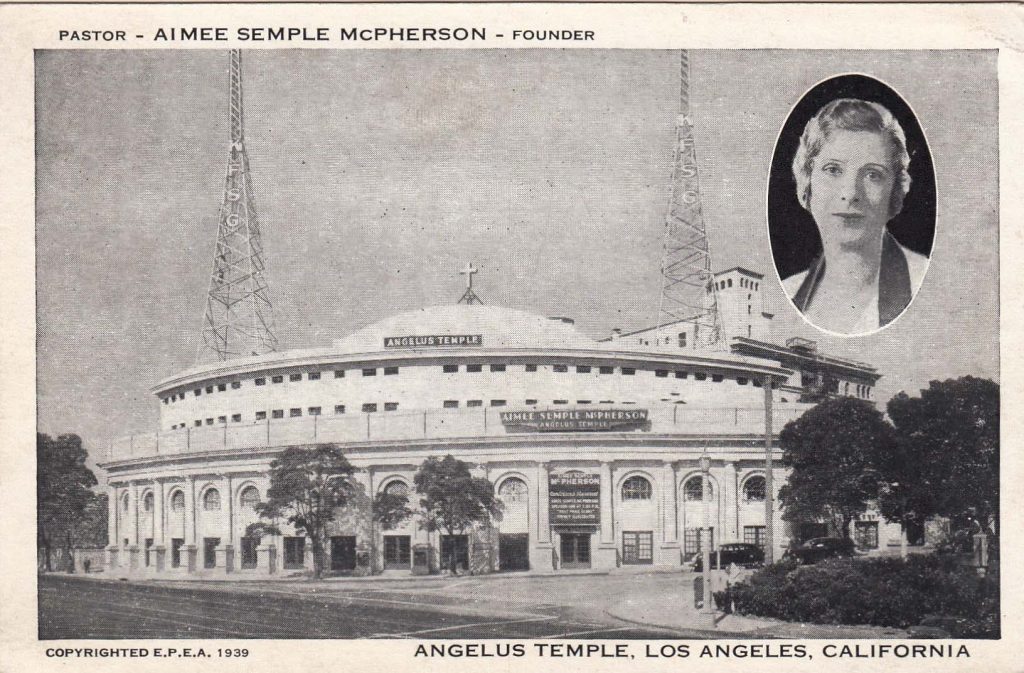

Unlike many evangelists before her, Sister Aimee erected a permanent home for her church — Angelus Temple, near Echo Park in Los Angeles, begun in 1921 and dedicated in 1924. In February 1924 she broadcast her first message over her own radio station KFSG (“Kall Four Square Gospel”).

She became front-page headlines, however, on May 18, 1926, when she mysteriously disappeared while swimming in the Pacific Ocean. Thousands of her faithful kept a vigil on Ocean Park beach. Despite some questionably authentic ransom notes, Mother Kennedy insisted that her daughter was dead and a memorial service, attended by some 17,000 mourners, was held at Angelus Temple. A month later, though, Aimee turned up in Arizona telling a story of her kidnapping and escape. Not everyone believed Aimee. Indeed, she became the focus of a grand jury investigation which lasted for 88 days. In the end, Aimee won and returned to her ministry. She died of a heart attack at age 53 in September 1944.

Despite the success of evangelists such as Sister Aimee, the era of the big city revival and the nationally known revivalist passed with the outbreak of World War One and the Depression. The re-awakening was over.

The song “Hooray for Hollywood” contains the lyric “Where anyone at all from Shirley Temple to Aimee Semple/ Is equally understood.” In “Chicago”, the titular city is described as “[t]he town that Billy Sunday couldn’t shut down”.

It is interesting to know about the reason behind a building I remember seeing many years ago and the lady conncted with it. I lived in Glendale CA with my parents & a maternal Grandma who had a husband who died when Mom was a teen. He was part of printing history having been a very early lithographer.in LA and having photographed Yosemite before 1906.