Participation in the Great War changed everything on Broadway. Musicals grew more nationalistic, and the operetta era was running its course. Drama became more introspective and socially engaged as Broadway searched for an authentically American theater. New challenges burst on the horizon. Vaudeville was considered low-brow though popular. It was never a tough competitor to legitimate theater even though its style and verve were highly influential. Above all, the theatrical audience was suddenly drawn away by the increasing sophistication of films especially after talkies emerged during the 1930s.

The theater-building marathon north of 42nd Street continued unabated until the mid 1920s.

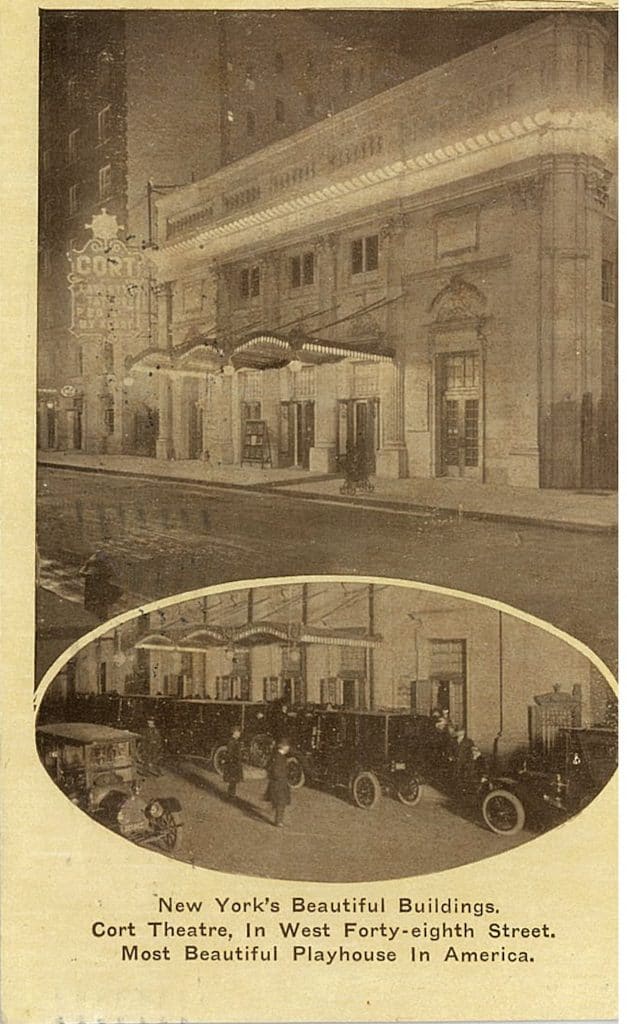

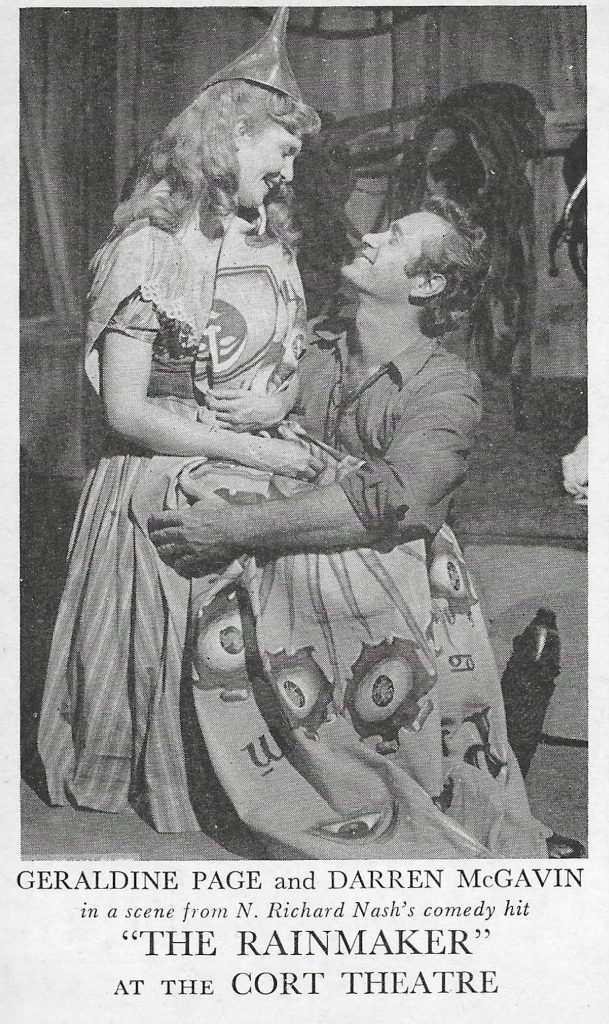

The Cort Theatre, recently renamed the James Earl Jones Theatre was built for impresario John Cort in the neoclassical style in 1912, designed by theatrical master architect Thomas Lamb. A modestly sized structure with 1092 seats across three levels, the Shubert-owned property is located at 138 West 48th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues. The Cort has always been known as a “lucky” theater for its propensity to turn doubtful shows into successes. When the new theater of realism began to infiltrate Broadway, the Cort became the showcase for long running hits. The Theater Guild for example returned to the Cort in the 1950s, producing comedies like “The Rainmaker.”

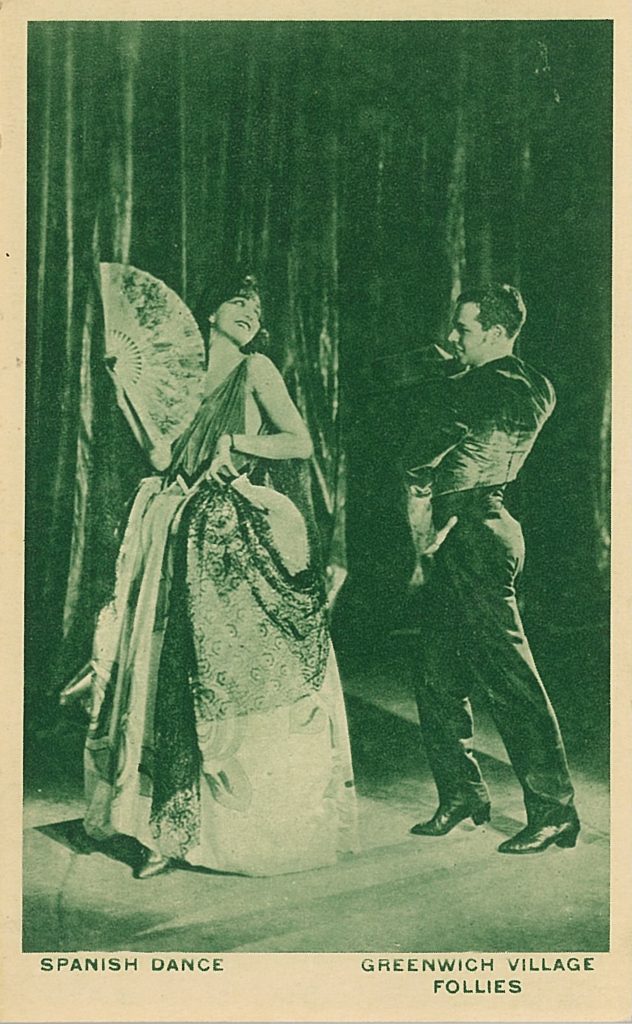

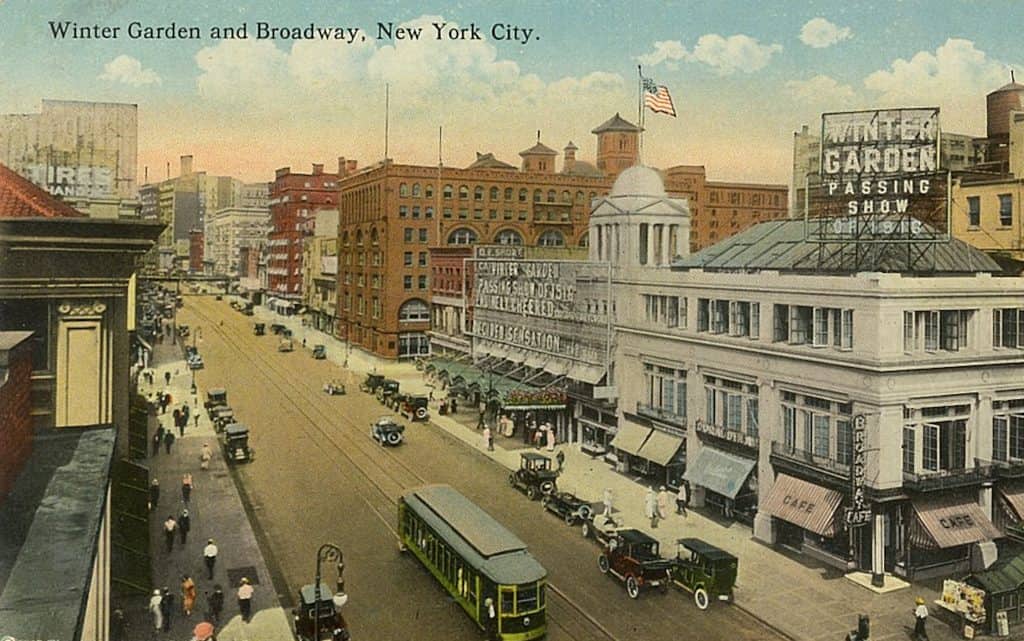

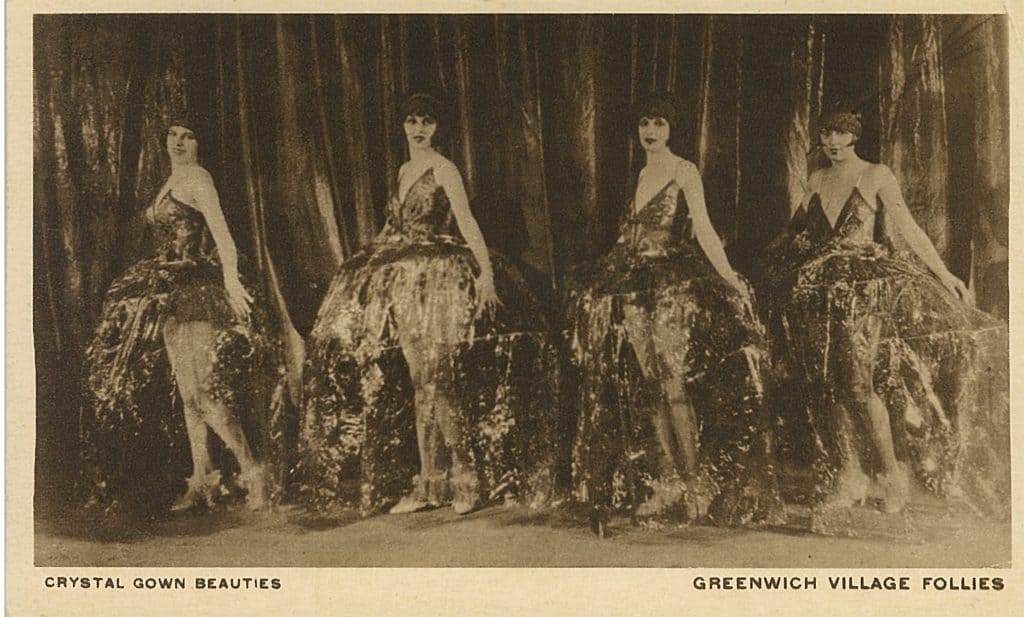

The Winter Garden Theatre takes up the major share of an oddly shaped block in the northern end of the theater district between Broadway and 7th Avenue and 50th and 51st Streets. It has been there since 1911 in a design by William Albert Swasey that replaced the National Horse Exchange at that site and an earlier incarnation of the Winter Garden located downtown at Bond Street. The current configuration dates to 1922 when the building was completely redesigned by architect Herbert J. Krapp for the Shubert Organization that was seeking a slightly larger theater. In its early days the site was known for hosting shows like the Greenwich Village Follies, influenced by the revues pioneered by Florenz Ziegfeld which featured original scores, comedy routines, and an abundance of beautiful women.

The Winter Garden arrived at a moment when two diverse trends were trying to supplant the operetta explosion which had run its course – serious engaged realism then bursting out of the creative cauldron of Greenwich Village and the unserious sensuous “revue” trend that had grown out of vaudeville, burlesque, and the chorus lines of Edwardian musical comedies. The Winter Garden Theatre was known through the years for long-running hit shows. Contemporary audiences recall the venue as the place where they saw Cats and, or Mamma Mia, which were the only productions running here from 1982 to 2013.

Devotees of serious legitimate theater who were disappointed by the operetta trend took some steps to better compete. Unfortunately, their principal effort misdiagnosed the problem and misdirected the solution. They wished for something like a “national theater” that could become an arbiter of theatrical quality. Like elitists everywhere, they expected that appealing to wealthy attendees with amenities like plush box seats and employing screening committees for quality control would guarantee solvency better than having producers chase after popular tastes.

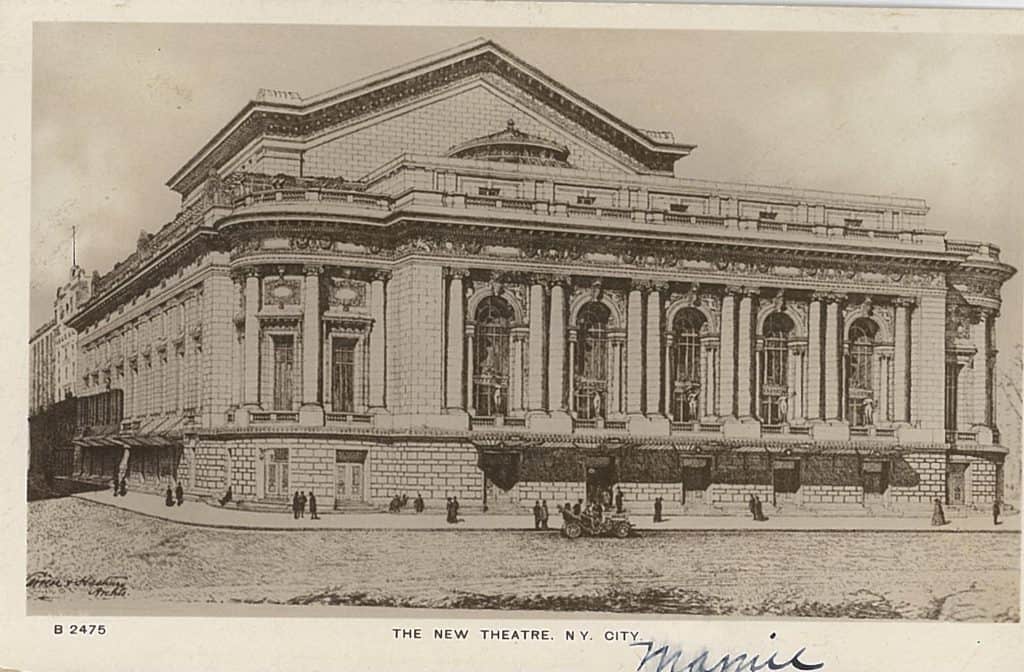

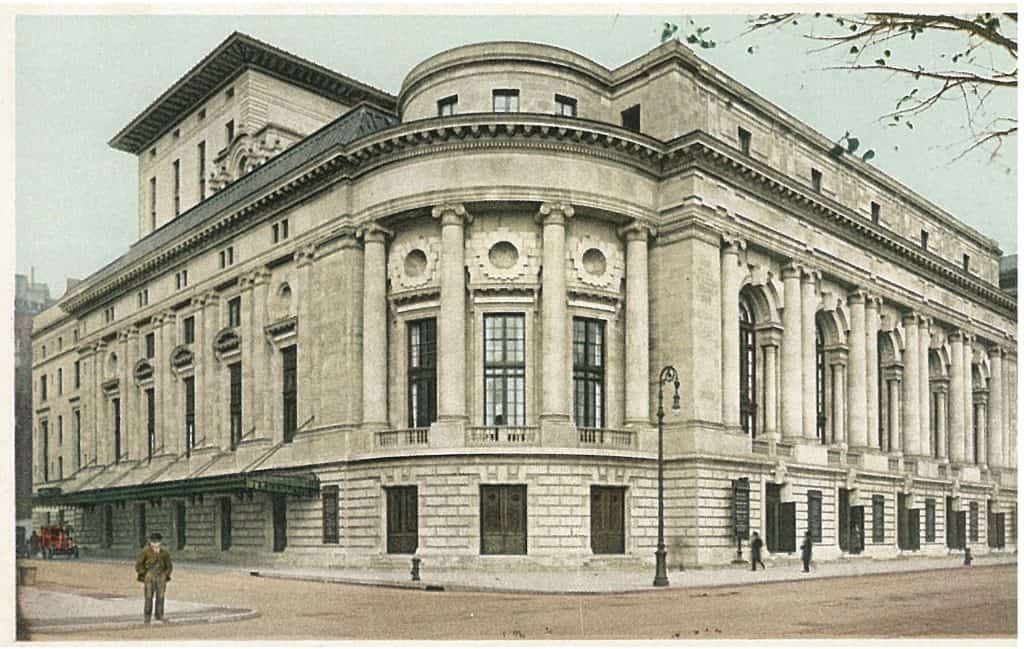

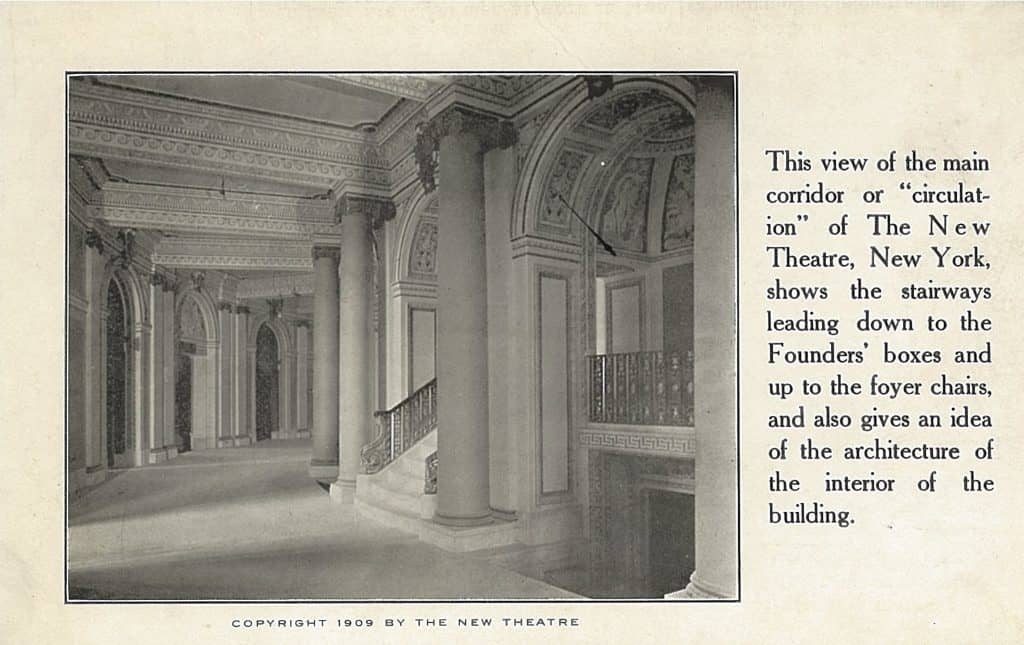

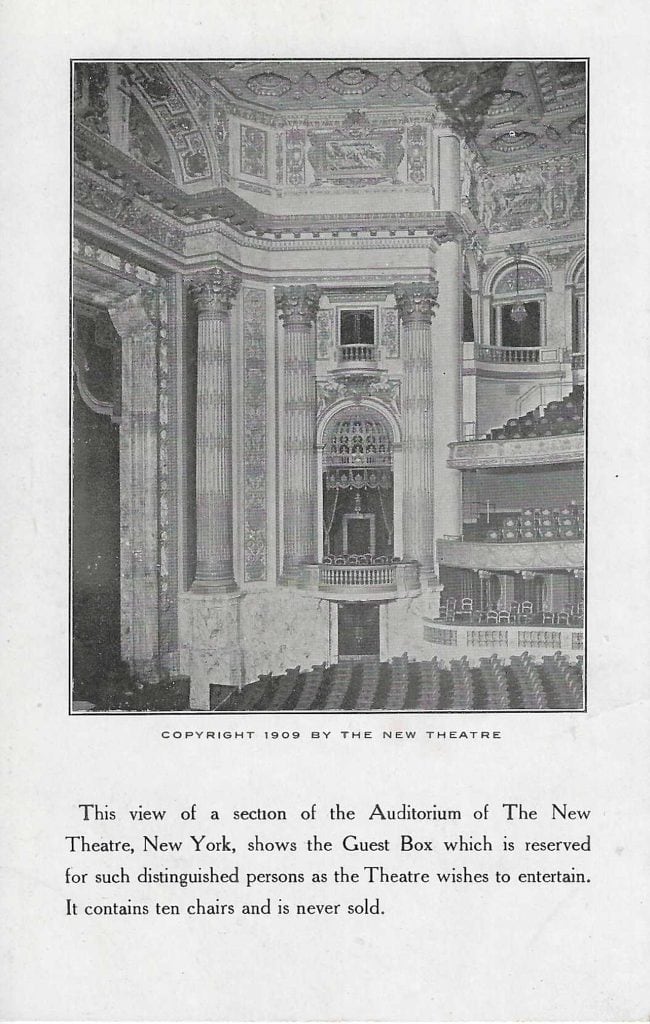

The New Theater, built at 62nd Street and Central Park West, embodied the expectations that investors hoped would reanimate legitimate theater. Among the early financiers and founders were William K. Vanderbilt, president of the association managing the enterprise, Otto H. Kahn, its treasurer and John Jacob Astor, an influential benefactor of the arts. The massive structure designed in the Italian Renaissance style, seating 3,000 and costing nearly $3 million, was expected to become a showcase for both drama and opera. A select committee of society women would decide upon the eligibility of applicants for the theater’s thirty sumptuous boxes. It was a formula that couldn’t miss, they thought.

An inauspicious opening night at the New Theatre on November 6, 1909, should have warned the investors immediately. A.H. Sothern and Julia Marlowe flopped in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra blaming it partially on the out-of-scale stage which reduced their intimacy. They never returned to the New Theatre. Despite organizing a drama school and regardless of a series of architectural renovations reducing the size of the stage, the auditorium and the number of boxes, nothing worked.

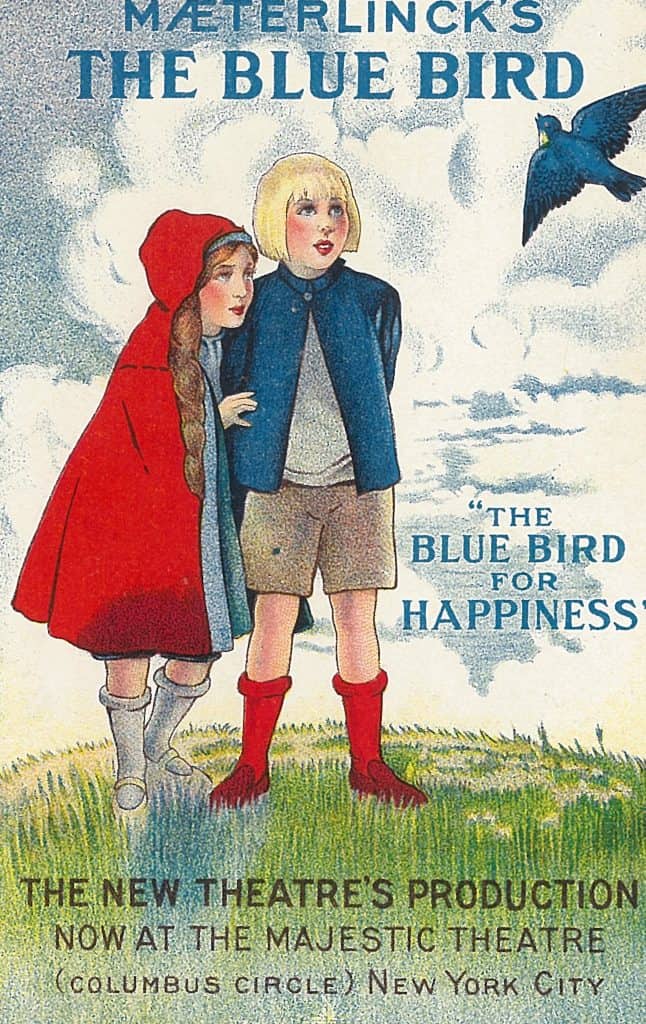

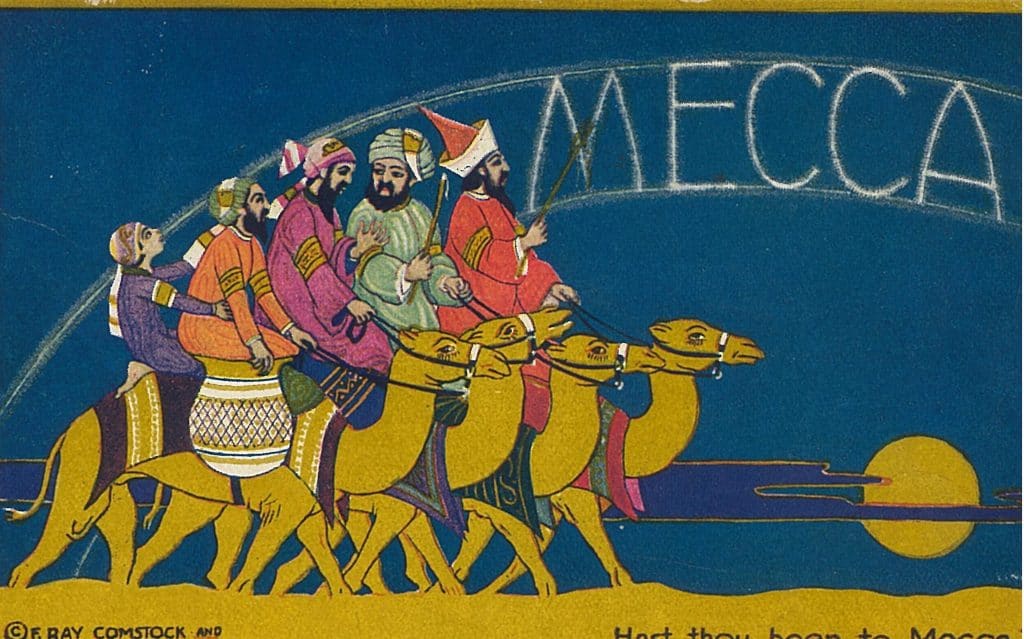

New management better aligned with popular tastes tried rebranding as the Century Theatre. They altered the mix of performances to include more musical choices and issued numerous sumptuous postcards to advertise their productions like the ones for Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird and Mecca by Oscar Asche with music by Percy E. Fletcher and choreography by Michael Fokine. Nevertheless, they just could not get audiences to turn out for the shows.

The Century abandoned the effort by 1929 and replaced the theater with the Century Apartments developed by Irwin Chanin. The building became an Art Deco exemplar for New York’s luxurious high-rise dwellings and still stands today.

New York City still needed larger theaters and still wished to push the boundaries of the Theater District beyond Columbus Circle. A plan for a substantial performing arts district began to gain adherents in the 1950s and eventually led to the establishment of Lincoln Center during the next decade – complete with a new home for the Metropolitan Opera.

This series will continue by examining how live theater survived and thrived despite new competitive forces. Legitimate theater was caught between the revue trend, vaudeville, and the growth of filmed entertainment. In balance, it could count on creative efforts emanating from “Off-Broadway” theaters in Greenwich Village and from support groups like the Theatre Guild, The Group Theatre, and the Roundtable at the Algonquin Hotel. The result was no doubt the most prolific and productive endeavor in the history of American theater – a story told on the postcards they published.

Fascinating, thank you.

The most money I ever made from selling a postcard was paid by a Cats aficionado who coveted my pre-World War II view of the Winter Garden Theatre.