After the Great War American audiences finally became comfortable with the engaged theatrical innovations that emanated from Europe, in some cases before the turn of the century. The social realism of Ibsen, Chekov, and Strindberg began creeping into the works of American playwrights. George Bernard Shaw’s plays started recovering from the antipathy that initially greeted his creative direction because of his political and ethical stances.

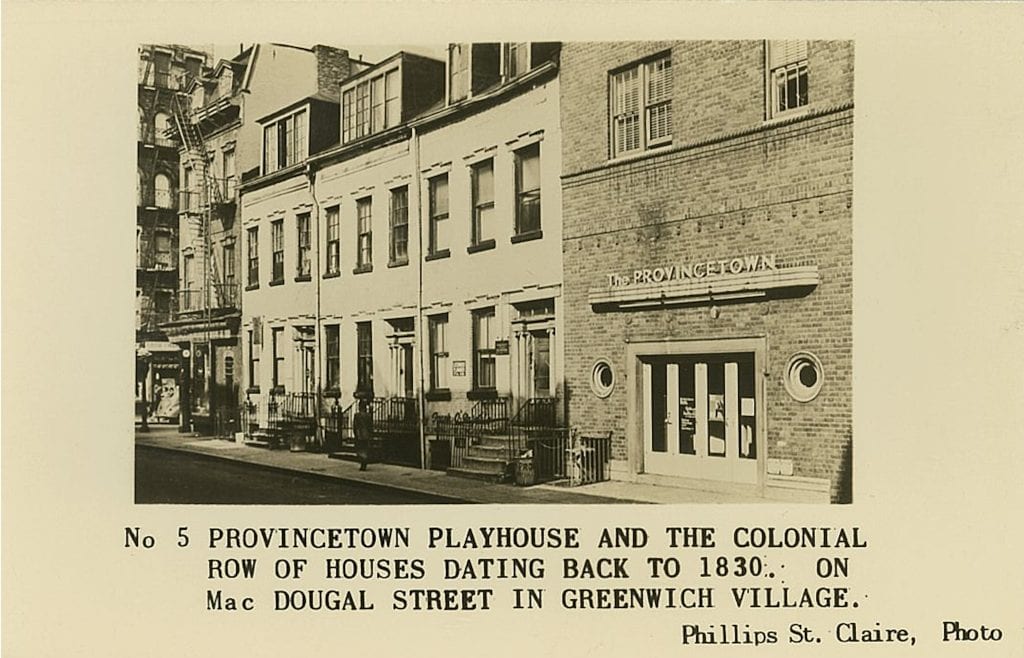

The influence of amateurs bringing theatrical passions acquired during wartime overseas travel or tourism, cannot be underestimated. The most influential of these were a group that formed on Cape Cod, putting on plays that emphasized innovative European and American writers and creativity. They came to Greenwich Village in 1916 creating the Provincetown Playhouse on Macdougal Street with playwright Eugene O’Neill as their leading light. At first, they occupied what had been a warehouse and stable but soon patched that up with a spiffy Art Deco renovation which has since been incorporated into New York University.

Most of all, the Provincetown Players led a movement that emphasized small theaters and collaborative groups working almost collectively to advance their craft and network their artists. They acted as a kind of innovation engine that nurtured both their personnel and audience in an “Off-Broadway” setting until selected prospects were ready for a move uptown to a larger audience, greater competition in popular entertainment and merciless critics.

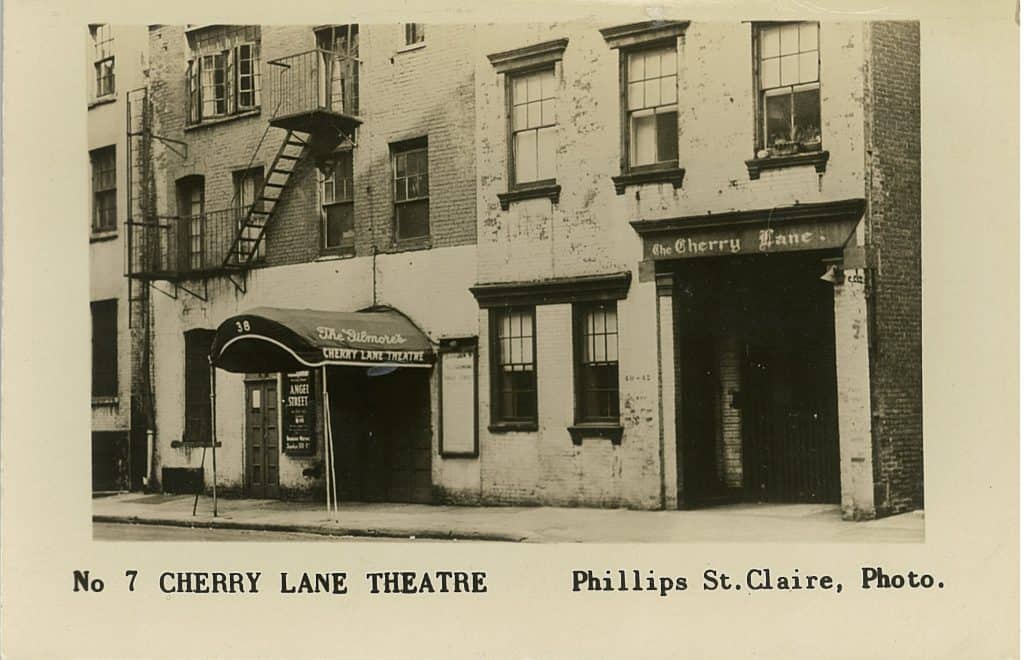

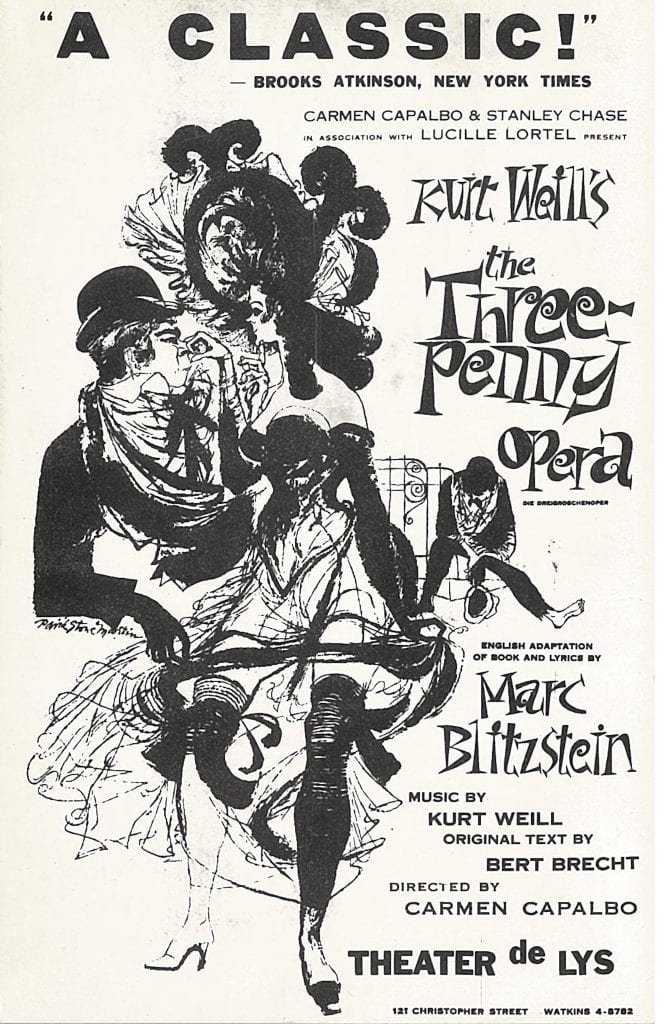

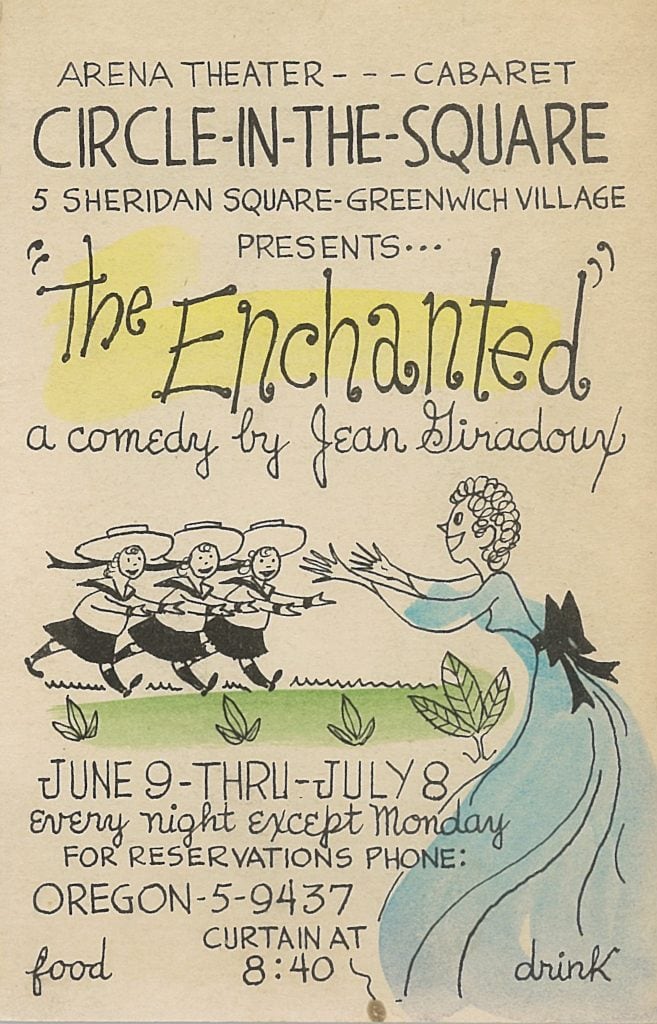

Off-Broadway has lasted for many years as an environment where innovation in theme, character and production has taken place, partly illustrated in postcards from the

Theater de Lys, which eventually became named for actress and innovative play producer Lucille Lortel. The renaming followed her grandly successful revival of the Weimar Republic’s sensation, Kurt Weill’s The Three-penny Opera. Circle in the Square, after many years of producing “theater in the round” on Sheridan Square and Bleecker Street, has finally moved uptown to the Broadway theater district. The Cherry Lane Theater remains a committed stalwart in its original location on Commerce Street snagging kudos as New York’s longest running Off-Broadway theater. It boasts an unparalleled record of having produced the works of leading playwrights including Dos Passos, Fitzgerald, and Elmer Rice in the ’20s to O’Neill, O’Casey, Odets, Auden, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot and William Saroyan in the ’40s and ’50s to Beckett, Albee, Pinter, Ionesco, and LeRoi Jones in the ’60s to Sam Shepard, Lanford Wilson, Jean-Claude van Itallie, Joe Orton, and David Mamet in the ’70s and ’80s

An offshoot of the Provincetown group became the Washington Square Players and after 1919 they morphed into the Theater Guild, described by Broadway historian and critic Brooks Atkinson as “the most enlightened and influential theater organization New York has ever had.”

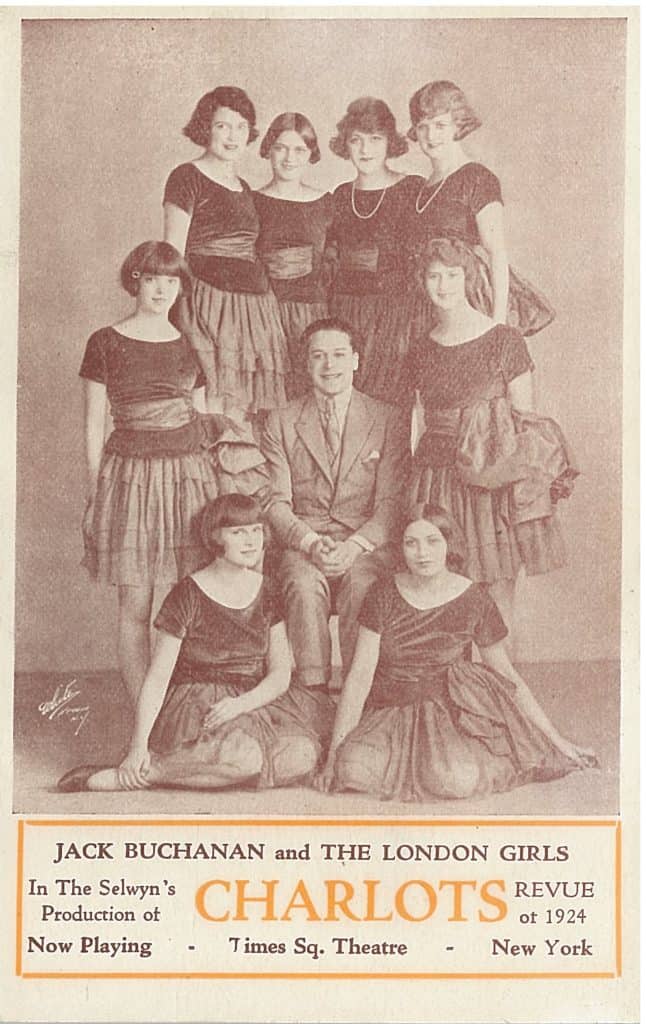

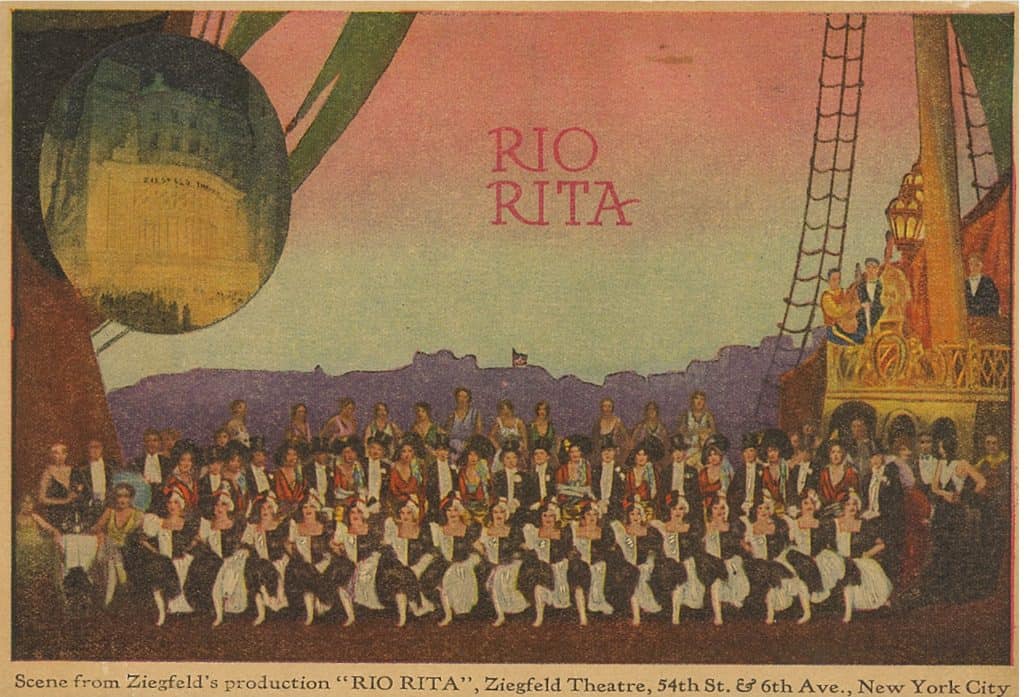

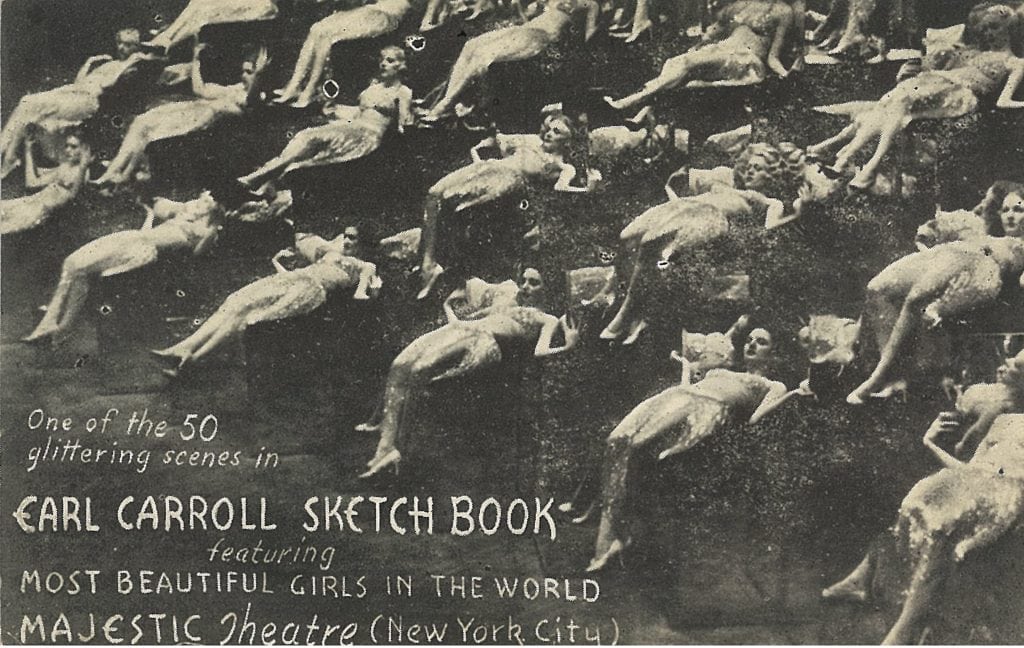

In the meantime, in the uptown theater district, the revue trend initiated by Florenz Ziegfeld could not be suppressed, encouraging many more productions noted for their sensual topics and leggy chorus lines. This trend advanced the careers of men like Earl Carroll and Jack Buchanan but did little for those legions of choristers.

The late 1910s and 1920s were supreme for theater building. Broadway ended up with about 70 or 80 theaters and in 1928 mounted 264 productions, their all-time peak. The most sumptuous was the Ziegfeld Theatre designed by Joseph Urban and Thomas Lamb in a beautiful Art Deco Style which, unfortunately, could not survive through conversion to a movie palace and TV production studio before its destruction in 1966.

Gigantic movie palaces eventually changed the opportunities for legitimate theater on Broadway. After the introduction of “talkies” with Al Jolson as The Jazz Singer in 1927 the decline turned into a rout. By 1950, thirty-six houses were left to cover legitimate theater. After some recovery of theaters featuring musicals at the close of the 20th century, that number has risen to forty-one Broadway theaters today.

The real world was impinging on 1920s Broadway creating a sensibility that could not disregard the reality of 116,516 American deaths on European battlefields during World War I. Reality included the Actors Equity Strike of 1919, the anti-communist Palmer Raids of 1920, the imposition of Prohibition and the arrival of new social types like the gangly flappers and members of the “Lost Generation” who sought meaning in disquietude.

The ugliness lurking underneath conventional life became a common theme taken up by many writers, especially those influenced by the psychoanalytic work of Sigmund Freud. Sinclair Lewis begrudged the righteous small town; F. Scott Fitzgerald exposed the hypocrisy of sophisticated society; William Faulkner was ruthless about villages in the American South. Similarly, Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms explored themes of incest and greed in the idyllic American farm. He didn’t stop there. Attempting to adapt the structure and emotional intensities of Greek tragedies, O’Neill’s street-drawn characters’ undersides are riddled with weakness, guilt, mistakes, cruelty, ruthlessness, and violence. He was also prolific and given to innovative staging, using techniques like asides to the audience and soliloquies. He won four Pulitzer Prizes for drama and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936. O’Neill became the most widely produced playwright after Shakespeare and Shaw.

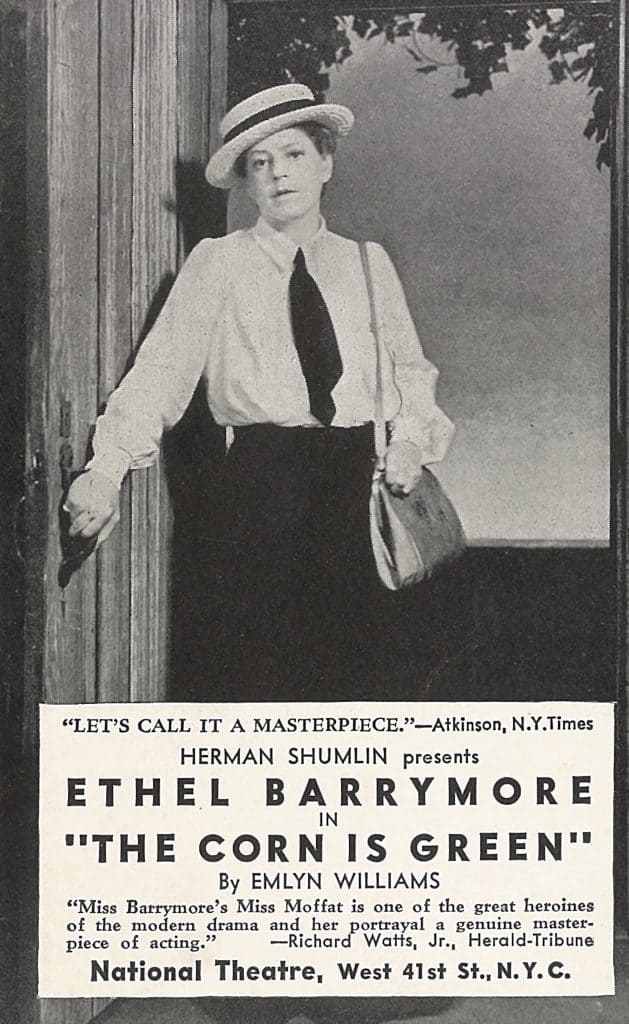

Broadway stayed vibrant through the Depression and World War II years on the strength of outstanding theatrical writers and effective production companies. They also shared a small cohort of superstars that maintained the highest standards and brought in devoted followers. The most highly recognized among these actors were Ethel Barrymore, scion of a large extended multigenerational family practicing the craft, and the ensemble team of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne.

In 1940, Ethel Barrymore, the doyenne of Broadway veterans was induced by the gifted and imaginative upstart producer Herman Shumlin to cap her 50-year career as Miss Moffat in The Corn Is Green. The role of a hardened Welsh schoolteacher who softens and regains her optimism working with a promising apprentice helped Barrymore demonstrate the range and depth of an authentic master. Afterwards, her career became legendary in both stage and screen until her death in 1969.

Married theatrical partners Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne appeared together as the Lunts and were associated with the Theater Guild on both sides of the Atlantic from the 1920s through the 1960s. They were known for working with the best of classical and contemporary playwrights including S. N. Behrman, Noel Coward, and Robert Sherwood in comedies of manners and romance and for projecting a kind of lusty eroticism with intimations of sexual experimentation. Lunt extended his career as a director, even moving into productions like Cosi Fan Tutte at the Met Opera.

Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight premiered on Broadway at the Shubert Theatre running from March 24, 1936 for 300 performances. The play won the 1936 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the first of four Pulitzers (three for Drama, one for Biography) that Sherwood received.

Our next installment, Act 5, will advance our postcard history of Broadway theater with continued discussion about the production companies like the Theater Guild and Group Theater that produced the masterpieces in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. We will also describe Broadway’s engagement with the social issues of our time with special attention to the Civil Rights movement. Finally, we’ll cover Broadway’s shift from dramas to musicals and theater’s decline and resurrection in the 1970s and 1980s.

Bravo!

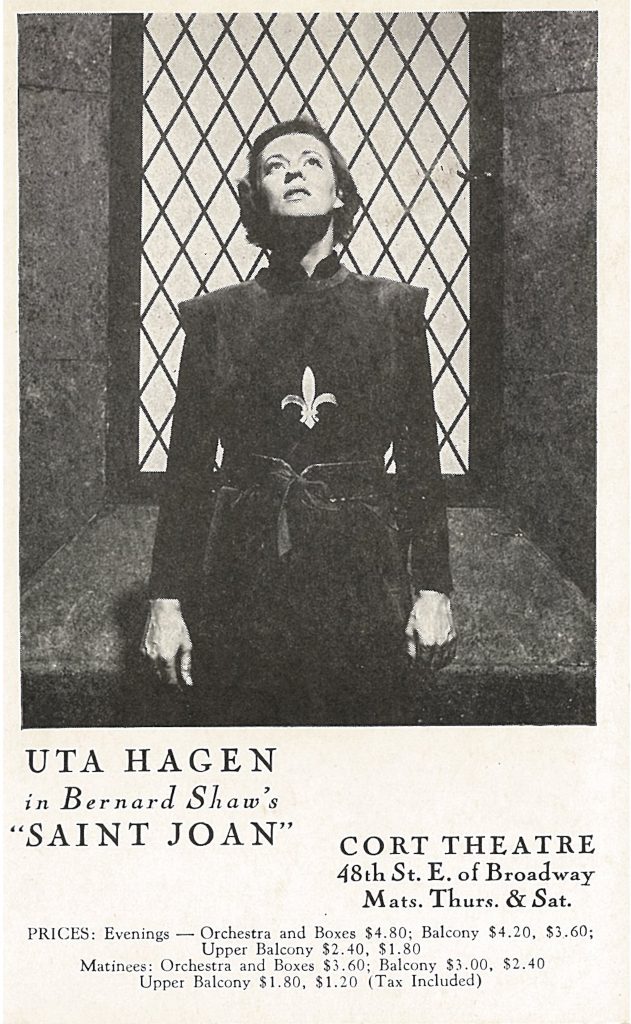

It’s nice to see a card featuring Uta Hagen, who was a respected performer and acting teacher but whose name survives in the American consciousness mostly as a standard crossword clue.

A wonderful article!!

Still more incredible views of Broadway, exteriors, performers, and interiors too. Thanks for this pair showing the Provincetown Playhouse. So much history, so many names that we remember, and many more that are new to us. Thank you Hy for this series and the depth of research and writing that you share with us.

Brought back some memories of the films ‘Desire under the Elms’ and ‘The Corn is Green’.

Hy’s articles are so interesting. Thanks