The following definition of a parable certainly will never mirror the one found in any version of The Merriam-Webster Dictionary because it is mine and it works well as I teach English as a second language.

A parable is a short story that illustrates the principles of life.

A parable is not a fable. The characters in a fable are plants, animals, and things, whereas the characters in a parable are humans – sometimes with and sometime without their best intentions on view. According to the self-appointed masters-of-the-craft, Aesop wrote (or retold) fables; Jesus laced his sermons with parables and should be considered the only true “parablist.”

The Aesop part of this conjecture is easily illustrated in the title of his Fox and the Grapes. Can there be a debate? Likely, not! However, the part about a single individual being the “only” is nullified the instant you learn that the parable of Akhfash’s Goat has a Persian origin.

Akhfash is a solitary man who speaks only to his goat. While the reasons for his isolation are left unclear, it is possible Akhfash found himself friendless after being too forceful in his attempts to convince others to accept his beliefs. Akhfash may have tried so hard to persuade others that he was left with only his goat to listen to and agree with him.

An abstract of it implies that a Persian philosopher trained his goat to nod its head every time it is asked if he understands the principles put forth by another. The lesson learned is that “Akhfash’s goat” is a reference to a person who nods along with a conversation that he is expected to comprehend but has absolutely no understanding of the content. The conclusion drawn is that the goat is a fool who agrees without thinking.

In nearly every language and in nearly every culture there are parables. Some are told or transcribed in prose, but equal numbers are poetic. Two of my favorites are The Son and the Father and The Farmer’s Crops:

The Son and the Father

Every age has its bitter, every age has its grief:

Son toiled o’er his book, father was vexed beyond belief.

The one had no rest; the other no freedom, forsooth:

Father lamented his age, son lamented his youth.

***

The Farmer

The farmer was bent on doubling his profits off the land,

He proceeded to set his soil to a two-harvest demand.

Too intent was he to profit, for himself and his needs:

Instead of corn, he now reaps flowers and weeds.

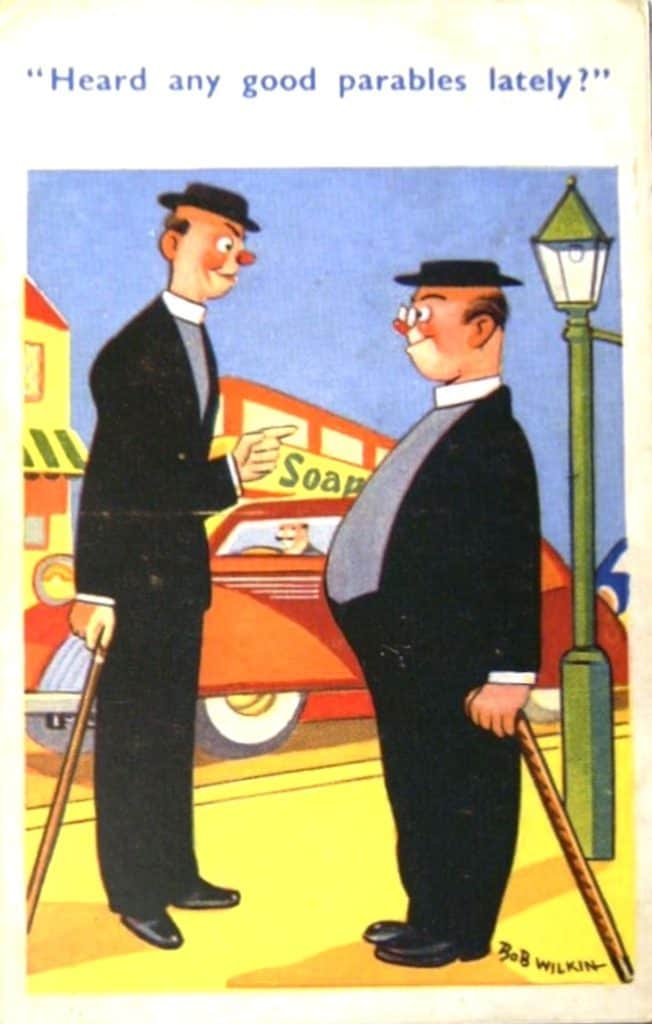

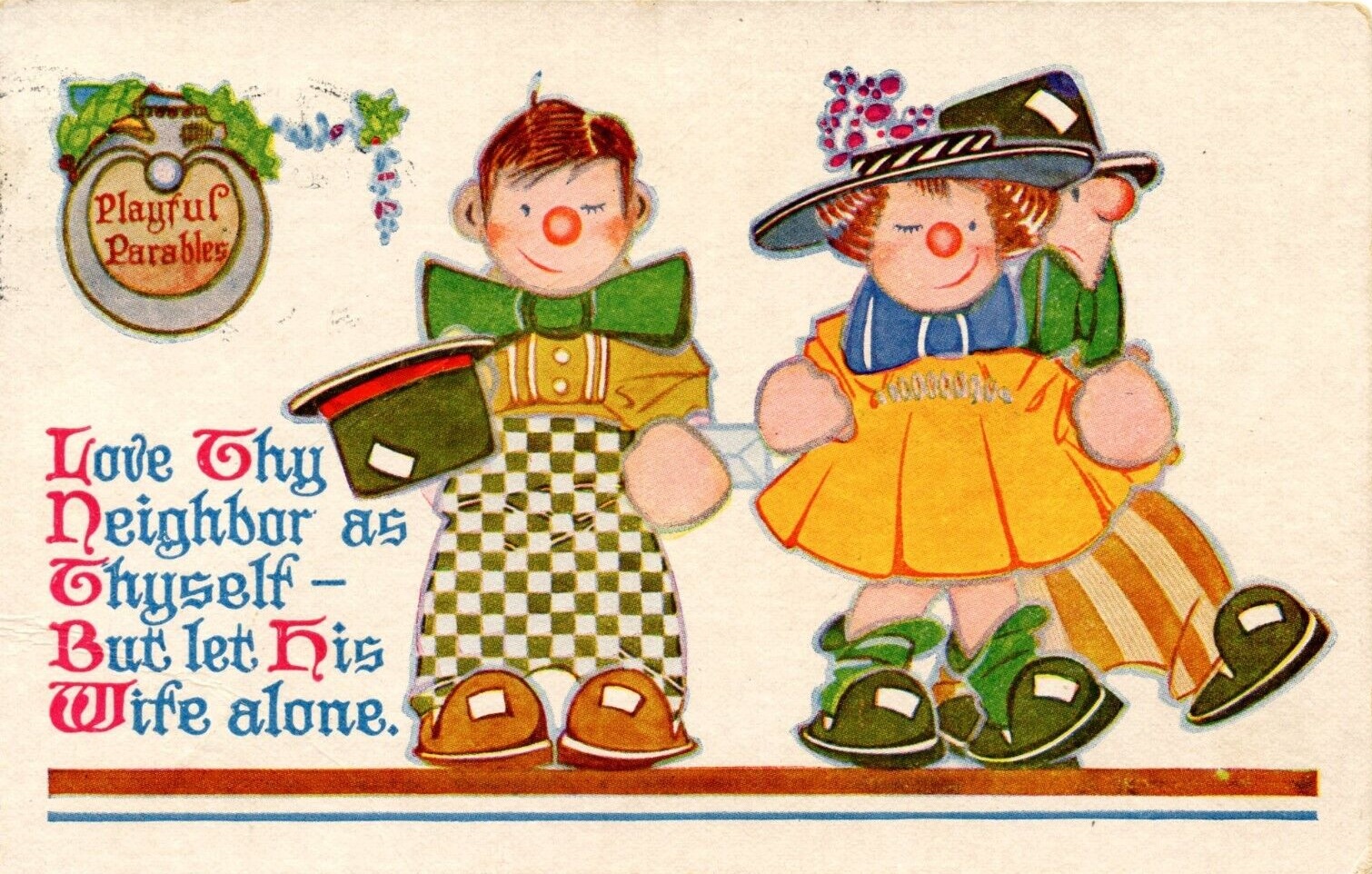

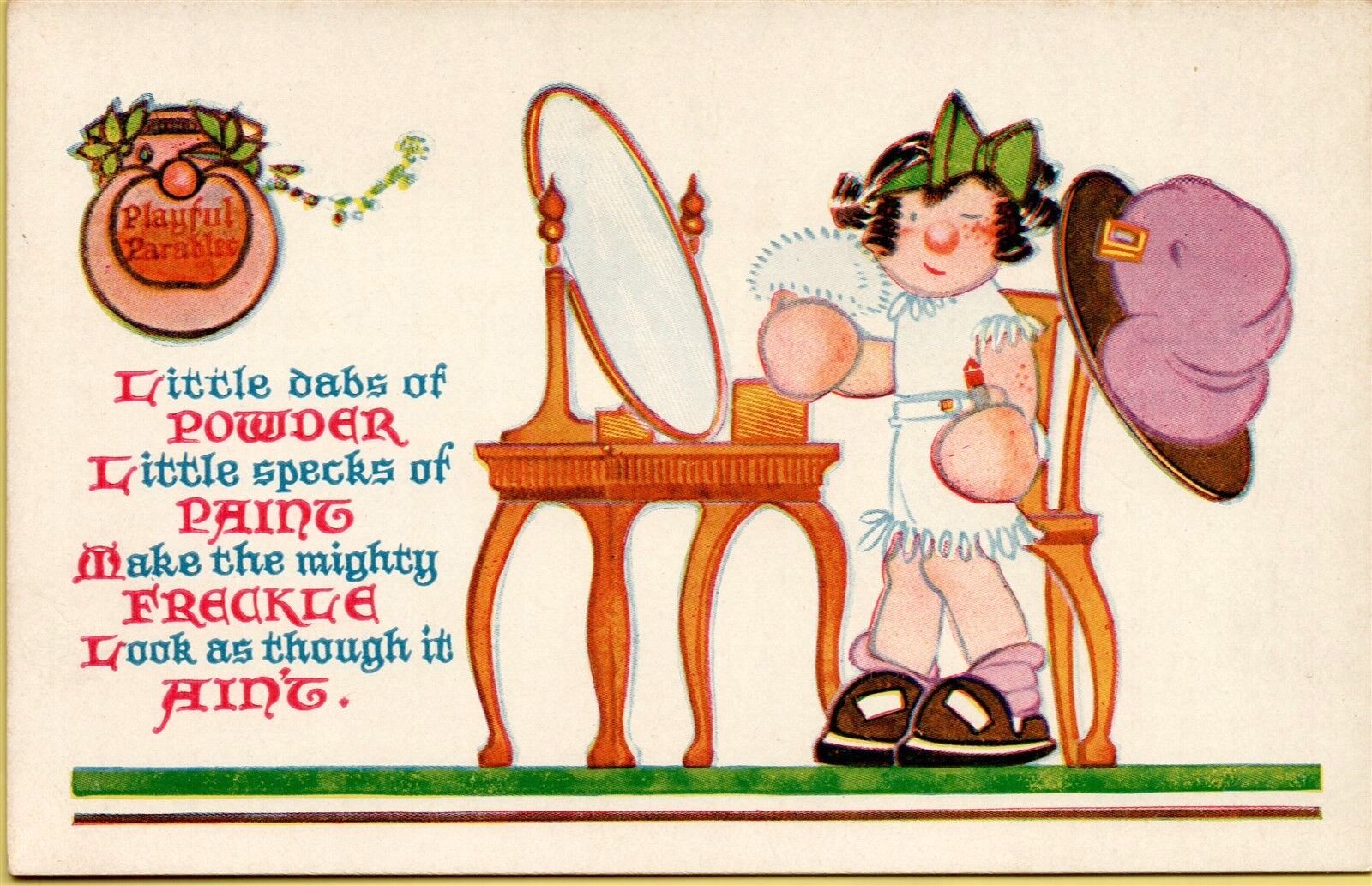

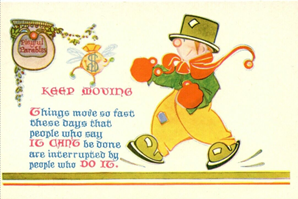

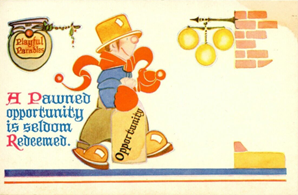

The lessons learned from parables are often meant to amend minor behavior faults, but there are equal numbers that are frivolous and mischievous like the “Playful Parables” published around 1906 in Boston by the Typo Postcard Company.

A rhetorical question that may arise is, “Has the word parable been highjacked by spiritual factions? There is no definitive answer and when all things are considered, it simply does not matter since the word is seldom heard in speech and seldom used in text.

Yet the following fact remains: the meaning of the word parable has not altered or modified for nearly eight-hundred years. I base this on my own research in dictionaries of the English language published in three nations, Great Britain, the United States, and South Africa.

The Oxford English Dictionary, one of the most reliable reference books on the English language, sets the etymology (the history and meanings of words) of parable as a noun to about the year 1250. The OED definition follows, a realistic story or narrative told to convey a moral or spiritual lesson or insight; especially, ones told by Jesus in the Gospels.

In America, two dictionaries have held sway in the years since 1828. An American Dictionary of the English Language first appeared as a two-volume work ostensibly written by the American lexicographer Noah Webster. The completed work took nearly twenty years, it contained 12,000 words and more than 30,000 definitions based on – this is important – spoken English.

Webster’s definition since 1928 has been, A short fictitious narrative of a possible event in life that teaches a lesson of a moral or spiritual nature.

The other American (Funk & Wagnalls) dictionary was A Standard Dictionary of the English Language. The first edition was published in 1893 – and this is important, too) with definitions based on written as well as spoken English. The company was founded by Isaac Funk in 1875. In 1877 Adam W. Wagnalls (one of Funk’s classmates in college) joined the firm and the corporate name was changed to Funk & Wagnalls Company. Their definition of parable is quite similar, A brief tale in prose or poem that is instructive for use in improving the moral or spiritual character of a lost soul.

Not surprisingly the word parable does not appear in The Dictionary of South African English, hence the word’s meaning is considered “standard” and unworthy of special considerations.

In closing, dear reader, allow me to ask you a question …

Why did the dictionary cross the road?

So, he could visit his “grammar” and to get his “meaning” across!

Grammar? Now, that’s a story for a different time and different place. And a whole other set of postcards.

An enjoyable and interesting read.

I find it interesting that the Funk & Wagnalls definition is so overtly “preachy”, and that the South African dictionary does not include definitions of “standard” words when an American dictionary features such basic terms as “dog” and “good” in addition to arcane nouns and adjectives

I’m surprised South Africa still allows dictionaries. The illiterate government will tell you all you need to know.