Seventy-seven years have passed since Gertrude Stein died in 1946, and she is still a controversial figure. She was an American who lived in France, she was a writer who published too little, and a critic who criticized no one. And when her name is mentioned in any circumstance it is nearly impossible to exclude her life-partner Alice B. Toklas.

Toklas was born in San Francisco and moved to Paris in September 1906 after an earthquake destroyed most of her hometown. She met Stein the day after she arrived. It would take a full-fledged psychological analysis to explain their attraction to one-another, for it was common knowledge that Toklas was an obsequious, mousy individual with almost nothing in common with Stein. A friend and business partner described their relationship in an editorial eulogy of Stein: Toklas “was a little stooped, somewhat retiring and self-effacing. She doesn’t sit in a chair, she hides in it; she doesn’t look at you, but up at you; she is always standing just half a step outside the circle. She gives the appearance, in short, not of a drudge, but of a poor relation, someone invited to the wedding but not to the wedding feast.

Some weeks ago, I introduced the readers of Postcard History to my collection of Salome postcards. When that happened, I shared 13 of about 60 cards. This contribution will be much smaller since I have only 16 cards of Stein. You will however find a surprise in the conclusion.

In an attempt to escape the turmoil of Pre-World War I society, that disregarded nearly every kind of art form in favor of the dollar, Gertrude Stein became an expatriate and was the first American to respond to European avant-garde art. She held weekly salons in her Paris apartment. Single-handedly she, with some help from Alice, popularized both European and American writers like Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ezra Pound, and artists like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as examples. To go a step further, Stein’s support and friendship were the foundation of Picasso’s success.

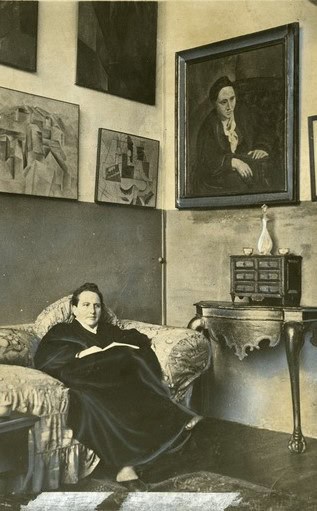

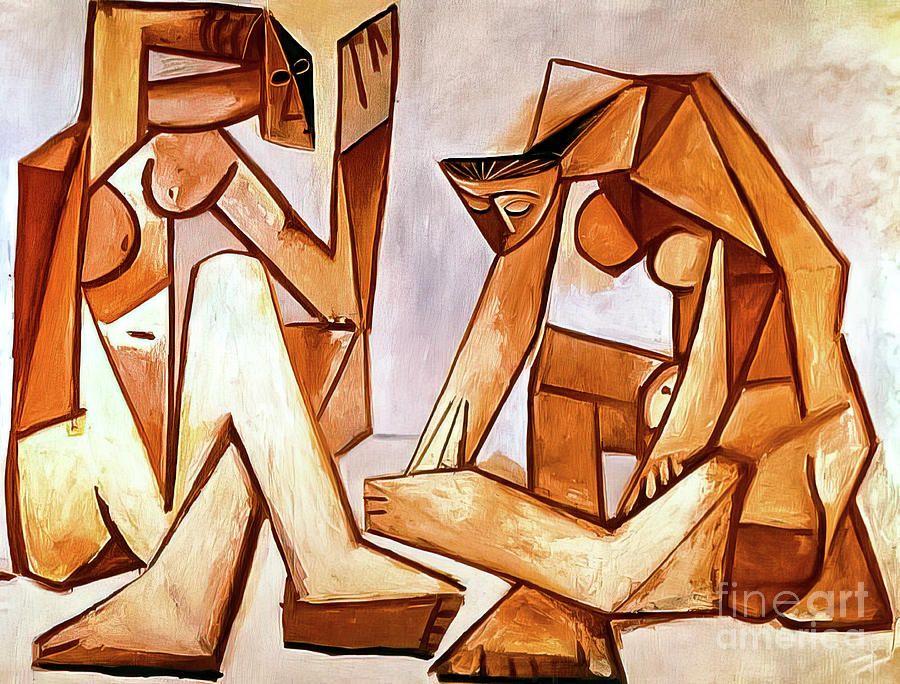

Picasso painted his portrait of Stein between 1905 and 1906 at the end of his so-called “Rose Period.” At a public gathering shortly after its completion, someone said that Stein did not look like her portrait, Picasso replied, “She will.” He reduced her body to simple masses and portrayed her face more as a mask with heavy lidded eyes, reflecting his recent encounter with Iberian sculpture.

Twenty-first century art students look back at the various periods of Picasso’s art and find it difficult to assign and align the color periods (blue and rose) and the primitivism and cubism periods, then with his Neoclassicism and surrealism periods that caused Picasso to be considered one of the most versatile artists in history.

In depth discussions of Stein frequently ignore her years as a medical student at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. William James, who had become a committed mentor to Stein at Radcliffe, recognizing her intellectual potential, and declaring her his “most brilliant woman student,” encouraged her to enroll in medical school. Although she cared little about the practice of medicine, she enrolled at Hopkins in 1897. In her fourth year, Stein failed an important course, lost interest, and left. Ultimately, medical school had bored her, and she had spent many of her evenings not applying herself to her studies but taking long walks and attending the opera. Proof perhaps that Paris was a much better “fit” for her than Baltimore.

Another frequently ignored period in Stein’s life are the years between 1903 and 1914 when she and her brother Leo shared a common household along the Left Bank of the Seine River. It was also the studio for their jointly owned, later to be infamous, art collection.

Infamous because upon Stein’s death, it was discovered by her family that she willed her art collection to Toklas, a situation over which the Stein family took high umbrage. Police actions and lawsuits ensued to the pleasure of no one.

Perhaps the one thing in life that Stein and Toklas both loved was a full-size white poodle named Basket. Their first dog died in 1937 which was immediately replaced with another standard poodle that was given the same name. Basket Too was just nine years old when Stein died, but no one filed suit over the dog.

Basket is only one example of how much Stein liked repetition. The sentence “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” was written by Gertrude Stein as part of the 1913 poem Sacred Emily, which appeared in the 1922 book “Geography and Plays.” In that poem, the first “Rose” is the name of a person. Stein later used variations on the sentence in other writings, and the shortened form “A rose is a rose is a rose” is among her most famous quotations, often interpreted as meaning “things are what they are,” a simple statement of identity.

The conceptualization of repetition and identity brings my essay back to the influence Stein had on Picasso. Because Stein was 32 years old when she met Toklas who was 29, it may be difficult to picture them as svelte young women, but apparently Picasso did.

Throughout his career Picasso would do paintings with similar names based on nearly identical concepts. What can a practice such as this be called except repetition? Because art historians disagree more often than can be imagined, I have included three of my favorite Picasso postcards here simply because it has been suggested that Picasso used Stein and Toklas as subjects for the original Two Women at the Sea and the two cubist era paintings he did decades later.

Arthur Kopit’s play Chamber Music features eight women in an insane asylum, all of whom claim to be historical figures. Gertrude Stein is among the impersonated.

I think the best way to describe Alice is as Gertrude’s wife. No need for a full-fledged psychological analysis.

Such an interesting article! Great Post cards