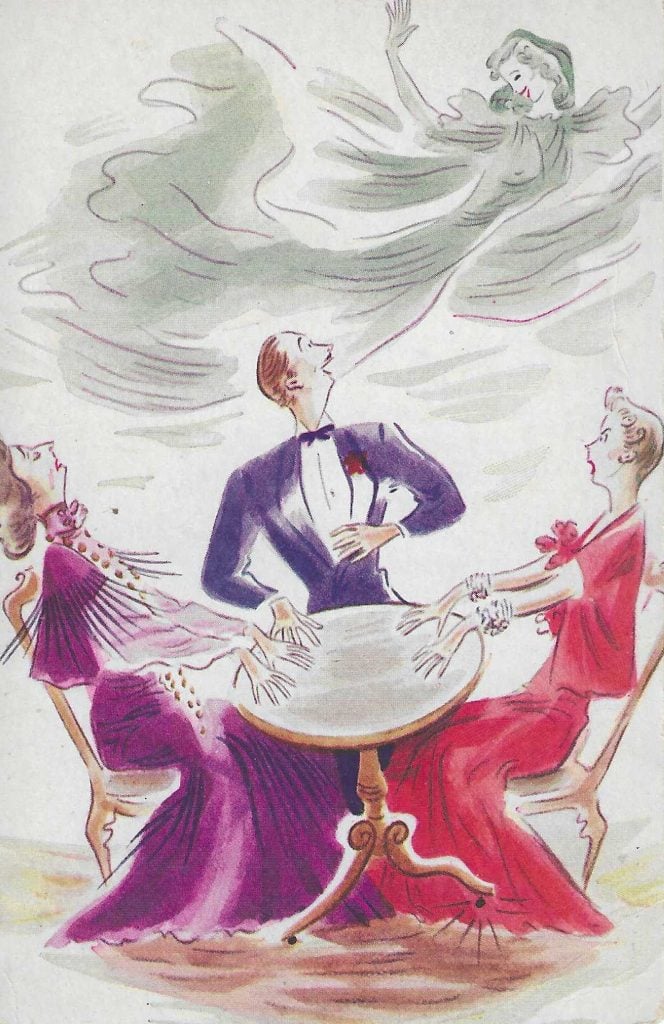

Contemporary Broadway history owes a great deal to Theater Guild, founded in New York City in 1918 for producing the best and the brightest American theater had to offer. Bringing the work of George Bernard Shaw to America, they then supported the controversial opus of Eugene O’Neill and other playwrights like Robert Sherwood, S.N. Behrman and Noel Coward. That was just the start, however, and their influence was wider and deeper. Coward’s “comedy about ghosts,” Blithe Spirit, played successfully in both London and New York starting in 1941 and was successively made into a film and a musical.

The classics were big hits in midcentury. The Lunts, Alfred and Lynn Fontanne could not resist connecting their inimitable chemistry to the Shakespearian classic about coupling Taming of the Shrew. Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic light operas also maintained their Broadway audience and in 1927 Iolanthe struck gold in the West End and in Times Square. A bit of escapism and relief from the stresses of depression and wartime could help explain the success of lighter fare as theater went into the 30s and 40s.

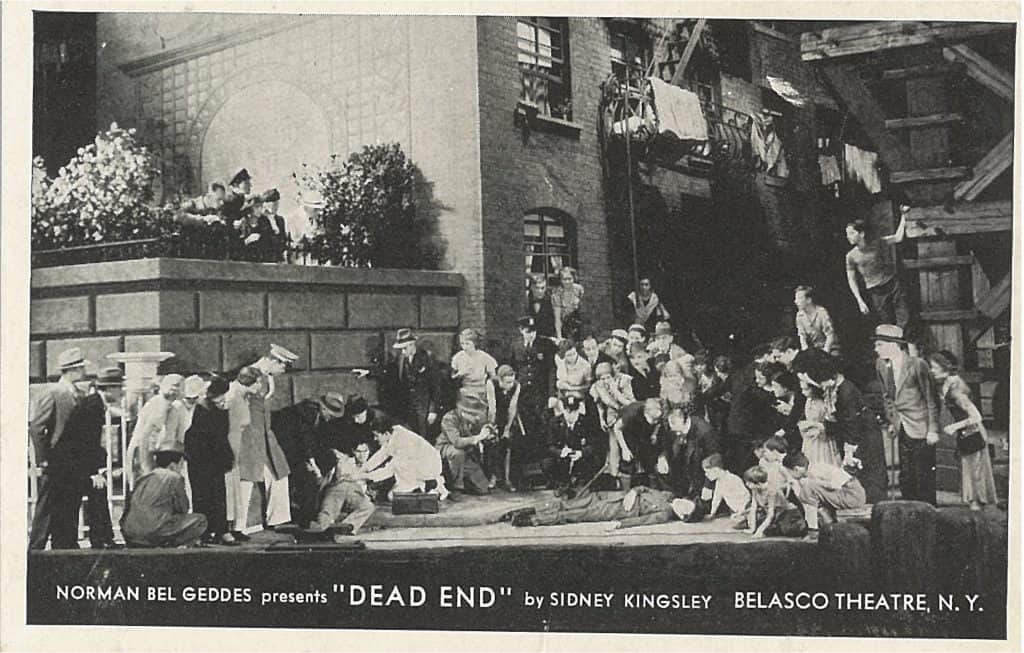

On the other hand, Broadway was also seeking engagement in the 1930s and 40s. Serious criticism of America’s class structure was on the project list. Sidney Kingsley’s 1935 Dead End was a quasi-ethnographic critique of challenges faced by children growing up on Manhattan‘s Lower East Side. After playing on Broadway for two years, it became a film and then a franchise, for what ended up as 89 films with more or less the same cast of characters known variously as the Dead End Kids, East Side Kids, Bowery Boys, etc. They became the darlings of the triple feature movie houses and sometimes drifted away from tragedy to slapstick and light comedy featuring the boys who became its leading men, Leo Gorcey and Huntz Hall. A memorable feature of the original production was using the orchestra pit to simulate the filthy East River as a swimming hole used by the East Side kids.

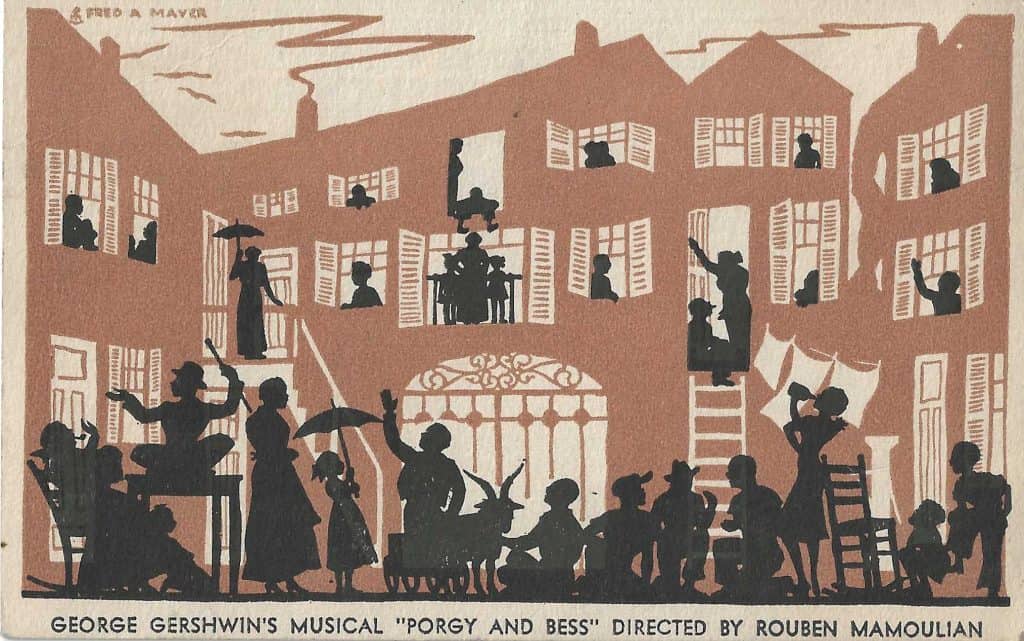

The Theatre Guild helped to organize the production of what has become America’s best theatrical work, whether you think of it as a musical or an opera, George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Based on an earlier play Porgy by DuBose Heyward, the libretto and lyrics were created by the husband-and-wife Heywards, DuBose and Dorothy, and George Gershwin’s brother Ira. Porgy and Bess continues to be performed very frequently and celebrated for its contributions to the Great American Songbook like “Summertime,” “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” and “Bess, You Is My Woman Now.” George who was Jewish and originated on the Lower East Side wrote the folk opera after living with his subjects in Gullah Geechee Country on Folly Island near Charleston, South Carolina, the source of much of the score’s cultural references and musical vocabulary.

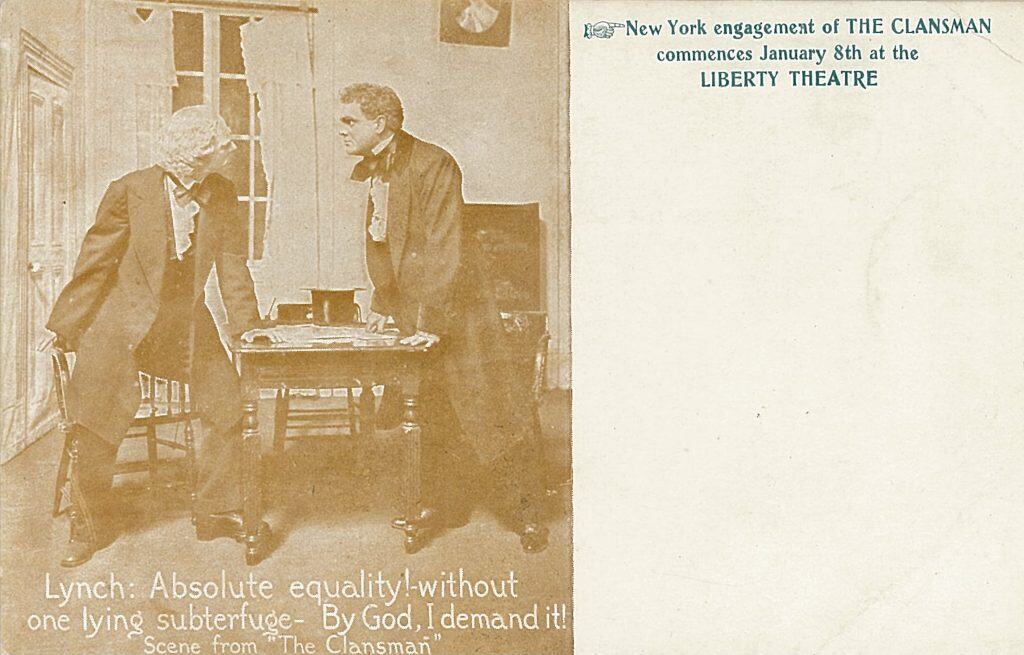

Broadway returned to its roots in African American plantation performance and minstrel traditions frequently to diversify its cultural representation and to engage its discussions of civil rights issues. It was not always an easy subject to master. A 1905 play by Thomas Dixon Jr., The Clansman romanticized the Ku Klux Klan in its critique of the Reconstructionist South. A decade later D.W. Griffith turned the property into a feature film, Birth of a Nation, which was widely shown though equally condemned for its unbridled racism.

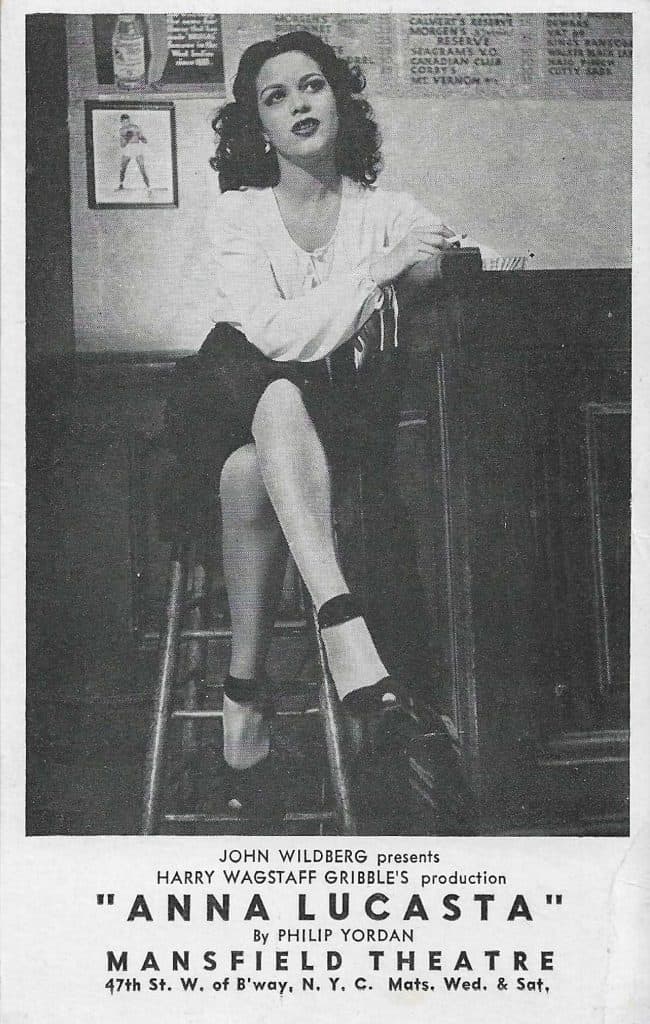

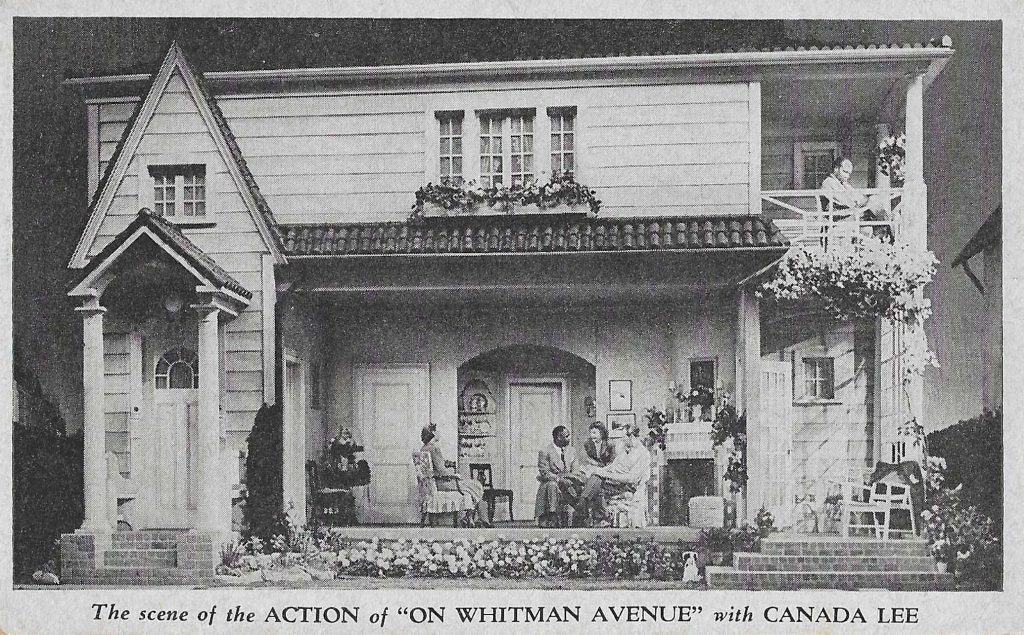

In contrast, as the Second World War was winding down in Europe, and American GIs were returning to a more politically engaged climate in America, the struggle for civil rights began to take center stage. The 1944 production of an allegorical romance about a “whore with a Heart of Gold,” Anna Lucasta authored by Philip Yordan, the “prolific screenwriter” was based on Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie. The all-Black production by the American Negro Theater Company was a solid hit for two years. Other shows that presented civil rights issues as they were becoming a major topic in the national dialog included the 1946 On Whitman Avenue with Canada Lee at the Cort Theatre. Elia Kazan’s 1945-46 staging of Deep Are the Roots is about a decorated African American soldier who returns from the war but finds he must confront many of the same disabilities of racism as before the war. Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 Raisin in the Sun showed that racial issues were as troubling in the north as they were in the south. The first play written by a black woman to be performed on Broadway, the show won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle recognition as 1959’s best play. This hit was an important career stop for actors Sidney Poitier, Ruby Dee, and Louis Gossett Jr. who also starred in the filmed version.

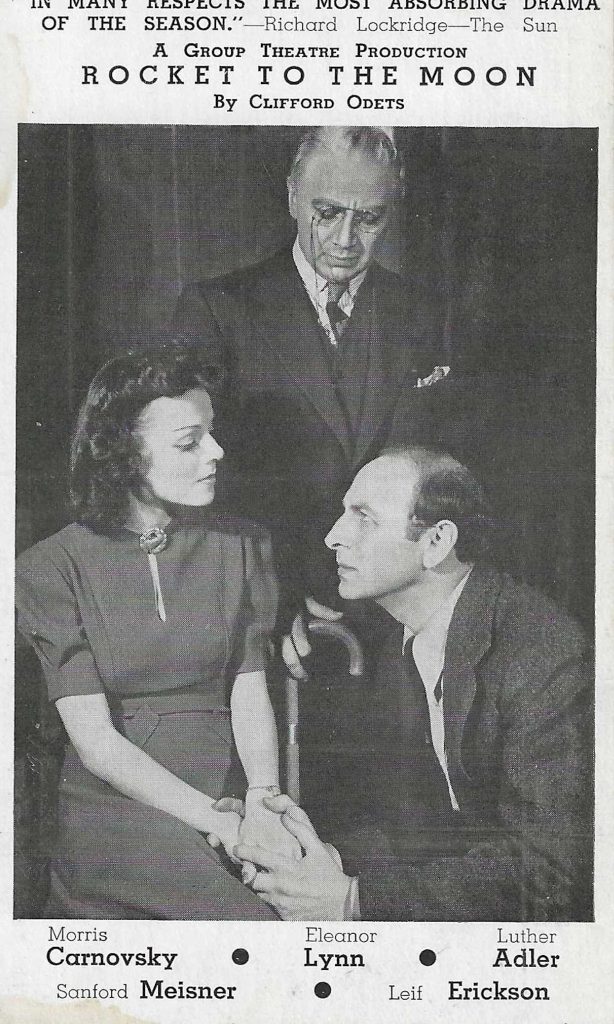

The Group Theater was another collective producing organization formed in New York City in 1931 by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford, and Lee Strasberg. Its leading light Clifford Odets was considered by many to be second only to Eugene O’Neill in the quality of his dramatic output. Devoted to “Method Acting’ or the “American Acting Technique” derived from the teachings of Konstantin Stanislavski, the Group Theater advanced a style that was forceful, naturalistic, and highly disciplined. Important playwrights working with the Group included Sidney Kingsley, Paul Green, and Irwin Shaw. Its acting troupe represented names that led Broadway drama for a generation.

Two key plays written by Clifford Odets in 1935, Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing are emblematic of the kind of work done by the Group Theatre in creating engagement, breaking down the barriers between cast and audience, fostering spontaneity and immediacy. Waiting for Lefty is based on a taxi drivers strike and deals with emotions and tensions about a strike vote. Some cast members are planted in the audience and emerge at key moments. Awake and Sing deals with the inner emotions of members of an extended Jewish family living in the Bronx borough of New York City as they struggle through issues of solvency and respectability while being roiled by the Great Depression and social change.

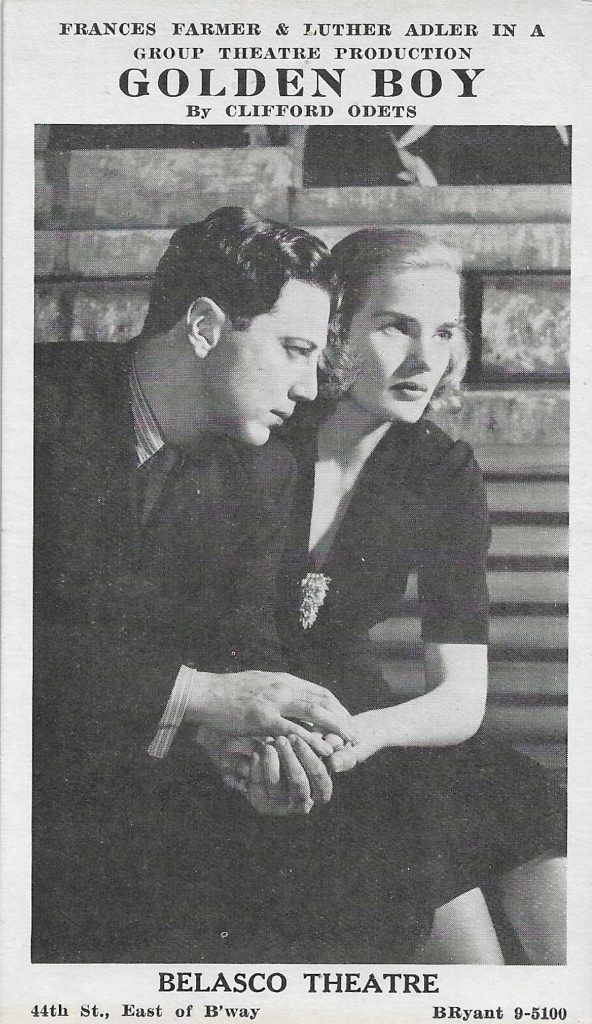

Odets moved from social justice to personal psychological conflicts in his 1937 Golden Boy which featured Luther Adler as Joe Bonaparte, skilled as both a boxer and a violinist, knowing that quick money as a pugilist could cause him to lose skills as an artist. Luther Adler as well as his sister and fellow Group Theater member Stella Adler were children of Yiddish Theater superstar and impresario Jacob Adler. Stella spent many years as a leading teacher of actors-in-training including important stars like Marlon Brando and Warren Beatty. Distinguished Group Theater stars included Elia Kazan, Sylvia Sidney, Franchot Tone, and Sam Jaffe.

Broadway theater projected a kind of maturity in midcentury, presenting the finest scripts and actors and dynamic productions. Its musical talent was unsurpassed. Broadway did this despite a challenging political and technological environment. It did not succumb to the difficulties posed by filmed entertainment or to the wartime experience which was reducing the audience and leading everyone to question their purpose.

The concluding final chapter of our Postcard History of Broadway – what we will call the “Encore” – will show how the wartime and postwar period helped to create the peak of the Broadway experience. This happened creatively just as social forces undermined the entire theatrical enterprise.

The most grievous force undermining theater was the deterioration of urbanism in general through suburbanization during the postwar period. This paralleled the restructuring of home life. It was suddenly a more family-centered, paternalistic enterprise with a greater emphasis on religion and socialization of children – all hard to reconcile with experimentation and challenges to orthodoxy. As urbanism declined there was also a deterioration of the urban lifestyle. Nightclubs closed; chic urban hostelries disappeared. Attending live theater performances stopped being a priority. A kind of moodiness and introspection developed. The boozy world of revelry and dissipation was reserved for places like Las Vegas and college campuses. Nighttime at home became dominated by inexpensive recordings and television.

Excellent and highly informative! Thank you kindly.

Interesting article Hy. I love the Porgy & Bess card! I’ve seen it performed on Broadway twice, so my opinion is Great Musical not Opera.

I try to catch Porgy & Bess every time a “new” production comes through town. The most recent one was just before the pandemic at the Metropolitan Opera with Angel Blue (who also does an amazing Tosca) and a very operatic cast. My tears are reliably jerked every time Bess leaves Porgy as much as when Pinkerton cruelly deserts Cio-Cio San. Nevertheless, the Opera vs. musical theater question is one that I’ll never tire of debating. While we’re at it, where do you stand with West Side Story?

The Porgy and Bess postcard of the cast in silhouette has long been a special favorite of mine, and it was great to see this here in this part of your wonderful Postcard History of Broadway. This is the only postcard of the many you have featured in this series, that I own. It was like seeing an old friend, again. I love it so much. Thanks, Hy for all of your effort and hard work that goes into your explaining and teaching us about Broadway.

I once met a guy who had been one of Lee Strasberg’s final students before the legendary acting teacher died in 1982.