The postwar ex-soldier was concerned with material success, the trappings of affluence, and spiritual succor, a reawakening from years of deprivation, conflict, and terror. Broadway could fit into this new ethos, but it was not going to be easy.

Fortunately, Broadway had developed a star system filled with major talents whose skills as writers, actors and performers helped them take advantage of opportunities rather than get defeated by advances in motion pictures, radio, and television. A case in point is Lillian Hellman’s 1939 contemporary classic about greed, jealousy and other family dynamics in the Deep South, The Little Foxes, starring Tallulah Bankhead. By 1941, William Wyler had a filmed version on the street starring Betty Davis. Little Foxes ran for two years in Times Square and then went on a successful national tour for another two years. It proved that to some extent, live performance could coexist with film.

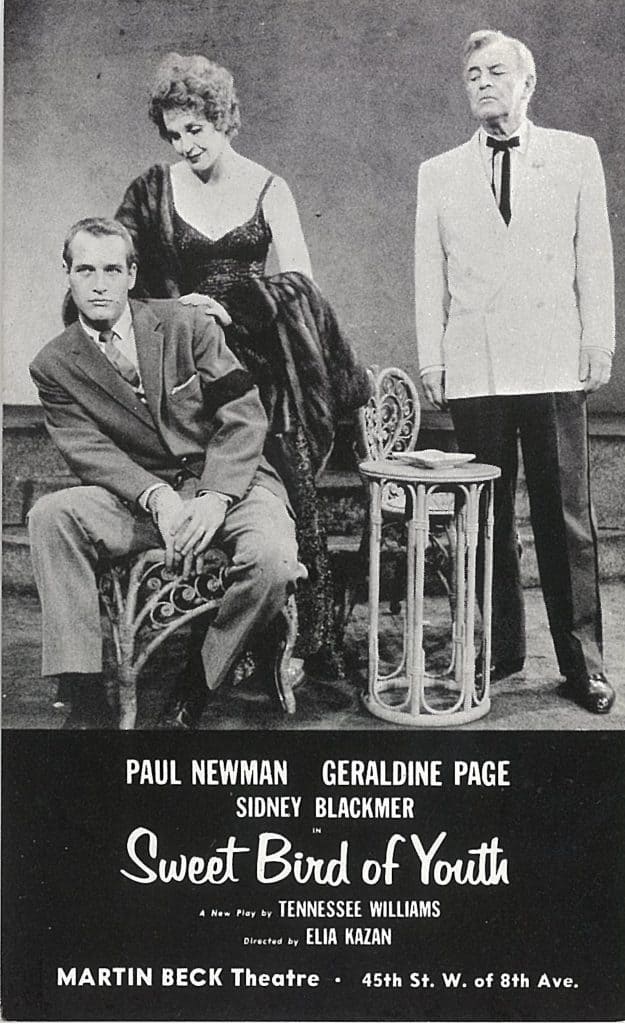

A period landmark was Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller, which played 742 performances following its Broadway opening in February of 1949. It spoke very clearly to the postwar American about the struggle for success and the failure of optimism. A similar theme is expressed in Tennessee Williams’ 1959 Sweet Bird of Youth, which confronts the vain efforts of several over-the-hill actors to remain relevant.

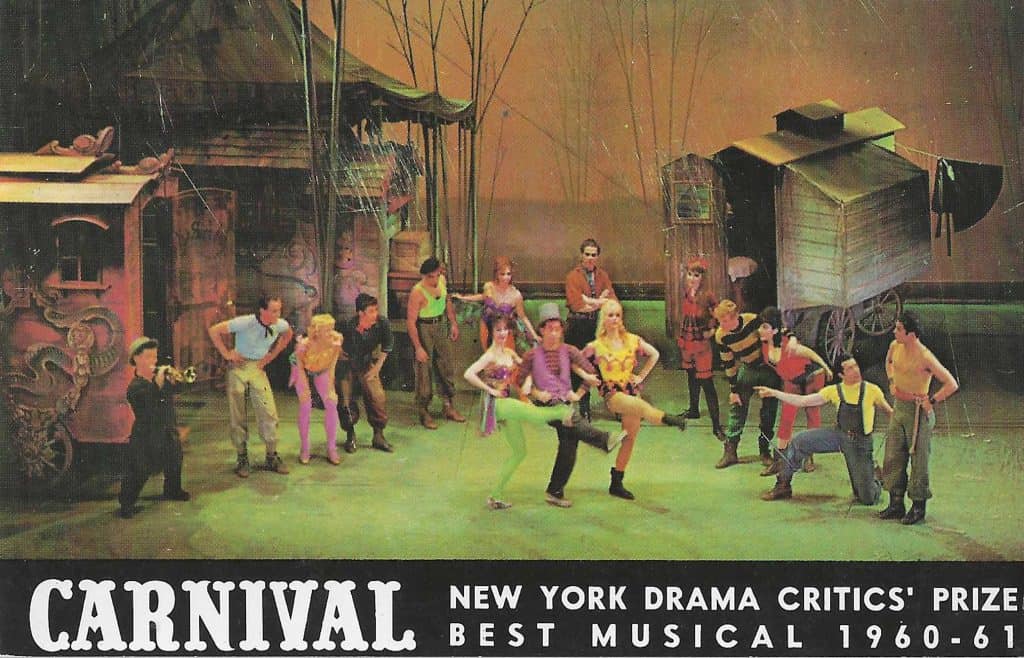

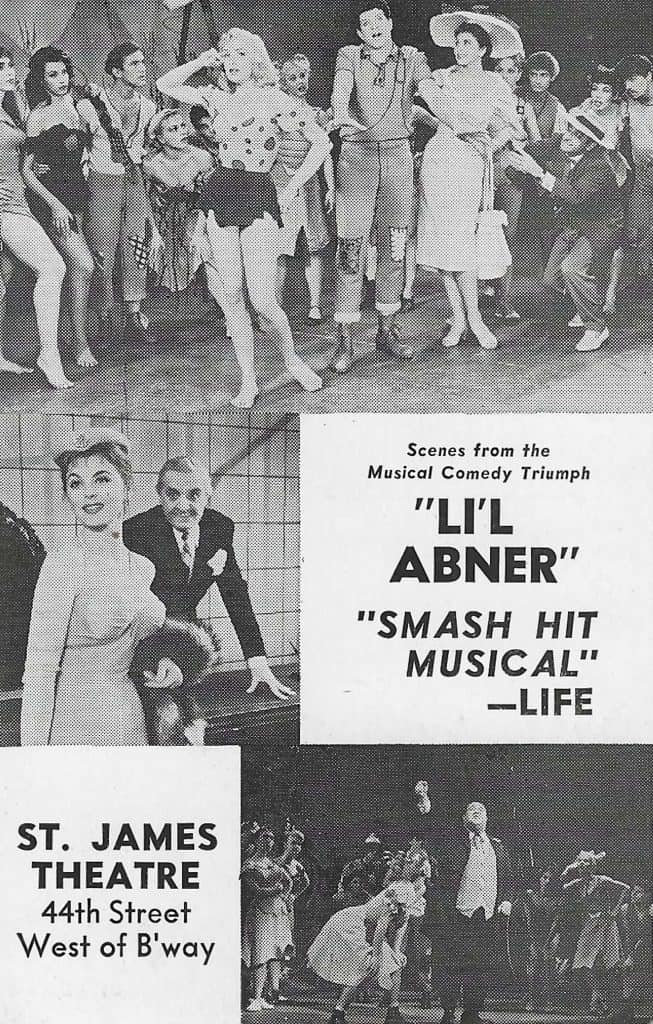

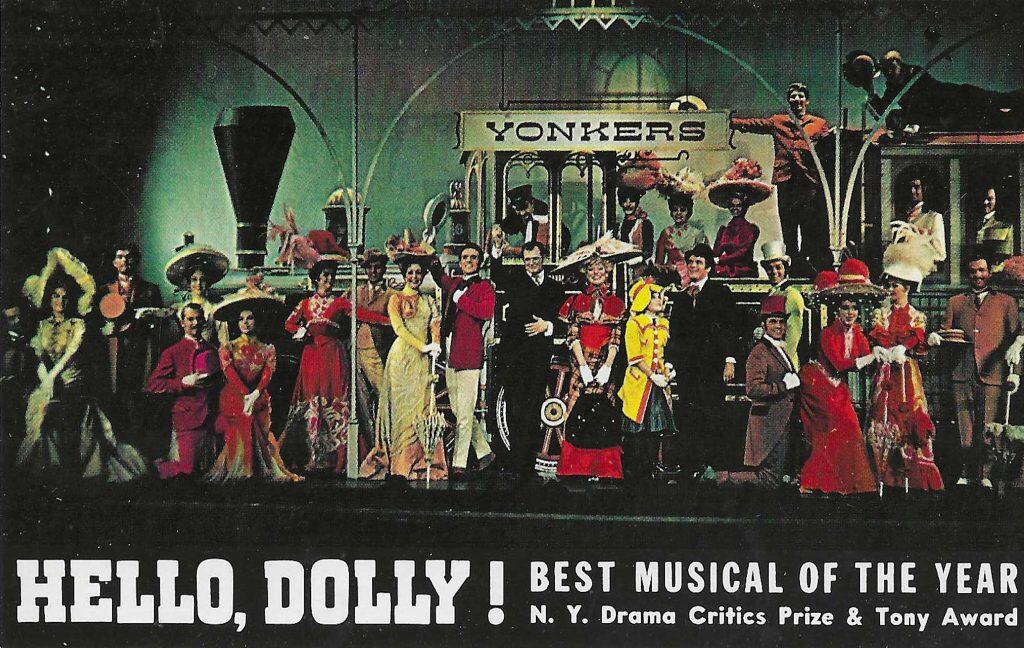

Despite its dramatic successes, like the work of Hellman, Miller, and Williams, what most characterizes Broadway’s interwar and postwar trajectory is the increasing importance of comedies and musicals. As far as postcards are concerned, this movement coincides to some extent with reduced use of postcards as promotional tools. It is difficult to explain this: perhaps it had something to do with reduced marketing budgets. Otherwise, it is possible that audiences saw sending postcards about play attendance as boastful and self-indulgent. For the collector, it indicates a scarcity of top-rated shows gaining recognition on postcards.

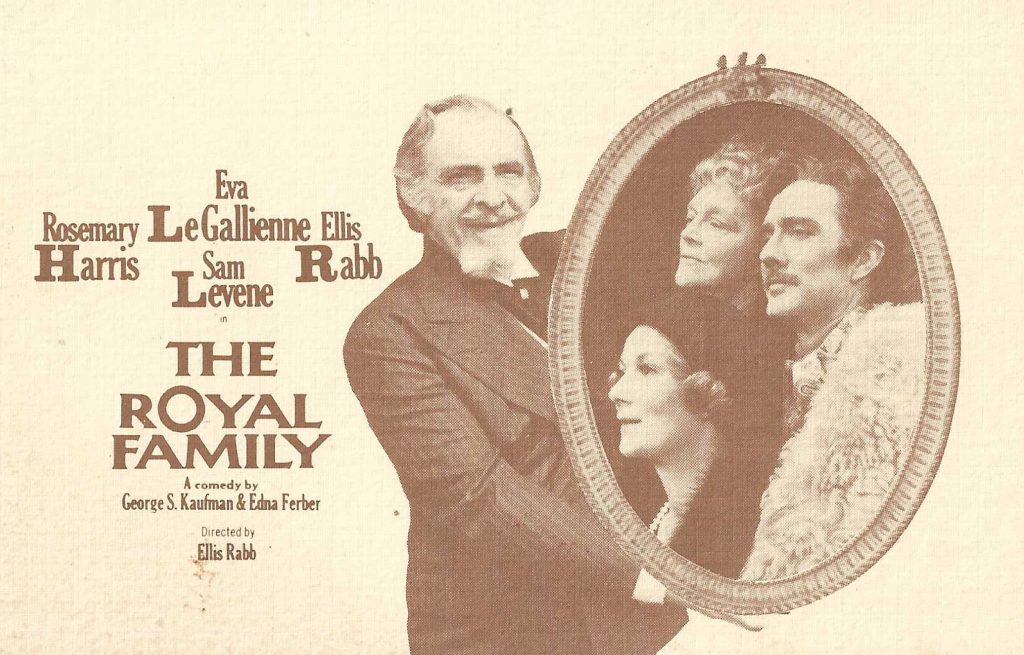

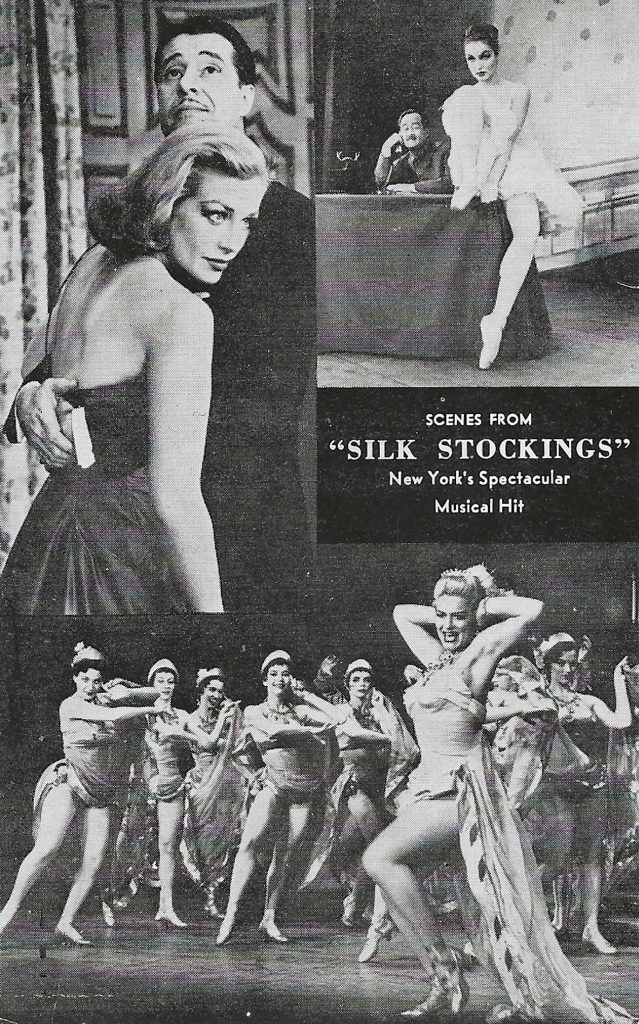

As far as the intersection of comedy and musicals are concerned, it is hard to think of people who merit more acclaim as pioneers than George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber. Equally notable were Cole Porter, Richard Rogers, Lorenz Hart, and Oscar Hammerstein II. Porter’s 1955 musical Silk Stockings benefitted from George Kaufman’s writing. The parody about the theatrical Barrymore clan, The Royal Family, written by Kaufman and Ferber and produced in 1927, is memorialized in this postcard for its 1975-76 revival at the Helen Hayes Theatre. The latter production won a gaggle of awards including a Tony for best direction.

Edna Ferber was the author of Show Boat (1926) whose recreation into a musical by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II and staging in 1927 by Florenz Ziegfeld was one of the most significant transformative moments in the history of American theater. Responsible for standards like “Ol’ Man River,” the show traces the peak and decline of a uniquely American art form, river boat entertainment, from the perspectives of both its stars and service workers. Ferber needs to be acclaimed for basing her work on careful research about the genre, including spending some time making direct observations on an actual show boat based in North Carolina.

Kern and Hammerstein reconceptualized the Broadway musical and advanced it beyond the light operas, operettas, and Follies-type revues that dominated Times Square entertainment. Show Boat was the first “musical play” that took on a serious theme, including social issues like racial prejudice and ethnic assimilation, developed characters and plot and then integrated it all musically.

George S. Kaufman’s recognition as “America’s greatest comic playwright” is attested by his two Pulitzer Prizes and collaborations with the finest American authors, including the Gershwin Brothers, Moss Hart, and Edna Ferber.

If it’s starting to sound as though theater people through the 1920s and into the ‘40s were all part of some tribe or extended family, that perception is correct. The tribal connection was through the Algonquin Hotel Round Table, a hostelry over on 45th Street, where they all lunched together while gossiping and networking. They were all regulars – writers, producers, actors, and critics, Kaufman, Sherwood, Edna Ferber, Alexander Woollcott, Ring Lardner, Tallulah Bankhead, and scores of others.

George Abbott’s 1938 production of Rogers and Hart’s The Boys from Syracuse represents the first comedy by William Shakespeare, The Comedy of Errors, to get re-staged as a Broadway musical. This came complete with a score that used the Swing idiom and left behind memorable standards like “This Can’t Be Love” and “Falling in Love with Love.” Sadly, following his success here, Lorenz Hart became worn down by self-doubt, illness, and alcoholism. Rogers needed a new lyricist and found one in Oscar Hammerstein II. Their collaboration over many years established the canon for the postwar musical and produced numerous classics that continue to get resurrected in revivals.

Rogers and Hammerstein’s premiere work, Oklahoma!, opened in 1943 and was an instant runaway hit with an unprecedented 5-year run and 2,212 performances on Broadway followed by a 5-year national tour. Based on a story about a love triangle in pre-statehood frontier Indian Territory, as Oklahoma was known, it’s not a happy romp of songs strung together with a weak plot. Following Hammerstein’s ideals, the story line and character development are well integrated into the music creating something fresh and surprising. Hits like Carousel, which confronted an antihero and abusive household and South Pacific, which deals with interracial and cross generational relationships followed in 1945 and 1949 respectively giving us a slew of songs that encourage us to move along in our daily lives, like “Oh, what a beautiful morning,” You’ll never walk alone,” and “Some enchanted evening.”

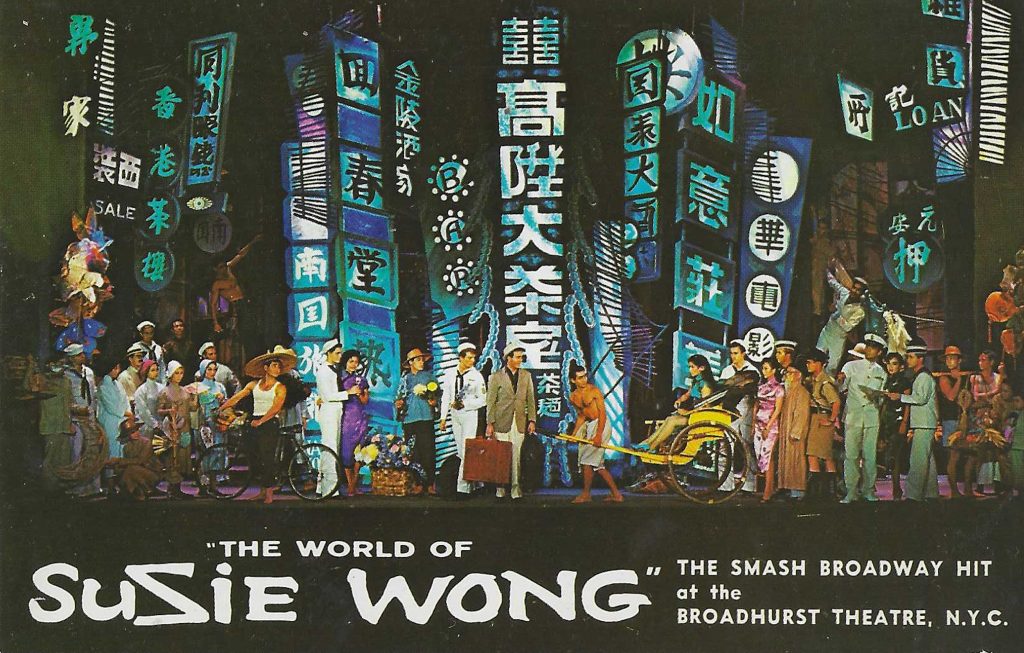

Theater took an ethnic turn into the 1960s. West Side Story opened at the Winter Garden Theater in 1957, with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and music by the immortal Leonard Bernstein and choreography by Jerome Robbins. The musical adapted one more of Shakespeare’s plays, Romeo and Juliet in telling the timeless story about innocent young love and how it can be obliterated by conflicting adults. With the “other side” represented by Puerto Ricans who were deemed to be encroaching on a poor white neighborhood in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, the musical has become a landmark of America’s march toward assimilation of its Latino immigrants with hits such as “Maria,” and “America.”

Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe’s My Fair Lady (1956), a musical adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion handled the question of conflicted love differently. In fact, it showed how love can be ignited and possibly persist despite class and cultural differences. With a tip of the hat to Victorian and Edwardian music hall styles dominant on Broadway nearly a century earlier, My Fair Lady was a runaway hit that made superstars of its premier performers Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews.

Broadway’s longest enduring hit of the 1960s, the first to surpass three-thousand performances was Fiddler on the Roof (1964), based on the stories of Tevye the Milkman by Yiddish Folklorist Sholem Aleichem with music by Jerry Bock and lyrics by Sheldon Harnick. Though set in a traditional nineteenth century eastern European Jewish Village, Tevye suffers the travails of everyman, seeking continuity and respect for tradition in the face of rapid social change – struggling to keep his family together as his children succumb to the opportunities and temptations of the world beyond the Village; dealing with inscrutable and inexplicable prejudice that eventually obliterates his village. Fiddler has been revived constantly since its inception. A favorite of school and community productions, there is hardly a single wedding in America, Jewish or Gentile, where “Sunrise, Sunset” is not played.

Caption: Nostalgic rural and traditional Americana and multicultural ethnic themes predominated in 1940s-1960s Broadway.

Nevertheless, over the late 1960s and into the ‘80s, Broadway seemed to be gasping for breath. The loss of hotels and restaurants combined with theaters crashing down all over the neighborhood as wrecking balls ensnared obsolete movie palaces and legitimate theaters alike. A crime wave took over the theater district with muggers and prostitutes plying their trade in abandoned doorways.

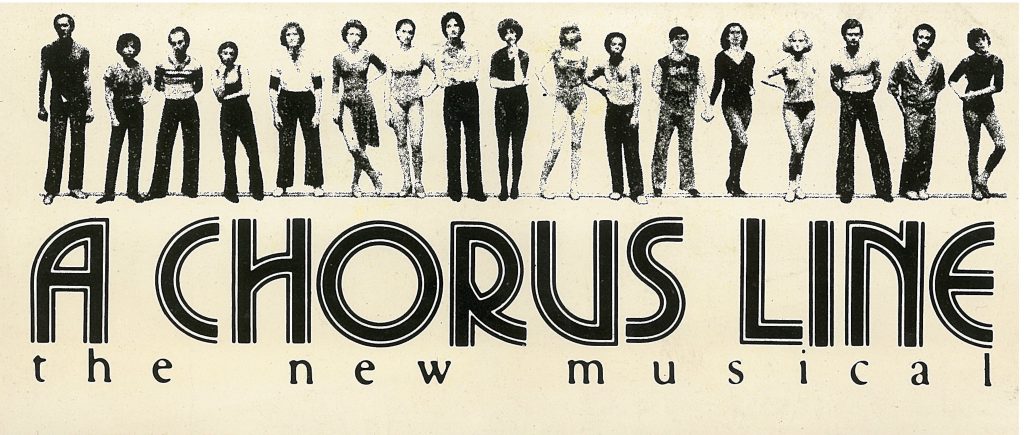

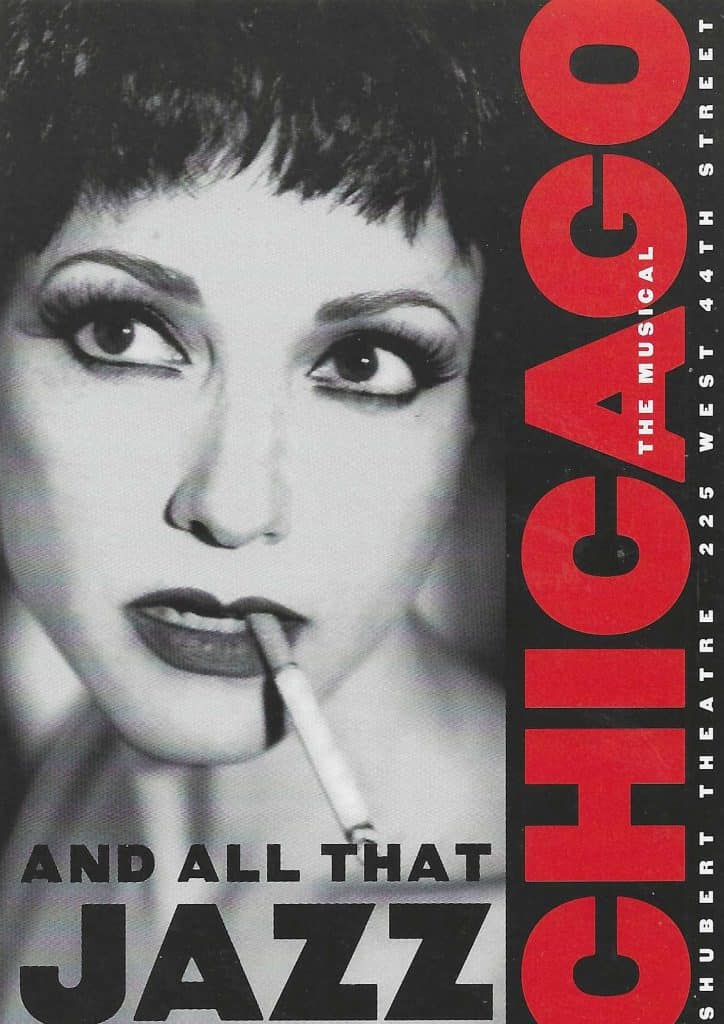

A Chorus Line, the 1975 musical about an audition for a dance company with music by Marvin Hamlisch and lyrics by Edward Klevan seemed like a breath of fresh air. With seventeen dancers vying for a limited number of spots in a chorus line on a bare stage, each one reaches into their character and biography for the resources to compete. In keeping with the Zeitgeist, one of the more sympathetic and revealing characters is a gay man. A Chorus Line ran for a record-shattering 6,137 performances but, more importantly seemed to restore Broadway’s will, verve and excitement.

By the 1980s and 1990s, New Yorkers made a commitment to Broadway and organizations like The New 42nd Street, rose to arrest the decline and restore the theater district. Although their quest seemed somewhat quixotic at first, their efforts paid off with theaters like the New Victory and New Amsterdam being rebuilt and restored. In a most hopeful endeavor, the Disney Company came back to produce live versions of its shows. New types of musicals, the jukebox and dance musical gained popularity and attracted new audiences.

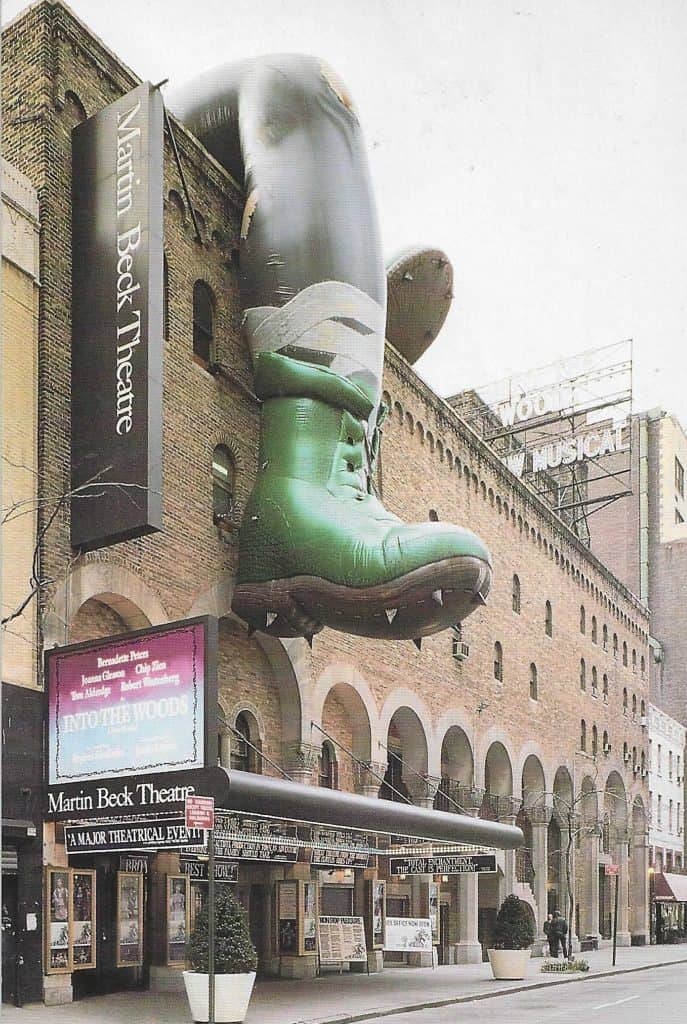

And, then postcards returned as promotional tools for Broadway shows, sometimes sponsored by theaters like the amazing card depicting feet dangling over the Martin Beck Theater to promote Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods or cards published by the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center. Alternatively, publishers of promotional “rack cards” like Max Racks and Go Cards issued striking announcements for new productions. The world was set right again.

You left the best for last. Thanks for the series Hy. I had the pleasure of seeing a few of these classics. I’m looking forward to your next New York project and of course your great postcards.

Thank you for this great summary discussion. I echo Doug’s comment – I am looking forward to your next NY project.

Love this one in particular. These postcards speak volumes of an era filled with glamour, vitality and hope. Not to mention, the naughty factor. Your writing, Hy, is warm and breezy. Sending big hugs.

This article was such fun. Thanks from Adelaide

When my family visited New York in 1966, my mother’s parents (who were living in Manhattan at the time) gave Mom and Dad tickets to see Pat Hingle and Eddie Bracken in The Odd Couple. The seats cost six dollars each, a princely sum at the time!