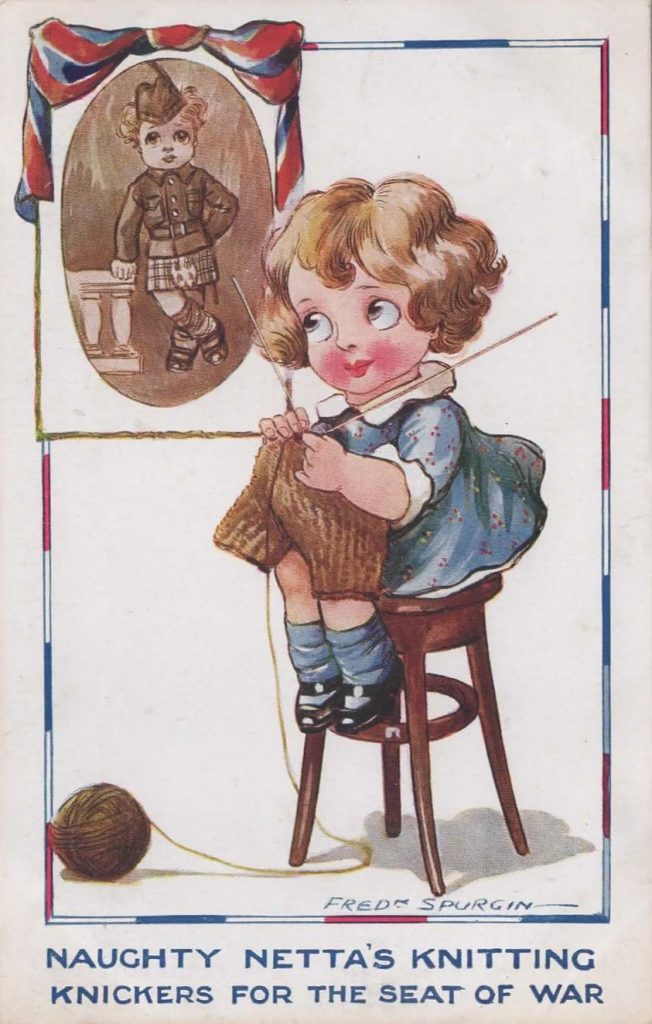

“Naughty Netta’s Knitting Knickers for the Seat of War.”

This postcard has a great piece of alliteration as a title and a well-drawn illustration by Fred Spurgin. Its initial appeal is the inclusion of the inset child-like Scottish soldier, although a Scottish kilt wearer is allegedly the least needy of new undergarments.

With such a divine face it is hard to imagine what was “naughty” about Netta, although perhaps we could agree that ‘Nice Netta’s Knitting’ probably wouldn’t result in as many card sales since we humans tend to like a suggestion of vulgarity in our humor.

This postcard was mailed between correspondents in New Cross in southeast London on April 29, 1914, and was used by “Wal” to wish Miss Ethel Phipps of Egmont Street many happy returns, although Wal also writes I hope you will like this card. Whether Ethel did or did not like the card is impossible to know, but it could certainly be liked enough to be added to a World War One postcard collection.

Ethel Emily Phipps can be found at the above address in the 1911 Census when she was then a 21-year-old book folder and sewer for a printer. She was the oldest of the three surviving children of William D. Phipps, a self-employed master baker, and his wife Elizabeth.

In November 1916 Ethel married a Royal Navy petty officer, Thomas Walter Thorn. They both survived the war and lived out their lives on the Isle of Wight. Thomas Walter Thorn may well have been ‘Wal’ who sent the message with love.

It is common knowledge that women on the home front knitted ‘comforts’ for the soldiers although this card set me wondering how formal such arrangements were.

It can be found on the website of The Cheltenham Trust that “In 1914, the War Office was faced with the herculean task of clothing a volunteer army of unprecedented size. Each man was issued with a basic khaki field service uniform consisting of greatcoat, trousers, tunics, flannel shirts, drawers, vests, and three pairs of socks. More pairs of socks were to be issued every three months. Given that soldiers would need to carry out long marches, and that as winter approached trench warfare would be cold, wet, and muddy, it was obvious that these supplies were essential.

On August 29, 1914, Lady French, the wife of General Sir John French, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, set up a campaign to provide ‘comforts.’ She wrote in The Times (of London) “There is a great need for knitted socks for our troops…. I would ask those who have leisure to knit, or are willing to employ others to do so, to send parcels as soon as possible.”

On the same website there is: “Women responded with a tsunami of knitted goods. Knitting clubs were set up in every town and village; social rules were relaxed to allow knitting on buses, in queues, at shops, at the theatre, even at dinner parties and between courses at restaurants. Children were taught to knit from a very young age, and everyone from the elderly and infirm to wounded soldiers in hospitals was set to work winding wool into balls from skeins, making garments or packing the ‘comforts’ to send overseas. These homemade gifts not only provided warmth but raised morale at home and on the front.”

This Times account is fine, but it was nice to learn that Lady French was not the only influence in this knitting craze. And too, that knitting for the troops was not a new phenomenon, as knitted ‘comforts’ were provided to the troops fighting in the Boer War (1899 to 1902 in South Africa). It did not seem relevant to research older accounts, although given that knitting is an ancient craft, it may be safe to assume that troops fighting in the Crimean War (1853 to 1856) and Napoleonic Wars (a series of conflicts fought between 1803 and 1815) also benefitted from woolen goods, and perhaps this occurred for centuries before.

World War One started on July 28, 1914, and there is evidence that the first requests for woolens for the troops came as early as August 8, 1914, in the Kentish Express, in the form of a letter to the editor that read in part:

Sir – May I make an appeal through your columns to those who are willing to work for our soldiers and sailors during the coming war? There is sure to be a great need for garments of various kinds for the men in the hospitals, and I shall be glad to supply the most approved patterns of these both for materials and wools to any who will write for them and enclosing a penny stamp. The following is a list of garments which were of greatest service during the Boer [War] which are always in constant demand; – Flannel. – Men’s shirts, bed jackets in natural colors or scarlet vests, chest protectors. Wool. – Thick knitted socks (No.12 needles to be used), chest protectors, cholera belts, bed socks. In addition to these, soft slippers, waistcoats, and mufflers are useful and can be made if preferred. – Yours faithfully, ETHEL FORD.

Also found are references to both the ‘Queen Mary Movement’ and ‘Queen Mary’s Appeal.’ These terms refer to “The Queen Mother’s Clothing Guild, that was established in 1882 when the matron of an orphanage in Dorset asked Lady Wolverton for 24 pairs of knitted socks and 12 jerseys for the children in her care.

The queen started a small guild amongst her friends to provide not less than two garments for each child at the orphanage and to supply clothing for other charitable institutions. The guild grew quickly and by 1894 the London Needlework Guild was making and distributing over 52,000 garments a year.

In 1885 Princess Mary Adelaide of Teck, mother of the future Queen Mary, had become patron of the London guild and began an unbroken line of royal patronage. In 1897 her daughter, the Duchess of York, the future Queen Mary, became the patron, having helped her mother with the charity since childhood.

On becoming Queen Consort in 1910, Queen Mary renamed the charity, the Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild, and in 1914 declared the Saint James Palace as its headquarters.

During World War One the guild sent over 15.5 million articles of clothing and surgical items (estimated value, in excess of £1 million, to troops overseas. The guild also provided much needed help to women and their families at home through donations to hospitals and parishes.

From 1914 the officials of Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild wore round burgundy and gilt enamel badges with Queen Mary’s Royal Standard. The regular volunteer workers wore Tudor Rose enamel badges, sometimes with a blue ribbon and bars denoting the years worked during the first world war.

So, Naughty Netta’s knitting needles helped the war effort considerably, although it would be nice to say, that she used only the softest wool for the undergarments.

Besides being more bawdy than its “Nice Netta” counterpart, “Naughty Netta’s knitting” also features three consecutive bisyllabic words that each contain an “n” sound quickly followed by a “t” sound.

Very Interesting!

Wonderful contribution!