Scowling countenance, furrowed brows, lower lip stuck out defiantly, and cigar clenched tightly between his teeth—that is how the world pictures Sir Winston Churchill. He personified Britain’s inflexible determination to resist Nazi Germany, and these very characteristics made him a valuable propaganda asset during the Second World War.

Many people are aware of Churchill’s image on war posters, but postcards also played a part in the war effort. They were a cheap, easily circulated, and effective medium for propaganda. In the period before television and mass communications, they frequently promoted or commented on a wide variety of issues and public figures. Today, historians as well as collectors value them for the insights they give to daily life in a bygone era.

As was done during the Great War, all combatant nations during World War II utilized postcards to promote patriotism. British publishers used many themes: aircraft, ships, and other equipment; humorous samples of life in the military; sentimental and humorous life at home; and prominent personalities. Among cards featuring personalities, more represented Churchill than any other person, far surpassing by a wide margin, the number published of George VI and family and other military leaders. This cannot have been an accident. Many bear the inscription, “Published by Permission of the Prime Minister.”

A fair assumption would be, the numbers indicate that the government, with Churchill’s consent, made a conscious decision to use postcards to make Churchill a symbol of Britain’s defiance. They fostered the development of a personality cult centered around Churchill that promoted his position as prime minister and then reinforced specific values throughout the war.

Churchill became prime minister on May 10, 1940, following the German invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. Those were dark days for Britain. After a decade of poverty, unemployment, and appeasement, morale was low and people were disillusioned. Crisis followed crisis and after the surrender of France on June 25, 1940, Britain stood alone against Hitler’s might. For the first time since the Napoleonic wars, it faced the threat of invasion. Few well-informed people anywhere genuinely believed that Britain could withstand Germany.

Today, Churchill’s wartime image has overshadowed his weak position in May 1940. Expediency, not political strength nor popularity brought him to power. His years in the wilderness had left him with few backers and no power base. Today we dwell on Churchill’s vitality, but in 1940 many in Parliament saw him as a has-been who could not be trusted. Some remembered the charges of incompetence leveled against him after the disaster of Gallipoli in World War I. Others commented on his political instability during the 1930s when his unpopular positions on issues, especially on the dangers of pacifism and a rearmed Germany, had made him a pariah to both major political parties. Some members of Parliament suggested that at age 67 he was senile. Few predicted that he would be able to do more than preside over a caretaker government.

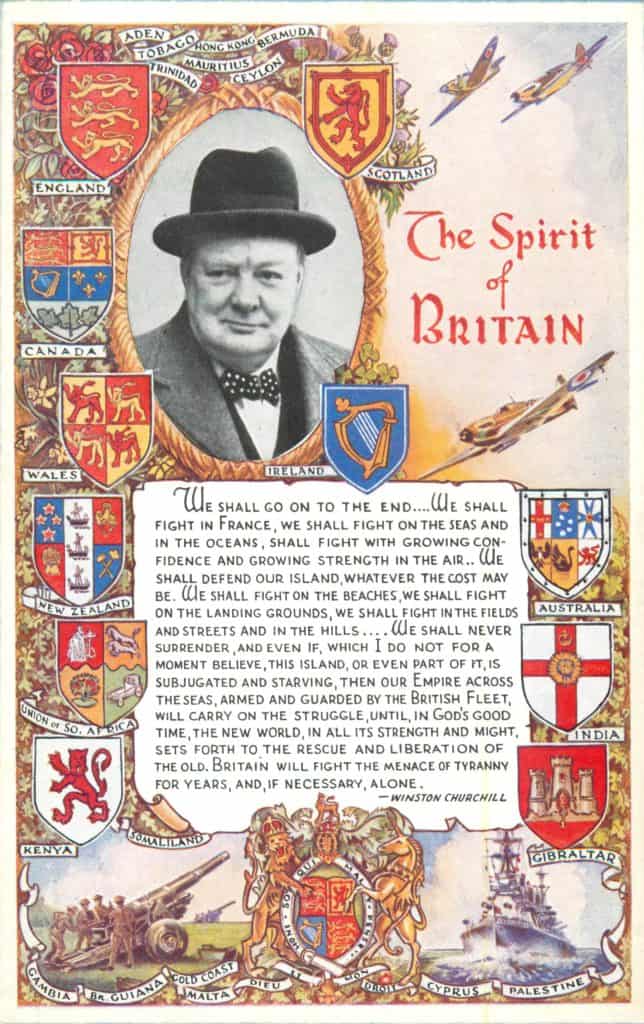

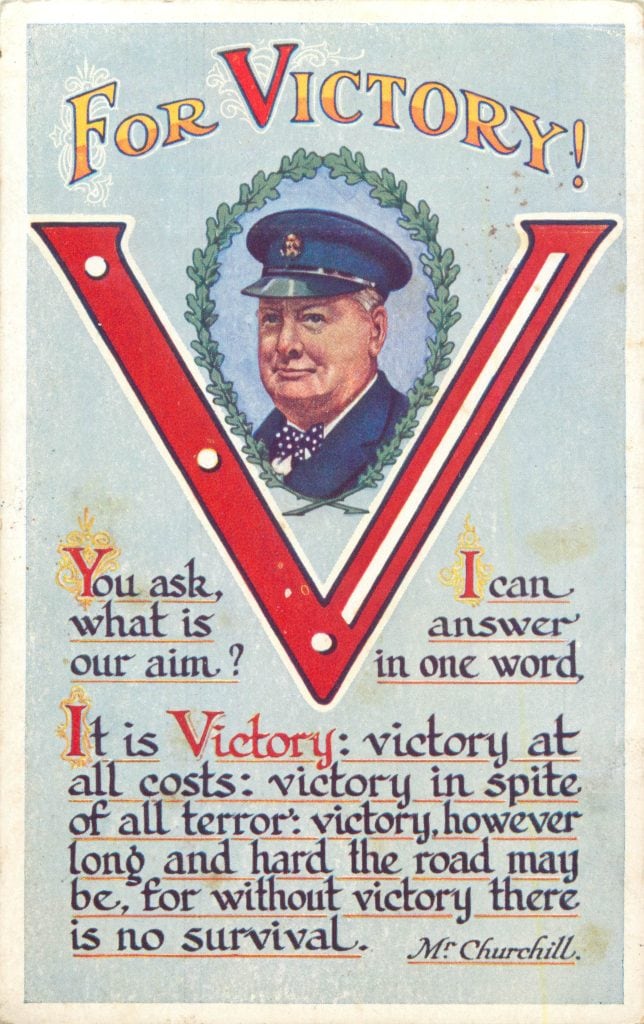

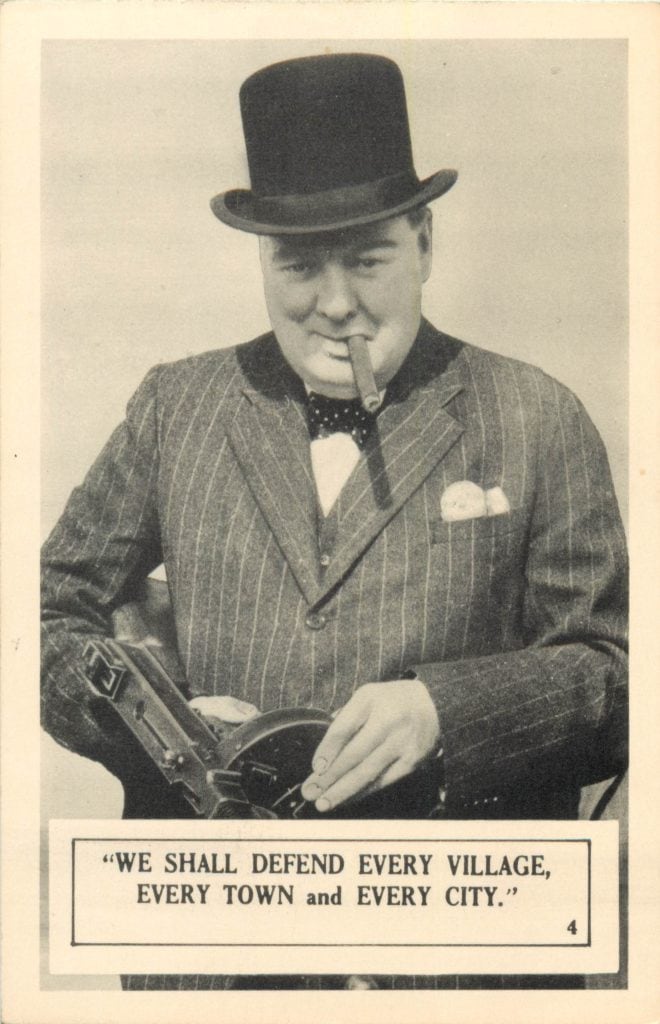

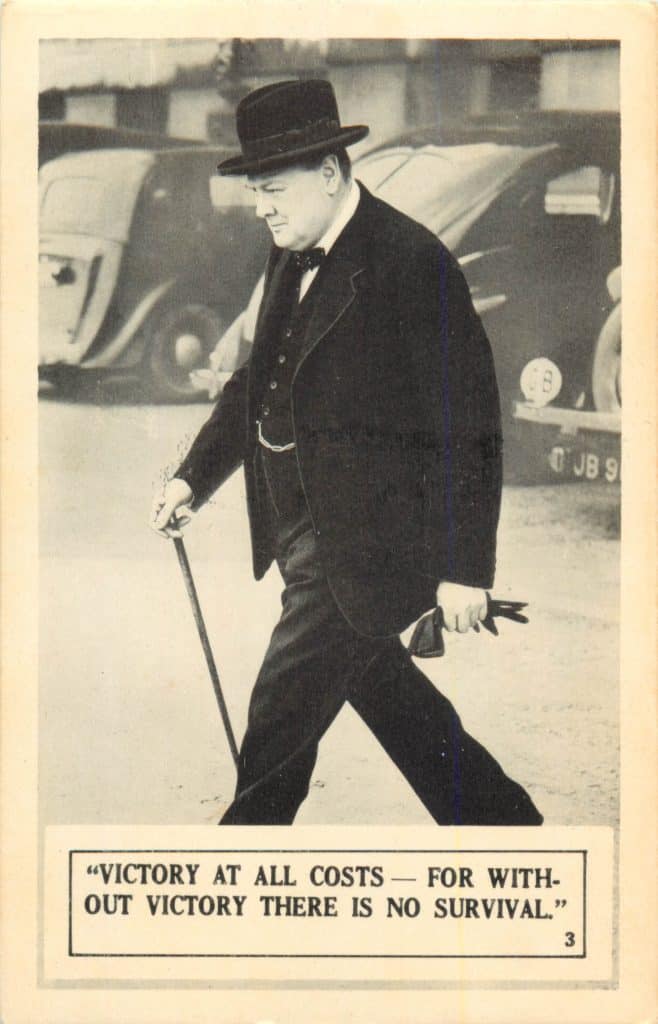

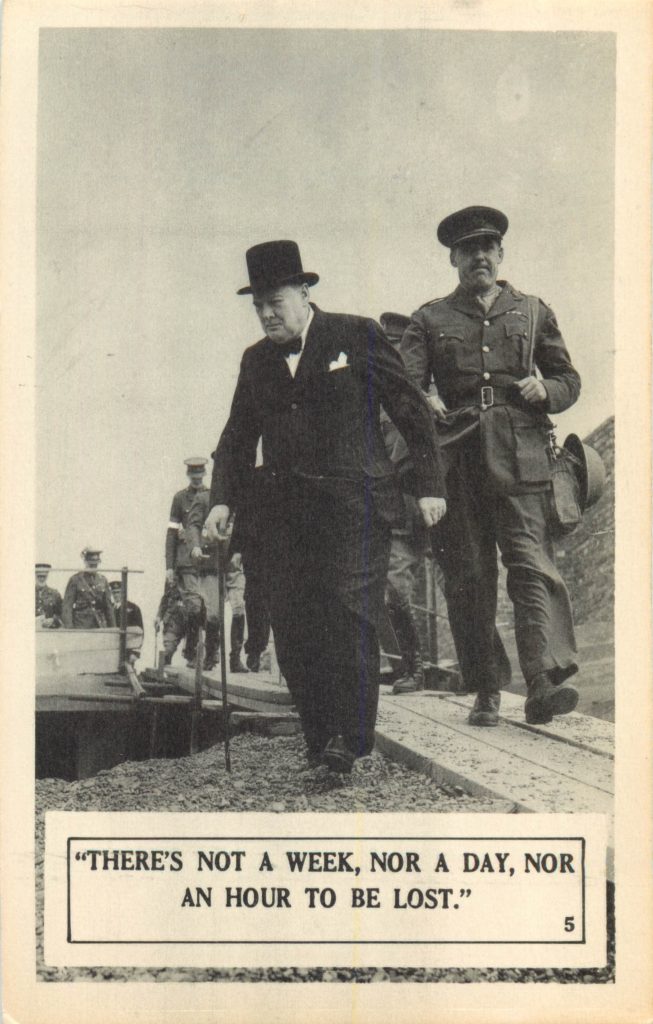

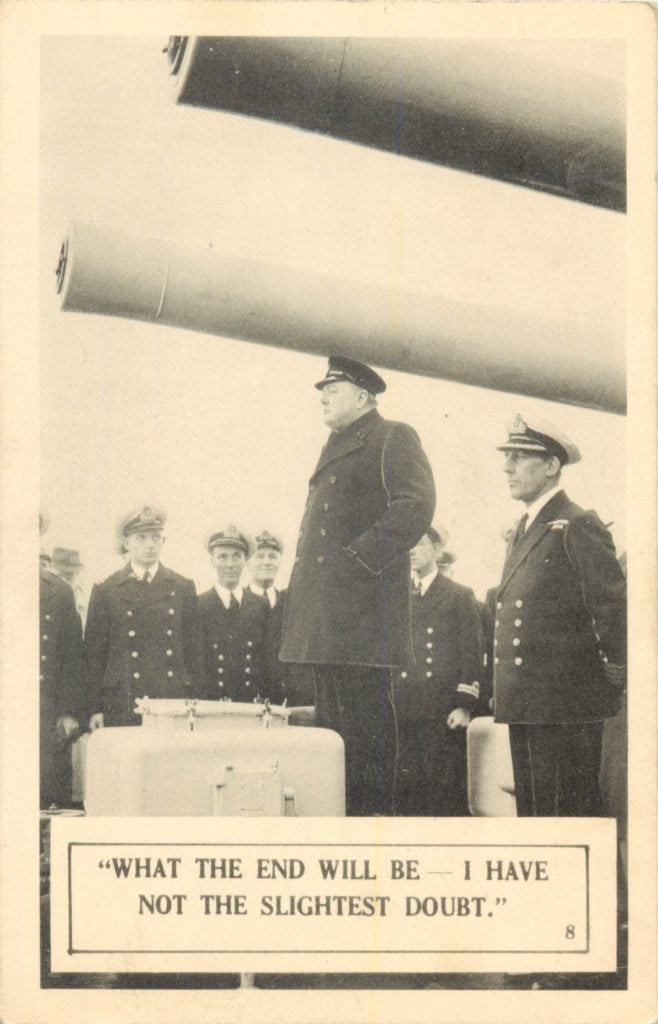

Consequently, not only did Churchill have to direct a war against Germany, he also had to dispel his previous image and win the support of a reluctant Parliament, many skeptical military chiefs, and a despondent people. Perhaps Churchill’s greatest achievement was that he persuaded these groups that only he could save the country from disaster. His own sense of power and destiny fostered this belief; postcards assisted in the transformation. He looked and behaved like somebody important. His propensity for unusual hats, the cigar, and the V-sign were all foibles that drew attention and were easily portrayed on postcards. A typical card from 1940 bears Churchill’s portrait and a quote with the caption “The Premier’s Challenge.” Another one was captioned “The Spirit of Britain.” Each card pictures him either smiling confidently or displaying grim determination. After 1941, he was sometimes shown with Roosevelt and Stalin, emphasizing that Great Britain was no longer fighting alone.

Churchill was a master of the English language and a superb broadcaster. He used his defiant rhetoric to inspire and stiffen British resolve, selecting the right word for the moment. After Dunkirk, to the delight of the British, Churchill used radio to tell the world that Britain “shall not flag or foil. We shall go on to the end…. We shall never surrender.” These were the type of words that people needed to hear. In speech after speech, employing a pattern of exhortation, optimism, and defiance, Churchill rallied his people. Even during the worst of the German bombing raids, Churchill portrayed unflagging confidence: “I feel as sure as the sun will rise tomorrow that we shall be victorious.”

Postcards bearing quotes from his speeches reinforced the mood he wanted to foster. Many quotes were coupled with his photo, but sometimes a postcard would feature George VI or a general with a Churchill quote on the message side. One of the most dramatic was a card showing St. Paul’s Cathedral against a background of London burning, with Churchill’s defiant words on the reverse. Even children’s greeting cards, with no apparent war theme, sometimes featured quotes from Churchill on the message side.

Churchill refused to leave London during the blitz, and he took every opportunity to visit factories, airfields, bomb-ruined houses, and the battle front, often putting himself in danger. Some saw this as his insatiable romanticism, but his bravery, mixed with a touch of bravado, helps explain why he was respected by the military and revered by the people.

When millions of non-combatants endured an ordeal of fire on a scale hitherto unknown, he was seen to share their peril. Morale soared as a result. Again, postcards reinforced Churchill’s image.

One card pictured him with a machine gun and the quote, “We shall defend every village, every town and every city.” Others portray him pouring over maps with his generals. Some showed him visiting London’s beleaguered citizens or “in the battle line” wearing a helmet. His visit to a London air raid shelter that had taken a direct hit shows the success of this propaganda effort. His visit brought cheers of “Good old Winnie,” and “We thought you’d come and see us,” and “We can take it; give it ’em back” Churchill broke down. An aide heard an old woman say, “He really cares; he’s crying.” American journalist Ralph Ingersoll reported in November 1940, “Everywhere I went in London people admired his energy, his courage, his singleness of purpose. People said they didn’t know what Britain would do without him.

Churchill not only made himself the symbol of Britain, he also made himself the symbol of people in countries occupied by Germany. He often broadcast directly to them; they listened, even though they were subjected to harsh punishment if discovered by the Nazis. It was his image that came to represent the hope of a return to freedom.

Postcards featuring Churchill were published clandestinely in at least the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. Some were identical to those published in Britain, except on much thinner stock. One French Easter card, probably from 1945, shows a little cluck giving Churchill’s famous “V” sign while riding in a tank made from Easter eggs.

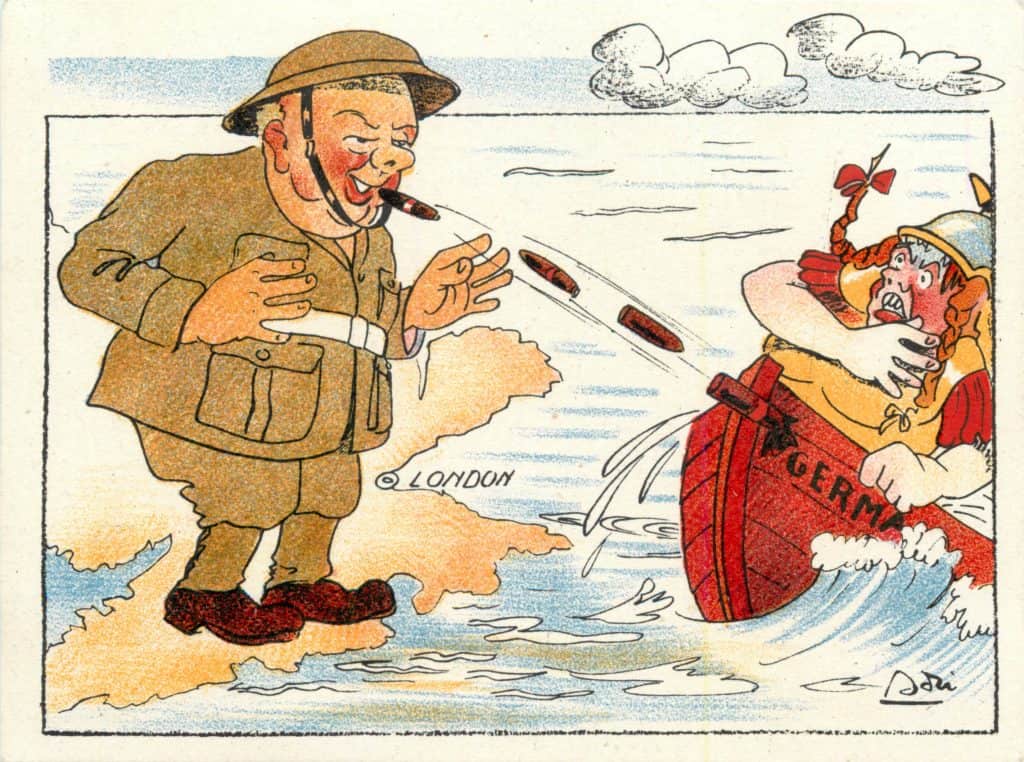

Although it is hard to quantify, postcards bearing Churchill’s likeness undoubtedly played a part in winning the war. They helped reshape his public image in Britain and abroad in the critical months of 1940 and reinforced this image in subsequent years. The fact that the Germans published anti-Churchill postcards of their own to counteract his personality cult indicates their influence.

Today, when seen individually, the Churchill cards are small reminders of the war years, but when viewed as a group, their collective message becomes more evident, and their influence was probably larger than most people realize. Their availability, size, and variety had to make them popular. Certainly, they were popular enough to have survived to give collectors and historians an idea of how Churchill wanted to be perceived: as the personification of Britain’s inflexible determination to resist, and ultimately triumph over Nazi Germany.

Excellent article!

Thanks Tom for an interesting story of Churchill.

When I was in first grade, our teacher was looking at the stamps my classmates and I had brought in so that our report cards could be mailed to our parents. My dad had given me a stamp depicting Churchill, and the teacher explained to the class that Winston “was a famous man who died in England about a year ago.” The truth, but certainly nothing approaching the whole truth..

Fascinating article. I did not realize, although it sure makes sense, the Nazi’s published postcards beating up on Churchill. Thank you for this article.

Great article Tom! Thanks for the history lesson!