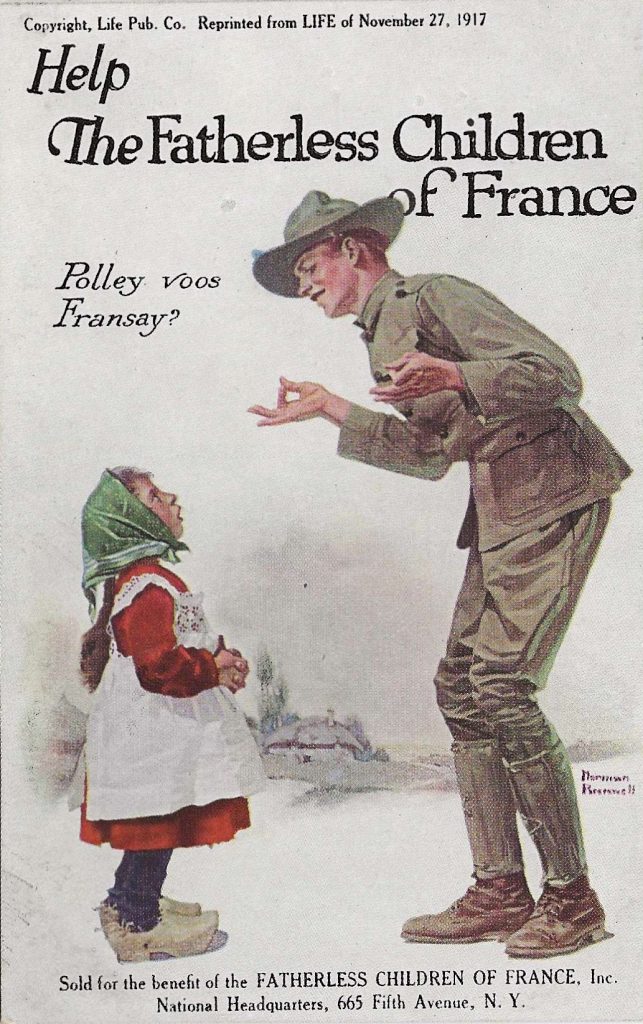

The research is incomplete because it is unknown who commissioned Norman Rockwell to create this adorable image of a tall American soldier trying to speak to a little girl. There is a copyright that clearly suggests it was Life Publishing Company. That could be but the second half of that line is a “reprint statement” that tells us the image was reprinted from LIFE of November 27, 1917, which is incorrect – this image appeared on the cover of LIFE on November 22, 1917. One week earlier.

It seems that the soldier is asking if she can speak French, by saying, “Polley voos Fransay?” which is certainly an American’s distortion of “Parlez-vous français?” The question may have been best asked, “Parlez-vous allemande?” (Dutch) since it is quite obvious from the clothing (wooden shoes and white play-apron) the girl is wearing that she is Dutch, not French.

At the bottom, one additional bit of text states that the sale of the card will benefit the Fatherless Children of France, Inc. A national headquarters address is included.

[Rockwell, himself, titled his painting, but after subsequent uses the image was given an alternate title for unknown reasons. It became Soldier Speaking to Little French Girl, which perpetuated what this writer considers an error.]

The Fatherless Children of France, Inc. was a charitable organization based in New York City in a building that was demolished circa 1922 to make way for the Jensen Department Store (the Jensn structure, in the 1970s, became the Rolex Building). It was on the southeast corner of 5th Avenue and 53rd Street during World War One that FCF began gathering financial assistance and material support for the children of French soldiers who had lost their lives in the conflict. The impact of World War One on France was devastating, with millions of lives lost and countless families shattered. The children from those families faced an uncertain future, and thankfully the problem was recognized and delt with before the inevitable social collapse happened.

Most of the donations and fundraising events were pointed toward educational support and emotional care. And it was admirable that the FCF worked closely with French authorities to identify and assist those most in need.

The vast majority of the French and Dutch children who were aided by FCF funds are gone now, but their descendants still appreciate the help their parents received that gave them the chance to rebuild their lives and fulfill their potential. Those people are now the senior citizens of their nations.

Fatherless Children of France was not the only support organization that came to the aid of French orphans. In America, the Red Cross and Salvation Army provided food and services that FCF could not manage. In the United Kingdom, similar organizations were established to raise money that brought tons of life-saving provisions across the Atlantic.

***

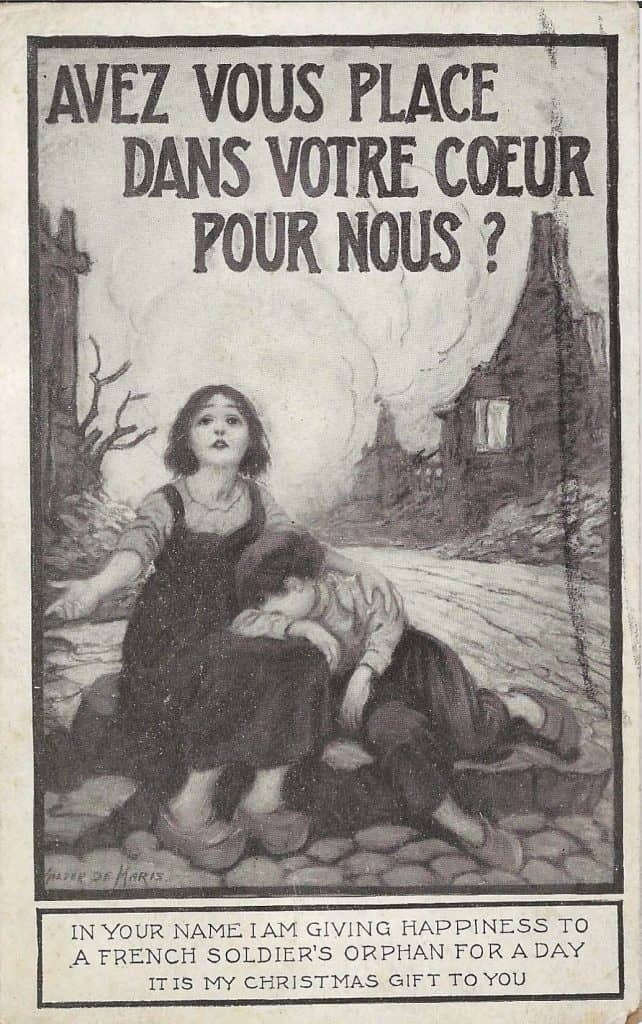

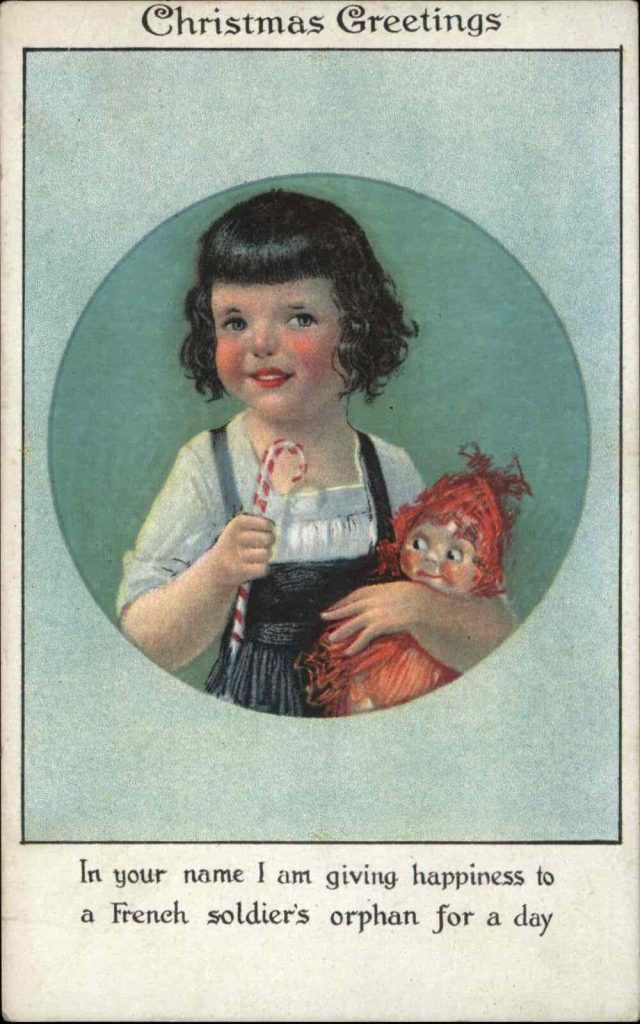

There is no way to learn how many postcards the Fatherless Children group made during the years of 1914 to 1917. One interesting concept that developed within the financial campaigns and fund-raising events put on by the FCF groups was giving a donation to the campaign but telling a friend, relative or co-worker that the donation was “my Christmas present to you.”

The artwork on many of the cards remained unsigned, but this card is signed by Jasper de Maris. The title is in French translates as, Do you have room in your heart for us?

The tagline at the bottom is quite a statement for two reasons: 1. The charity group was so well managed that a day’s worth of food and care per child was economized at seventeen cents. 2. The idea of giving money to a charity in someone else’s name got a lot of people off the hook at Christmas time.

At the same time, there were also dozens of charity centers in Paris and the smaller cities in Belgium and Holland, doing similar work. Most were legitimate and worthy, but others, not so much.

This card is one from a service organization called “Journee du Poilu” in Paris that was organized to assist the French soldier. Cards such as these were made and distributed to children who would sell them on the street as a kind of lottery. Often the children were dressed in rag-tag clothes that would encourage generous donations.

The artwork in this case is that of Francisque Poulbot who did thousands of popular images on posters, postcards, and stamps. He was a lifelong resident of Paris. He died in September 1946 at age 67 and is buried in the world-famous Montmartre Cemetery.

How the lottery was paid has remained a mystery. The call for donations is written at the bottom of the illustration, Pour que papa vienne en permission, s’il vous plait (So that Dad can come ‘home’ on leave, please.)

This was 1915. Remember the year before this was when the men from the First Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers played a soccer match against the 371st German Army Battalion on Christmas Day. (FYI: the Germans won 2 to 1.) The “army brass” ordered that similar events would never happen again, so new ways for kids to see their dads needed to be explored. Merry Christmas.

Always interesting articles!

Shoe styles don’t suddenly stop at the border. Don’t millions of Americans wear Japanese zori in the summer?

Wooden shoes were commonly worn in France back in the day especially in rural areas. The French call their wooden shoes sabots. The practice of making clogs is sabotage and a clog-maker is a sabotier. Probably few French people are seen wearing wooden shoes now because more comfortable leather and plastic clogs are commercially available.

Great article. Interesting how we think everything is “new” yet look at the united effort in the beginning of the 20th century. No email, texts, and minimal telephones yet this across the ocean effort was initiated.

My parents’ former landlady would annually send them a Christmas card which announced that a donation had been made to the Franciscan Friars in our family’s name.

See this link for a history of the organization:https://muse.jhu.edu/article/871336