Some thoughts on collecting cards that feature ethnic, tribal, native and local customs from around the world.

There are many names for postcards that depict native people throughout the world displaying their costumes and enacting their local customs. They are sometimes called “ethnic,” “ethnographic,” “tribal,” or “native.” All these terms seem partially correct but do not quite convey the right meaning. “Cultures” or “cultural” is a more precise and neutral term for describing this postcard collecting category because it is the most comprehensive concept available.

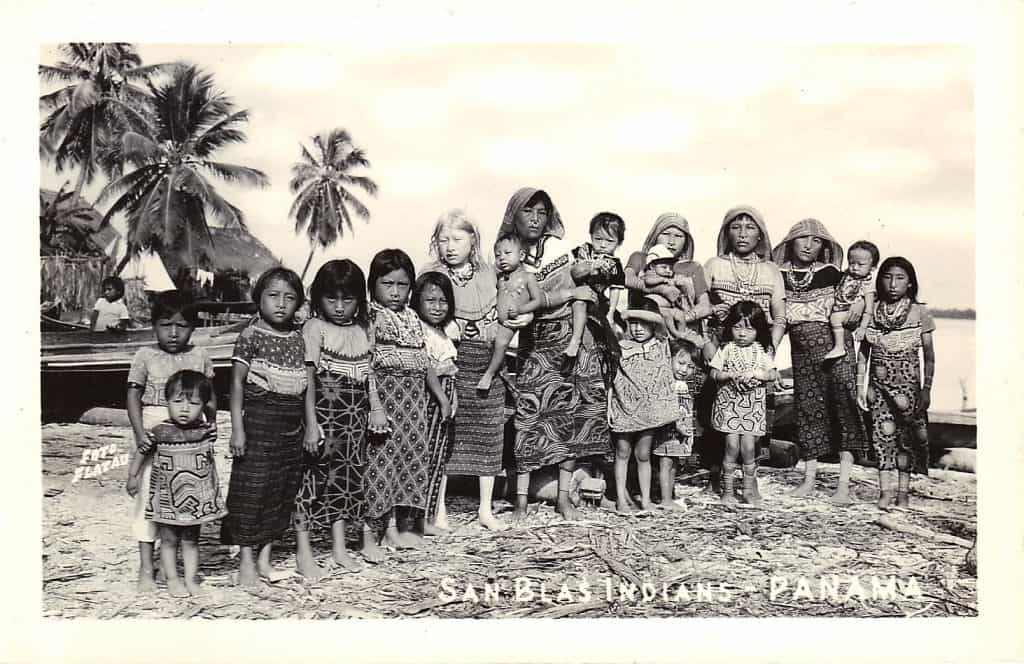

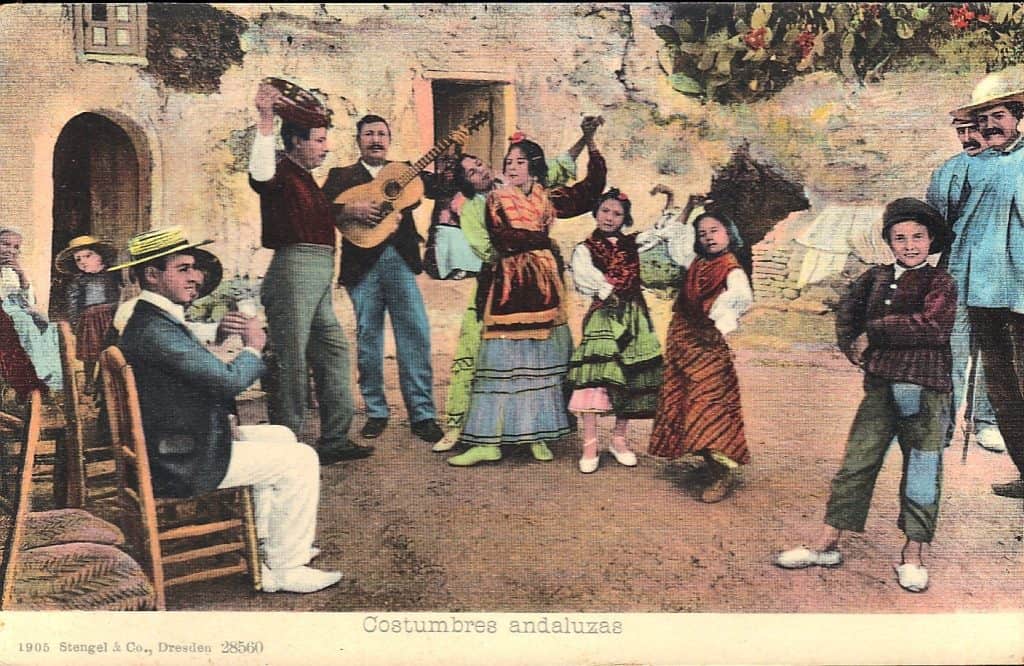

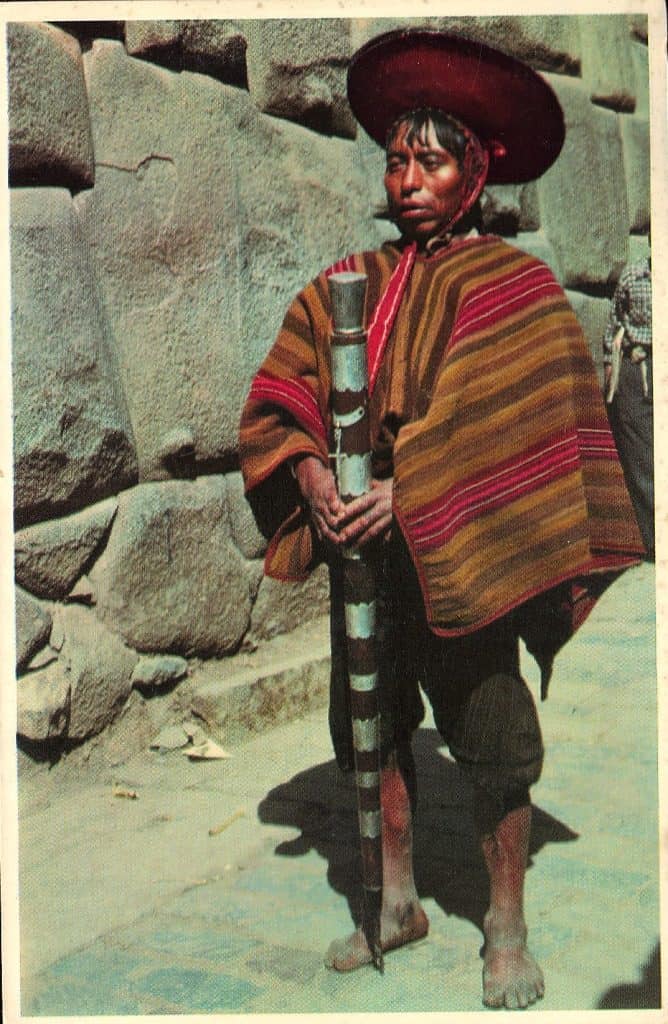

Just as postcards preserve the architectural details of an early 19th century village or a 1950s roadside, they also preserve many particulars of the local culture. Postcards are indeed a catalog of human diversity – cultural differences that exist on a tribal, regional, ethnic, local or national level.

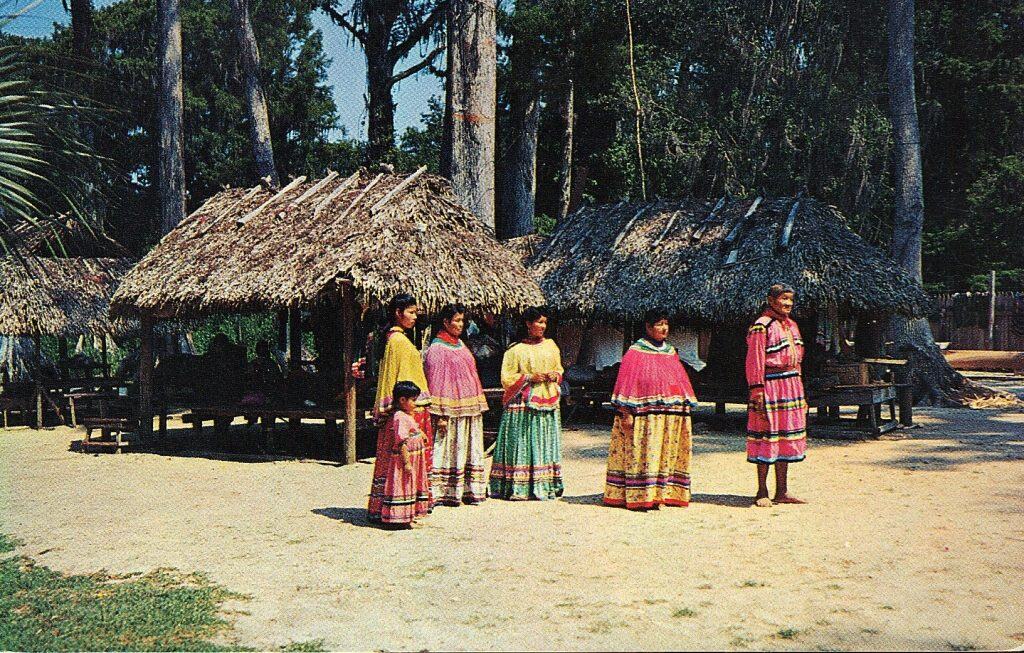

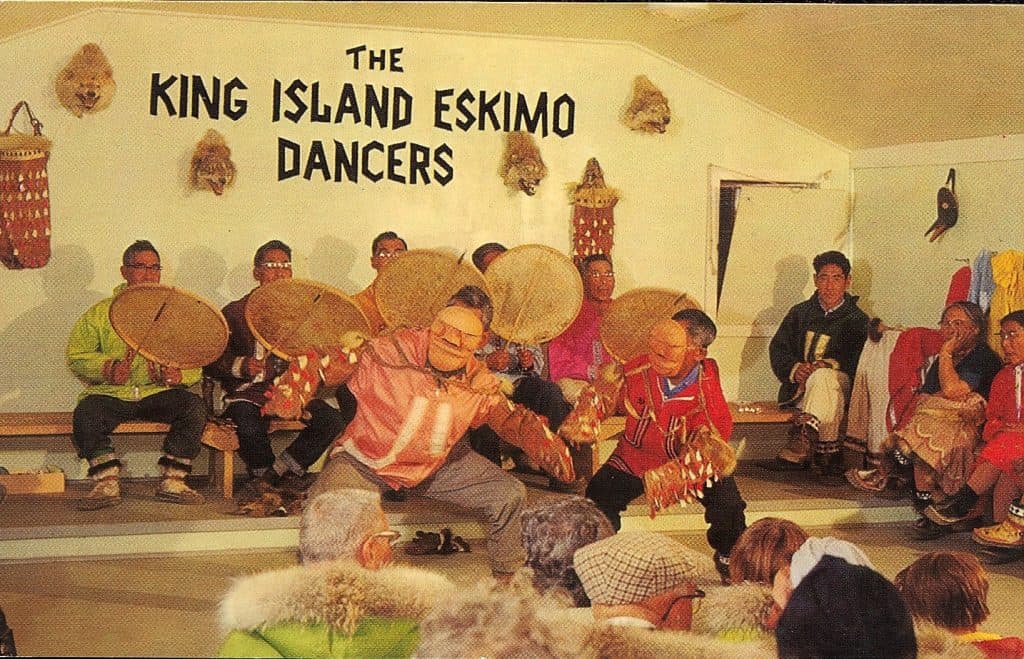

Cultural cards come from everywhere. The cards can represent groups that are Western and Non-Western. In some cases, cultural postcards represent minorities or the indigenous members of a nation; in others, they are of a predominant culture. Some cards depict clothing styles and cultural norms that are long gone; in others these artifacts and behaviors are kept alive as cherished traditions.

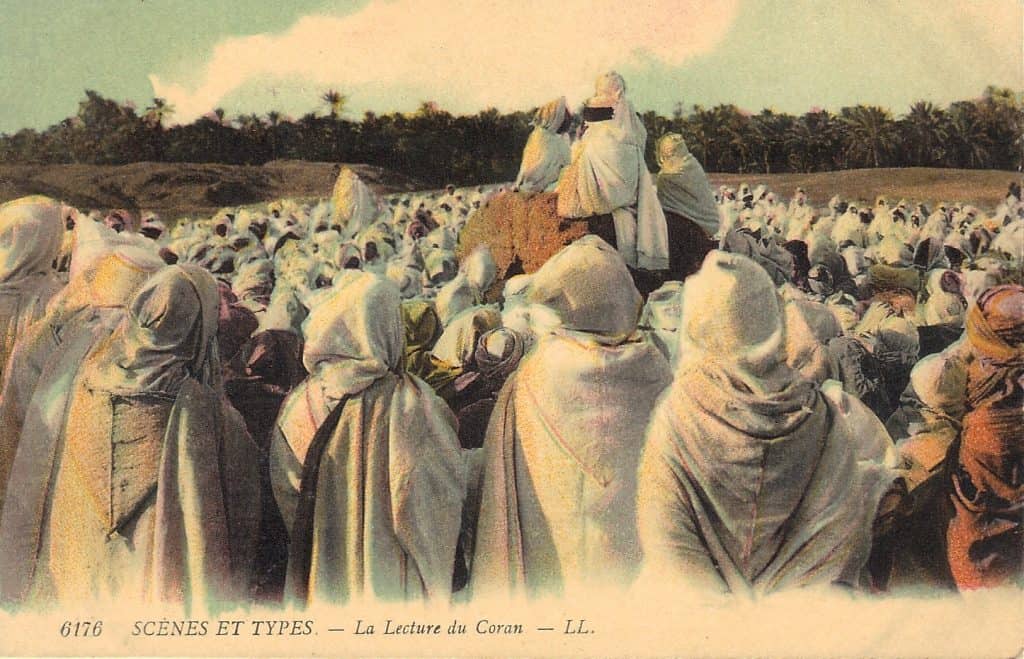

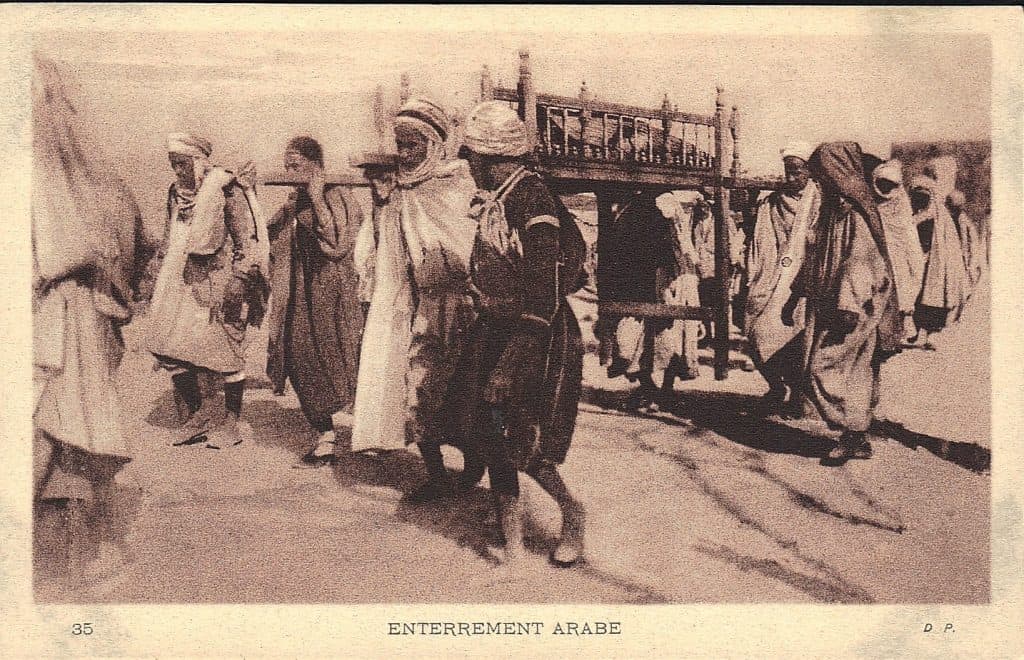

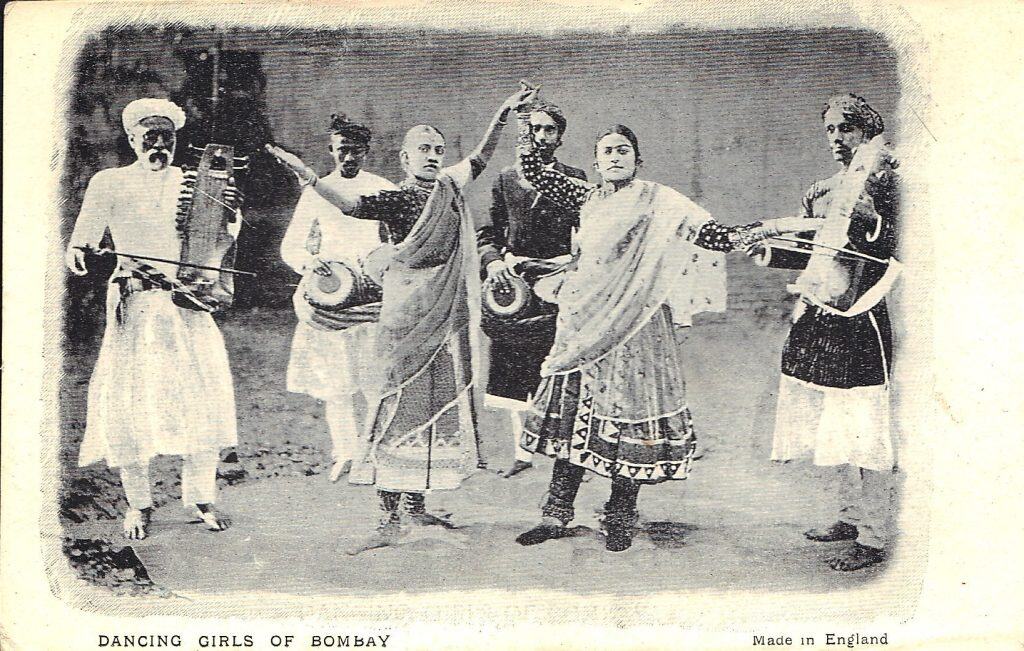

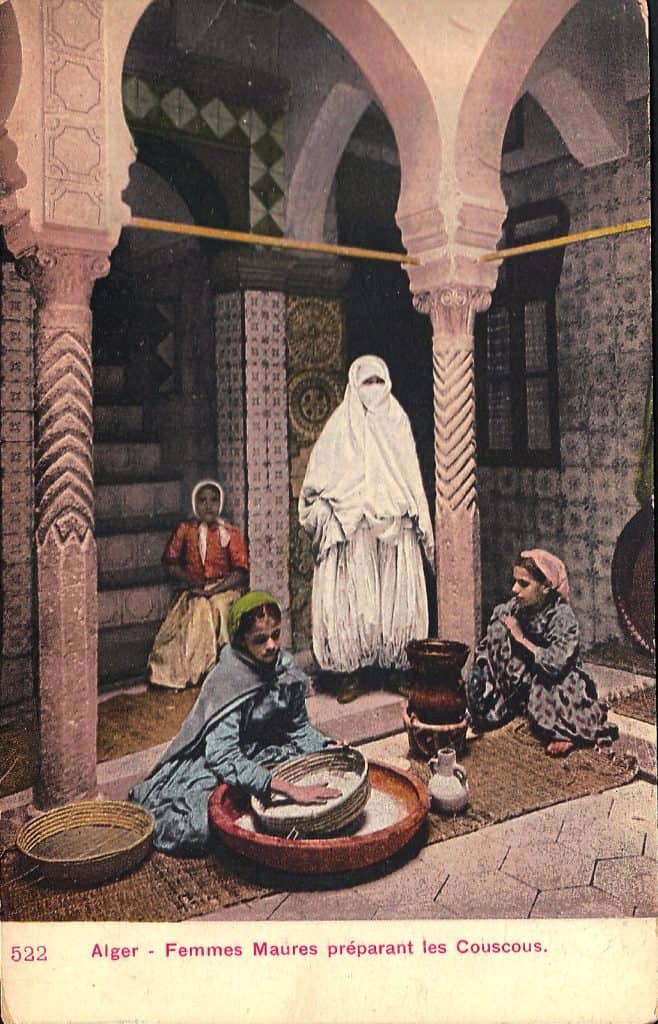

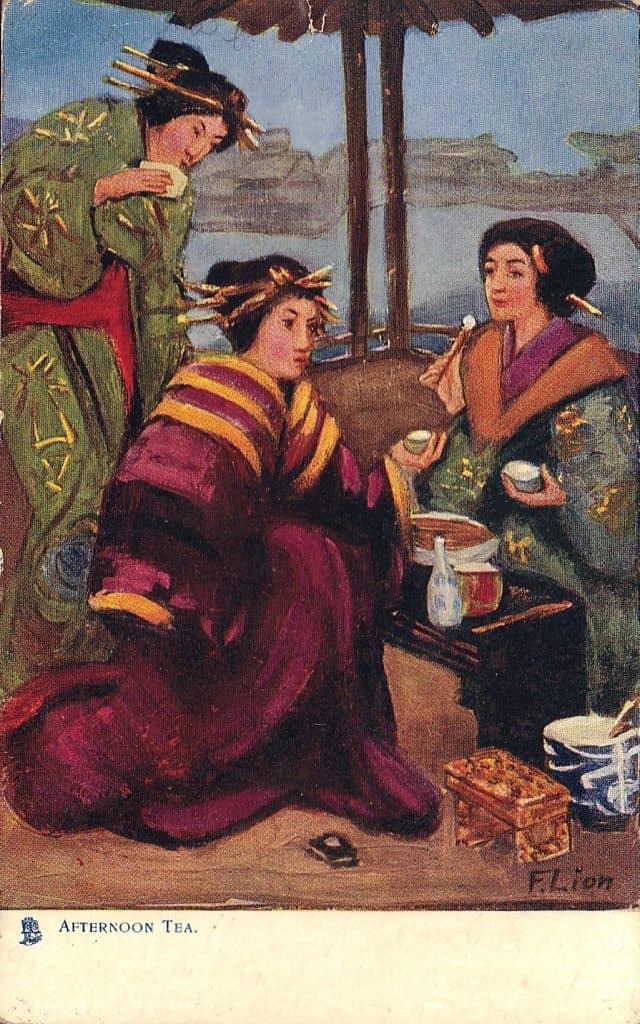

What cultural postcards communicate can vary from native costumes and dance to local occupations and markets, housing and decorative styles. They may also depict local food production, body decoration, forms of religious worship, local festivals, and course of life customs like courtship, marriage, and death.

As historic evidence, however, cultural cards contain many deficiencies, which render them suspect as ethnographically accurate documentation. First, nearly all cultural cards were produced during the Age of Imperialism and its attendant division of the world into empires, protectorates and colonies. The presentation of culture in this context is not value-neutral but is often accompanied by colonial attitudes toward subjected people, ranging from patronizing to contemptuous. In most cases, local people are projected as childlike and colorful curiosities. Often, minorities and indigenous cultures are represented by their majority cultures only through their crafts, art forms, and styles of worship.

A colonial attitude is also often responsible for a fixation on a culture’s sexuality and unusual forms of ritual expression – for example, by displaying bare breasted women in provocative poses and by picturing sensationalistic things being done with bones. These cards tend to represent the views of unsympathetic outsiders.

Colonialism has not been the only enemy of local cultures – the greater antagonist has been “mass society” intruding via mass communications, the internet and the force of national economies. The temptations of the larger society are irresistible to young tribal members and village dwellers. It has always been hard to keep the kids on the farm after they have seen “Gay Paree.” Not surprisingly, some of the traditional cultures depicted on postcards live in preserved domains where contact with the larger society is limited.

Despite these limitations, cultural postcards are an unusually valuable resource for cultural historians and anthropologists because they typically capture ways of life that have been lost or transformed. Scholars may legitimately argue about the accuracy or sensitivity of various depictions; nevertheless, postcard images are representations of cultures at significant points in their development.

Often, a postcard image says more about a dominant culture than about a“native.” For example, at the turn of the 20th century it was popular to include exhibits of families from “exotic” cultures at amusement parks like Coney Island, at roadside exhibits, and at zoos. These native peoples were exhibited as colorful curiosities and were thought of at a level equal to caged animals. The entire institution of human zoos demonstrates the coldness and disdain that once characterized our approach to native cultures.

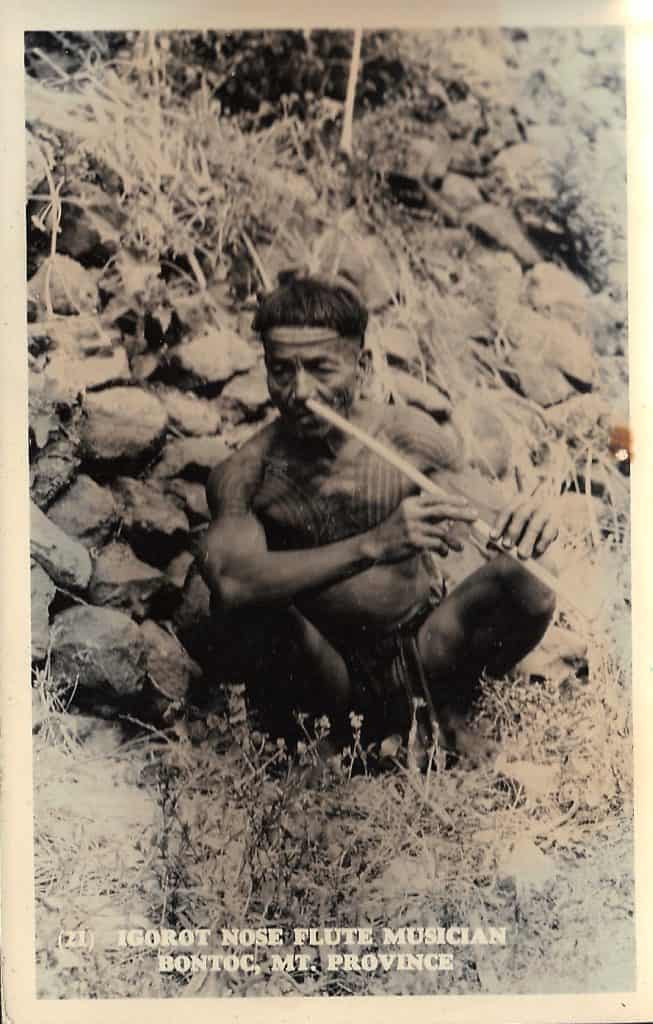

Every period in postcard history has produced its own cultural postcards, however, the most interesting examples are the many real photo postcards created between the 1900s through the 1950s. Real photos have the advantage of being the least “filtered” by social prejudices. They also show the clearest details of costume and other artifacts as presented by the local peoples themselves.

Collectors all over the world and especially from the Middle East, Central and Southern Europe, and Latin America are embracing cultural postcards as artifacts of their own heritage. These collectors are eager to document and preserve their ancestors’ customs and habits. For everyone else, collecting cultural postcards is a way of appreciating and preserving the vast diversity of the human experience.

How interesting!

I wonder if my grandfather (a politically liberal minister) and his wife realized they were patronizing a “human zoo” when they sent me a postcard from a Seminole village during the 1960’s.

Interesting article with GREAT postcards! Thank you.

Human actors? – these people were actors,entertainers – you consider Disney actors working in a human zoo? – that language is a bit ‘rich’

The postcard showing tea pickers in Sri Lanka makes me think that I have the beginnings of a thematic collection with my cards showing hops pickers in upstate New York and violet pickers in France.