In early May 1819, Henry Shaw stepped off the steamboat Maid of Orleans onto a St. Louis dock along the Mississippi River at about where the Gateway Arch stands today.

Henry was a nineteen-year-old Englishman with a shipment of Sheffield cutlery and the equivalent of $3,000. He bought a one-room shop and started a business supplying those who needed hardware. At the time ironware was one of the few commodities that the average farmer couldn’t make on his own. They had to purchase hardware and Henry was the only source.

By the time he was forty, he had made enough to retire. He thought he may like to travel. He left for Europe.

Shaw traveled to Europe three times and spent most of the next decade there. After his first trip, he decided to return to St. Louis and make it his home. He became a U.S. citizen in 1843.

the Shaw Garden Gift Shop

In 1849, he commissioned George Barnett, an English-born architect and friend, to design and build a townhouse in St. Louis and a country estate on the edge of the prairie. When construction was finished, he named his estate Tower Grove.

While in England, Henry rediscovered his boyhood interest in botanical gardens, and immediately decided to pursue his dream of giving St. Louis the same kind of gardens the Europeans had enjoyed for generations. Knowing that he had acquired enough property in Missouri to accommodate that dream, he immediately set upon fulfilling it when he returned to America.

Part of Shaw’s real estate holdings encompassed nearly a thousand acres on the edge of the prairie that Shaw himself once wrote about, “… it is uncultivated without trees or fences, but covered with tall, luxuriant grass, undulated by the gentle breeze of spring.” Hence, it became the land on which he chose to build his legacy home that he named Tower Grove. Here too, would be the garden he wanted to give St. Louis.

The name Tower Grove was inspired by the house’s significant tower, which overlooks a grove of oak and sassafras trees.

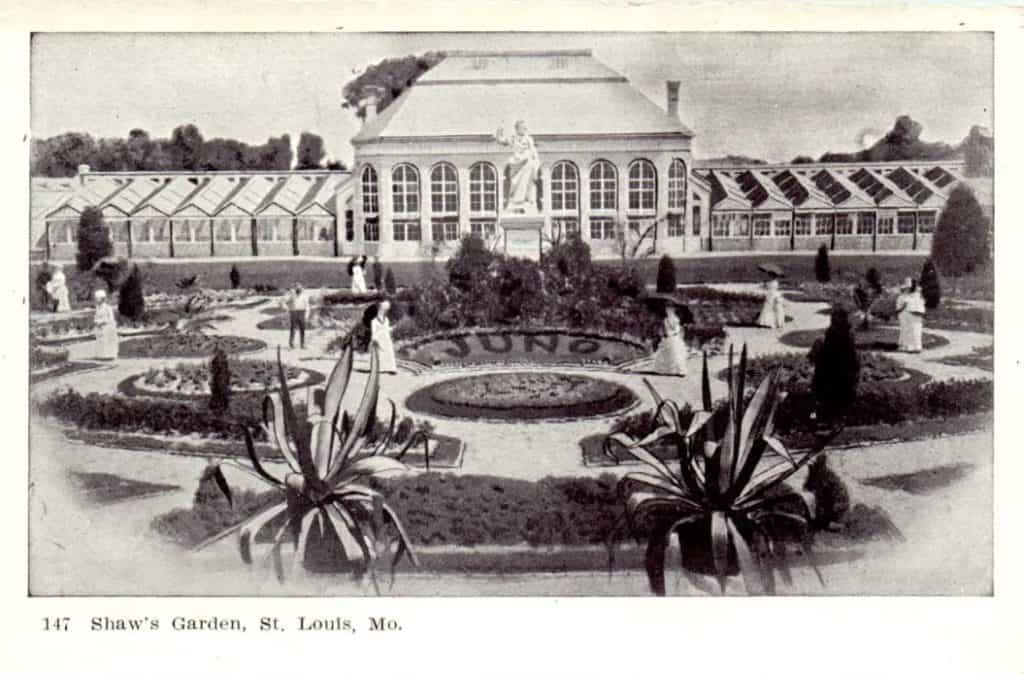

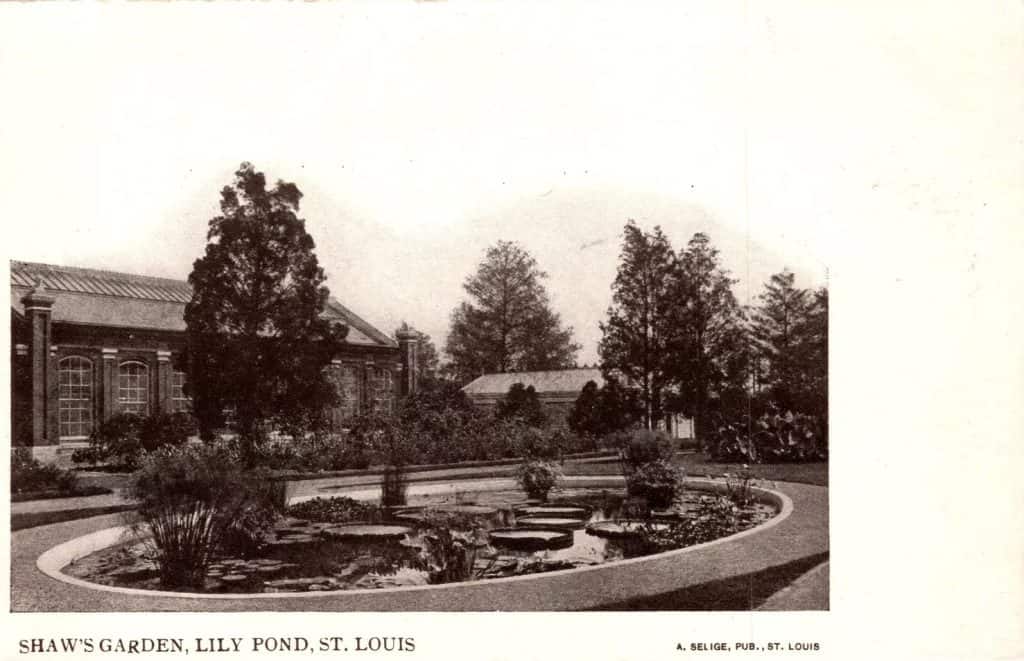

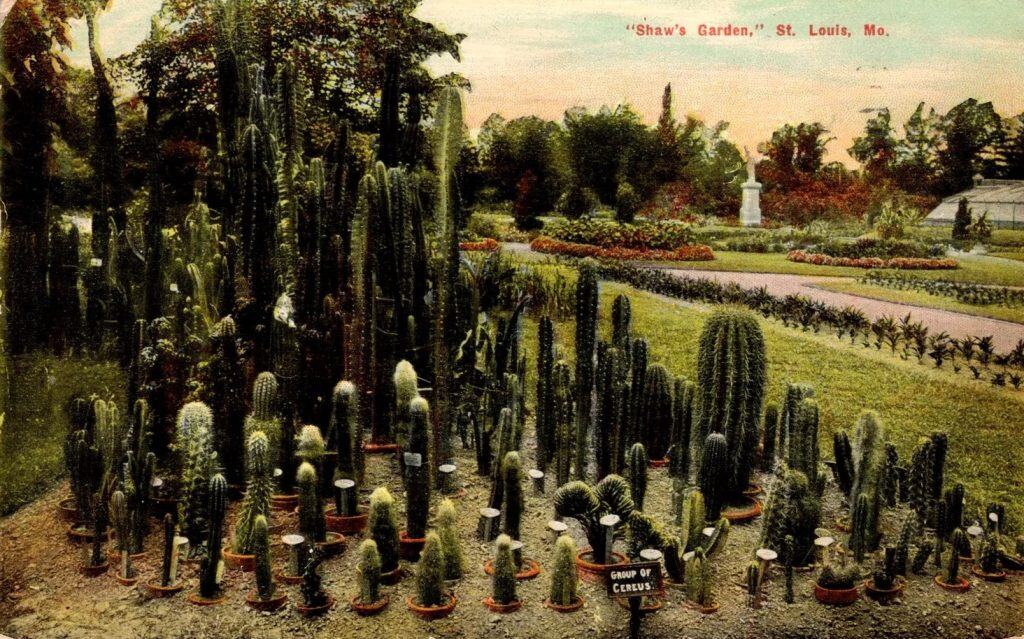

The Garden opened to the public in 1859. Henry Shaw spent the next 30 years watching the community of St. Louis enjoy his garden. In the meanwhile, he established a botanical research legacy that is still vital today. For him, it was the science as much as it was beauty.

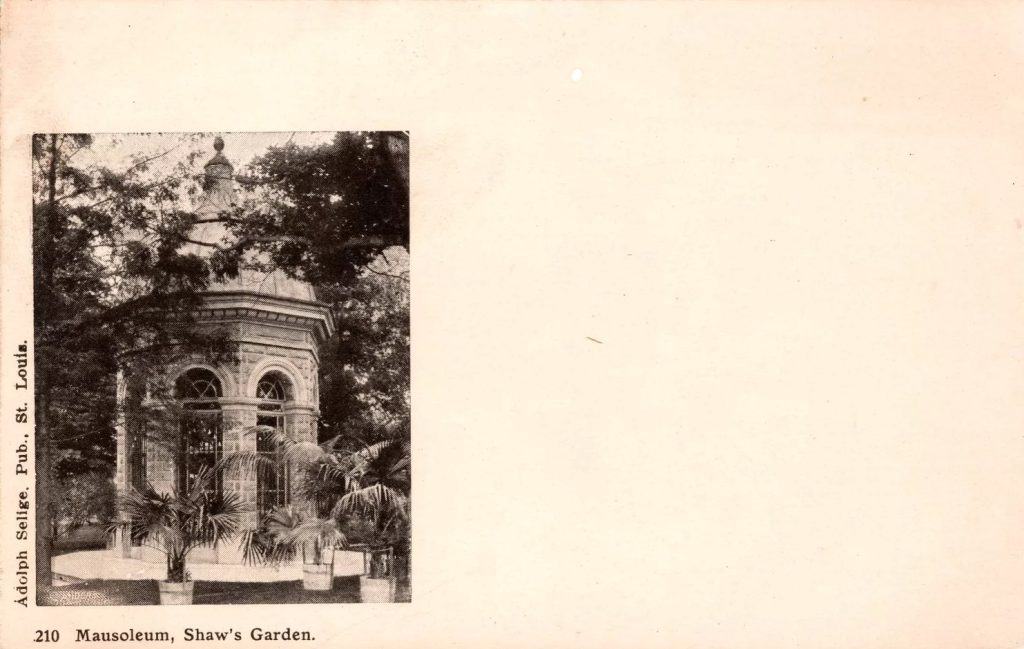

Upon Shaw’s death in 1889, he had pre-arranged for the construction of his mausoleum within the garden. He bequeathed the gardens, the buildings, and the property to the head of the Washington University School of Botany, Dr. William Trelease.

There is no way to know the thoughts of a dead man, but there must have been an element of humility in Henry Shaw. The only additional stipulation in his will was, a guaranteed $200 each year to the Episcopal diocese, provided that the bishop agree to preach one sermon each year on his favorite subject, “… the goodness of God as shown in the growth of flowers, fruits, and other products in the vegetable kingdom.”

Nice to know that “Shaw’s Garden” is still delighting visitors!