Summer’s warming temperatures invite explorations into Long Island’s waters for boating, swimming, whale-watching, fishing, and clamming. Every year, East End residents anticipate feasting on shellfish. A dish of freshly shucked clams and oysters are a special treat to be plucked from our bays and inlets, if you’ve obtained your shellfish permit. The New York region has had a long and deep history with its bivalves. Mark Kuriansky, an authority on the subject, writes glowingly that before the 20th century, the Big Apple would have been better known as the Big Oyster.

Reports from early explorers delight in noting the huge proportions of the contemporary product – up to “shoe sized” of 10 inches along Brooklyn’s Gowanus River. Unfortunately, the Gowanus was transformed into a toxic dump site after the area became the terminus of the Erie Canal during the first half of the 19th century.

Opening the tight-fisted mollusk was a challenge before metal tools were designed for shucking, requiring the application of a little heat. The preferred mode of slurping down oysters came to be known as “on the half shell” – a perfect euphemism for what everyone else calls “raw.”

A staple among local settlers and the native tribes like the Lenape who preceded the settlers, oysters were available everywhere, as evidenced by “middens” – enormous piles of shucked shells that once lined our coasts until they were shoveled up and used for road and rail beds.

When Henry Hudson sailed into New York Harbor in 1609, the area contained about half of the world’s oysters and residents of all social classes could indulge. Until the 19th century, needy New Yorkers could stride into our tidal shorelines to gather a bucketful for dinner. Before environmental neglect and overharvesting made them scarce, workers could simply run outside for some freshly shucked oysters offered at seafood stands located everywhere around town.

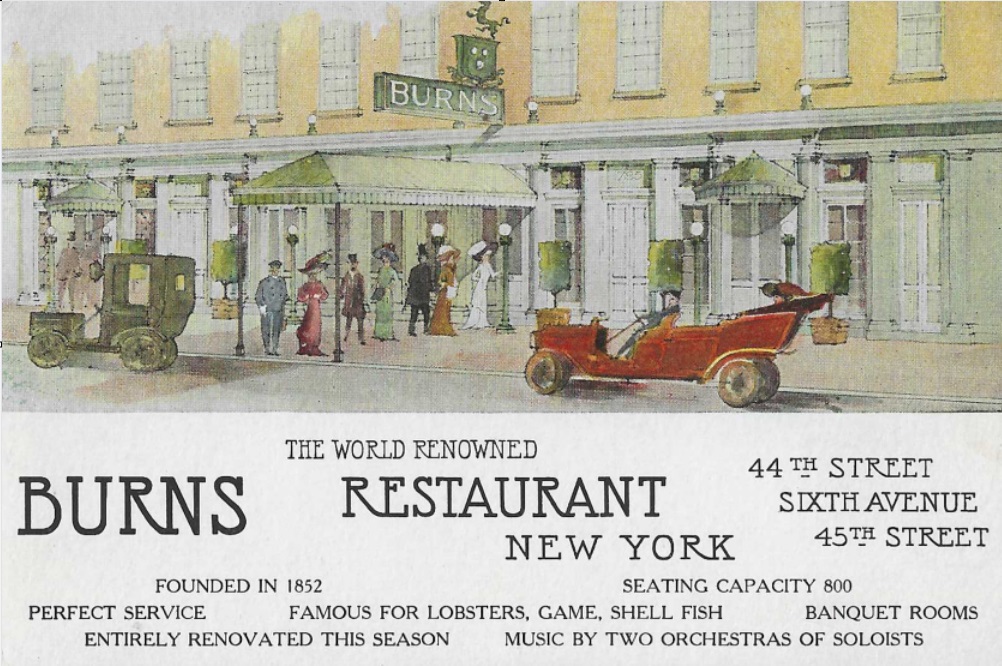

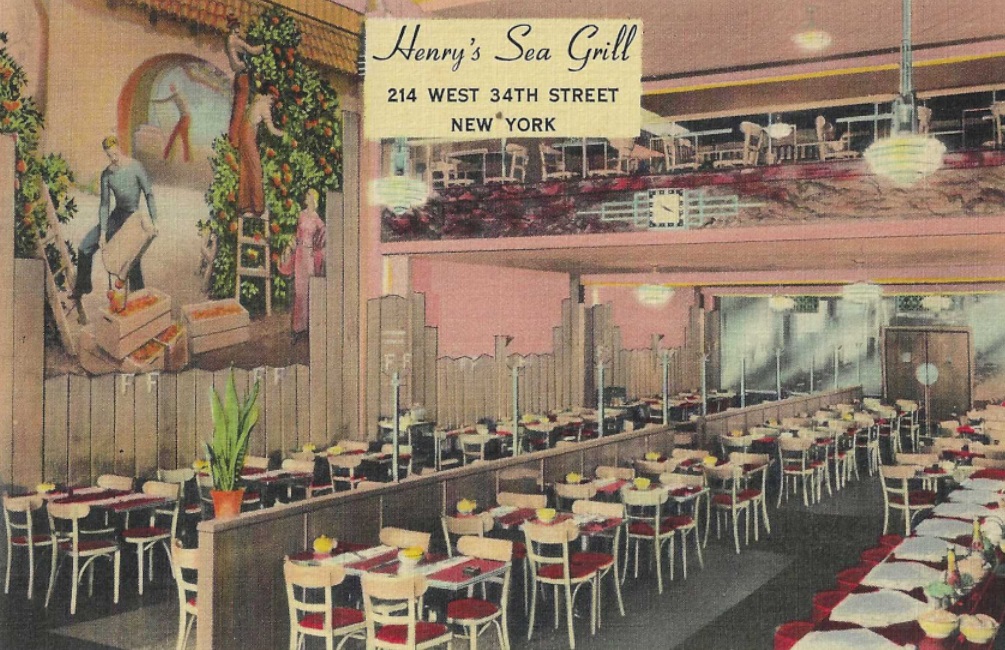

Enough regional oysters and clams survived when commerce, transportation and industry killed New York City’s shellfish industry. Nevertheless, many popularly priced seafood restaurants continued to offer oysters as a local specialty. Restaurant owners depended on products brought in from Long Island, the New England coast and south to Chesapeake Bay.

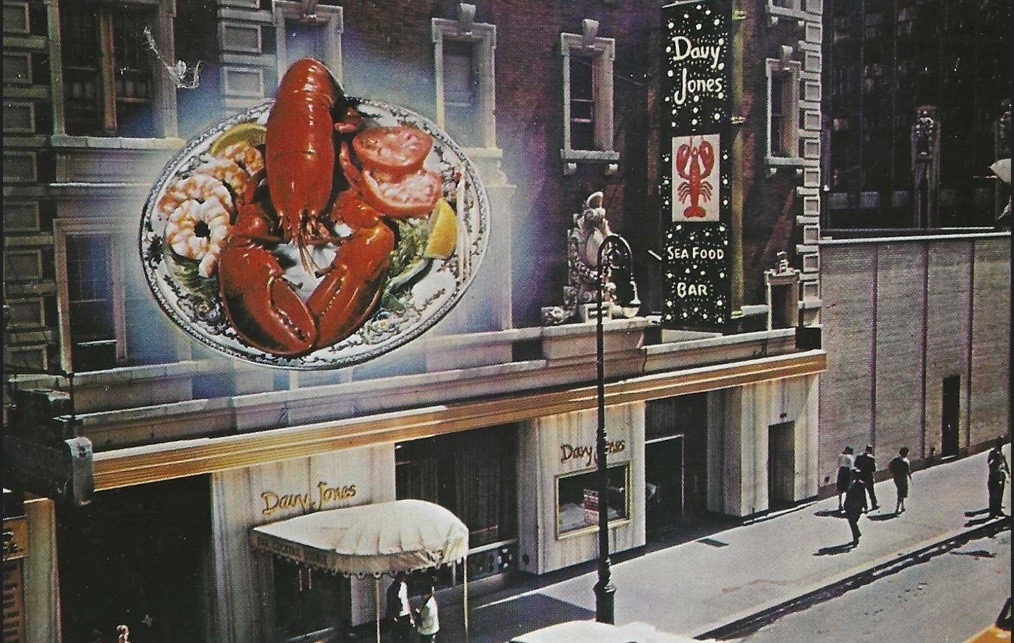

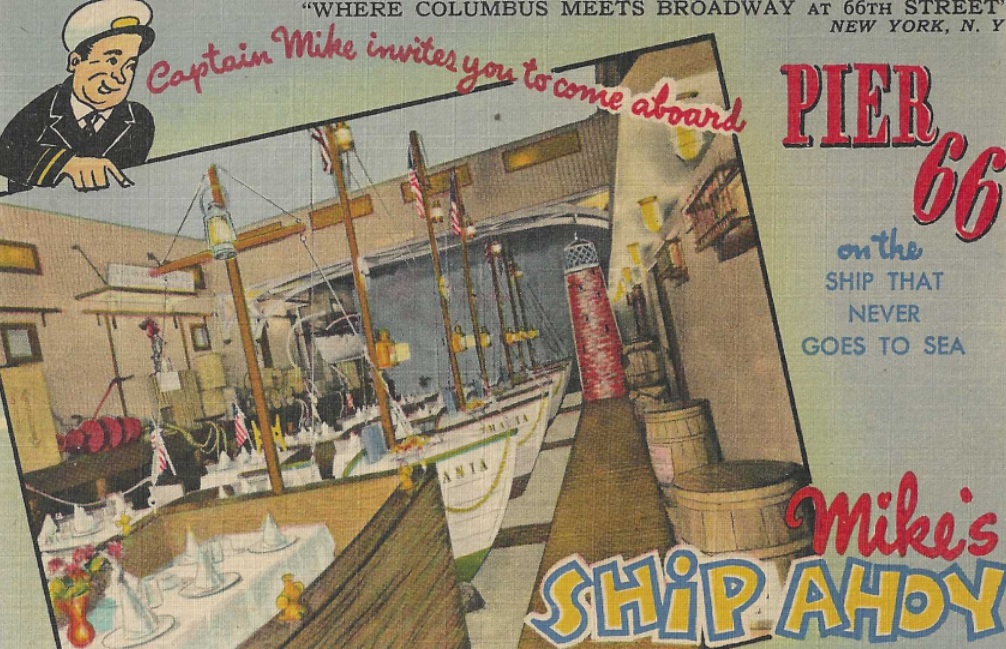

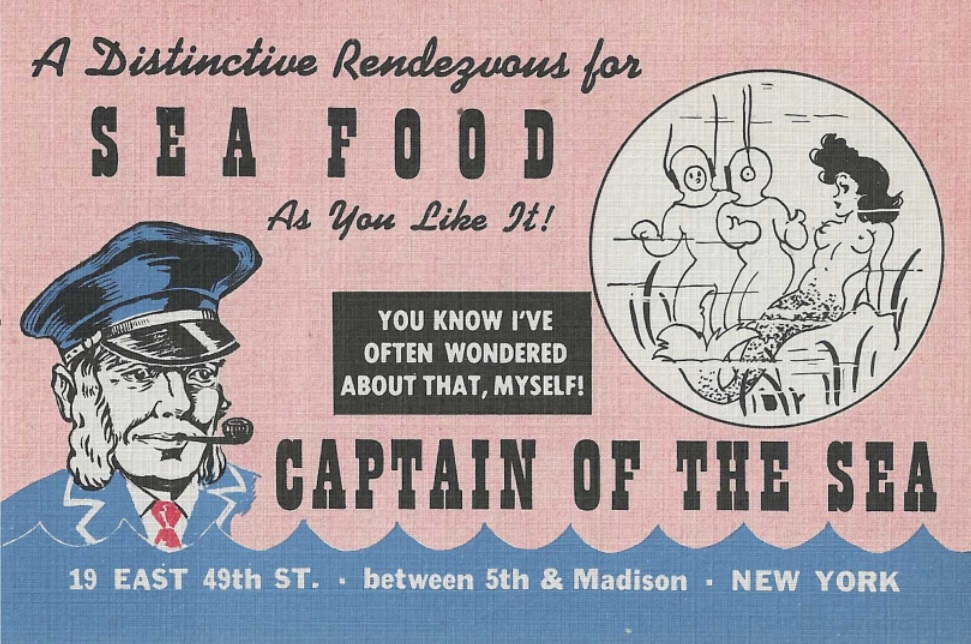

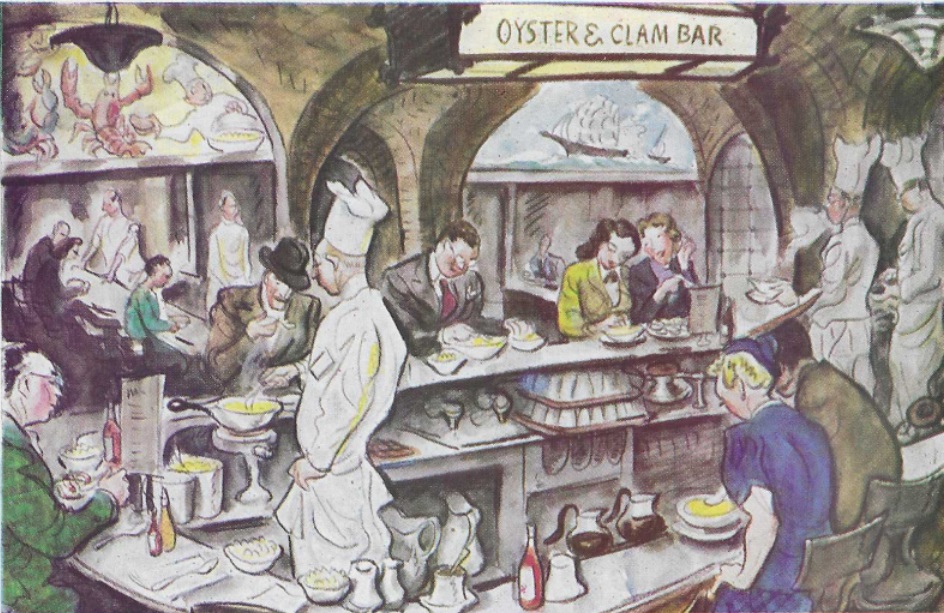

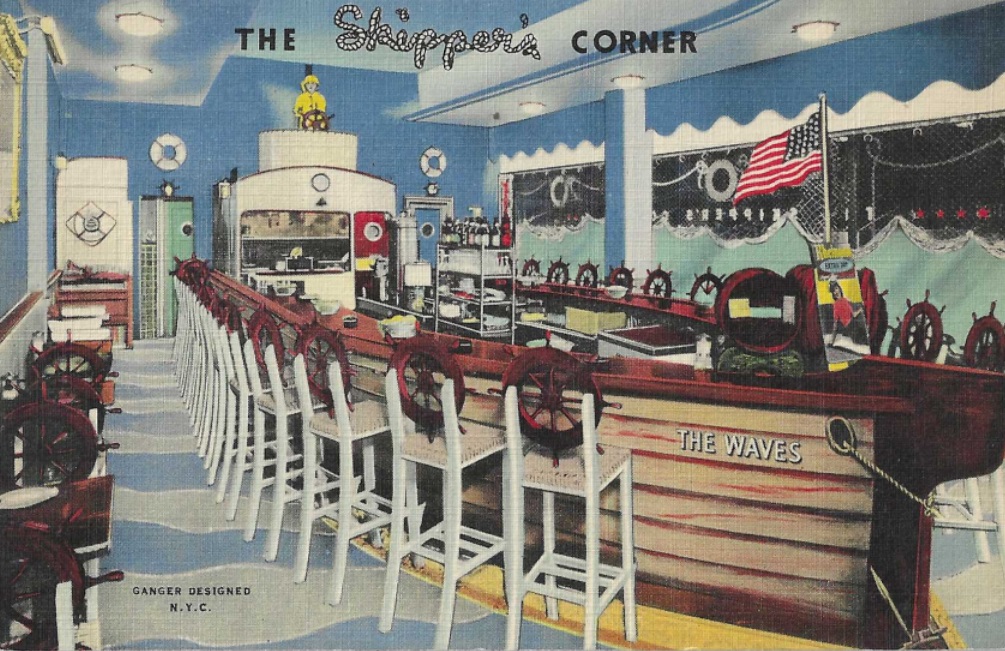

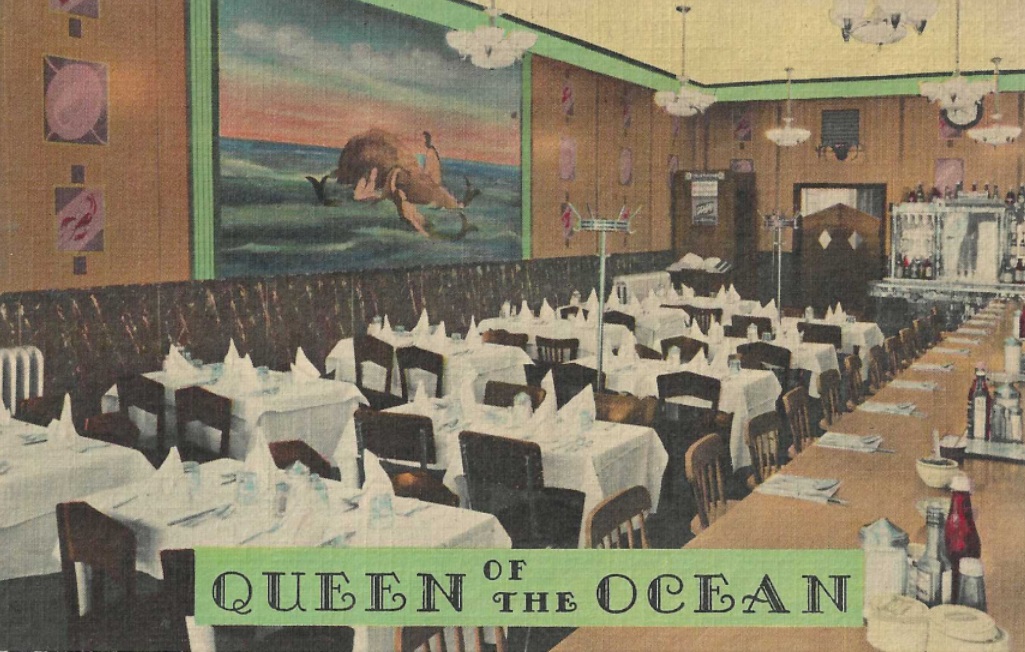

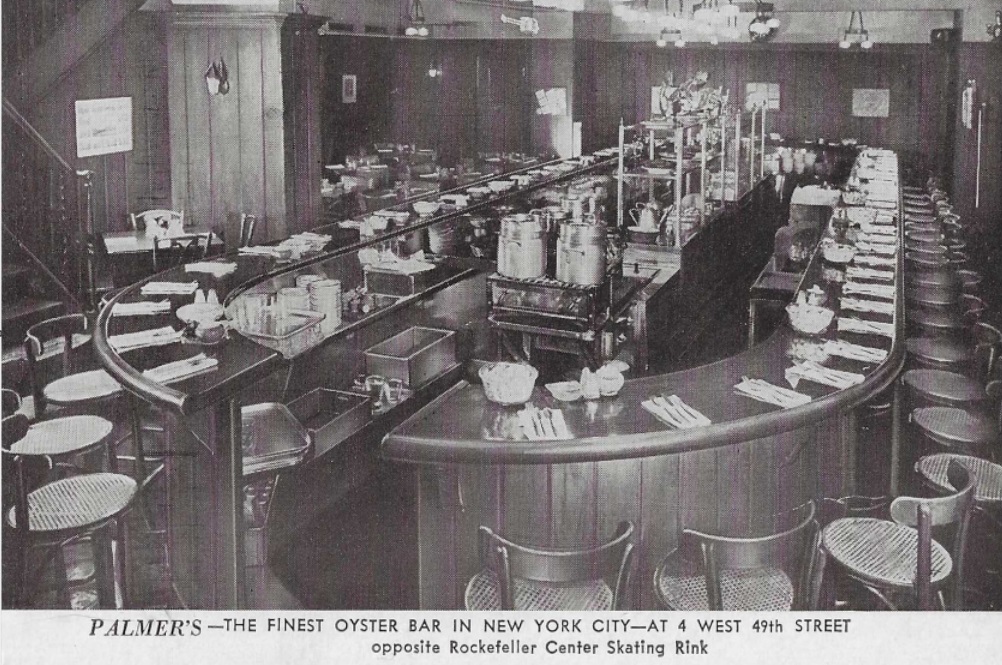

During the postcard era, seafood restaurants offering clams and oysters competed heavily while enjoying strong market demand. The card designs featured as much seafaring kitsch as any single postcard could take. Restaurants did everything to promote their offerings – from Godzilla-sized lobster creations to fleets of dinghies attempting to recreate a New England fishing village inside of a restaurant’s interior. We’re lucky that many great restaurants, each with their own bars for oysters and clams were able to hang on as outlets for simple fare during the “linen” era, the 1930s to the 1950s. As we’ll see, collectors have an amazing array of cards to select, each with their own garish palette of blues and greens set off by hot pinks and reds.

The oldest post cards devoted to this genre of eateries start to show several conventions that became common. First, the utter simplicity of seafood emporia became a prime feature. Seating was on benches or simple pine chairs. Tablecloths were rare, usually replaced by paper or cloth mats. Most of all, the seafood house was built for density. The close quarters encouraged a kind of cheerfulness and conviviality among customers. These restaurants and oyster bars are still great places to meet up and chat with fellow oyster lovers.

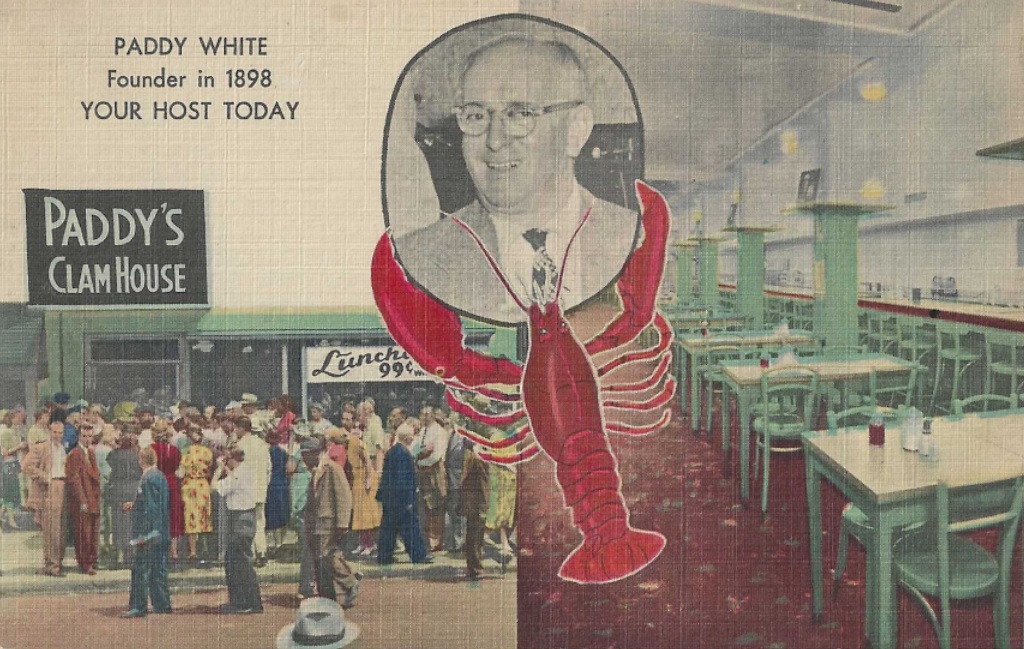

Paddy White’s 1930s linen postcard promises that the crowds at his clam house will be thick. As a lobster is devouring his portrait, the folks are lining up on 34th Street ready to chomp down on some cherrystones, as the mid-sized clams are called. About 112 million clams were harvested each year in New York so there was always ample supply.

Oysters and clams are cultivated in a similar manner and kindred, though not identical knives are used for “shucking,” that is, opening the mollusk and extracting its meat. Some Hamptonites exhibit bumper-stickers express sentiments like “Go shuck yourself,” when they want to be subversive toward visitors coming from west of Queens.

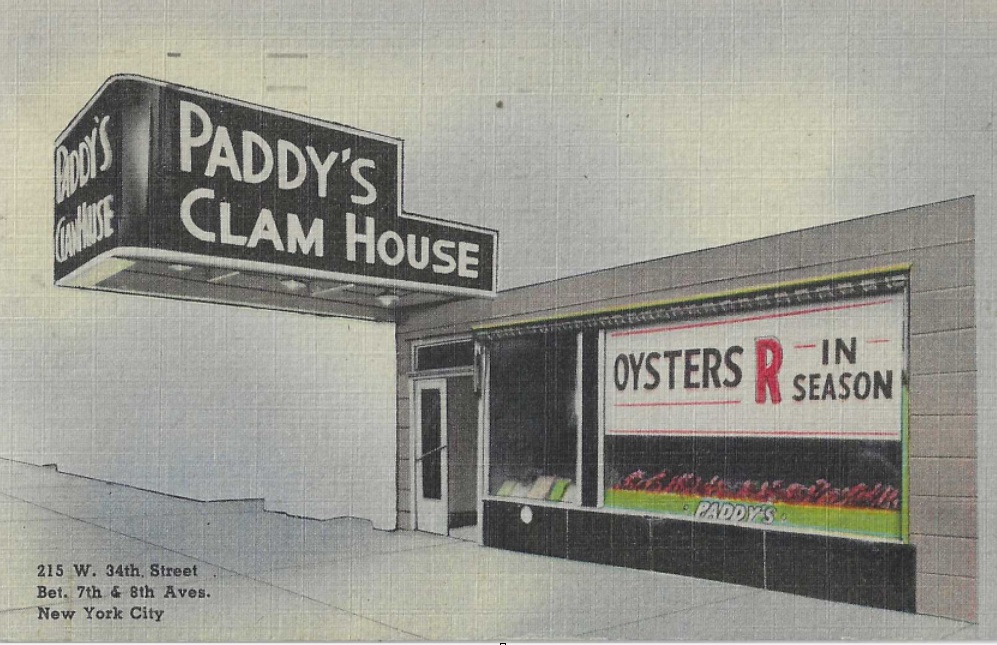

The front window of Paddy’s Clam House’s second postcard shows one of the most controversial beliefs about oysters – that the treat is edible only during months whose spelling contains an “R.” Although avoidance of oysters during the summer months is relatively rare today, evidence of the practice goes back 4,000 years. The reason for seasonal avoidance of the bivalve at this time of year is because oysters in the wild experience an increase in vulnerability to bacterial infections. Experts also point to a loss of flavor during warm weather, suggesting that the optimal months for flavor are from September to December.

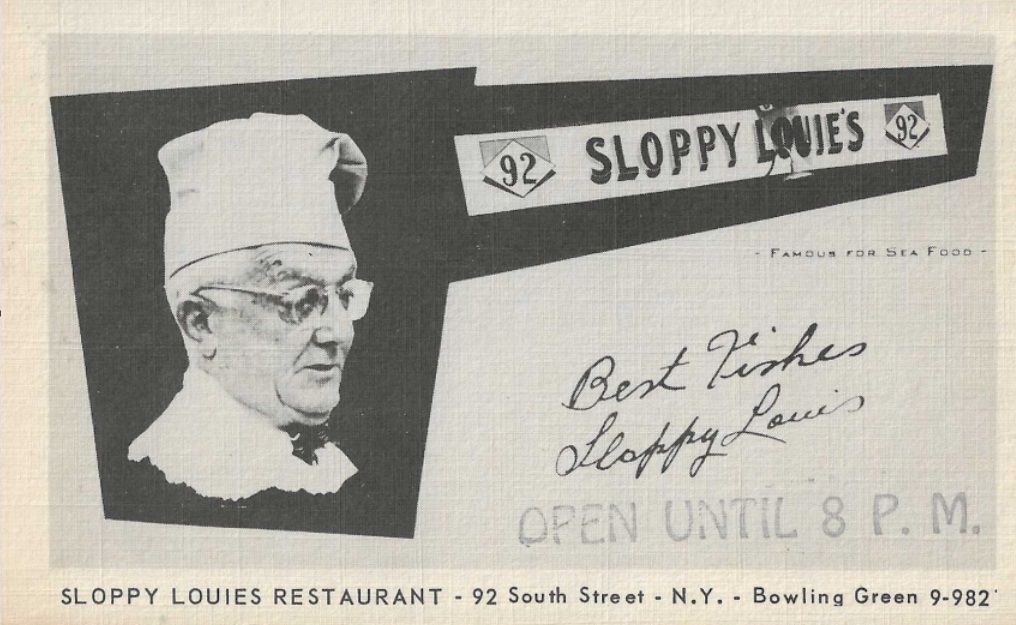

The experts also note that the increasing tendency to cultivate oysters within scientifically controlled environments has largely eliminated fears of contamination and has evened out the natural flavor cycle. Oyster bars of today would certainly be unlikely to name themselves after “Sloppy Louie” – a classic mainstay of the old South Street Seaport. Critics who would champion skipping an oyster treat during summer months should simply “shuck off.”

Interestingly, when oysters grew scarce during the 1950s, we began to see them promoted as a luxury food rather than as a simple treat – to be enjoyed with a flute of champagne instead of alongside a beer. This card from Sea-Fare located at 1033 1st Avenue in Manhattan’s upscale Sutton Place neighborhood presents itself as fashionable and tony – not working class and lusty.

Judging from the voluptuous designs of period postcards, the World War II years and the epoch immediately following seem to have been a kind of golden age for New York’s oyster and clam bars. The movie theaters were active. The nightclubs and Broadway were booming. The subways and trains were running late into Penn Station and Grand Central. But then, overharvesting and raw sewage being dumped into New York’s harbors began taking their toll. New York’s raw bars were vanishing. Some survived by adding lobsters and chowders to their menus and by moving from Manhattan into the city’s boroughs.

By the 1970s it seemed that New York’s shellfish had no future as Broadway declined and the areas near the subway and train stations turned into slums. It took several years to restage and renovate Midtown Manhattan – some of it at the initiative of an ambitious and visionary real estate developer named Donald J. Trump.

Shellfish also had a natural ally – the tendency of the species to improve itself and recreate its surroundings. Oysters clean the waters in which they live, capable of filtering up to 50 gallons of water per oyster, per day. They also act as keystone species, attracting other marine life to live around them, from microscopic organisms to crabs and fish. Restoration efforts such as the Billion Oyster Project are linked to the shellfish’s capacity for regeneration.

Does New York have a favorite oyster bar? The answer is usually an enthusiastic “Yes!” and typically the Grand Central Oyster Bar is named. This classic seafood restaurant is in the lowest level of the great train terminus and depicted here in this postcard by George Shellhase (1895-1988). Little has changed since the restaurant and oyster bar were built in 1913. The Oyster Bar still shows off its vaulted Guastavino tile work and its bespoke chowders made at the counter by white-suited chefs.

Great article, thank you. I have a very nice “Linen” collection, in which restaurants are represented, Also earlier Coney Island cards.

steamed, please! – thanks for the post

Hey Hy! As I mentioned when we met at the postcard show in Manhattan last June, every time I read one of your articles, I go on a buying spree. Among the many postcards I just purchased, I got a kick out of seeing Paddy’s Clam House 99 cent luncheon, then one with $1.12 covering the 99. Another one with $1.21 lunch special and then $1.29. Bought them all.

Looking forward to your next article.

Actually, I enjoy ALL the articles presented each week on Postcard History but my particular interest is in New York.

I love most seafood, but I’ve never eaten raw oysters, although I have enjoyed fried examples of that particular variety of shellfish.

Great article, thank you! We live nearly 3,000 miles from your oyster area but also share a love of this bivalve which grows well out here in Washington. The Olympia Oyster [Ostrea Lurida] is our own native species. Climate and water conditions are still good for growing the native plus imported varieties such as Kumamotos, Belons, Pacifics and others. I’ve fond memories of slurping a raw oyster or more while sitting on a local rocky beach.

Thank you again for such a well written article.

A very interesting article but I found it very difficult to past the sentence blaming the Erie Canal for the pollution of Brooklyn’s Gowanus River. The Erie Canal ran between Albany and Buffalo, connecting the Hudson River to the Great Lakes. There are some 165 miles of the Hudson Valley and a great many sources of pollution along the waterways separating the Erie Canal from Brooklyn.