When scholars study the paintings of Winston Churchill they are artfully introduced to an unexpected dimension of a multifaceted personality. Churchill’s art captures more than temperament and disposition. Depending on the demands of leadership, his artwork brings a historic commentary that resonates with the struggles of his time. Any serious study of his work reveals an appreciation that is rooted in patriotism and resilience. Ultimately, Churchill’s paintings invite us to rethink the limits of creativity when the restraints are the responsibilities of leadership. Nearly every assessment, true or imagined, of his contributions to the realms of politics and painting, will come to understand that Churchill was not merely a wartime leader but an artist who sought out the beauty of life.

Throughout his years Churchill painted some five hundred pictures. His paintings are well known for the wide variety of subjects – from the gardens and goldfish pond at his home in the English countryside to the buildings in many European cities and in several African nations. His work is held by more than sixty museums around the world, and his original paintings are now seen occasionally on auction blocks and the bids are generous.

Postcards showing Churchill’s art are few in number. There is no evidence that only one publisher of postcards has made cards of Churchill’s work, but at this time the only known concern is a small London company named Soho Gallery. Four of their issues are featured here with brief histories of the topic.

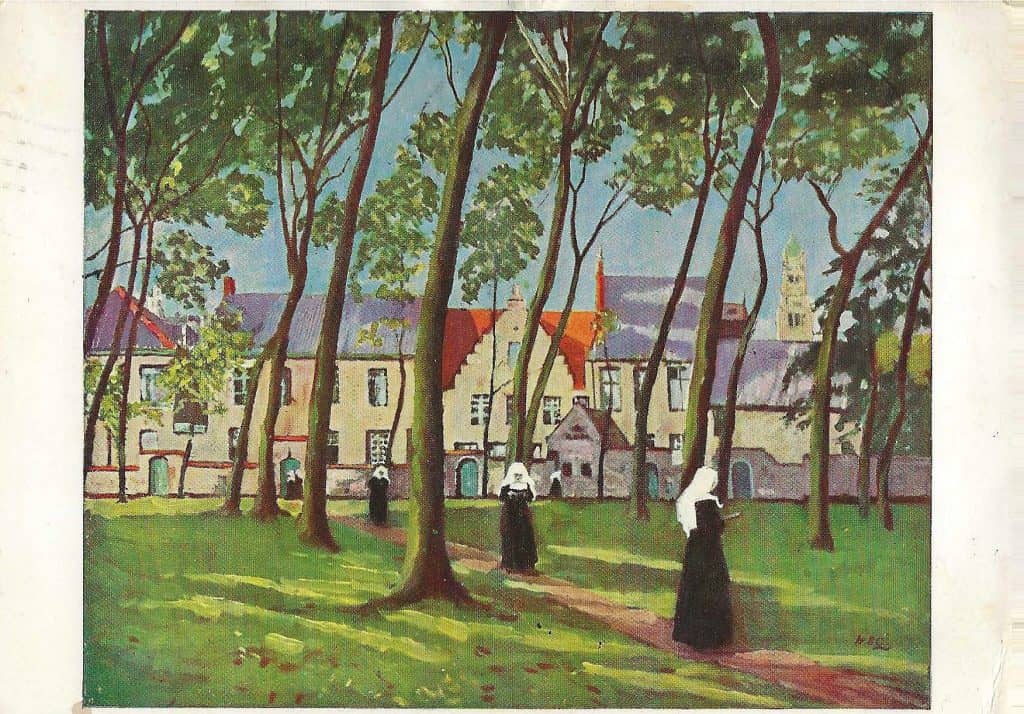

The Beguinage at Bruges is oil on canvas completed in 1946. Beguines were women in the cities of northern Europe, who, beginning in the Middle Ages, led lives of religious devotion without joining an approved religious order. They were so-called “holy women” who first appeared in Liège toward the end of the 12th century. In many cases, the term “Beguine” referred to a woman who wore humble garb and stood apart as living a religious life beyond the practice of ordinary laypeople. Local officials established formal communities for these women that became known as beguinages.

The word dates from the late twelfth century but was seldom used in American English until 1935 when Cole Porter composed his perpetually popular song, Begin the Beguine that referred to a kind of dance rooted in a West Indian culture. Hence, when Chick Henderson, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald sang the lyrics they brought back memories of tropical splendor.

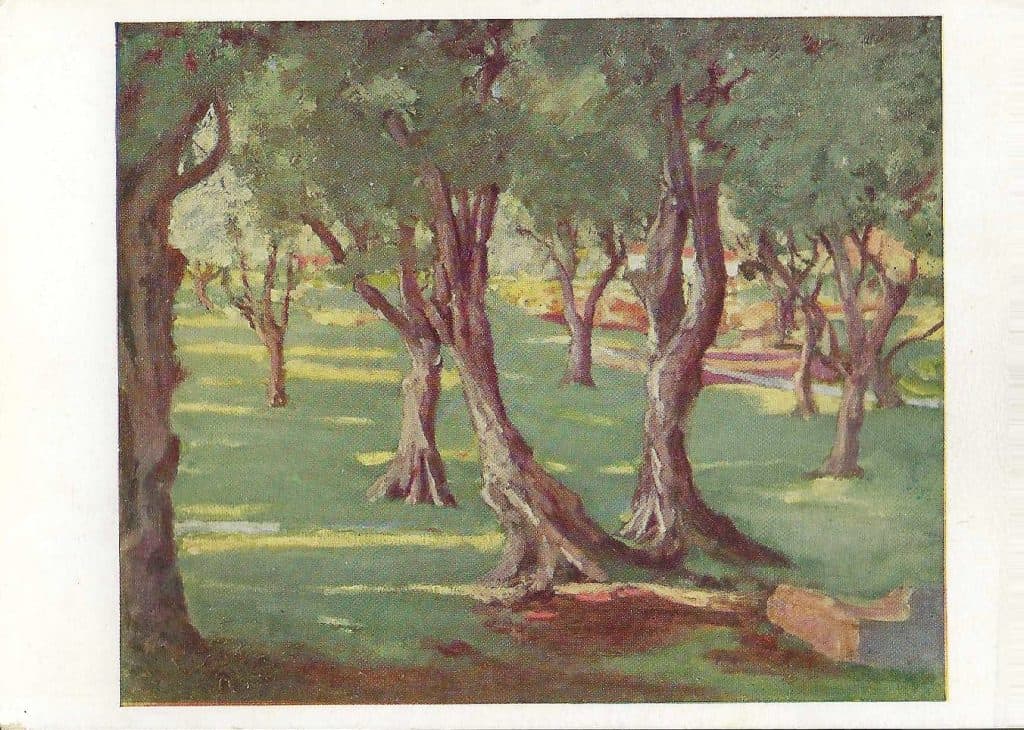

Churchill painted more than a dozen pictures of trees – it was a favored topic, likely because olive trees were not native to the British Isles. An olive tree orchard is the place where nature’s resilience and beauty meet. As you wander through the rows of gnarled trunks and silvery leaves, a sense of timelessness surrounds you. Many of the trees, with their deep roots, have witnessed centuries of human life, but hold their secrets in silence. The essence of an olive tree orchard lies not only in its tranquil appearance but also in its symbolism, wisdom, and fertility.

Each olive tree tells a story. Some display the marks of age, while others stand young and vibrant. An orchard thrives in warm Mediterranean climates, where hot summers and mild winters create an optimal environment. The careful cultivation of olives is an art form. It is a process passed down through generations, merging tradition with nature’s rhythm.

In many countries the olive tree’s fruit is a sacred icon. When the olives appear the green and deep purple fruit creates a picturesque landscape that captures the attention of natives and visitors alike.

Beyond their aesthetic charm, when olives are pressed for oil, it is revered for its flavor and health benefits and becomes a staple in healthy diets. The annual harvest is often a community event filled with fun and song. And life continues, as olive orchards remain a reminder of stillness and simplicity, where one can find profound wisdom.

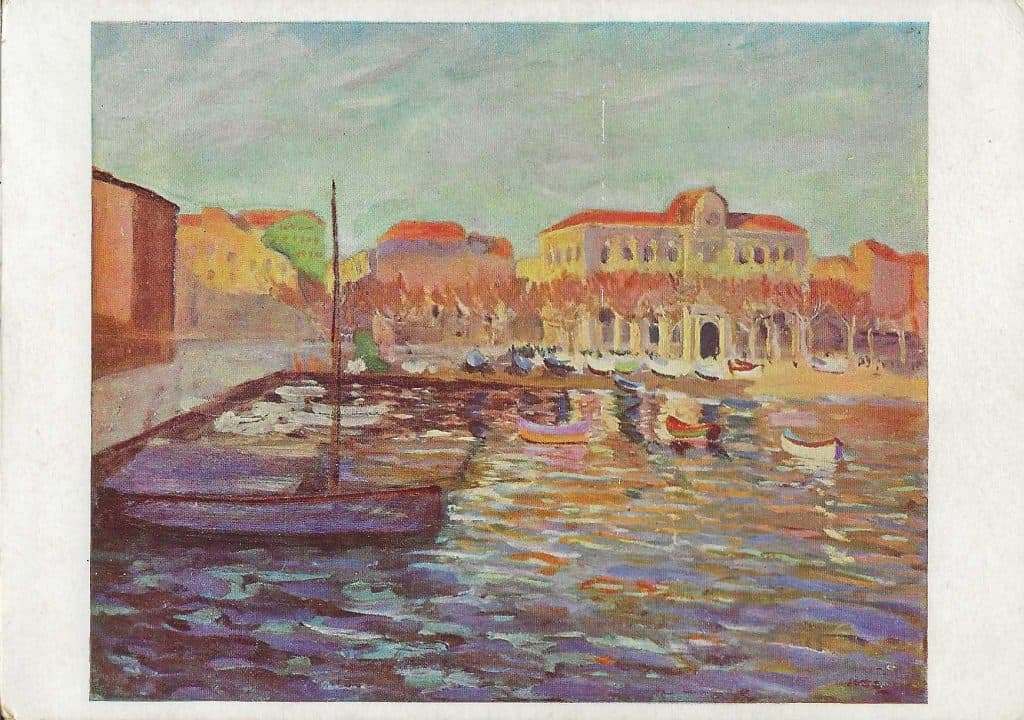

The Harbor at Cannes is one of many oils on canvas paintings Churchill did in southeastern France. Cannes is recognized today as the site of the world’s most notorious film festival, but it has been a much-admired city for centuries. It sits close to the Mediterranean Sea just a few miles west of the French-Italian border.

Churchill’s first visit to the area was in 1921. “St-Jean-Cap-Ferrat,” he wrote in a letter to a friend, “what a perfectly wonderful place to paint on the Côte d’Azuz. My favorite hidden beach is here, whereas you look to the right the Cap is dotted with some of the most magnificent villas in all of the Côte d’Azur—treasures of France. La Villa Santo Sospel is right up the hill where you’ll find a Cocteau Surprise on the walls. Just to sit by the small port on a sunny day is time well spent.”

That year, 1921, had been sad and difficult for Churchill as his mother and two months later his daughter, Marigold, passed away. Clementine and Winston went to Dunbarton Castle in Scotland as guests of the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland where they recovered from their loss, and he painted.

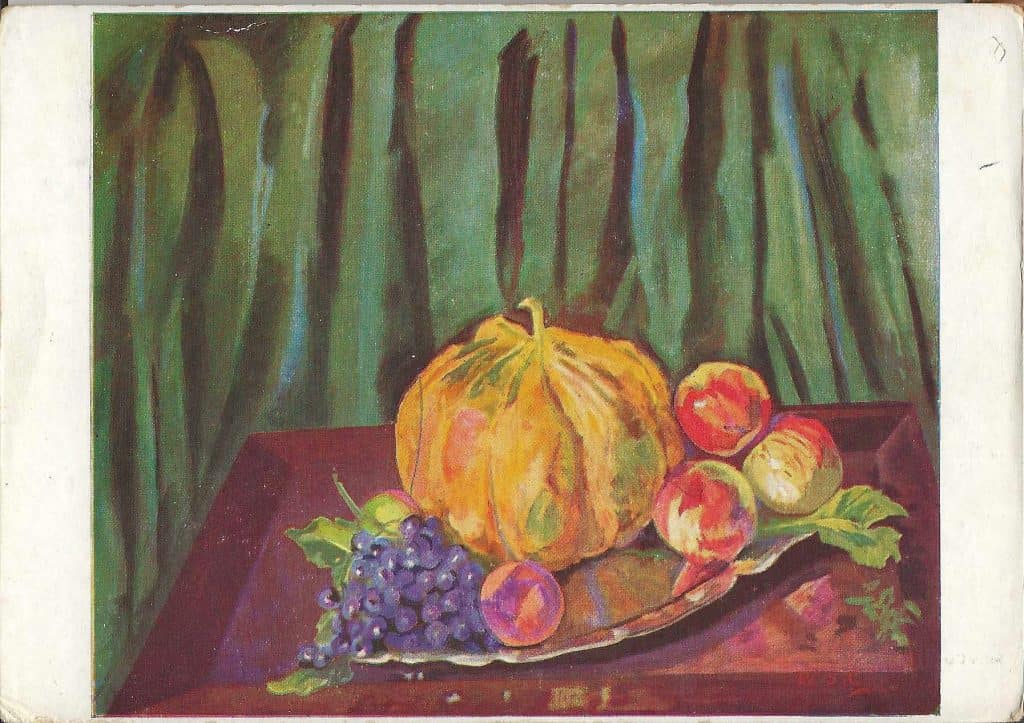

If an artist tells you he has never done a “still life,” he is exaggerating the truth. Still life is an invaluable learning tool for artists, offering a unique opportunity to hone essential skills in composition and lighting. By arranging inanimate objects, like flowers, fruits, or everyday items, artists develop a keen eye for texture and form. Still life, as a genre, sets its own pace – slow! It encourages experimentation. A circumstance seldom tolerated by life-models.

Working with still subjects fosters a deep understanding of perspective and can serve as a practice ground for artists to tackle more complex themes outside of a controlled environment.

Churchill had an appreciation for still life paintings. Like many other artists, he viewed still life as a means of finding beauty in everyday objects. He believed that if an artist successfully urged his viewers to find joy in simplicity and the mundane, he would later find joy in the complex and exotic – nature, architecture, and portraiture.

Ultimately, Churchill’s admiration for still life revealed his understanding of art’s power to evoke emotion and inspire thought in his rapidly changing world.

Clearly, you are a good critic.

thanks

Churchill was also a writer of note — his four-volume A History of the English-Speaking Peoples is especially highly-regarded.

Enlightening! Well done! Churchill, the man, is an inspiration and challenge to us all.

A wonderful article. Churchill was a fascinating man. I have read that he was not raised in a particularly loving home and that his parents had little time for him. To me he seems a strong

testament to the human spirit.