Singers

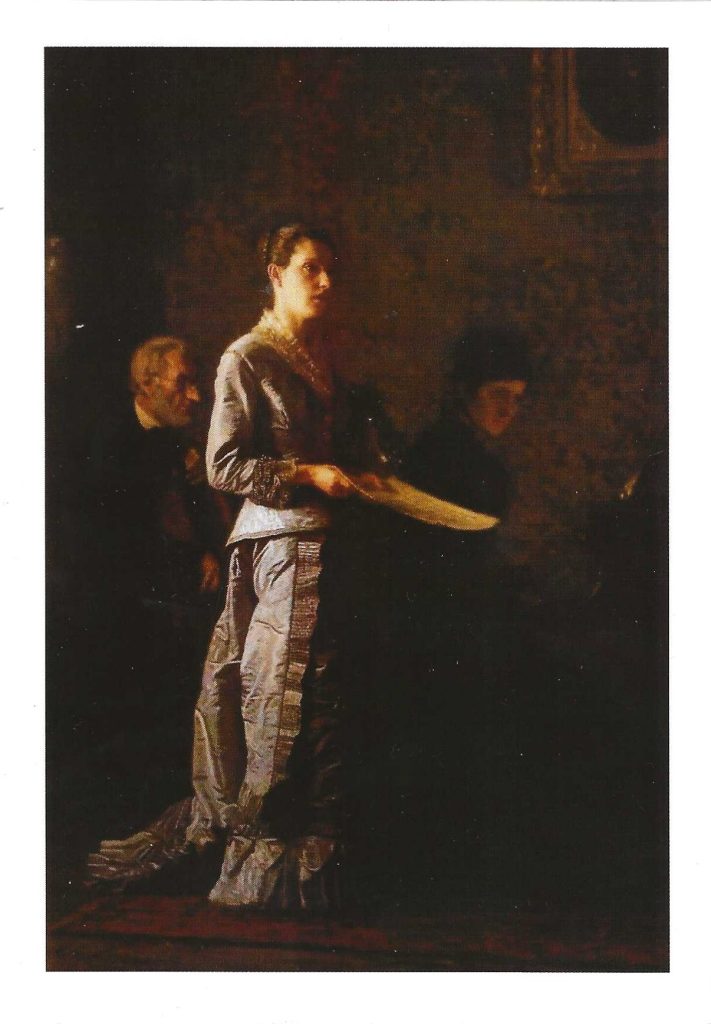

Thomas Eakins’s career centered on portraying upper-middle class residents of his native Philadelphia. His depictions are far from static likenesses; they show individuals engaged in their chosen profession or avocation, whether they are along the banks of the city’s rivers, in the parks, or in public and private performance venues. His 1881, oil on canvas painting Singing a Pathetic Song is an exquisite example.

The home musicale was a frequent event and universally popular in the late nineteenth century and Eakins took advantage of every opportunity to have friends and neighbors perform for him as an audience of one. In Pathetic Song, an earnest young singer accompanied by a pianist and cellist seems to concentrate on holding a note as an example of her skills.

The “pathetic song,” was a popular genre of music in the 1860s and ‘70s. It told of woes, such as death or tragic circumstances befalling innocent women or children and when sung by a singer as autobiographical, it often moved audiences to tears.

The painting remained in Eakins’s collection until late 1885, when it was traded for a painting owned by Edward Hornor Coates, a trustee of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

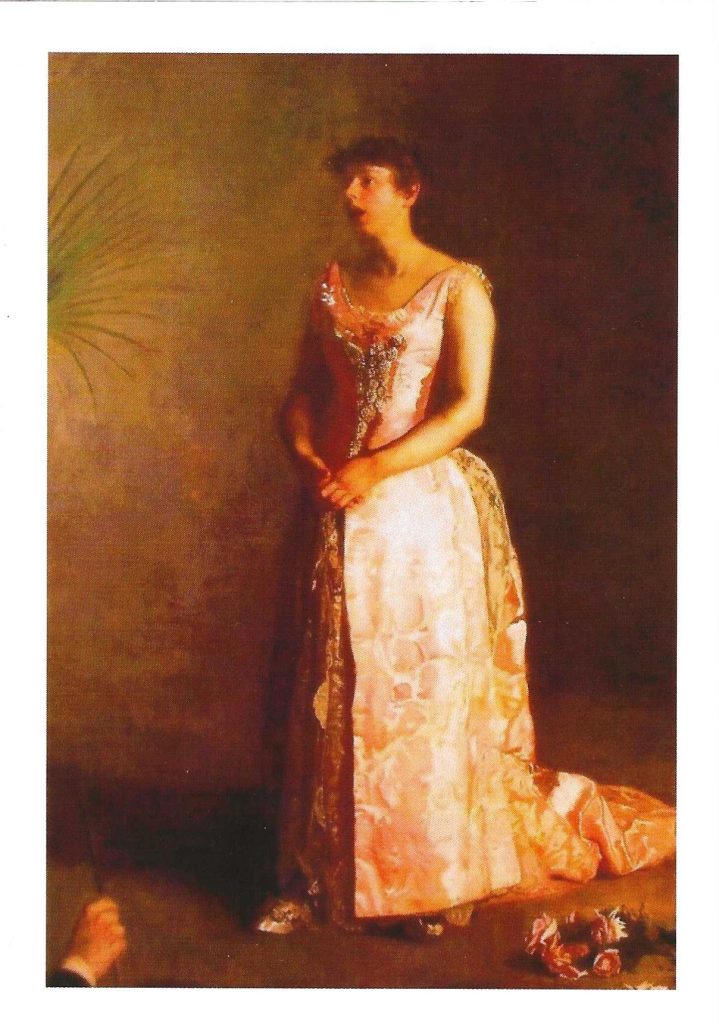

Eakins painted at least a dozen pictures dealing with the visual aspects of music. The Concert Singer, a painting he started in 1890, has been called “the finest.” It has a long and bazaar history. The subject is the accomplished opera contralto, Weda Cook with whom Eakins had a serious disagreement over his insistence that she sing while posing.

Weda Cook was a New Jersey socialite who was respected as a vocalist and recognized for her unassuming manner. She attempted to buy the painting from Eakins, but he refused her offers claiming that he was unable to sell it because it had not yet met its exhibition potential.

After his death the painting was appraised for only $150 (Cook had offered much more!). The painting was given to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1929. It was his first full-length portrait of a woman.

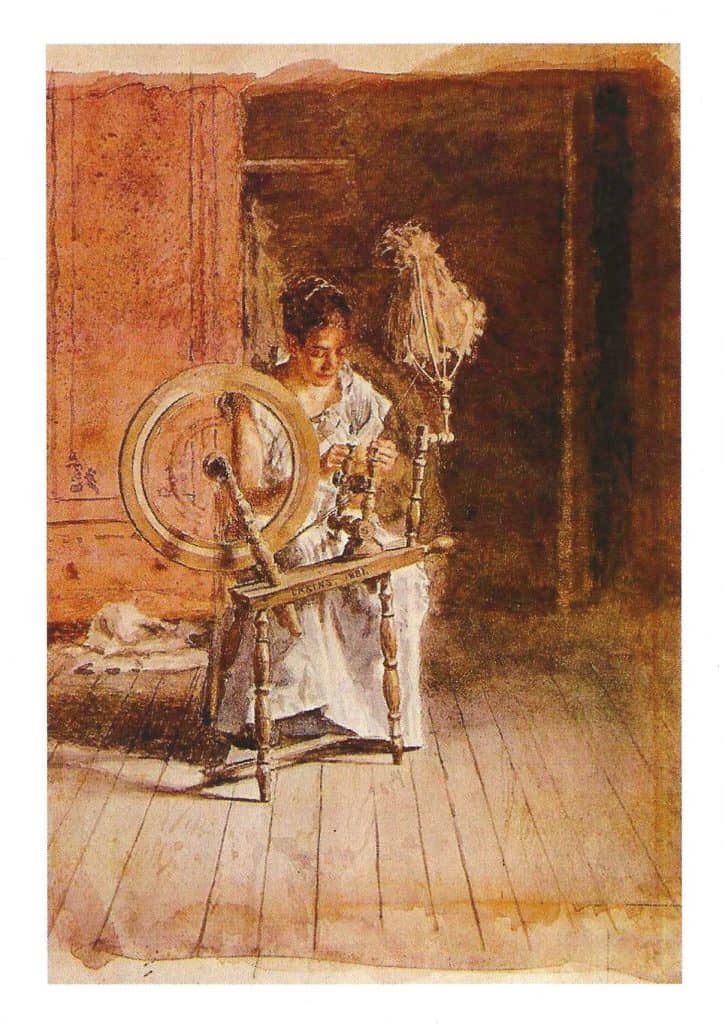

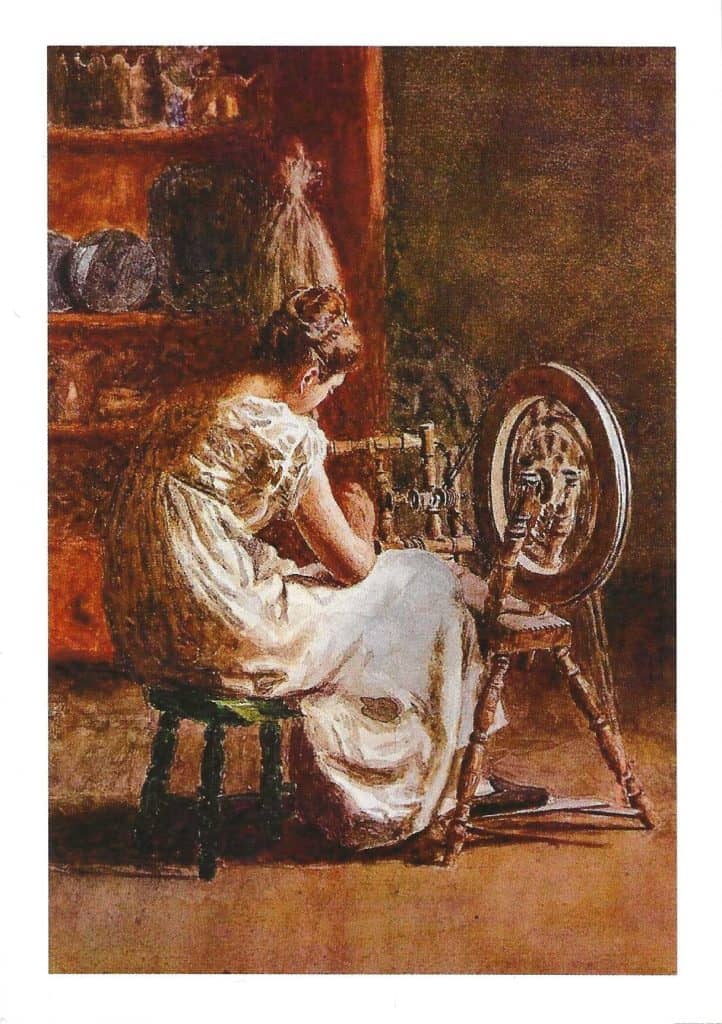

Spinners

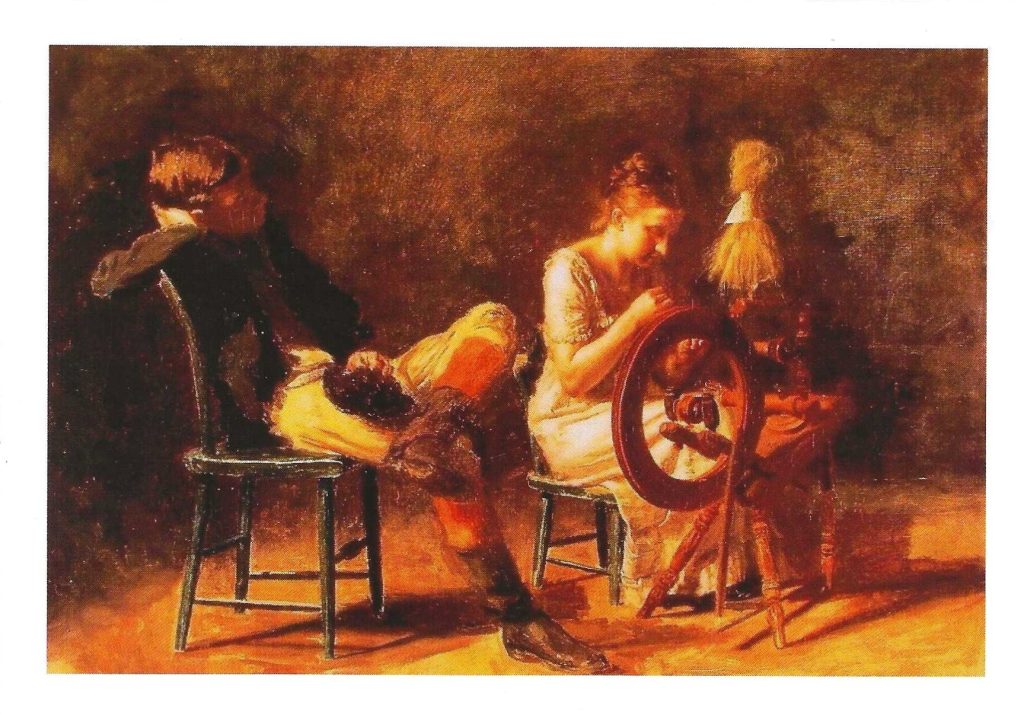

In 1881, a year in which Eakins painted twelve major pieces, Spinning, a relatively small work of only 11” by 8” was the first. It soon attracted the attention of family and friends, and he was encouraged to repeat his effort. Homespun was next. In it a young woman is seen seated on a green stool, attentively engaged in making yarn at a spinning wheel. She is dressed in a white garment that may be a bit outlandish for a work-at-home chore. Her focus is directed entirely on her task.

Spinning never left the family. It became a favorite of Mrs. John Randolph Garrett, Sr., a niece of Eakins’ wife, Susan Macdowell Eakins who died in 1938.

The spinning wheel phase of Eakins’ career ended here. The first appeared in 1876 when he completed a charming piece entitled In Grandmother’s Time, that is now in the Smith College Museum of Art in Northampton, Massachusetts. The second, entitled Seventy Years Ago, shows an elderly woman doing handwork sewing with a spinning wheel in the background. The third and last, The Courtship, was done in 1878. It shows a rather debonaire young man sitting with an equally attractive young lady who is working at a spinning wheel.

The Courtship is currently in the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, in San Francisco, California. A “study” for The Courtship, that is 11” by 17” came to auction in 1983; it sold for $80,000.

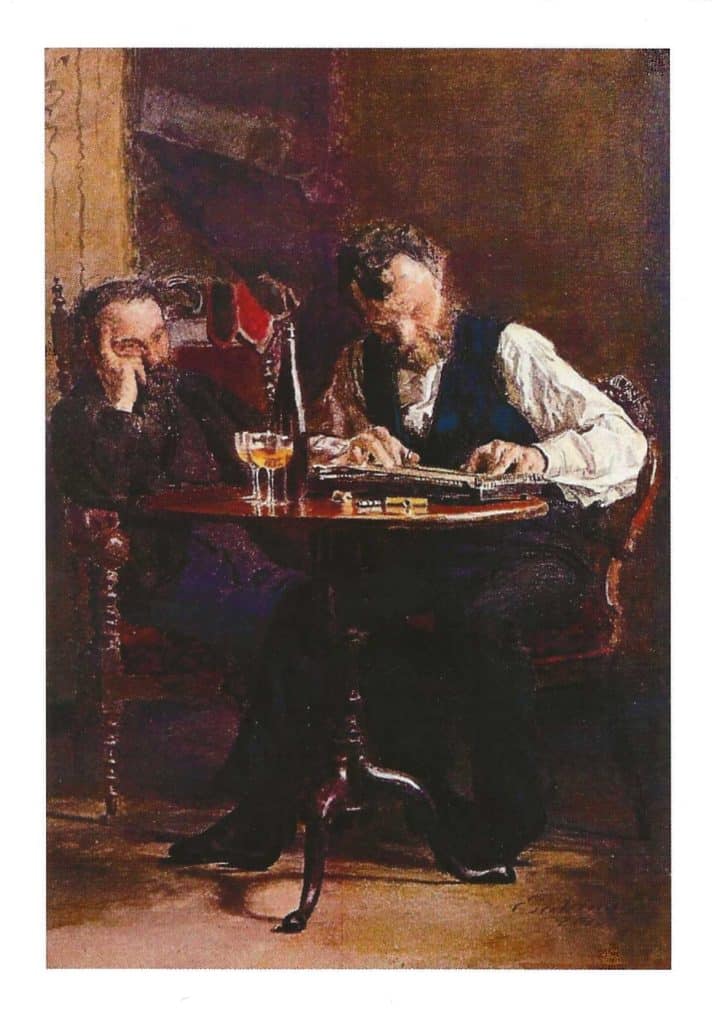

Musicians

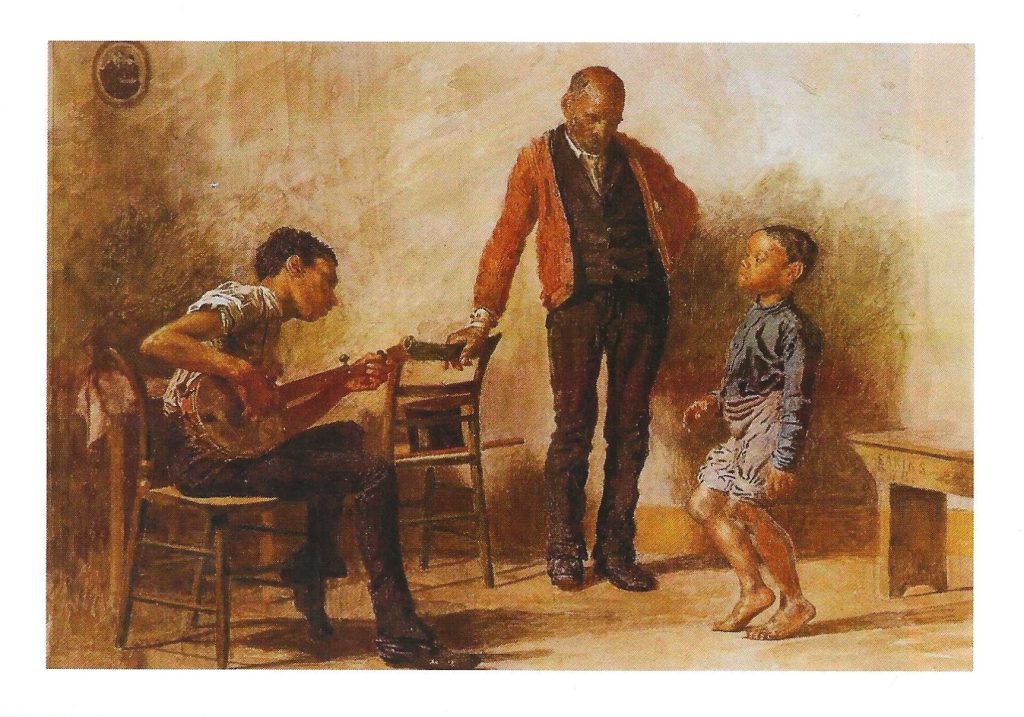

This watercolor shows three male figures of different generations playing and responding to music. In the background (upper-left corner) a framed copy of the famous photograph of Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad suggests that the three figures are an emancipated family, and their relationship has gained solidity through music.

This watercolor earned Eakins his first award, a silver medal, at the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association exhibition in Boston in 1878.

Eakins may have been the first to feature a zither in a painting, his The Zither Player, from 1876 was a watercolor on paper that is now at the Chicago Art Institute.

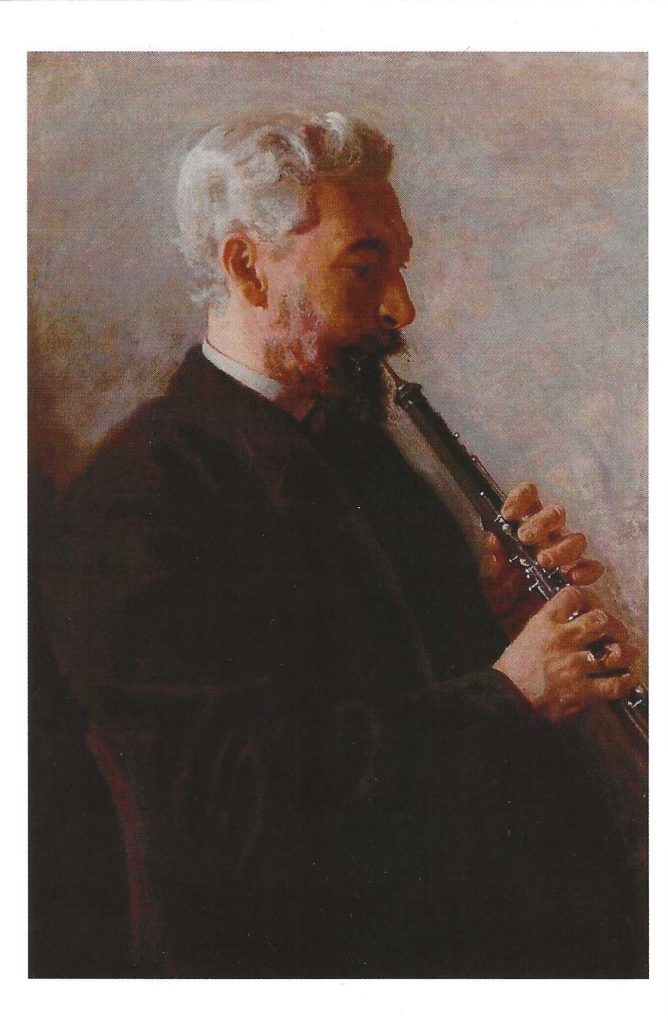

The Oboe Player of 1903 is a portrait of Dr. Benjamin Sharp. Sharp was born in 1858 and began his studies at Swarthmore College receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1878. He then went on to earn a master’s degree and a PhD at the University of Pennsylvania before going to Europe for additional study at universities in Berlin and Leipzig and the Zoological Station in Naples, Italy. His achievements in a lifetime were extraordinary; he earned two doctorate degrees (the second in zoology), became a professor of zoology at the University of Pennsylvania and was an accomplished musician.

Sharp’s skills as an oboist earn him a seat with the Philadelphia Symphonic Society, which later became the Philadelphia Orchestra.

In addition to his teaching duties, Dr. Sharp participated in four discovery expeditions: first to the Caribbean Islands during the winter of 1888-1889, then twice to the Arctic on expeditions with Captain (later Admiral) Robert Peary. In 1891 he was the chief zoologist on Peary’s first Arctic expedition, and in 1895 he returned to the Arctic aboard the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear. His forth such adventure was to the Hawaiian Islands in 1893.

The Oboe Player, 1903, oil on canvas is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Eakins painted his last significant portrait about 1903. The subject was the Rev. Denis J. Dougherty, who later became a Cardinal and the Archbishop of Philadelphia.

His very last portrait, in 1910, was of Edward S. Buckley, a painting that brings a sad end to an otherwise stellar career. The portrait was destroyed: according to Buckley’s daughter, “It was so unsatisfactory that we destroyed it, not wishing his descendants to think of their grandfather as resembling the portrait.”

**

The postcards seen with this essay are from a collection that is used to teach art history in a local community college. It is regrettable that no captions or publisher identification is available.

I had not heard of this particular artist but it seems he was very talented. I don’t think that I’ve

seen another postcard with a zither in it either.