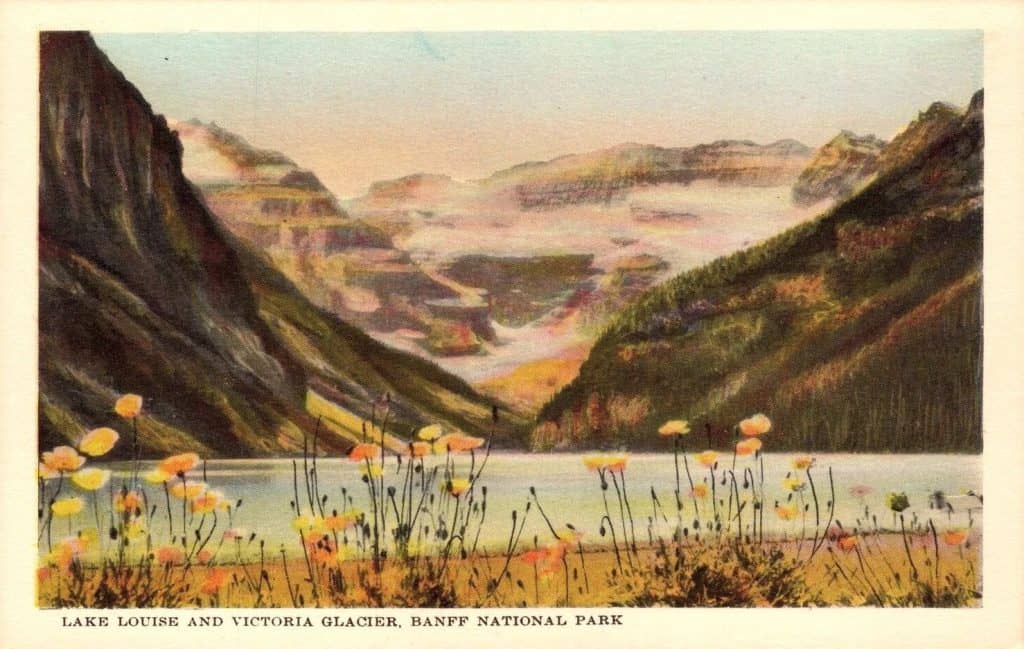

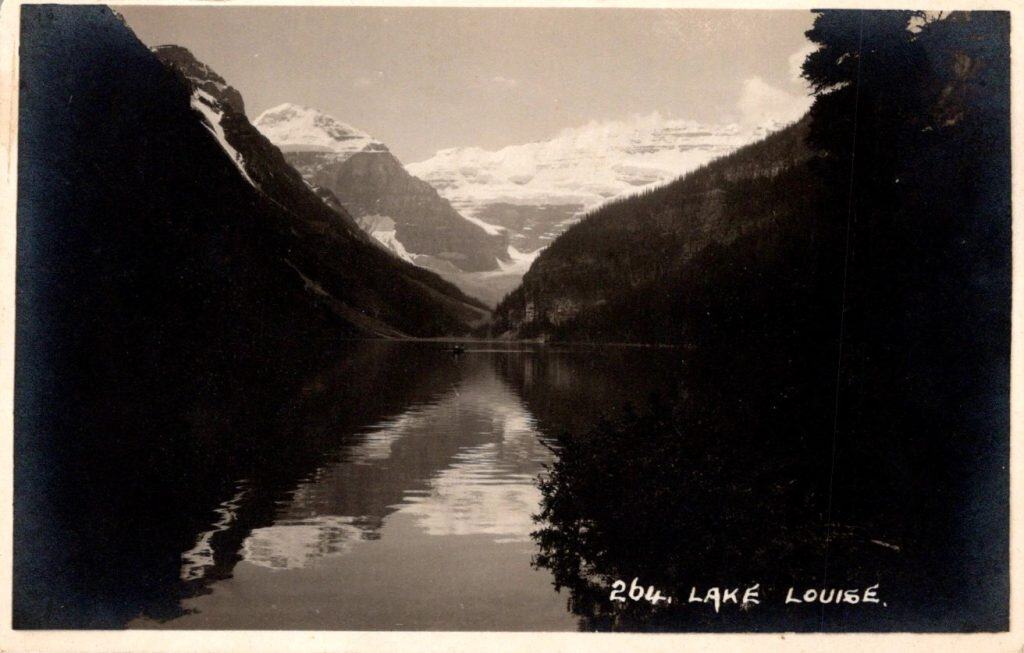

When you visit the glacier lakes in western Canada, it is the blue water that is most memorable. Wait, the water is not quite blue, it is turquoise or aquamarine. Some people call it peacock blue, others call it cobalt. But, no matter what blue it is, it is memorable. And, we know why!

As glacier ice melts, the meltwater (H2O) has something called Glacial Silt suspended in it. That substance is also call “rock flour.” Rock flour is an extremely fine sediment created by the erosion of glaciers and when sunlight is reflected off it, the light is in the “particular” blue wavelengths, resulting in the water’s striking blue hue. Also, the angle and intensity of sunlight play significant roles in enhancing the blue appearance of the water.

Victoria Glacier named for Britain’s Queen Victoria in 1897, is in the Canadian national park at Banff, Alberta. It is a prominent glacier among five others: Bow Glacier, Crowfoot Glacier, Hector Glacier, Saskatchewan Glacier, Vulture Glacier, and the Wapta Icefield. The Victoria Glacier is just north of Lake Louise as seen on the postcard above and is the major water source that feeds the lake.

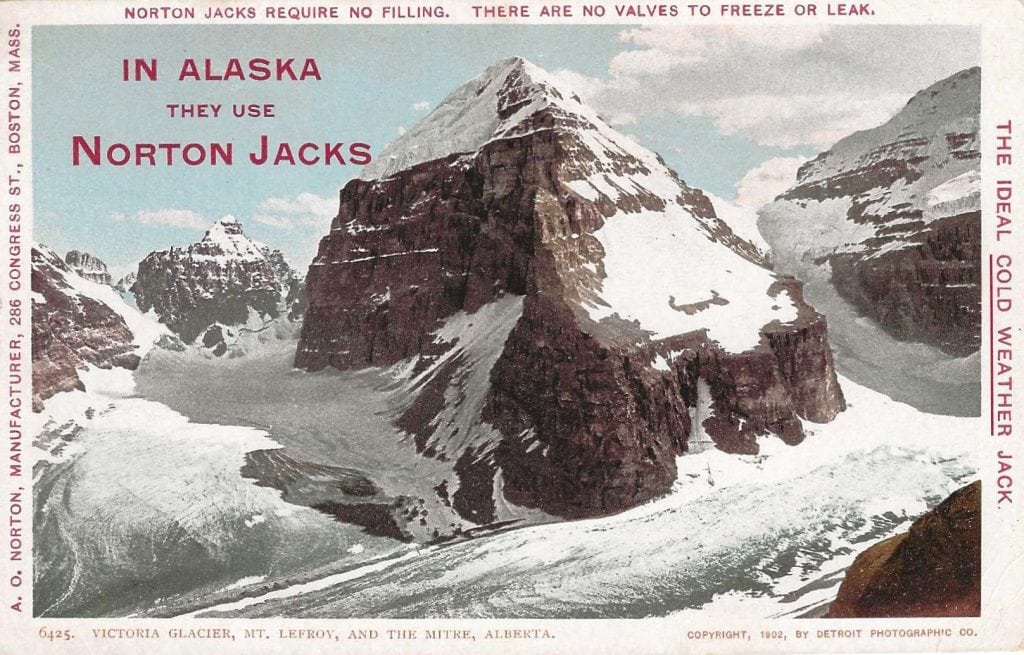

The card that follows is an advertisement for A. O. Norton. The Arthur Osmore Norton Company was a manufacturing concern established in Canada around 1886. Although Norton was a Canadian, he had family and business ties in Boston. Known primarily for his railroad construction jacks, he gained a considerable reputation for a jack design known as a “sleepers.” Norton’s sleepers jacks were manufactured in Boston, but also in Coaticook, Quebec, (a small town 100 miles east of Montreal) and Moline, Illinois. The over-print message clearly states … “In Alaska they use Norton Jacks.”

Detroit Photo #6425 (© 1902) with a splendid wintertime photo of Victoria Glacier (foreground, left), Mt. Lefroy, (center) and The Mitre (left center background) – all in Alberta, Canada.

Not to belabor the point, but all four edges of the card carry text. Some important, some perhaps not important. The text on the left edge reads that the product being advertised is manufactured by A. O. Norton. By reading across the top we learn that Norton “jacks” require no filling, and they have no valves. On the right edge we see that Norton “jacks” are ideal for use in COLD WEATHER. Along the bottom edge we can see that the illustration is Victoria Glacier, Mt. Lefroy, and The Mitre, [in] Alberta.

All this seems strange. Why is a Boston manufacturer advertising his “jacks” in Alaska using Canadian mountains and glaciers view cards. Is this a “neener, neener, neener” suggesting that Alaska has no beautiful scenery that could accompany a cold weather construction product?

Mount Lefroy is a mountain on the North American continental divide. Along the border of Alberta and British Columbia. It is presented well on the card above. The mountain (actually, an outcrop) was named in 1894 for Sir John Henry Lefroy, an astronomer who had travelled widely in Canada taking meteorological readings and recording magnetic observations.

The mountain is the site of the first fatal accident in modern mountaineering in Canada. In 1896 during a failed summit bid, a noted climber, Philip Stanley Abbott, slipped on rocks after just coming off an icy section and plummeted down the rock face to his death.

The first successful ascent was made in 1897 by a team of nine.

The Mitre is a mountain summit that rises to 9,350 feet in Banff National Park. It is situated at the head of the Lefroy Glacier (later Victoria Glacier) and was named due to its resemblance to a Bishop’s mitre. The first ascent of The Mitre was made in 1901.

What is most pertinent to the image is that the glacier, Mt. Lefroy, and The Mitre are approximately 1,775 miles from the nearest Alaskan site where Norton Jacks could be purchased or used.

***

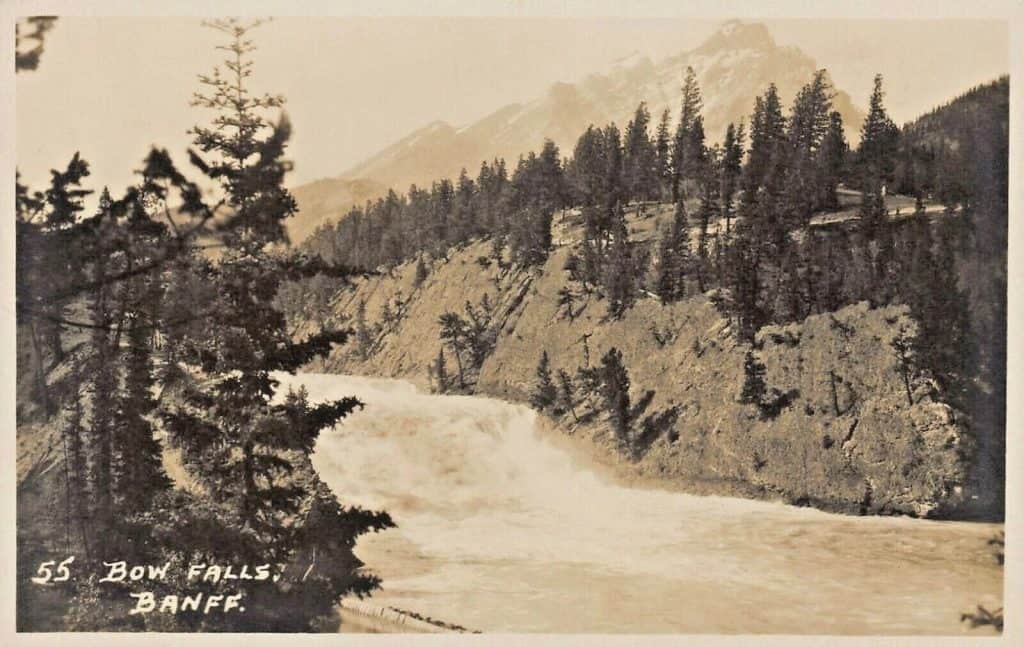

Postcards of Canada’s most beautiful sites are plentiful. One manufacture who produced some of the most collectable cards was Byron Harmon. Harmon created over 6,500 photos in the Canadian Rockies. He was born in Tacoma, Washington, in 1876. He started his career as the proprietor of a photo supply store, but in 1903 he moved to Banff, Alberta, and stayed. Over the next 30 years Harmon became a leading citizen of Banff, founding the local Board of Trade, the Rotary Club, and serving in municipal government.

***

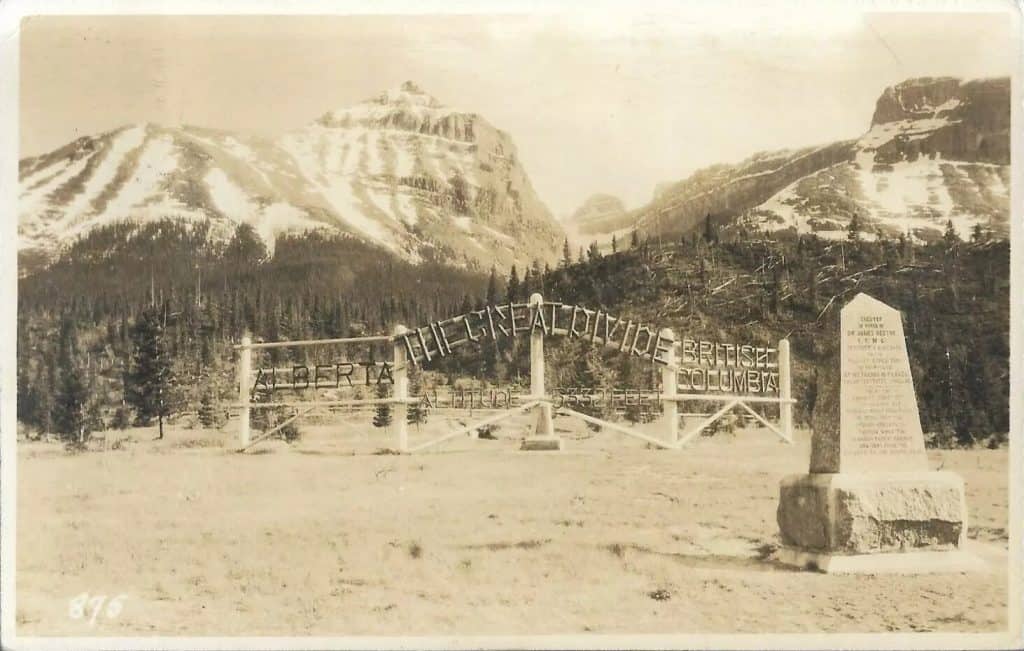

Other Harmon postcards of Lake Louise, Bow Glacier Falls, and the Great Divide follow. Each is mentioned in the text.

The North American Continental Divide, also known as the Great Divide, is the hydrological boundary line that runs from Alaska and western Canada and the United States, down into Mexico and Central America.

There is no obvious separation point, but the line separates watersheds that drain into the Pacific Ocean from those flowing toward the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, and Arctic Ocean.

When I was a girl of nine, and I stood with one foot on the western half of North America and my other foot on the eastern half, my father explained it to me by telling me to imagine a raindrop falling on the line. If that happened one-half the drop would flow into the Pacific Ocean and the other-half would end up in the Atlantic Ocean.

I don’t remember asking my dad questions. It was simple enough to understand. I guess the concept is clear; I’ve remembered that lesson for more than 50 years.

Thank you Kaya for your inciteful thoughts and views of our Canadian Rockies in Alberta. Many postcard dealers stocks are filled with mountain scenes (Switzerland, Canada, France, Italy and more – but we tend to bypass these cards and potential stories that can be told.

Well done for enlightening us on the common, but sublime. Hope you stay in Canada. Image courtesy Town of Banff website – Landmarks and Legacy.

So interesting We all remember things our fathers told us. Lovely country as is my homeland Scotland and Australia where home has been since 1962.

I would think that Norton Jacks was using the picture of a glacier and mountain, and referring to Alaska, to drive home the message that its jacks work in even the coldest weather. The fact that the image wasn’t actually of an Alaska scene was definitely unfortunate, but the average person out east wouldn’t have been too clear on how far Alberta was from Alaska anyway, if they noticed the discrepancy at all. The cards would have been distributed to customers wherever they were. Everyone wanted pictures of interesting places for their postcard albums – as many postcards were sold… Read more »