Frank Hamilton Spearman, born before the American Civil War, is mostly forgotten. Today, his railroad stories, his western romances, and his late-career novels are as readable today as they were over a century ago. He never worked for a railroad himself; however, his vivid portrayals of railroading life captured the imagination of readers and filmmakers alike. It could be said that he was unique in the ways he created heroic fiction.

Spearman was born in 1859 in Buffalo, New York. He spent his boyhood in Wisconsin where he attended Lawrence University in Appleton but was orphaned when he was 15 and forced to leave school to work in his brother’s Chicago grocery store. He married in 1884; he and his bride were both 26.

Frank was always frail in health and was able to find relief in the small town of McCook, Nebraska, where he lived for eight years and worked as a bank president. It was in McCook that he chose to write. Mr. Spearman frequently asserted that writing helped him regain his health so writing became something he did every day. He drew inspiration for many of his characters and settings from his friends, clients, and neighbors. His early stories reflect the transformation of the prairie from untamed frontier to modern society.

Shortly before 1910, Spearman and his wife Eugenie (nee Longergan) lived on Wesley Avenue in Evanston, Illinois. They had four sons: Clark, Eugene, Frank, Jr., and Arthur. The Spearman family moved often and finally settled in California in 1915.

Spearman’s railroad short stories occupy a niche of their own in American fiction. Two of his early novels, “Held for Orders” (1901) and “The Nerve of Foley” (1900) were still in print as late as 1937.

In 1916, Avila was a new, private Catholic university in Kansas City, Missouri. Sponsored by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, it offered bachelor’s degrees in several disciplines, however the most coveted degrees were granted by the English and Foreign Languages and American Literature departments. In October 1916, the fall classes were well underway when an American literature professor brought a friend to his Wednesday morning class to be the first in a series of lecturers who would talk about their latest novels.

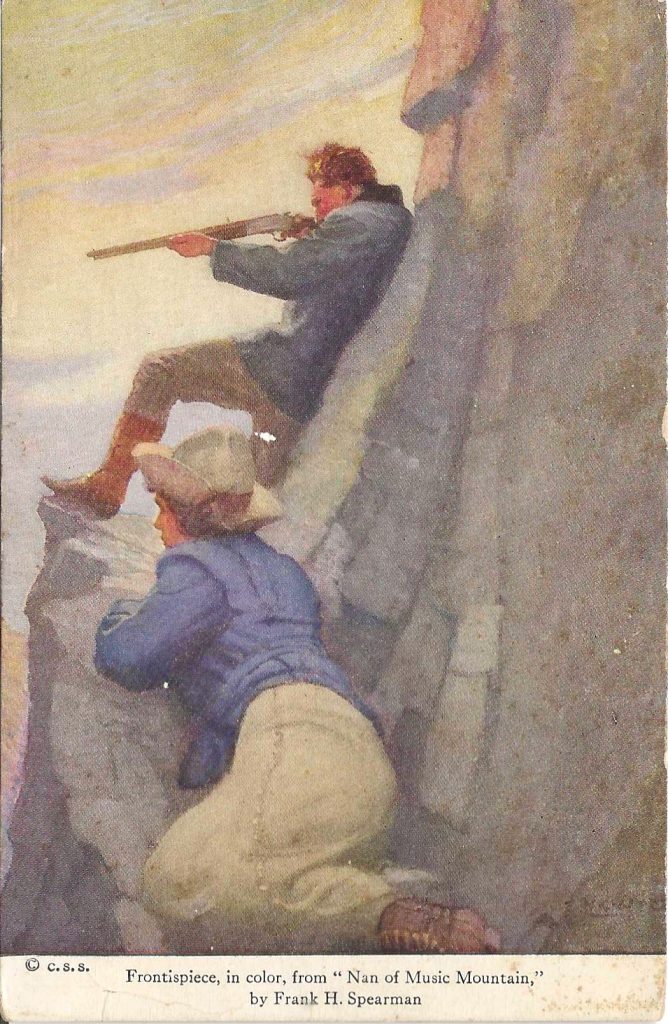

Frank Spearman had just published his newest book, “Nan of Music Mountain” and he was pleased to talk about his work as a novelist that had brought him both wealth and fame for more than a decade.

The new novel had found much favor with the critics, and especially with two Hollywood film makers George Melford and Cecil B. DeMille.

When Spearman invented the character of Henry de Spain (played in the movie by Wallace Reid) his idea was to have his hero be a determined individual who would not rest until he found the man who murdered his father. He becomes sort of an outsider with Duke Morgan’s gang, an unruly clan of cattlemen and outlaws. Nan (played by Ann Little), daughter of the head of the clan, secretly loves Henry and when he is wounded in a fight with the Morgan clan, she helps him escape. This angers her father, and he declares that she shall marry her cousin. Nan dispatches a message to Henry for assistance, and he is successful, but through their trials Nan learns that her father was the killer of Henry’s father. When she and Henry return to her father to learn the truth, her father reveals the truth. It took some time to reach an understanding, but it came and so did forgiveness. Henry and Nan are married.

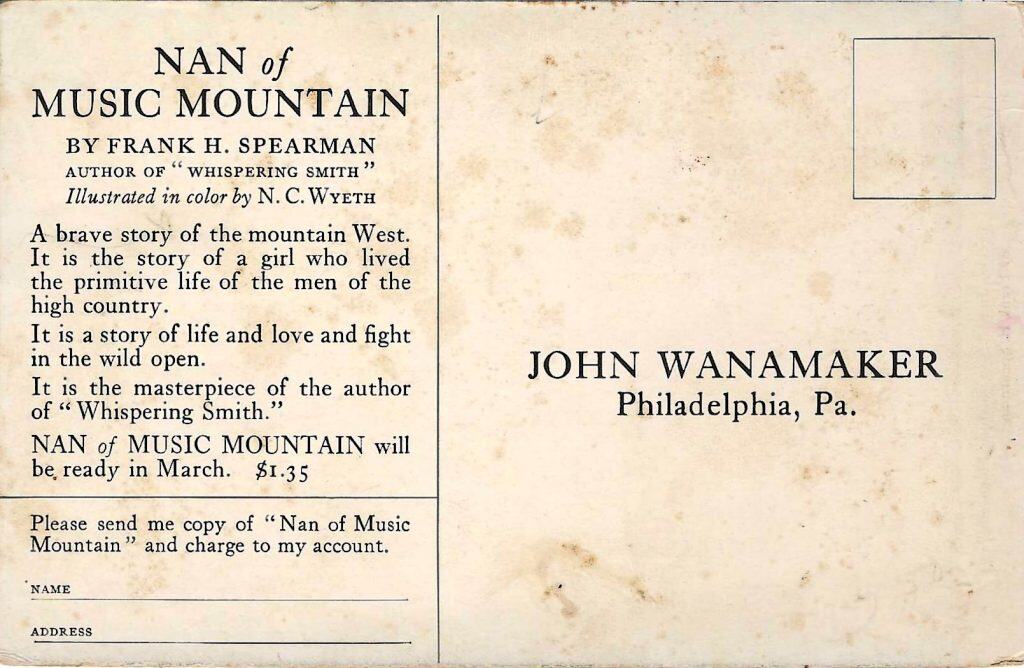

The movie is totally compliant to Spearman’s novel. Originally published by Charles Scribner’s Sons of New York in 1916. The text was illustrated in color by N. C. Wyeth. If you had established credit with the Philadelphia department store, John Wanamaker, you could have a copy mailed to you for $1.35 that would be charged to your account.

Spearman was a devout Roman Catholic whose beliefs are reflected in his twenty novels and dozens of short stories. His work earned him no less than three honorary doctorates and in 1935 he was awarded The Laetare Medal, the most prestigious award given to American Catholics, by Notre Dame University.

On Friday, December 30th or Saturday, December 31, 1937, newspapers across the country published Spearman’s obituary. He died in a Hollywood hospital on the 29th from “a stomach ailment.”

Tim Van Staden’s article are always good. Thanks