In 1870, George A. Otis, a son of the great state of Massachusetts as part of his official duties at the U. S. Surgeon General’s office, edited the first of what would become a six-volume reference set entitled, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. It was a gigantic undertaking that compiled statistics and case reports from both the Union and Confederate armies. The first surgical report was titled, simply, “A.L.”

The information included in the Case of A.L. became the government’s official report of the events of April 14 and 15, 1865 – the assassination of the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln.

In a recent issue of The Civil War Monitor, distinguished author and historian Mathew W. Lively, M.D., of West Virginia, presented a fresh look at the autopsy of President Lincoln. Lively entitled his illustrated article, “It Was Good Friday” and presented a detailed account of events, personalities, and consequences of that Friday night and the following Saturday.

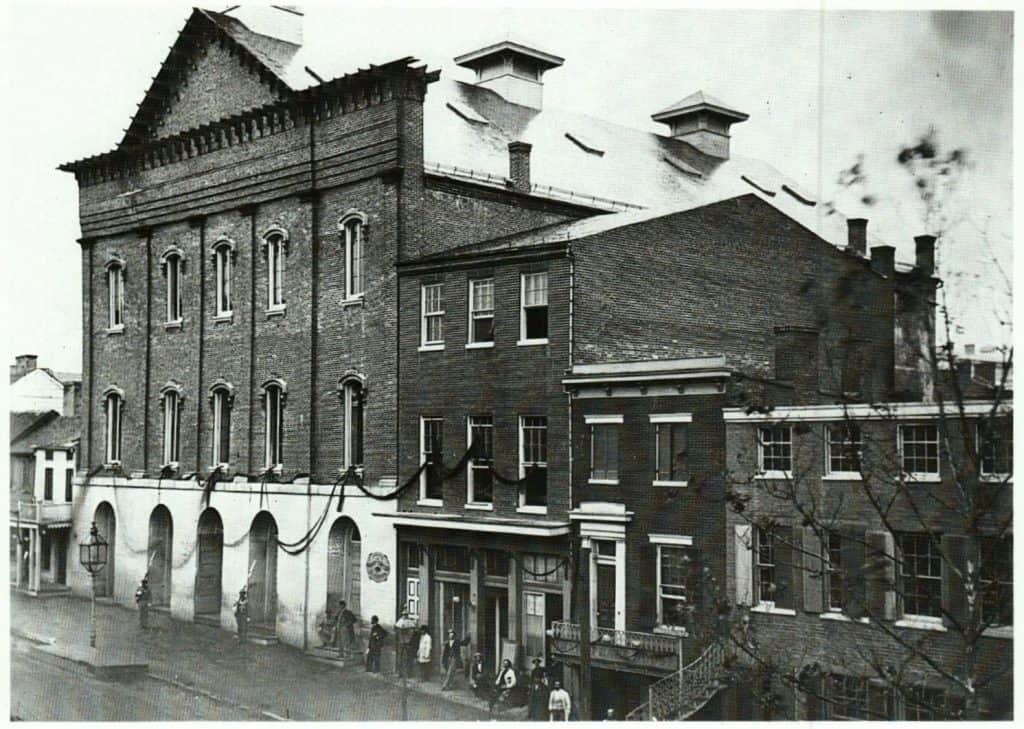

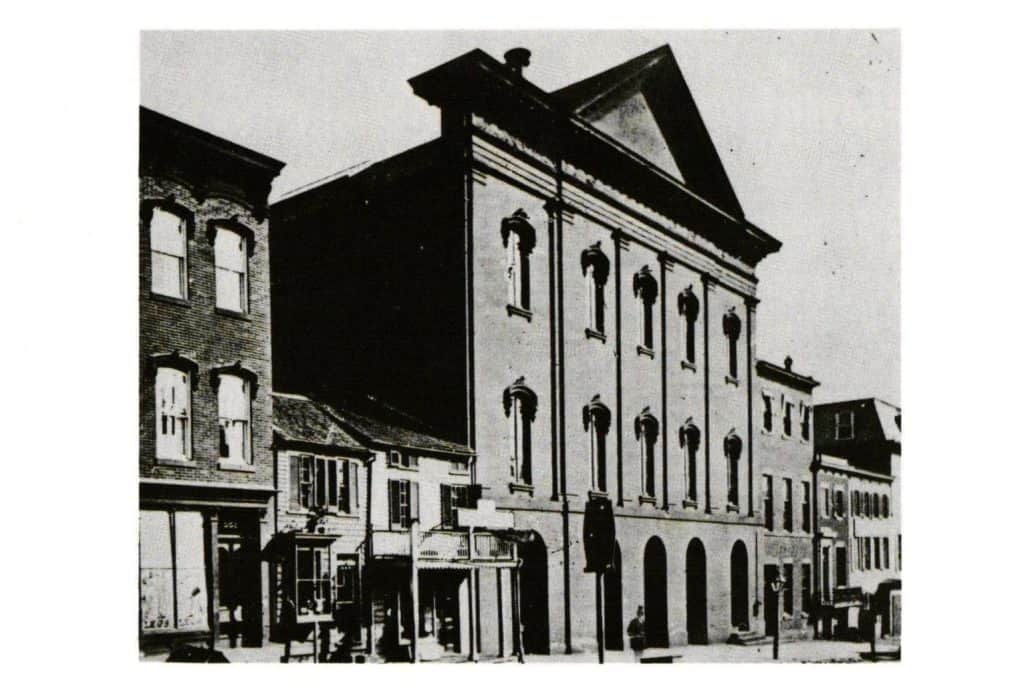

The event is remembered because it became an integral part of mid-nineteenth century American history. Even the newest scholars of American history know that John Wilkes Booth crept into the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre that April night during a performance of the play, Our American Cousin, and shot the president in the back of his head with a .44-caliber Derringer pistol.

The consequences of the assassination have been topics of study and historical “second-guessing” for decades. If Abraham Lincoln had not been assassinated, post-Civil War America might have experienced a more unified and stable reconstruction era. Lincoln’s leadership could have fostered smoother integration of freed slaves into society. He may also have helped to rebuild the South and potentially reduce racial tensions. His continued presidency might have advanced civil rights and social reforms earlier. But such speculations serve no purpose.

***

As PCHistory readers know, postcards came about as a commodity over forty years after the 1860s and many postcards relevant to the assassination are simply wrong. They show Ford’s Theatre decades after the 10th Street façade was renovated. There are contrived scenes that show the President and Mrs. Lincoln as the only occupants of the Presidential Box, and dozens of similar scenes show Booth shooting Lincoln in the right side of this head. There are even numerous photographs of “wax-museum” exhibits. Please do not rely on postcards as primary sources in any research you undertake. Examples:

Sadly however, many of the personalities who witnessed the assassination and the autopsy that followed on Saturday afternoon have been forgotten. There were many. It is here that Dr. Lively excels in his research and writing.

***

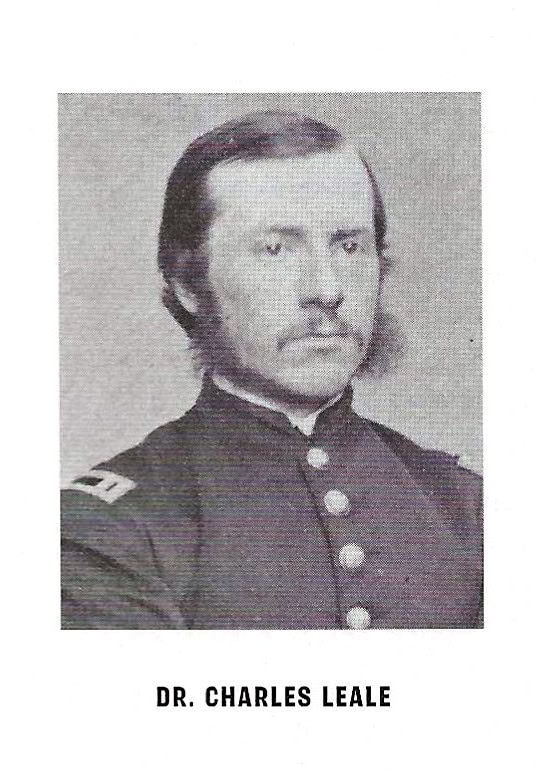

It is fortuitous that many of the personalities immediately recognized that history was in the making, and they made detailed notations. It began with a young Dr. Charles Leale.

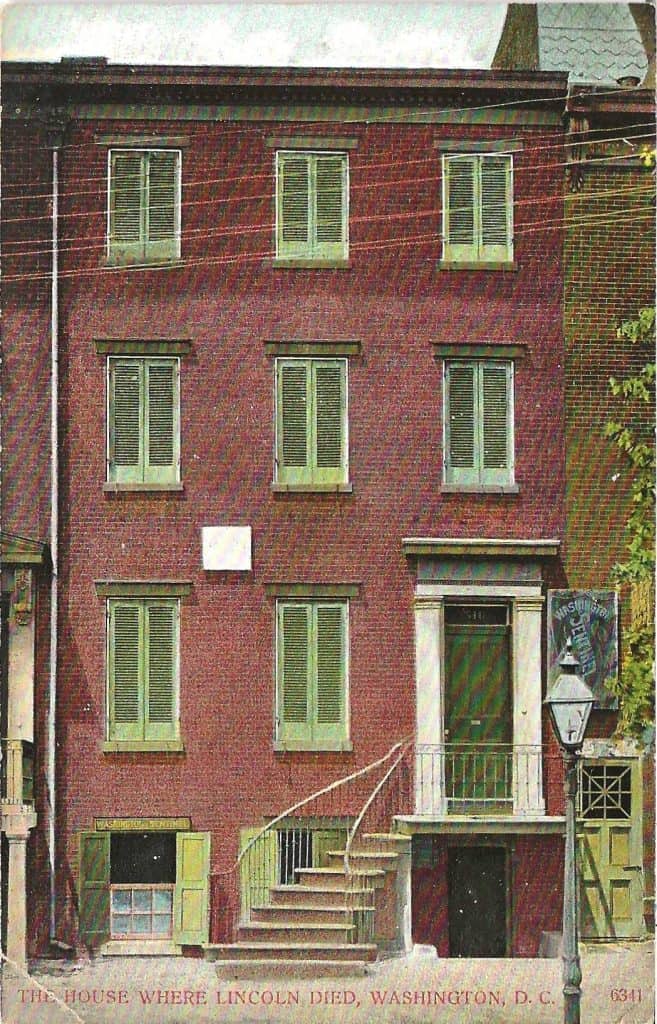

Shortly after 10:30 PM, the shot that killed the President echoed throughout the theatre. The chaos and noise prompted Leale, only six weeks out of medical school, to run to the box hoping to be helpful. When other physicians arrived it was soon decided to move the President to a more suitable location. As it played out, the Peterson boarding house across the street was the destination and ultimately the death site of the President.

At the Peterson house the physicians laid Lincoln on a bed in a small room in the back of the house. He was examined for wounds, but it was obvious that the one to his head was the only one, and it would be fatal. Dr. Leale ordered that Lincoln’s legs be wrapped in blankets.

A silent vigil went through the night until 7:22 AM, Saturday when the President died from the bullet wound.

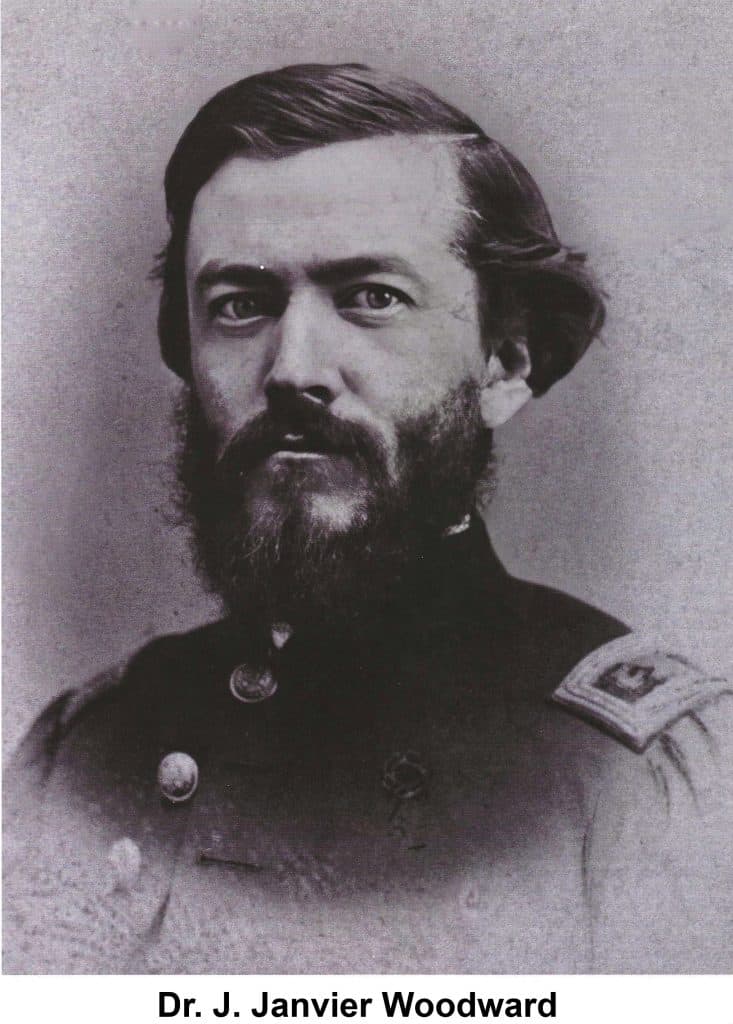

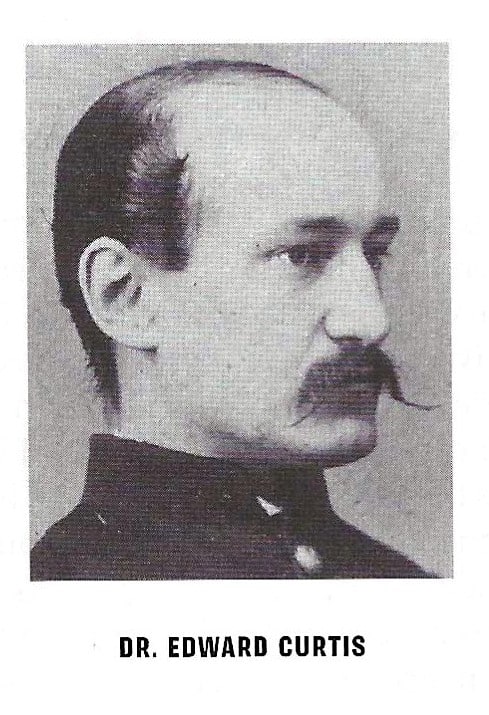

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Surgeon General Dr. Joseph K. Barnes determined that a postmortem examination would be required. Barnes directed that Dr. J. Janvier Woodward would perform an autopsy back at the White House.

The body was moved to the White House by a contingent of the cavalry in a makeshift casket and the autopsy commenced at 12 noon, led by Dr. Woodward and assisted by Dr. Edward Curtis.

The autopsy is described in great detail by Dr. Lively, including the use of silver and Nélaton probes to locate the place in the brain where the bullet was lodged. He also describes the process of how the President’s brain was removed, measured, and weighed. And finally, mention is made about how the physicians complied with Mrs. Lincoln’s request for a lock of the President’s hair.

Others who witnessed the autopsy are named by Dr. Lively, but none served in a capacity other than as a witness.

The official end of the investigation came late in 1865 with the completion of the report by the “Acting Assistant Surgeon C. S. Taft.”

The history that Major G. A. Otis compiled and published in 1870 is still available at reasonable prices in many used bookstores across the country. It is a fascinating story, but it is a dreadful read that includes dozens of statistical charts and pages of technical/medical terms.

Wowza. The sometimes gruesome past revealed by Ray Hahn in his typically consumate writing style.

Yet another very interesting PCHistory read! Thanks!