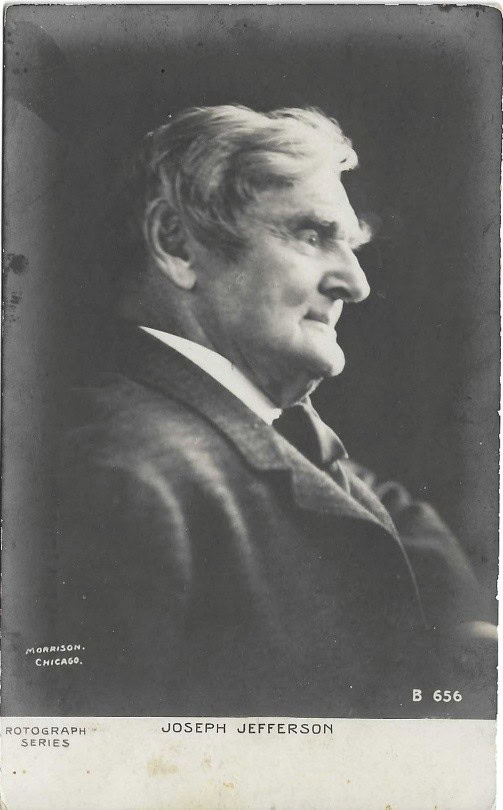

Joseph Jefferson was born in 1829 in Philadelphia. He was the son and grandson of the Joe Jefferson line of American actors. He made his first stage appearance at age three when he appeared in the melodrama Pizarro, where the contrast between the (evil) Spanish conqueror Pizarro and the (noble) indigenous Peruvians was sharply drawn.

Pizarro was one of several plays that used historical facts to criticize European greed. The play originated in Britain earlier but its appearance in America was well received.

Jefferson’s early years were hard as the family travelled from town to town, doing nightly performances and then moving on to another town and another theater. One of the few advantages for Joseph was that he learned stagecraft and developed a bond with other acting troupes.

His first success was in 1858 when he played the title character “Trenchard” in Our American Cousin during its original production at Laura Keene’s Theatre in New York. The play ran for more than 150 performances (long for its time) and Jefferson became well known as a comedian as well as an actor.

In 1861 the Civil War broke out. Because of the war, the theatrical industry collapsed, the country was in no mood for entertainment, and touring was dangerous and unprofitable.

Additionally, Jefferson’s wife, Margaret Clements Lockyer, who he had married in 1850, died that year. These two events affected Jefferson deeply and he abandoned New York, moving to Australia, where he acted in numerous plays and began to write.

Jefferson was on his return to the United States when he heard the news that Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated while in the audience of Our American Cousin. Suddenly the play in which he had starred not only became toxic, but since the murder was committed by fellow actor John Wilkes Booth (with whose brother Edwin, he had become friends) cast a deep shadow over his career. As a result, Jefferson changed his destination to England.

One of the stories Jefferson had in mind to adapt for the stage was Washington Irving’s 1819 story Rip Van Winkle. Several failed attempts at doing this are known, the first of which was in 1828, written by an unknown author.

Theatrical tastes were changing from melodramas to more substantial characterizations. In England Jefferson collaborated with the playwright Dion Boucicault, to re-tell Rip’s story on stage.

When the ink dried, Jefferson had managed to re-tell the Rip Van Winkle tale in a three-act play. He managed to preserve many elements of the tale but also added new scenes.

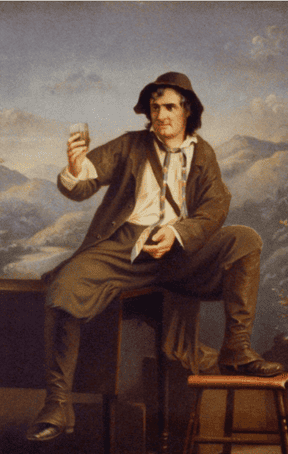

In the first act, Rip was still a lazy man from the Catskill Mountains of colonial New York whose drinking and other faults are the bane of his wife, Dame Van Winkle, who often scolds him for his laziness and drinking. Rip escapes his wife and heads into the mountains where he meets some mysterious veterans from Hendrick Hudson’s crew who are playing nine pins. They offer him liquor and he soon falls asleep.

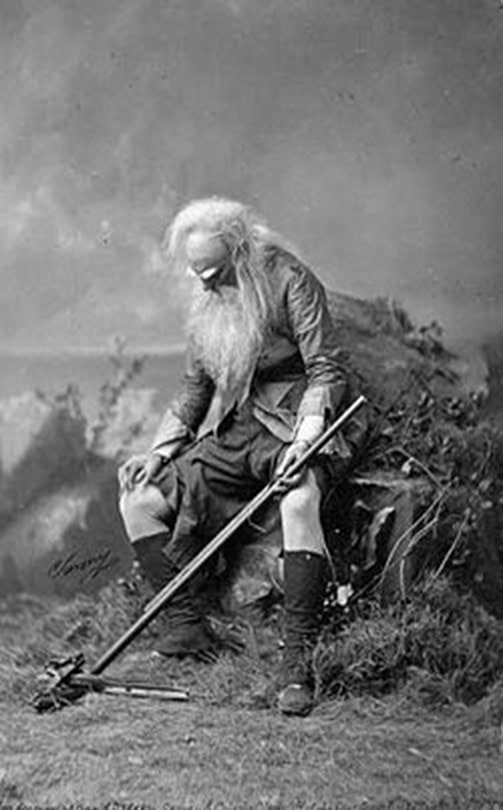

In the play’s second act, Rip wakes up from a 20-year sleep in the same place but discovers that it has been transformed by time. The politics have changed, there are new faces, and many of his familiar landmarks are gone. The second act ends as he meets his now adult daughter who recognizes him as her father.

The third act sees Rip reuniting with his daughter and discovers that his wife has died. He tells of his supernatural experience with the ghostly bowlers, which meets with skepticism from the villagers. Eventually Rip is accepted back into the community, but now as a harmless old man and a beloved storyteller. The play ends with Rip sitting peacefully smoking his pipe while contentedly recalling his past.

Jefferson’s Rip Van Winkle first appeared at the Adelphi Theatre in London on September 4, 1865. It was not an immediate success, in part because Jefferson’s acting overshadowed the play.

Jefferson built Rip as a character, not just a fable. As this was a stage play, Rip had emotional power that the printed page couldn’t deliver.

Jefferson modified the script by adding a villain, having Rip develop a warm father–daughter relationship that didn’t exist in the story, providing emotional scenes when Rip returned from his “nap,” and inserting pathos as well as humor to the mix.

Jefferson was not just the author, he was Rip. He was the American stage comedian of his era. His Rip Van Winkle became one of the most iconic roles in nineteenth‑century theater.

Jefferson never wrote again after he created Rip. He toured across the U.S., Europe, and Australia, and when silent motion pictures arrived, he took the play to them. The movie came to be seen as what people thought of as the original Rip Van Winkle tale and the Washington Irving story as some sort of offshoot.

Joseph Jefferson died in Palm Beach, Florida, in 1905, while visiting from his home, that he called “Orange Island” in New Iberia, Louisiana. When he was in Australia, he began to paint landscapes and continued doing that until he died. He was a member of the New York theatrical club “The Lambs,” and many other similar groups.

Jefferson is often remembered through his 1890 autobiography. He blended some charming theatrical nostalgia with some very select self‑mythology, which offered a vivid insight into nineteenth‑century stagecraft. It was filled with anecdotes of professional conflicts and artistic limitations that revealed much of the unknown Jefferson.

In 1968 the “Jeff Awards” were created in Chicago to honor him for his stagecraft and contribution to the theater arts. There are two categories: first for “Equity” work, and second for “Non-Equity” work. One notable award winner was Patti LaPone.