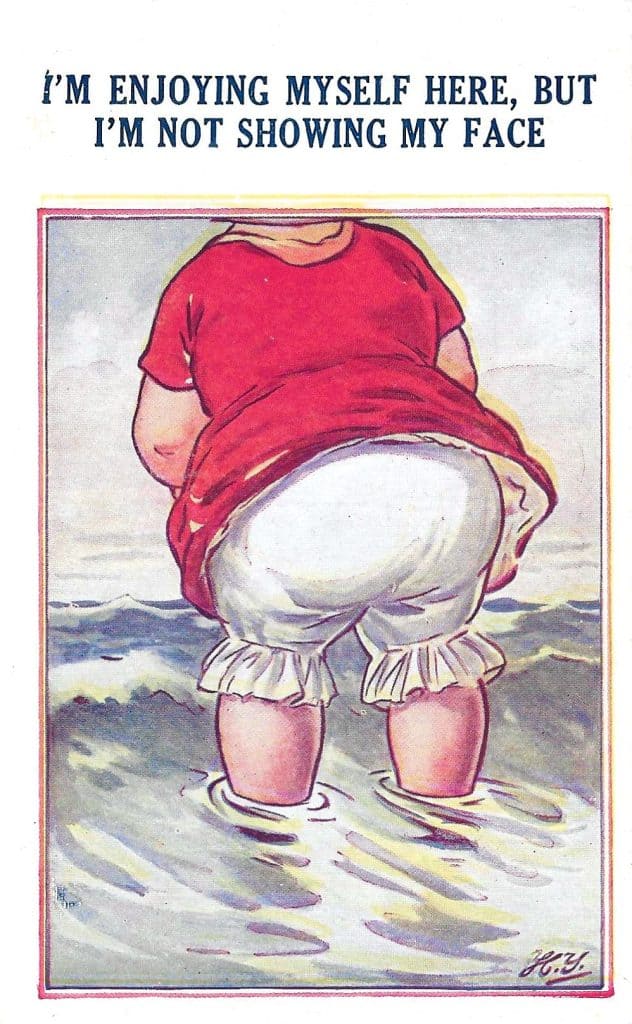

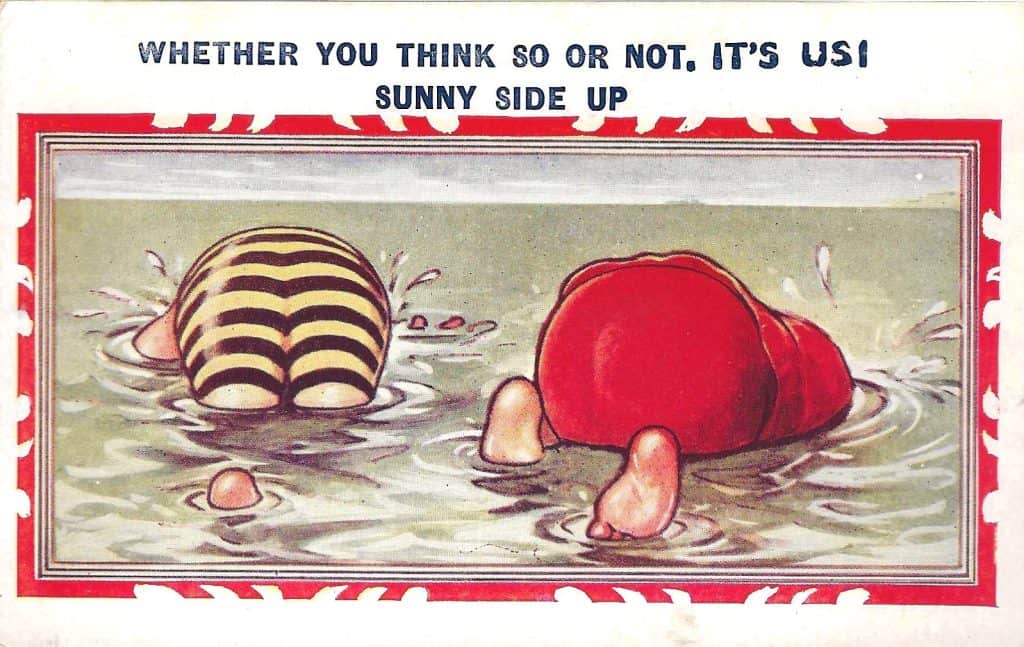

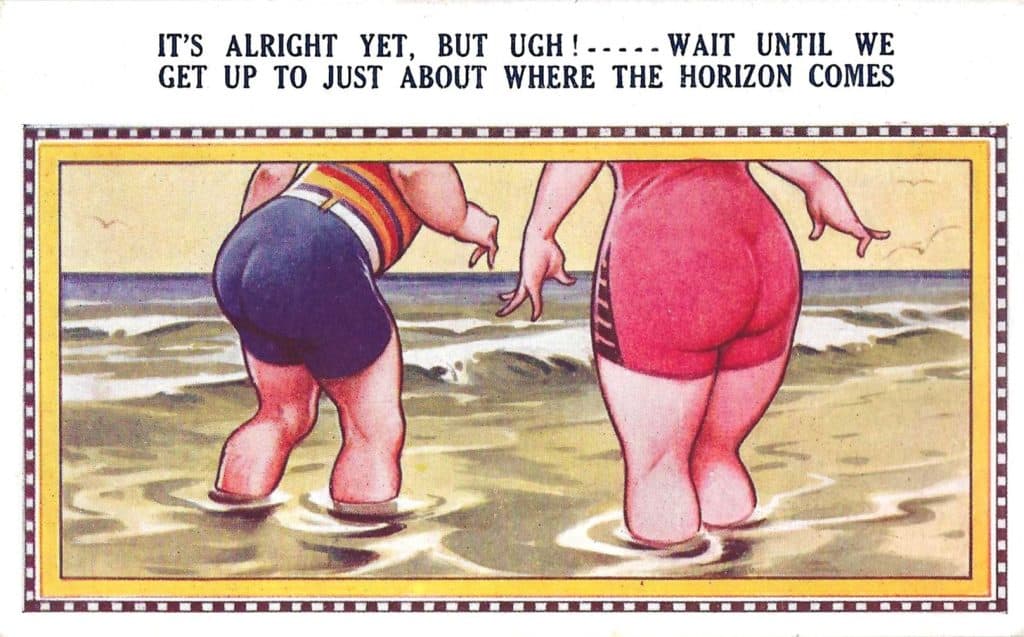

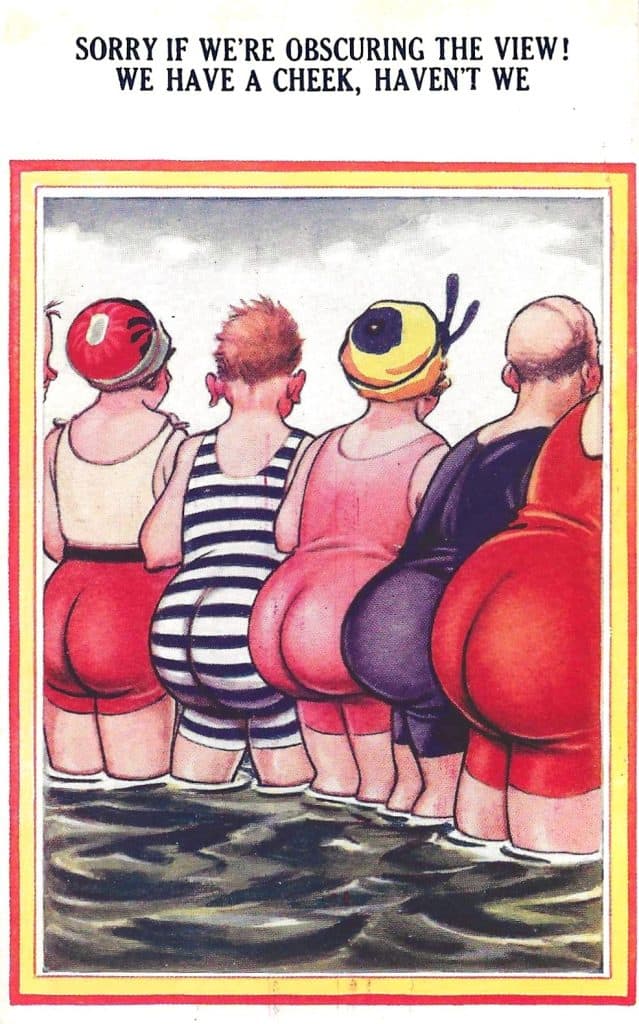

British seaside humor has a very particular flavor, and the “big bottom” joke is one of its longest‑running themes. By no means is it random, it comes from a mix of cultural history and a national taste for cheeky, harmless naughtiness.

A “big bottom” first appeared as a comic image in the late nineteenth century and soon became a tradition in saucy but safe humor. Knowing there is a trend brings us to the foundation of a lot of the U.K.’s comedic innuendo — jokes that are naughty without being explicit.

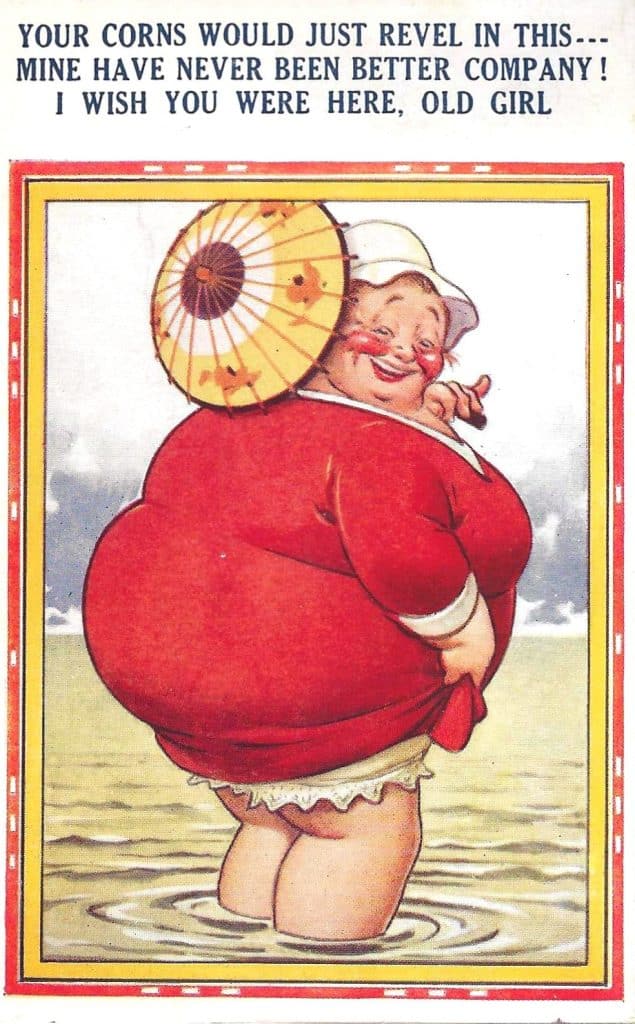

A large bottom is perfect for innuendo because it is sexy but not sexual, it allows people to laugh at something “rude” while keeping things family‑friendly, and it fits the British habit of laughing around sex rather than about sex. It is part and partial of the same tradition that produced Benny Hill’s shorts and John Cleese’s Monty Python films, and thousands of pantomime jokes.

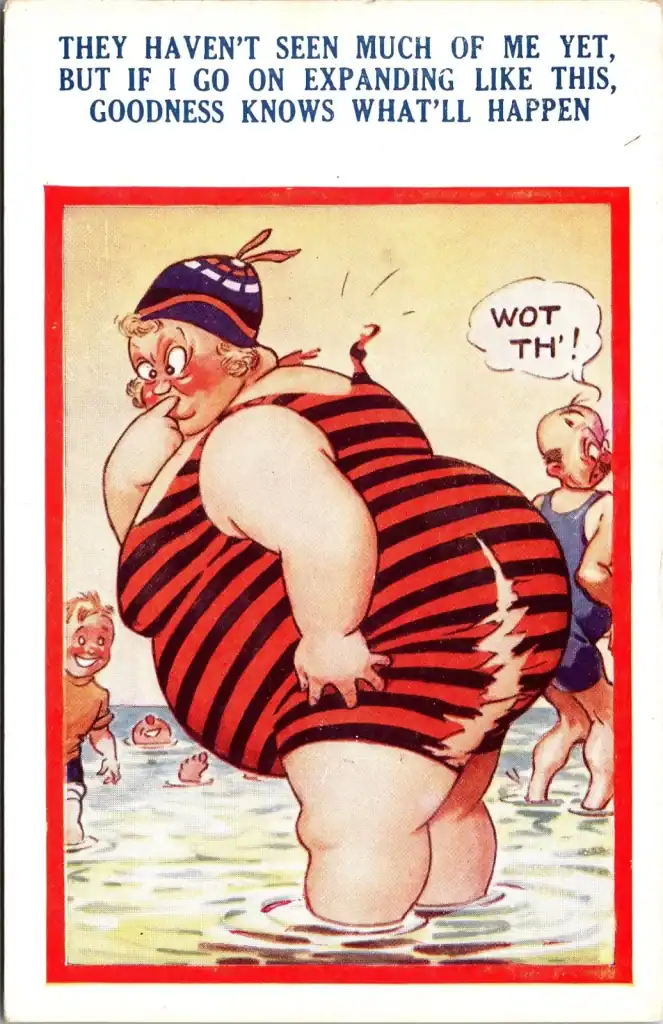

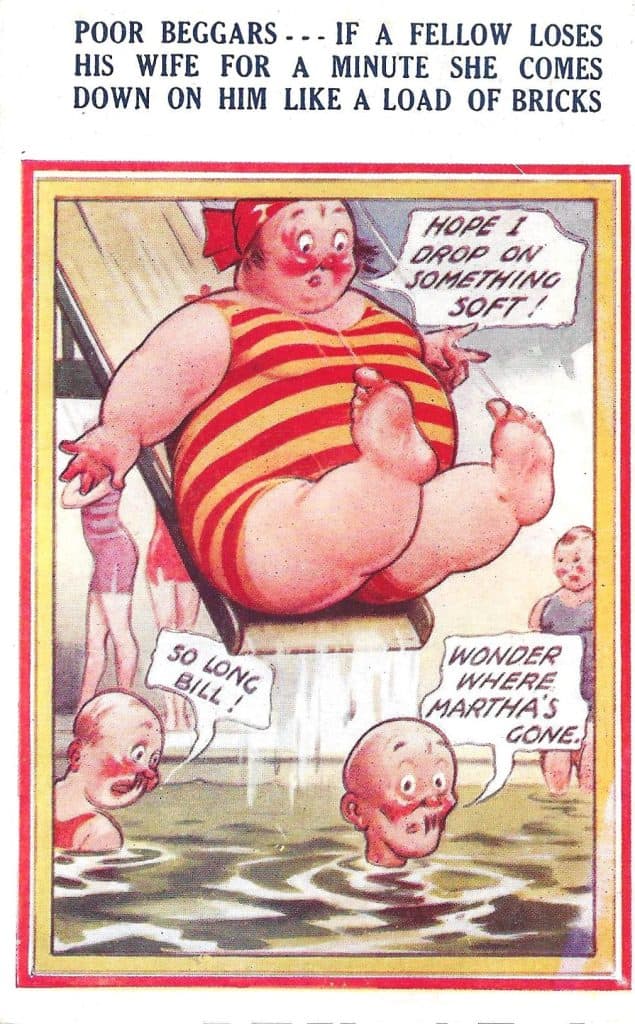

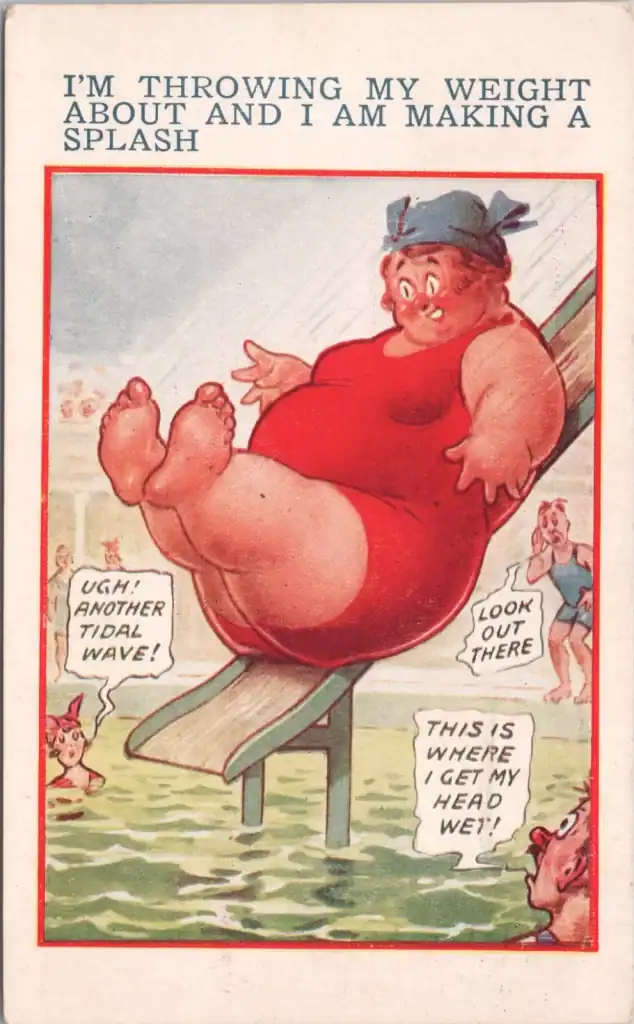

Artists by the dozen, Donald McGill, in particular took to the making of seaside humor postcards during the boom in the early twentieth century. McGill, whose exaggerated bodies — especially big bottoms, became models for other publishers like Bamforth to find artists who would imitate McGill’s success. McGill’s cards were mass produced, cheap, a bit risqué, and were perfect souvenirs for the working‑class holidaymakers to poke fun at themselves and each other. The “big bottom” became a visual shorthand for comic mischief.

Saucy humor sociologically has many elements, among them are exaggeration, prudishness, and a love of self‑deprecation – sort of a poke at the stiff upper lip folks.

The English more so than the Scots and Welsh often enjoy laughing at themselves. The big‑bottom postcard lets them say, “Well, aren’t we looking a bit ridiculous on holiday,” “Look at us stuffing ourselves with fish and chips,” or “No one here is taking himself too seriously.”

Consequently, most of the postcards gently mock the prudishness of the middle class and condone the loud, sunburnt, working‑class holidaymaker who sees no harm in “letting yourself go” on holiday. It’s humor that’s inclusive rather than mean‑spirited.

Not to be ignored is the fact that a big bottom is not the only exaggerated symbol of indulgence, gluttony, or carefree behavior. Other elements of cartooning often include oversized noses, tiny hats, or huge moustaches.

***

British seaside postcards have a surprising backstory, and the “big bottom” theme sits right at the center of it. The deeper you go, the more it reveals about British attitudes to sex, class, censorship, and even national identity.

For decades, saucy postcards were policed by local councils and the Home Office. Artists like McGill were actually prosecuted in the 1950s for “obscenity.” His crimes were “drawing large women bending over,” “husbands ogling other women,” and poking fun at or about underwear, corsets, and bathing suits.

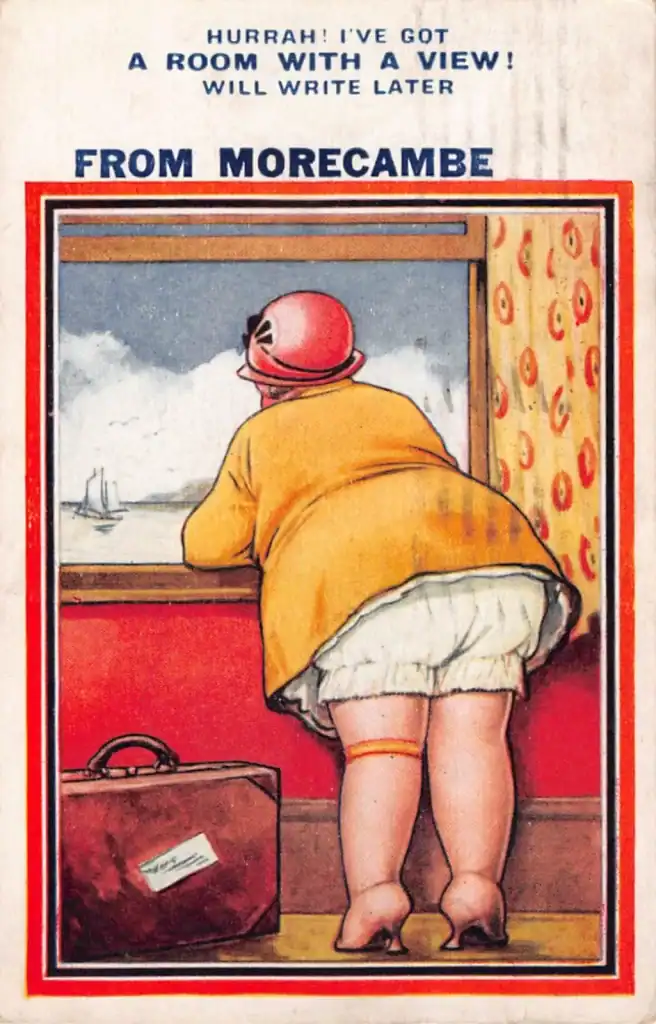

When the seaside became a “permission zone” where working‑class families could escape the city and relax their social rules by drinking, flirting, and participating in other silliness it was expected that the souvenir postcard would be the most popular item purchased in every curio shop along the strand.

It’s affectionate satire. The joke is: we’re all a bit ridiculous when on holiday, especially when wearing clothes you wouldn’t wear at home, making fun of middle‑aged couples or husbands with wandering eyes and wives with large handbags and larger personalities.

So, when did it stop? It hasn’t, however it did decline. By the 1980s and 1990s tastes changed, postcards would soon become old‑fashioned, and younger generations preferred irony over innuendo.

Today, a saucy, seaside humor postcard is viewed with nostalgia. They are snapshots of a more innocent age, a reminder that cheap holidays consisted of fish‑and‑chips dinners and nights-out were spent in overcrowded boarding houses.

And believe me or not: shops in some seaside towns still sell such cards because they’ve become part of the national identity.