To young learners, those who think no one lived in North America before Christopher Columbus made his voyage of “discovery” in the late fifteenth century, I plead, “learn the facts that the Ocmulgee Mounds teach us.”

The presence of humans at Ocmulgee, near current day Macon, Georgia, began during the Paleo‑Indian period, when highly mobile hunters roamed the Macon Plateau in pursuit of life sustaining shelter, food, and security. Archaeological evidence, including distinctive hunting weapons, places early residents in the region at least 10,000 years ago.

Even that long ago, the climate changed and the people adapted to new environments, relying on hunting deer, fishing, and gathering nuts, berries, and roots. Their seasonal camps in places such as on the Macon Plateau changed from short-term (seasonal) to long-term relationships between humans and the landscape.

During the Woodland period, beginning around three thousand years ago, communities became more settled. They cultivated plants such as sunflowers and maize, then built semi‑permanent villages. This era also saw the development of early mound‑building traditions, though the monumental earthworks that define Ocmulgee today would emerge later.

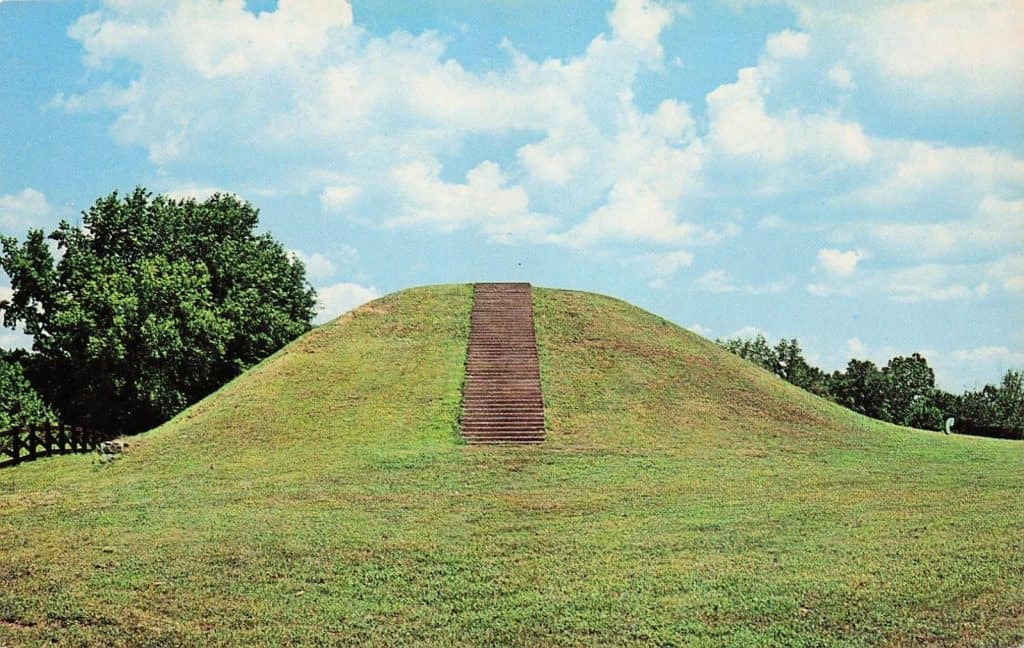

(This is probably a poor example to use as an introduction to mound building. There were no rail fences nor purpose-built stairways to the summit, and for certain the grass was not cut.)

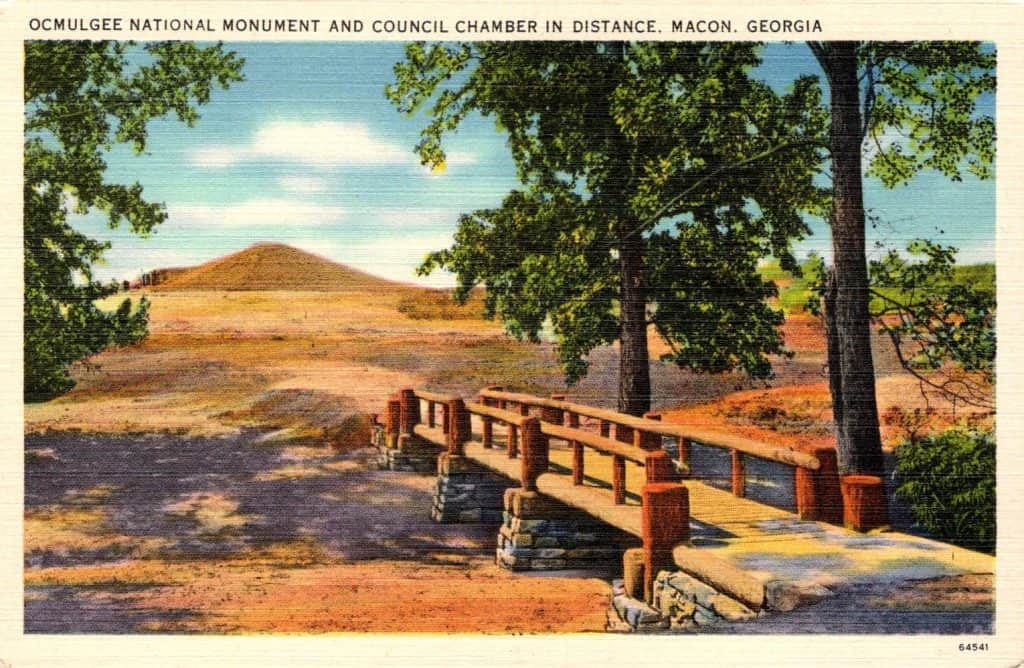

Around the year 900, history saw the dawn of a new cultural era, the Mississippian Period. The new era is historically characterized by the construction of large mounds and ceremonial earthworks, intended to document the existence of those with newly acquired ideas about politics, religion, and social function. Elevating the homes of leaders or creating schemes for important public buildings were also part of the evolution.

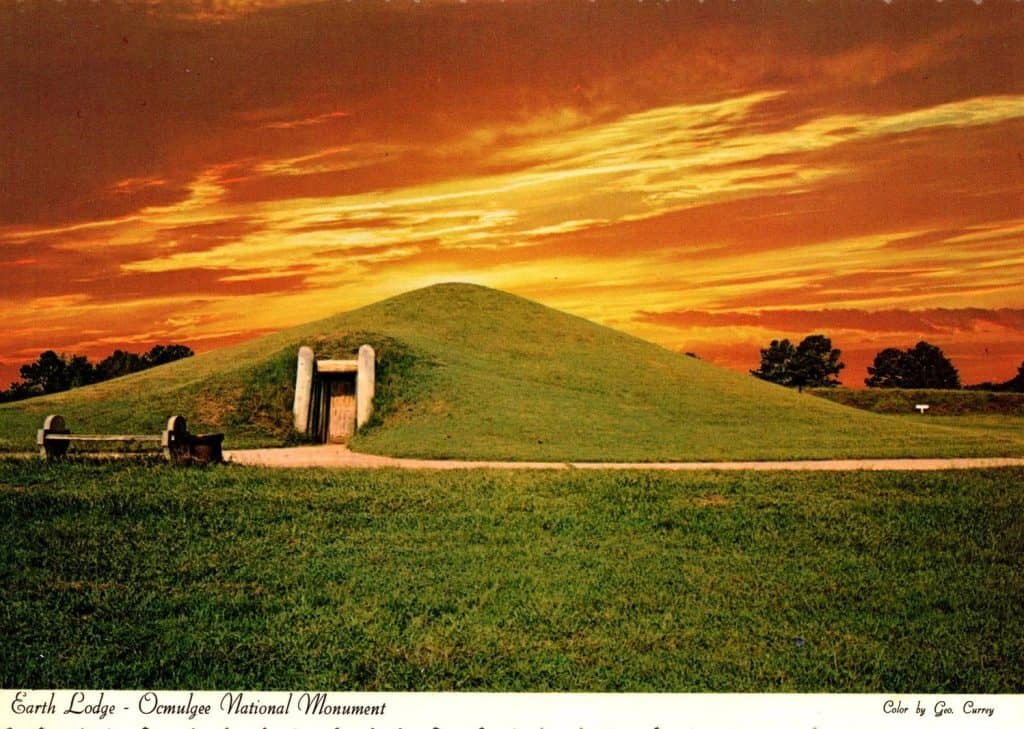

One of the most remarkable structures at the Ocmulgee site is the Earth Lodge, a ceremonial building with a clay floor shaped like a bird effigy that has been dated to around 1050. That floor is among the best-preserved examples of Mississippian architecture in North America and offers a vivid glimpse into the ceremonial life of the community.

The Mississippian settlement at Ocmulgee was only one part of a broader network of mound‑building societies across the Southeast, that were connected through trade, shared religious practices, and political alliances.

Ocmulgee is the ancestral homeland of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, whose cultural roots run deep in the region. When the Europeans arrived in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries they brought profound disruption to trade, caused dire conflict, and carried with them diseases that reshaped every Indigenous life. By the early eighteenth century, the Muscogee were navigating complex relationships with British traders, and the area around Ocmulgee became a site of colonial communication often without a scintilla of agreement.

The nineteenth century brought further upheaval. Through a series of land cessions and forced removals, the Muscogee were displaced from their homeland, culminating in their relocation to present‑day Oklahoma. Despite this, the Muscogee Nation maintains strong cultural and historical ties to Ocmulgee, and their involvement remains central to the site’s interpretation.

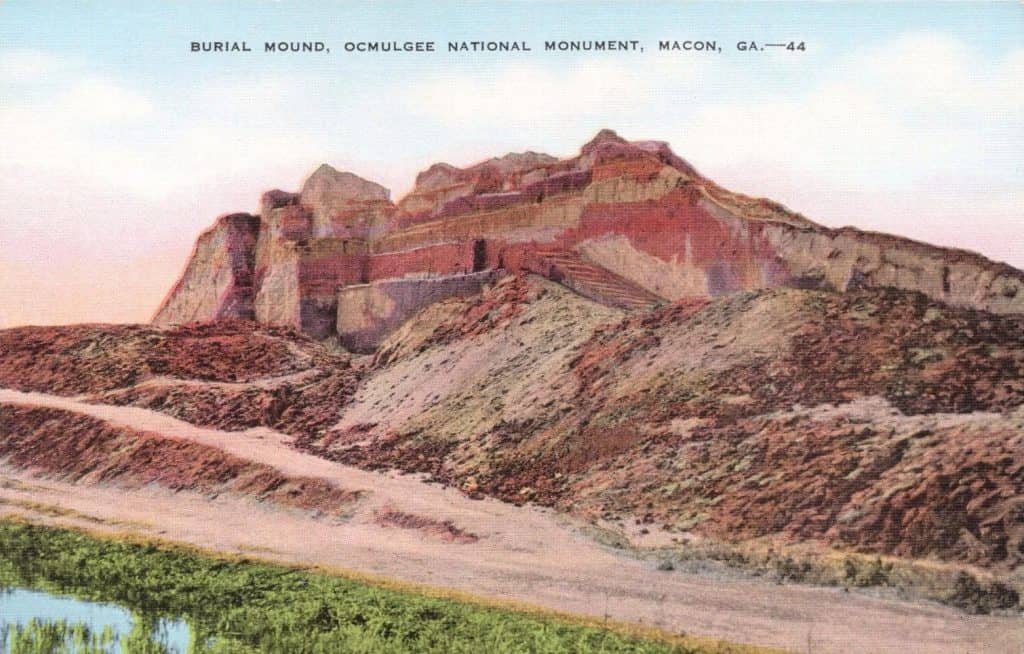

Archaeological interest in the Ocmulgee region began in the early twentieth century. During the 1930s, large‑scale excavations, many conducted by the Civilian Conservation Corps, uncovered more than one million artifacts, revealing the depth of the site’s history. These efforts laid the foundation for the establishment of Ocmulgee National Monument in 1936.

The National Park Service plays a crucial role in the ongoing preservation, interpretation, and public stewardship of the Ocmulgee Mounds. As caretakers of the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, the NPS protects the archaeological features, maintains the Earth Lodge, and manages the museum collections that hold thousands of artifacts.

Equally important, the park service collaborates with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation to ensure that interpretation reflects Indigenous perspectives and that educational programs like field trips, and events such as the annual Ocmulgee Indigenous Celebration help connect visitors with the living traditions of the Muscogee people.

The Ocmulgee Indigenous Celebration is an annual event usually held in September at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park in Macon, Georgia. It is a cultural gathering that serves as both a homecoming for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and a public celebration of Indigenous history, art, and living traditions. If you live in the area or can travel in September, don’t miss this event; it is a family‑friendly festival that highlights Indigenous culture, storytelling, and craftsmanship.

I attended the 33rd annual event in 2025. I hope to never miss another.

Thanks to the National Park Service’s stewardship, the heritage of Ocmulgee is protected and shared with visitors. It is one of America’s remarkable landscapes.

It is interesting to note that the earth to build the mounds was moved in baskets. These mounds can be found in many U.S. states.