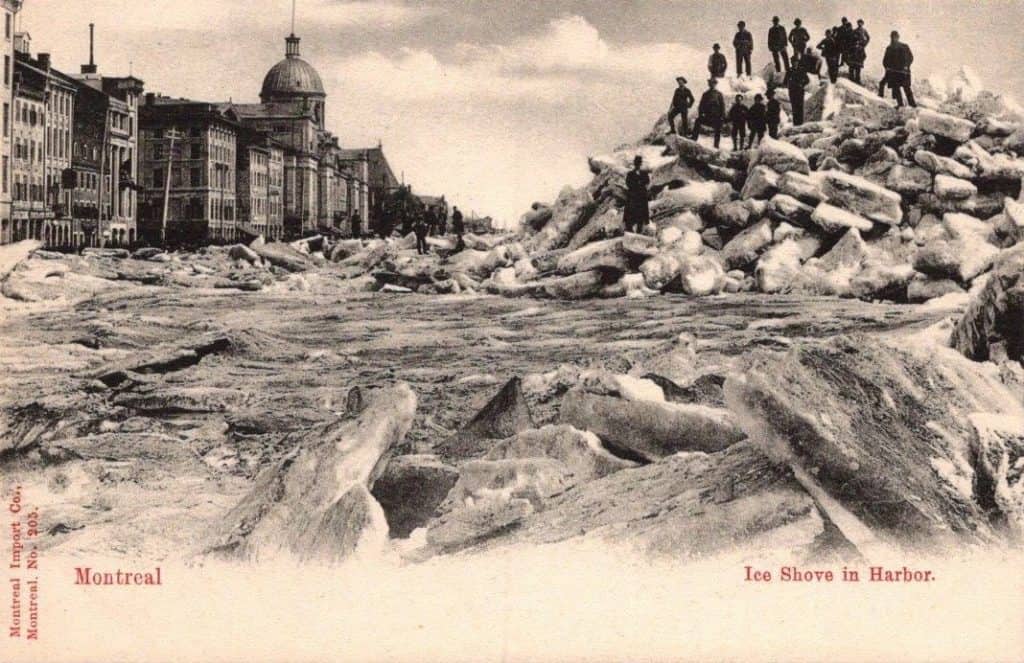

An Ice Shove? You may be unfamiliar with the term, but you will surely recognize what it is! Montreal, Quebec, circa 1910

An ice shove is an early spring event that is natural and attractive. There were times, mostly in the early twentieth century when people (families) would travel hundreds of miles to see one. A shove happens slowly but is also unstoppable. (Some attempts to stop a shove have resorted to the use of explosives and failed.). Ice shoves always occur in northern cities along large rivers or lakes that experience long periods of icy weather. It is a kind of frozen migration driven by wind, water, and temperature. At its core, an ice shove is a surge of lake or sea ice pushed onto the shore by strong winds, currents, or rapid temperature changes. These forces cause large sheets of ice to detach, drift, and eventually pile up on land, sometimes climbing over beaches, roads, and even into yards and buildings.

The North American city with the most notorious reputation for exploiting their Ice Shoves is Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Postcards are not abundant but there are some from the early decades of the twentieth century that will amaze and amuse.

It is difficult to identify the year of some Ice Shoves because the consequences of ice shoves are quite similar, but used cards with postal cancels help date some cards. The one above was mailed in 1910 and clearly shows the Cathedral of Saint Joseph’s Oratory of Mount Royal at the back, left-center. This places the image in the St. Lawerence River at or around the harbor area just north of Nuns’ Island and South of Ile Notre-Dame – about where the current day Samuel-de Champlain bridge on Autoroute 10 crosses the St. Lawrence River.

The phenomenon is often compared to a “slow‑motion ice tsunami,” not because it behaves like a breaking wave, but because of the sheer mass and momentum. When conditions align, loose ice and powerful winds, the ice can advance very quickly, scraping across the ground, gathering debris, and stacking into jagged ridges that may reach several stories high.

Ice shoves typically occur in late winter or early spring, when warmer temperatures weaken the ice cover. As the ice becomes more mobile, strong winds push it toward shore with enough force to damage structures, uproot vegetation, and reshape the immediate landscape. In some cases, homeowners have watched a “shove” of ice creep into their yards and press against their homes, causing broken windows or crushed siding.

Climate patterns also influence how often these events occur. As global temperatures rise, some regions experience more open water during winter, which can increase the mobility of ice sheets and make shoves more likely.

Despite their destructive potential, ice shoves are visually striking and although motion is slow, they are fun to watch and can with little notice become very dynamic.

An Avalanche, British Columbia, 1910

During the winter of 1909–1910 in the Canadian Southwest there were weeks when the weather conditions were particularly favorable to avalanches. Many slides occurred throughout January and on February 22nd a new round of storms hit Vancouver Island with a devastating punch. Over a nine-day period nearly 30 feet of snow hit the Roger’s Pass in British Columbia.

The Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental route through Roger’s Pass to Canada’s west coast was completed in November 1885 and was the only such link. It was necessary to keep it open throughout the winter months, but the route was often abandoned because the snow would bury the line and avalanches tore away newly laid sections of track that year after year needed rebuilding. The avalanches also routinely destroyed the system of “snow sheds” (nearly four miles long) that were constructed to protect the most vulnerable sections of track. Nevertheless, in 1910, most of the route through the pass was still unprotected, meaning that men and equipment were often called upon to clear the snow.

That was the case on March 4, 1910, after the nine-day storm of snow and wind finally subsided enough that rotary plows and men with shovels could go to work clearing the tracks through the pass. Then, that night, just before midnight they were hit by the largest snowslide in provincial history.

That March 4th work crew had been dispatched to clear a big slide which had fallen from Cheops Mountain and buried the tracks just south of Shed 17. The crew consisted of a locomotive-driven rotary snowplow and 63 men. Time was critical since the westbound Train Number 97 was just entering the mountains to the east and was bound for Vancouver.

(This RPPC image has been electronically enhanced for clarity.)

The front page of the Monday, March 7, 1910, issue of The Montreal Daily Star carried three photos of a “Fatal Snowslide at Roger’s Pass” in British Columbia. The story continued with a Page 15 headline reading, “Sixty-two Men Missing in Fearful Snowslide in the Rockies.” The report told that the most disastrous avalanche in the history of railroading in the mountains of British Columbia came down near Roger’s Pass, about two miles east of Glacier, shortly before midnight Friday. The snow slide travelled two miles before reaching the main track of the Canadian-Pacific Railroad where crews were working.

About half an hour before midnight when the track was nearly clear, an unexpected avalanche from Avalanche Mountain swept down the opposite side of the track to the first fall. Around 250 yards of track were buried. The 91-ton locomotive and plow were hurled from the tracks and landed upside down. The wooden cars behind the locomotive were crushed and all but one of the workmen were instantly buried in the deep snow. The only survivor was locomotive fireman Billy Lachance, who had been knocked over by the wind accompanying the fall but otherwise remained unscathed.

(This RPPC of the 1910 cleanup operation has been

electronically enhanced for color and clarity.)

This disaster was not the first to befall the pass; in all over 200 people had been killed by avalanches there since the line was opened 26 years previously. The CPR finally accepted defeat and in 1913 began boring the five mile long Connaught Tunnel through Mount Macdonald, which was then Canada’s longest tunnel. It opened on December 13, 1916.

The folks along Lake Erie will probably experience major “Ice Shoves” this year… the thaw is coming! I’ve seen simple snow plows on the train cars in Kansas, but the one from Canadian Pacific Railway is even more impressive. Thanks for this article.

Thank you very much for this article which is very interesting. Both my mother and myself have been over the Rogers Pass so reading it brought back happy memoies for me

Great research on an interesting topic. Ive been educated today, thanks.

What rugged men they were then.

Always enjoy reading your articles. This one is perfect for the winter of 2025-2026. Snow postcards are always dramatic.

This is great – it was certainly a coincidence that I had a postcard from the avalanche in my Wichita presentation last weekend! I should correct myself and note that Rogers Pass is in fact in the Selkirk Mountains, not the Rockies, which are to the east of the Selkirks. British Columbians always roll their eyes on hearing flatlanders refer to every mountain in B.C. as part of “the Rockies” when in fact that is only one of several large mountain ranges. The Montreal ice-shove cards are also nice ones – in Winnipeg (and other cities) there used to be… Read more »