Bill Burton

Charles Lindbergh, Aviator

Early in life Charles A. Lindbergh exhibited an interest in mechanical things, particularly automobiles. In 1920, aged 18, he enrolled in the University of Wisconsin as a mechanical engineering student but early in 1922, when the aviation craze caught up with him, he dropped out and began his love affair with the airplane.

Lindbergh’s first flight was as a passenger at a flying school in Lincoln, Nebraska, but he never soloed and soon got a job as a daredevil, a “wing walker” and a parachutist. He bounced from job to job for the rest of 1922, learning enough to get a solo license the next year and barnstormed across various southern and midwestern states learning night flying and twice taking a doctor across flooded areas in Wisconsin to provide emergency medical treatment.

In 1924 Lindbergh joined the U. S. Army Air Service for a year of official flying instruction and graduated first in his class in 1925 as a second lieutenant. However, the Army didn’t need active-duty pilots and he was placed in the reserves. Lindbergh returned to civilian life and became a pilot who surveyed airmail routes in the midwest, then got a job to fly these routes to and from various midwestern cities.

The flying craze that boomed through the 19-teens included challenges to cross the Atlantic. The first successful flight was made in 1919, but it was short, from St. Johns, Newfoundland, only to Ireland. A New York hotel entrepreneur, Raymond Orteig, then offered a $25,000 prize for a flight between New York and Paris (in either direction) if completed during the next five years. Despite the large prize, there were no takers.

In 1924, Orteig renewed the prize and while several experienced pilots sought the prize. None succeeded and several disappeared after departing on their flight.

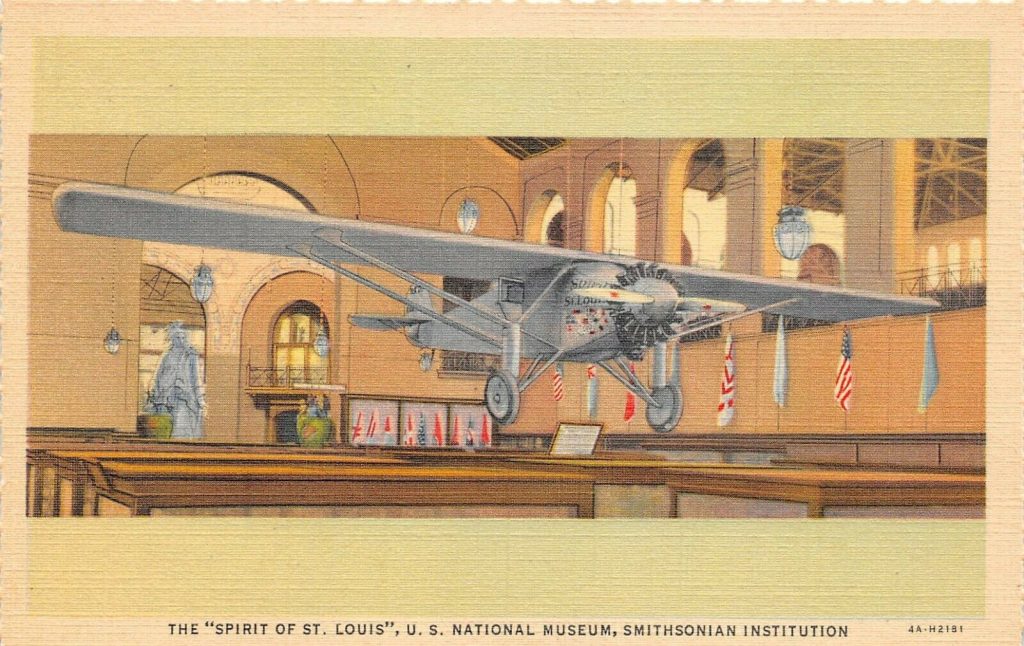

Lindbergh obtained some financing from two St. Louis businessmen, put in money from his savings as an airmail pilot, and found a California company that constructed a plane with a linen cloth skin and extra-large fuel tanks. He flew it from California to New York, refueled, and on the morning of May 27, 1927, headed northeast along the coast to Newfoundland and out to sea. 33½ hours after he left New York, he landed in the dark at Le Bourget Field outside Paris, where he was greeted with a rapturous reception.

Vaulted from his life as a daredevil aviator to vast international fame, Lindbergh was showered with honors. U. S. President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross (illegally, because it was reserved for feats during the flyer’s military service), the French government gave him the Légion d’honneur, and topping everything, the U. S. Congress presenting Lindbergh with the Congressional Medal of Honor, despite the fact that the medal was meant for service during wartime. That problem was considered a minor detail.

In June 1927 the U. S. Post Office issued a 10¢ air mail stamp in his honor. And Orteig paid the prize money.

Barely two months after his landing in Paris, Lindbergh’s autobiography, WE, was published by G. P. Putnam. Its sales earned ten times the Orteig prize. He began touring not just the U. S. in his plane but also various South American countries. Everywhere he went he was greeted with parades and dinners. In Mexico he met Anne Morrow, the daughter of the U. S. ambassador there, and they married in 1929.

Anne’s father, Dwight Morrow, was a partner with J. P. Morgan and advised Lindbergh on financial matters. The couple first lived at his estate in Englewood, New Jersey before buying their own home in East Amwell (near Hopewell), New Jersey. Not surprisingly, Lindbergh had been flooded with business opportunities and he spent a great deal of time away from home attending various aviation-related projects.

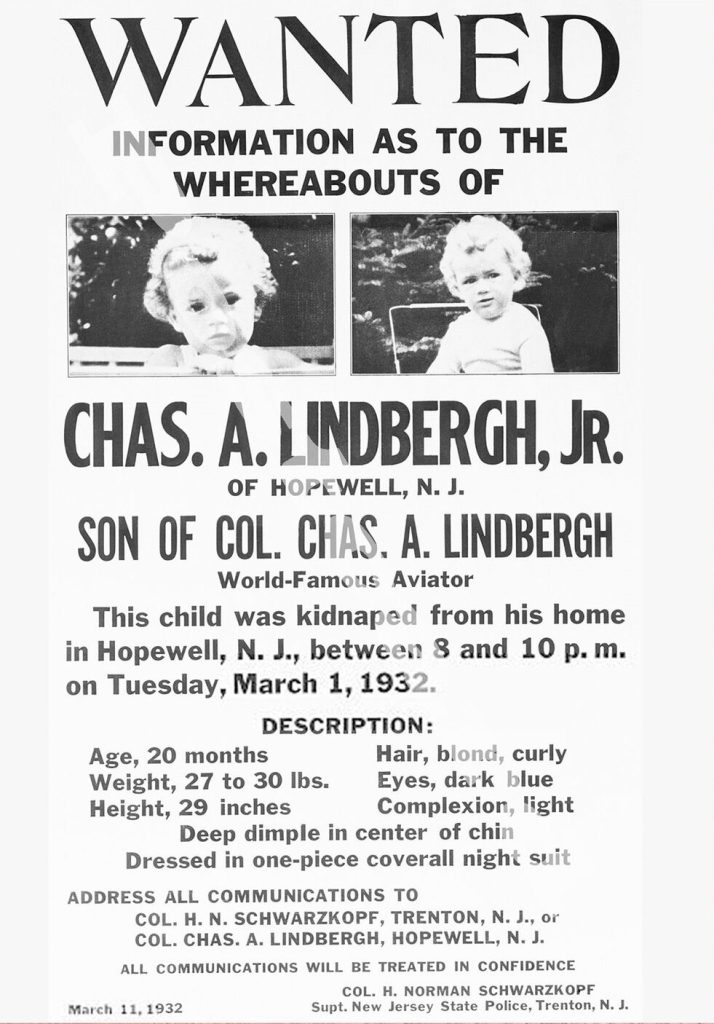

The Lindbergh’s first child, Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. was born in 1930. The 20-month-old toddler was kidnapped from his bedroom on March 1, 1932, and vast international attention was again focused on Lindbergh. Journalist H. L. Mencken called the kidnapping “the biggest story since the Resurrection.” The kidnapper, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, was not arrested until September 1934 but was quickly convicted of kidnapping and murder in February 1935. After he had exhausted his appeals, Hauptmann was executed in April 1936.

The Lindberghs fled the attention of the trial and in December 1935 with their second child Jon, left the U. S., fleeing first for England and then to France. They did not return until 1939 when Lindbergh (by then having been promoted to colonel) was recalled by the Army Air Corps to review preparations for the coming war, and he toured American air bases and other facilities and wrote a substantial report for the Army on the level of air preparedness.

In the four years Lindbergh was in Europe, he travelled extensively, frequently to Nazi Germany. He was fêted and shown its burgeoning air power, which he publicly described in glowing terms. Those and other remarks he made evoked considerable controversy and insinuation at home about his support of the Nazis and his assertion that “Europe and the entire world is fortunate that a Nazi Germany lies, at present, between Communist Russia and a demoralized France.”

These and other remarks led many to say he was a German sympathizer. When he returned to the U. S. in 1939, he like his father, a Minnesota Congressman from 1907 to 1917, took an isolationist position. Lindbergh saw the war in Europe as a fratricidal conflict among various European states, one which America should avoid entering.

He expanded his position that America needed to avoid the war in a speech in November 1939 and an article in Reader’s Digest titled “Aviation, Geography, and Race,” where he praised the existence of American aviation as “one of those priceless possessions which permit the white race to live at all in a pressing sea of yellow, black, and brown.”

Lindbergh joined the America First Committee and began barnstorming the country to avoid involvement in the conflict.

In a speech titled “Speech on Neutrality” in Des Moines, Iowa on September 1, 1941, he went further. “The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish, and the Roosevelt administration. Behind these groups, but of lesser importance, are a number of capitalists, Anglophiles, and intellectuals who believe that the future of mankind depends upon the domination of the British empire. Add to these the Communist groups who were opposed to intervention until a few weeks ago, and I believe I have named the major war agitators in this country.”

Early in 1942, when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent declaration of war by Congress had occurred, Lindbergh (who had resigned his commission in 1939) applied for reinstatement in the Army Air Corps. His request was denied, and he was enlisted as a consultant by several aircraft manufacturers and eventually flew their products in as many as 50 missions against the Japanese.

In 1954, President Eisenhower restored Lindbergh’s Air Force commission and promoted him to brigadier general in the Air Force Reserves. In his later years, Lindbergh drifted away from his marriage and family, fathering children with three different women in Germany. He became passionate about environmental causes and moved to Hawaii, where he died and is buried.

I noted from the poster related to the kidnapping that correspondence could be addressed to H. Norman Schwarzkopf, whose namesake son was commander of U.S. Central Command during the Gulf War.

Another excellent article from Bill. For those who want to learn more about Lindbergh and his competitors who wanted to be first to fly from New York to Paris, I highly recommend Joe Jackson’s book Atlantic Fever. Lindbergh succeeded when several other pilots failed. Some lost their lives, making Lindberg’s flight heroic.

As great a air pilot as Charles Lindbergh was and as much notoriety he made for himself and our country he lost a lot of his glitter as World War II began. His actions and speeches, at this time, tarnished a truly great accomplishment.

It’s obvious that Lindbergh, like most of our species, had some flaws. In this case, rather serious flaws.