“Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

The phrase above is a common one attributed to Sir Anthony Weldon (1583–1648), a 17th-century courtier and English politician. Fundamentally it means that it’s not your fault if you’re tricked by someone, but if you trust them and they trick you again, then you have to accept that you should have known better and learned from the first event.

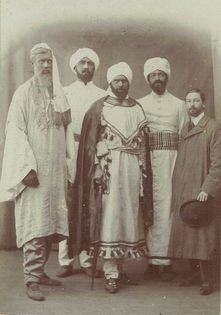

The phrase fits well concerning two incidents which occurred in the first decade of the last century. The first event was the topic of a card found a few years ago that was titled The Cambridge Hoax. Then the card above, Distinguished Visitors!” March 2nd, ‘05, was found and serves as a reminder of the first and is likely associated.

Sadly, this card contains no publisher’s details, but I have seen the same card with the words The Cambridge Hoax placed above the turbaned gentlemen that was the product of the Cambridge Picture Post Card Company. The Cambridge card was postmarked in Cambridge on March 29, 1905, so it is contemporary with the event.

The illustrator, Frank Keene, has added his initials ‘FK’ to the image. There are other cards so initialed, but I have never found biographical information regarding Mr. Keene. [Aside: the 1911 census has only one Frank Keene who records his profession as artist. That individual was Frank Drysdale Keene who was born in Bedford circa 1883, and was the son of a better known artist named Ezra Elmer Keene. Ezra’s work is frequently found on the Chic Series postcards published by Charles Worcester and Company.]

To the story: Ali bin Hamud al-Busaidi (1884 –1918), also known as Ali II, was proclaimed Sultan of Zanzibar on July 20, 1902, two days following the death of his father. In 1905 he arrived in Great Britain on a state visit. A quote from the Western Gazette of March 10, 1905, takes up the story ….

A MAYOR HOAXED

CAMBRIDGE UNDERGRADUATES’ DARING TRICK

The Mayor of Cambridge has been the victim of one of the most audacious and carefully planned practical jokes ever perpetrated by undergraduates. His Worship received a telegram on Thursday stating that the Sultan of Zanzibar, who is on a visit to this country, would arrive at Cambridge for a short visit, and could he arrange to show him buildings of interest and send a carriage? The telegram was signed Henry Lucas, Hotel Cecil, London.

On receipt of the telegram the Mayor and the Town Clerk, an old Emmanuel College man, determined to do the honors of the town for their distinguished guests as well as was possible at such short notice. Later in the afternoon, four gentlemen arrived by train. They had dark complexions and were dressed in gorgeous flowing garments and brilliant turbans on their heads. They were accompanied by a gentleman in ordinary clothes, their interpreter, one Mr. Harry Lucas. The four dark gentlemen were “Prince Mukasa Ali” and three members of his suite.

The party on arriving in due course drove to the guildhall, where they were received by the mayor wearing his chain of office and the town clerk.

Here was explained that the Sultan himself was unfortunately unable to come, and so his place had been taken at the last minute by his uncle, Prince Mukasa Ali. Meantime news of a distinguished stranger’s arrival had got about, and as the party came down the steps from the guildhall to enter the carriage a large crowd cheered heartily, the prince gracefully acknowledging the salutation, and even distributed some largesse. The visitors, indeed, except upon one occasion, spoke very little, but salaamed continually, and addressed each other by signs on their hands. The party visited the “fellows’ gardens” and “the backs.” But Prince Mukasa complained of the cold, so they returned and visited St. John’s College.

Time, however, was now short, and after a walk-up Trinity Street, the Prince and his suite took leave of their kind hosts and drove off to the station, having-first expressed their deepest gratitude for the reception accorded to them.

Subsequently the Prince and his suite went to a pre-arranged spot, and doffing their gorgeous robes, made their way back to their rooms.

The next day certain members of the party again proceeded to London and returned to a well-known costumier the garments which they had hired for the occasion. Enquiries at the Carlton Hotel showed that the Sultan himself was attending Buckingham Palace on Thursday, when he had an audience of His Majesty by one of his attendants, the Sheikh, while his secretary remained in the hotel. The members of the suite were also in the hotel during the time they were supposed to be at Cambridge.”

The “Prince” was William Horace de Vere Cole (1881-1936) whom Wikipedia describes as “an eccentric prankster” born in Ballincollig, County Cork, Ireland. He was accompanied by other students including Adrian Stephen (brother of Virginia Woolf). The prank completely fooled the Mayor of Cambridge, and would likely not been discovered except that two days later Cole confessed all to the newspapers.

The following is from the Eastern Evening News of March 8, 1905.

STORY OF THE CAMBRIDGE HOAX.

INTERVIEW WITH “THE PRINCE.”

An amusing description of his experience has been given by the Cambridge undergraduates who posed as uncle of the Sultan of Zanzibar, and who hoaxed the Mayor and Town Clerk of Cambridge, by whom he was officially received and conducted over the city. The pseudo-African prince has been at great pains to conceal his identity, but after three days’ search, he was discovered in the university by a Daily Chronicle representative.

After relating how he and his three companions (who acted as his suite) obtained their gorgeous robes from a London costumier and darkened their complexions, the Prince said that never once were their bona-fides doubted. They were treated with extreme politeness by everyone with whom they came into contact.

At Liverpool Street Railway Station, the departure of the party caused much excitement. On the way to Cambridge fears were expressed that they had been overheard to speak in English, but the indiscretion apparently passed unnoticed.

Describing the official reception at the Cambridge guildhall, the Prince laughingly remarked that he had only to grunt, and the Mayor and Town Clerk bared their heads and extended a welcome. The instruction given to the cabmen by the agent for the party to drive to the railway station after the entertainment was to throw the authorities off the scent. As a matter of fact, the vehicles went in another direction, and the practical jokers got back to their college undetected.

The ringleader ridiculed the statement by the mayor that he had not spent a penny on his dusky guests, and a guidebook and the mayor’s card were produced as spoils.

Another relic of the famous hoax is a photograph of the four daring undergraduates in their oriental robes. Although all four are well-known men in the college, it is impossible to identify them in the photograph, so perfect is their makeup.

By way of bravado the undergraduate mentioned that the prince was 6 feet high, and his companions 6 feet 4 inches, 6 feet 2 inches, and 6 feet 5 inches, respectively. There is little likelihood, however, of the university authorities attempting to follow up the slender clue by ordering a general measurement of the undergraduates.

“There are four suspicious bed makers in this college,” added the prince, in taking leave of his interviewer, “but we have little to fear at detection. I might perhaps also mention that in order to make sure that the hoax should reach the public ear we visited a London journal. Even the editor of that paper did not at first believe the story of the hoax and sent a reporter to Cambridge to make inquiries.”

Returning to the card, the illustration shows the Prince and his suite meeting with the Mayor and Town Clerk with the mayor wearing his regalia of office and the clerk carrying a guidebook of the city.

This essay opened with a phrase which included “fool me twice, shame on me.” Well, in truth, the Mayor of Cambridge wasn’t fooled twice although in 1910 Horace de Vere Cole pulled a further stunt which was even more audacious. This hoax is known as The Dreadnought Hoax.

Wikipedia tells us that this involved Cole and five friends – writer Virginia Stephen (later Virginia Woolf), her brother Adrian Stephen, Guy Ridley, Anthony Buxton, and artist Duncan Grant — who had themselves disguised by the theatrical costumier Willy Clarkson with skin darkeners and turbans to resemble members of the Abyssinian royal family. The main limitation of the disguises was that the “royals” could not eat anything, or their makeup would be ruined. Adrian Stephen took the role of interpreter.

On February 7, 1910, Clarkson’s employees visited Woolf’s home and applied the stage makeup to Woolf, Grant, Buxton, and Ridley, then provided eastern robes.

A friend of Stephen’s sent a telegram to the “C-in-C, Home Fleet” (Commander-in-chief of the vessels defending Britain) stating that Prince Makalen of Abbysinia [sic] and suite would arrive at 4:20 today in Weymouth. He wishes to see Dreadnought. Kindly arrange to meet them on arrival.” The message was signed “Harding Foreign Office”.

Cole had found a post office staffed only by women, as he thought they were less likely to ask questions about the message. Cole, with his entourage, went to London’s Paddington station where Cole claimed that he was “Herbert Cholmondeley” of the Foreign Office and demanded a special train to Weymouth. The stationmaster arranged a VIP coach.

In Weymouth, the navy welcomed the princes with an honor guard. An Abyssinian flag was not found, so the navy proceeded to use that of Zanzibar and to play Zanzibar’s national anthem.

The group inspected the fleet.

To show their appreciation, they communicated in a gibberish of words drawn from Latin and Greek; they asked for prayer mats and attempted to bestow fake military honors on some of the officers.”

The Cambridge hoax was a remarkable piece of fun although the Dreadnought Hoax would have been the equivalent of a modern day guided tour of a nuclear missile base given to a class of university students. The Dreadnought was the most powerful weapon of the time although – per the following from the Evening Irish Times of February 14, 1910 – these students had “Access All Areas” type passes.

“With characteristic hospitality the officers of the battleship strove their utmost to shower honors and attentions on their guests. The attaché from the Foreign Office was charming, and his explanations were complete. He told what pleasure it would give the Princes to see over the warship and informed one of the officers that the Princes were on a visit to this country in order to make arrangements for sending their sons and nephews to school at Eton.

So, the Princes were shown everything — the wireless, the guns, and the torpedoes, and at every fresh sight they murmured in chorus, “Bunga, bunga” that was interpreted as, “Isn’t it lovely.”

Delightful article. Horace deVere Cole becomes fairly famous for his ‘tricks.’ thanks for these two.

I wouldn’t be at all surprised if The Cambridge Hoax could still be carried off fairly easily today with only minor tweaks. Maybe it has! Maybe we haven’t gotten a postcard for “The Harvard Hoax” because the students pulled it successfully but never confessed.

Interesting that, after Cole and his “Merry Pranksters” pretended in 1905 to be from Zanzibar, the Zanzibari anthem was played for them as “Abyssinians” five years later!