There are several analytical studies that have examined the psychological condition known as Schizoid Personality Disorder. Most people who choose to live as hermits are perfect examples. The individuals who suffer SPD are not immune from having their persona appear on postcards. The cards below portray three world famous hermits: an Englishman, an American, and a Frenchman who “soldiered” in North Africa.

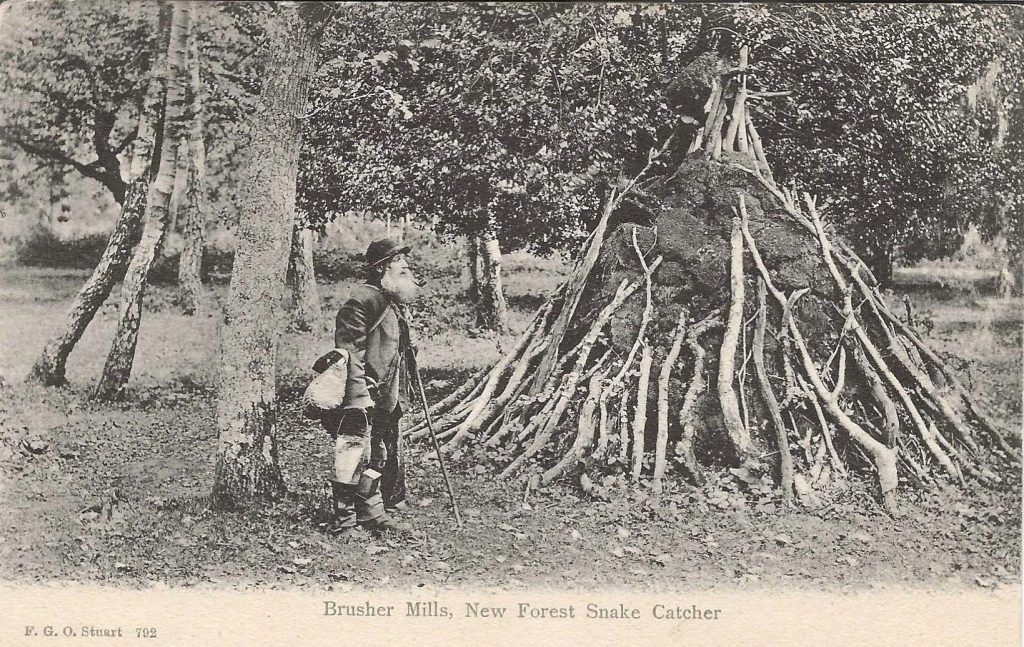

The Englishman, Harry “Brusher” Mills

When Brusher Mills died in early July 1905, another man of equal character with just as much charisma, inherited Harry’s shack that was made of tree limbs, twigs, sticks, and weeds. Also his other belongings – a forked snake-stick, and his snake-sacks. Yes, Harry was a hermit, but he had a job and by all accounts, he did it well. He was a resident “snake catcher” at New Forest.

Henry Mills was born in 1840 in the small Hampshire (England) village of Emery Down. His parents were not celebrities. His father, Thomas was a farm hand who worked for pence-per-day at growing, cutting, baling, and selling hay for the locals who owned horses.

It seems that in Harry’s early years he did nothing noteworthy. There are no civil, secular, or sacred records that carry his name as either Henry or Harry Mills. (There were others of the same name, but none born in 1840.) The first time he is mentioned in a public document is circa 1880 – at about age 40. Around that time, he decided to become a snake-catcher. He assumed possession of an abandoned property that once belonged to a charcoal maker. Henry’s new hut was deep in a woodland about a mile above Brockenhurst (a village just eight miles southwest of Southampton, England.) His way of life made him a local celebrity and an attraction for visitors to the New Forest.

Armed with cloth sacks and a forked stick, Harry would venture into fen or field to make a catch. He would “milk the snakes of their venom” to manufacture ointments for various maladies. He also boiled off the hides of snakes so that he could sell their skeletons to curious tourists. He supplied different species of snakes to the London Zoo as food for their birds as well as reptilian exhibits.

Harry Mills soon became a local curiosity, and a press article appeared on November 3, 1899, in the Westminster Budget that guaranteed national celebrity.

Harry had but one social interest; he loved cricket and seldom missed games played at Balmer Lawn. It was there that he was paid to maintain the “pitch” (an area of the field between the wickets) between innings. His work at the cricket games is what earned him the nickname, “Brusher.”

Harry Mills had but one “brush” with the law. His case was resolved but not in his favor. He soon afterward took up residence in an outbuilding of a local inn. He died there at age 65.

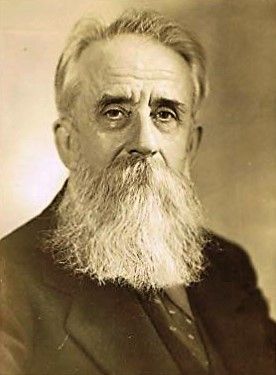

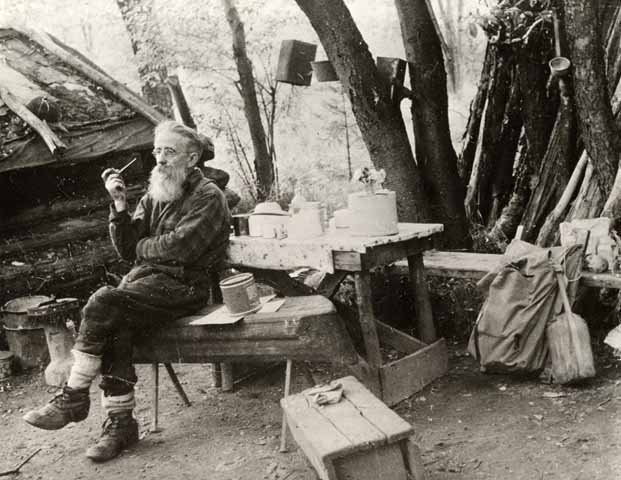

The American, Noah John Rondeau

It is seldom that a widely known hermit earns himself a New York Times obituary, but that was the case in the late summer of 1967. The headline read: The Hermit of the Adirondacks, Noah John Rondeau, Dead at 84.

Today and for the last half-century, the population of Au Sable Forks, New York, has dropped lower and lower. In 1883 when Noah John Rondeau was born there, it would be safe to assume that less than a hundred souls lived within walking distance of the Rondeau farm. The family patriarch was Peter, a French Canadian who ardently favored freedom from government and discouraged intrusion by neighbors. When Peter moved to Au Sable Forks, he brought along his wife Alice Corrow and their nine children.

Noah’s mother died when he was thirteen. He cared little about his siblings and ran away from home to find a safe shelter in the Adirondacks – primarily in Clinton County, New York.

Since his departure from home ruined his opportunity for an education, Rondeau finished only eight grades, yet was quite well read. He had a keen interest in science and astronomy.

Much of what he earned in his early years came from working in and around small New York villages such as Coreys in Franklin County, as a handyman and a guide along the Raquette River. For fifteen years his only real acquaintances were other hermit-like men, and his only real friend was Daniel Emmett, a Native American from Canada.

Other social interactions Noah had were his occasional visits to jail for game law violations.

Around 1929, then in his mid-forties, Rondeau began living alone in several remote areas, saying he was “not well satisfied with the world and its trends.”

During this period, Rondeau kept extensive journals, many of which were written in ciphers of his own invention. His efforts progressed through at least three revisions in the late thirties and early forties, and in their final form they resisted all efforts to be deciphered until 1992 when Life With Noah, was published.

Noah and most of his world regarded him as an Adirondack hermit, but he did accept visitors to his hermitage and even performed for them on his violin. He stood only 5′ 2″ but was skilled in many ways. He built himself two cabins and several wigwams, which later provided firewood. He lived primarily on trout, local game, and greens. His final cabin has been preserved at the Adirondack Experience, a museum near Blue Mountain Lake, New York.

Noah was a lovable character who was known to have said, “Man is forever a stranger and alone.” His most famous remark came in response to a question about crowds, “I don’t mind crowds as long as I’m going the other way.”

In 1950, New York State closed the forest area that Noah called “home.” It was soon after a destructive storm leveled the forest and rerouted the river. The closure forced Noah to move after 40 years in that Cold River woodland. At age 67, he moved to “convenient sites” around Lake Placid, Saranac Lake, and Wilmington, New York, until his death in 1967. He is buried in North Elba Cemetery in Lake Placid.

One very strange anomaly is that Noah worked at the North Pole Amusement Center as a substitute Santa Claus. After his move to Lake Placid, Noah never returned to the hermit lifestyle and eventually decided to accept the public welfare checks he had been offered for years.

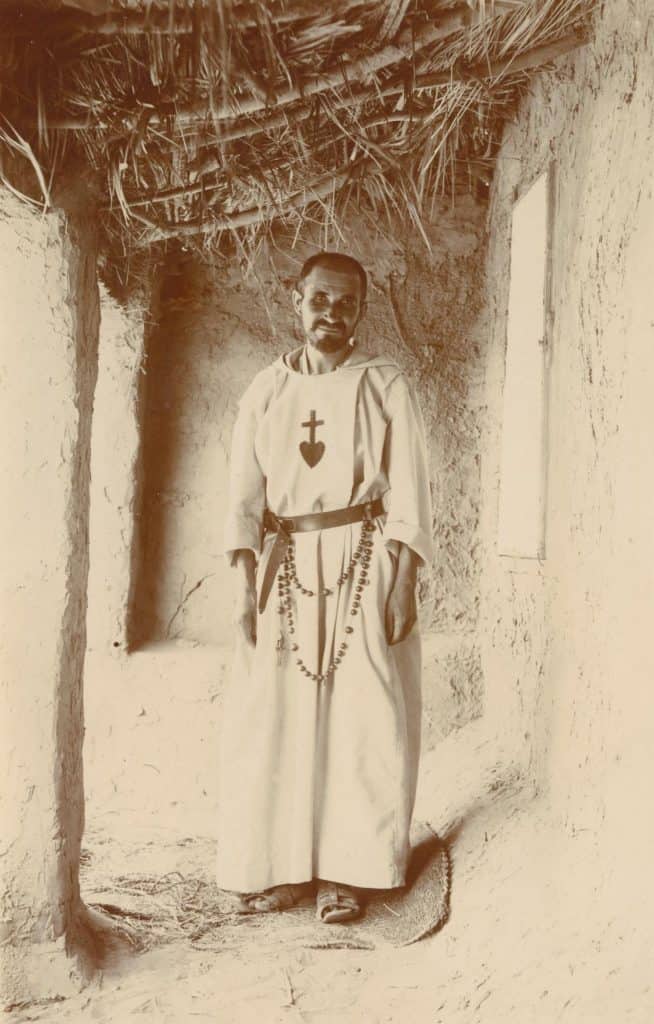

The French Soldier in North Africa

Charles Eugène, vicomte de Foucauld joined the human race at Strasbourg, France in 1858. Diaries kept by his parents clearly described events in Charles’s life as a victim of Schizoid Personality Disorder – long before a clinical diagnosis was formulated.

Charles’s father encouraged his son to study military science. Charles did so but quite reluctantly. Surprising as it was to the family, Charles enjoyed great success as a French soldier and explorer.

Foucauld first visited North Africa in 1881 as an army officer participating in the suppression of an Algerian insurrection. He led an important exploration of Morocco in 1883 that took more than a year. At a later time, he studied the oases of southern Algeria. His research data remained pertinent and were used by both Axis and Allied forces as late as 1943.

In 1890 he became a Trappist monk but soon left that order to become a solitary penitent in Palestine. In 1901 he became a missionary priest, establishing himself initially in southern Algeria and then at Tamanrasset in the Hoggar Mountains of the Sahara. He was one of the first Frenchmen to enter the area after its conquest.

Foucauld had a frugal nature and grew to be better known for his lifestyle and clerical writings that included life pattern lessons in the form of prayers and meditations. He singularly encouraged what he called, “a life – alone with God.”

Foucauld built a rough stone hermitage for himself on a mountain top and lived among the natives, whom he encouraged to be loyal to the French government. He further complimented the indigenous people as he compiled a dictionary of their language.

In 1916 Foucauld was killed by local rebels during an uprising against France.

In May 2022, Charles Eugene De Foucauld was canonized by Pope Francis. His “Saint’s Day” in the Catholic calendar is December 1st.

We had our own postcard hermit here: Adirondack French Louie.

Foucauld was honored on stamps issued by Algeria (1950) and France (1959).