HUGE CROWDS POUR INTO PHOENIX TO SEE THE MAN-BIRDS FLY,” blared headlines in the February 10, 1910, edition of the Phoenix Gazette. The occasion was the country’s second aero meet. In Part I, published here on postcardhistory.net on Tuesday, September 10th you read of the preparation and excitement that this event generated. Today the conclusion follows:

There were many prominent aviators to ensure large crowds. Charles Hamilton had flown at the Los Angeles meet and had already made several exhibition flights in California since the January meet. A student of Curtiss, Hamilton had contracted with the Curtiss Exhibition Company to fly the record-holding eightcylinder plane from the Rheims meet. Hamilton had recently trimmed six seconds from Curtiss’s world record for flying the one-mile oval, with a new time of one minute and twelve seconds – at speed of over fifty miles per hour.11 An avid self-promoter, Hamilton corresponded from California with Arizona newspapers to build interest in his appearance at the Phoenix meet.

Charles Willard, also a protege of Curtiss and an exhibition licensee, had flown with Hamilton as part of the Curtiss team at the Los Angeles meet. His plane, the four-cylinder, twenty-five horsepower “Golden Flyer,” was the first aircraft designed and built by Curtiss. Originally manufactured for the Aeronautical Society of New York, Curtiss had flown the plane to victory in the 1909 Scientific American Trophy race.12

Although less famous than Curtiss, Willard and Hamilton had quickly become prominent aviators. The Phoenix Gazette portrayed Curtiss as a “careful experimenter and manufacturer with a half-million-dollar plant who takes no unusual risks.” Hamilton and Willard, on the other hand, were described as “showmen and daredevils ready to thrill the crowd.”13

Three Curtiss planes arrived in Phoenix by rail on February 9th and were transported to the fairgrounds, where “mechanicians” worked all night uncrating and reassembling the machines. Charles Willard supervised the operation.

The Aero Meet program consisted of sixteen standard events. These included endurance tests; competitions for greatest altitude; high glide; a race with Mel Johnson’s chauffeur driven Buick, the “White Streak”; cross-country flights; quick starts; a slow mile; take-off and landing within a twenty-foot square; and passenger flight. In keeping with the style of the time, the meet featured a staff roster of prominent Phoenicians as judges, timekeepers, and starters. 14

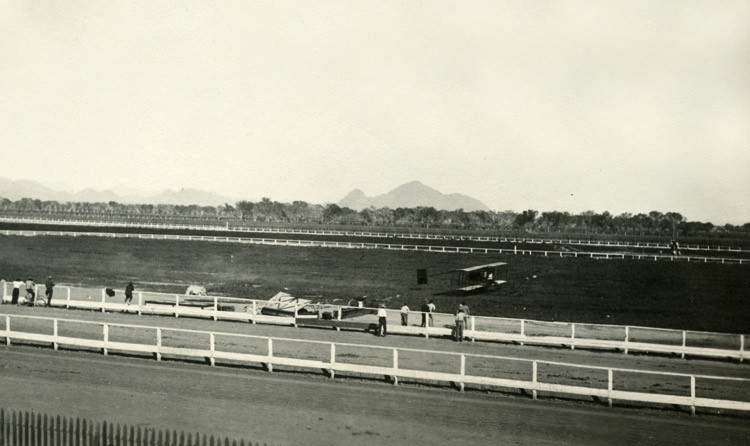

The Phoenix Aero Meet officially opened on Thursday afternoon, February 10, as Charles Hamilton soared above a crowd of 3,000 spectators. Starting from the three-quarter pole, Hamilton’s aeroplane climbed to a height of 200 feet. Willard, however, had trouble taking off and was forced to land in the nearby Latham Addition Subdivision for brief repairs. The crowd lost sight of the aviator and was greatly relieved when his plane returned to the fairgrounds about forty-five minutes later.

Other opening-day events included Willard’s two-mile cross-country flight, and Hamilton’s three-quarter-mile test flight, five- and six-mile cross-country flights, 200- and 300-foot-high glides, a short flight with passenger H. I. Latham, and a record-setting flight around a one-mile circular track.15

On February 11, the second day of the meet, spectators jammed streetcars and roads leading from the center of town to the fairgrounds. More than 7,000 people watched as Hamilton’s plane beat Mel Johnson’s Buick in a ten-mile race around Phoenix’s one-mile oval track. The winning time was 13:31.6. Willard further excited the crowd when his engine died in midflight and his plane crashed, breaking several wing ribs. Luckily, the aviator was not injured and, after quick repairs to the plane, he returned to the air.

In promoting the Phoenix Aero Meet, the Gazette boasted that the city’s climate and terrain were ideal for flight. “Few places are better provided with facilities for these contests,” the newspaper observed. “The racetrack has the world’s record for speed, and the field is practically clear of obstructions: there are no trees, [and] … the atmospheric conditions are dependable…. That is one of the assets of this valley, as aviators have learned and demonstrated.”16

The weather was indeed ideal, prompting additional flights on Saturday. Hamilton squared off against a Studebaker automobile in a five-mile competition and won once again. The April issue of Popular Mechanics touted the race as “the first speed contest of this kind to take place in this country.”17

Excitement mounted that afternoon as typical early-aviation accidents delayed two of Hamilton’s flights. In the first mishap, the propeller splintered, barely missing the ground crew, and embedding a two- or three-foot-long, inch-thick piece of wood in one of the plane’s tires. The crew replaced the propeller and tire in just a few minutes, and Hamilton took to the air.

In the second incident, the plane’s gas tank caught fire, burning over forty square feet of canvas before the pilot and the mechanic were able to extinguish the flames.

Hamilton raced against the Studebaker again on Sunday; this time, the automobile beat the aero plane by half a length. In another challenge, Hamilton pitted his aircraft against a Curtiss motorcycle over a five-mile course. This time the aviator easily outpaced his ground competition, which was running poorly. The following day’s newspaper headlines read: “Biplane puts Curtiss’ earlier invention out of the running.”18

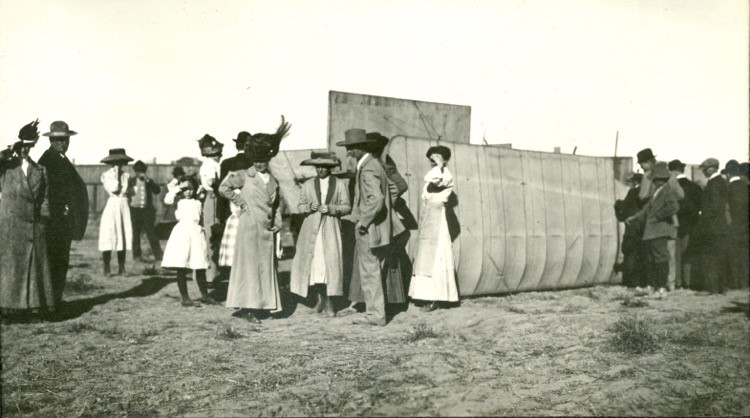

In addition to wire photos distributed to the press, photographs of the aeroplanes, personalities, and flights were in great demand among spectators. Along with George Sadler, the selfproclaimed official photographer, “Bob” Trumbull, unidentified photographers Harrigan and Christie, and most other amateur and professional photographers in attendance produced and sold photographs and postcards of the event. Photographic postcards were advertised widely and formed an important component of the aggressive promotion of Phoenix and its Aero Meet.

Several of the images used by the Republic and the Gazette also appeared as postcards. The Adams Pharmacy advertised six different one-cent postcards of planes and aviators, as well as some comic aviation scenes. At least one photographer offered portraits taken in front of the painted background of a plane in flight over Phoenix. Postmarks indicate that the cards were in circulation long after the meet.

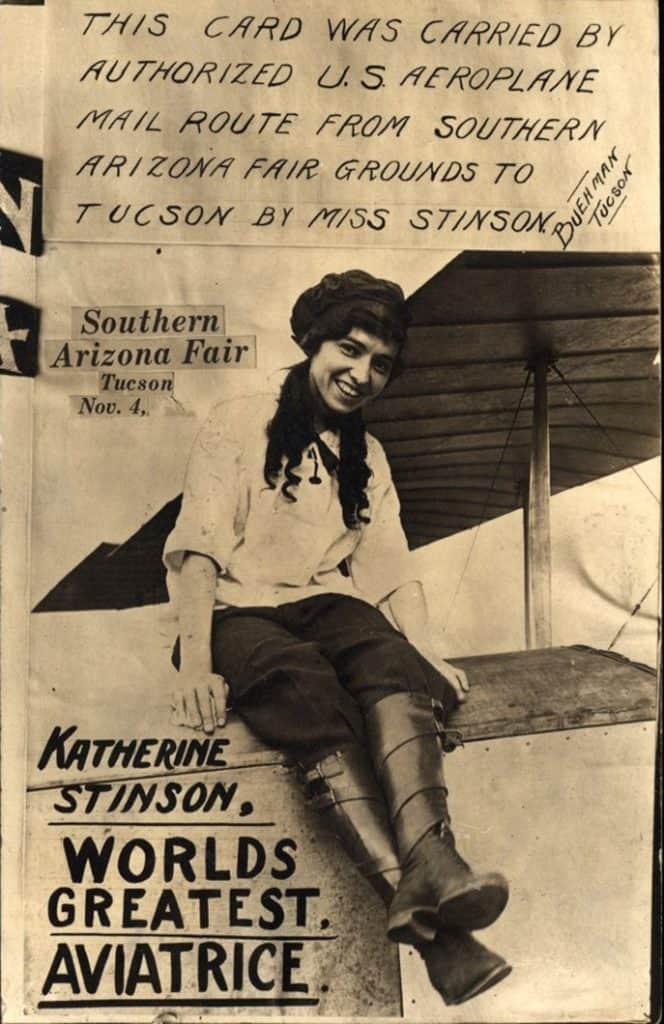

The 1910 Phoenix Aero Meet introduced aviation to territorial Arizona. From Phoenix, Charles Hamilton took his plane to Tucson, where he flew in exhibitions at Elysian Grove on February 19th and 20th. In his wake, Arizona became a haven for cross-country fliers.

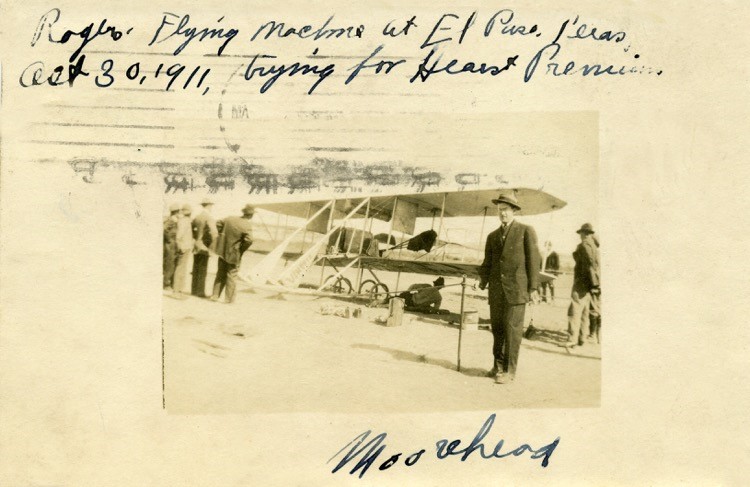

Cal Rodgers and the famous “Vin Fizz” crossed Arizona en route to California during his ill-fated cross-country attempt to win the prize offered by William Randolph Hearst.

In more perilous times Arizonans witnessed early experiments in airmail delivery, in aerial bombing during the Mexican Revolution, and the establishment of flight schools for military aviators during World War II.

Unfortunately, the Phoenix Aero Meet has remained a relatively obscure chapter in the annals of aviation history. The search is still on for additional images of this important events in the early days of aviation and of flight in Arizona.

NOTES 1. Ballooning had previously been a part of the Territorial Fair. The Phoenix Aero Meet, however, was the first event to include the miraculous new “aeroplanes.”

2. Curtis Prendergast, The First Aviators (Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1980), pp. 61-63; Ronald Geibert and Patrick Nolan, Kitty Hawk and Beyond (Dayton, Ohio: Wright State University Press, 1990), pp. 125-26.

3. C. Roseberry, Glenn Curtiss, Pioneer of Flight (Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, 1972), pp. 127-28.

4. Phoenix Gazette, November 10, 1909. 5. Ibid., November 10, 13, 1909.

6. Arizona Republican (Phoenix), February 3, I9 I 0.

7. Ibid., February 3 and 6, 1910.

8. Ibid., February 12, 1910.

9. Ibid., February 9, 1910.

10. The notice was not surprising, as the Wrights had rarely flown publicly. Despite recognition for the Kitty Hawk flights, Wilbur’s first public flight had occurred at the October 1909 Hudson-Fulton celebration in New York City. Roseberry, Glenn Curtiss, p. 208. Arizona Republican, February 4, 1910; Gazette, February 9, 1910.

11. Gazette, February 8, 1910.

12. Roseberry, Glenn Curtiss, pp. 170-77.

13. Gazette, February 9, 1910.

4. Ibid., February 7, 1910. The officials included judges Hugh Campbell, B. A. Packard, J. C. Adams, T. E. Pollock, and H. C. Lockett; timekeepers George Purdy Bullard, Billy Cook, and Shirley Christy; and starter H. I. Latham.

15. Ibid., February 11, 1910. Hamilton’s plane was damaged slightly during a cross country event and then again while landing. In the latter instance, it hit a stake leftover from O’Dell’s 1909 balloon flights.

16. Ibid., February 12, 1910.

17. Popular Mechanics, vol. 8 (April 1910), p. 480.

18. Arizona Republican, February 14, 1910.

Outstanding presentation Jeremy, thank you.

I noticed that the Katherine Stinson card refers to her as an “aviatrice”, while Amelia Earhart is often described as an “aviatrix”.

Wonderful presentation – perfect combo of excellent images & impressive, well-written research. (Stinson Field in San Antonio, TX is city-owned and serves mostly private aircraft & police helicopters. City funded huge, beautiful mural onsite featuring sisters Katherine & Marjorie Stinson, both pilots. Katherine, her sister, mother & brother operated Stinson Flying School, renting the property from city for $5 annually. US Army declined Katherine’s offer to fly aircraft in Europe during WWI, so she drove ambulances instead, met US pilot, they married, settled in Santa Fe, NM, where she became a successful architect & he a federal judge. They are… Read more »