In the mid-20th century, San Francisco stood as a beacon of the American West, blending Gold Rush era spirit with post-war optimism. Tourism, conservation, and cultural shifts motivated the creation of jumbo postcards depicting the city. At the heart of these images was Gabriel Moulin, a name synonymous with San Francisco photography.

Gabriel Moulin (1872-1945) was more than a photographer; he was San Francisco’s visual historian. Born in San Jose, he established his studio in San Francisco in 1892. For over five decades, he documented the city’s growth, triumphs, and tragedies.

Moulin’s career spanned a period of immense change, including the 1906 earthquake and fire. He captured the city’s rebuilding, its rising skyline, and engineering marvels like the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges. Collectively his work served as historical records and symbols of American ingenuity during the Great Depression, and through war and post-war eras.

Moulin’s studio excelled in both commercial and artistic photography. His subjects ranged from everyday San Franciscans to celebrities, creating a comprehensive portrait of the city’s social fabric.

Even after Gabriel’s death in 1945, his sons continued operating the studio until 2000, maintaining its reputation for quality. Today, over 500,000 Moulin Studios negatives are held by the San Francisco Public Library, providing invaluable insights into the city’s past.

The Birth of the Jumbo Postcards

The jumbo postcards we’re examining represent the intersection of Moulin’s artistry, post-war tourism, and San Francisco’s changing face. The story likely begins in the late 1940s or early 1950s, as America entered a period of unprecedented prosperity.

Gabriel’s sons, Irving and Raymond, recognized the opportunity in the tourism boom. They had a vast archive of high-quality images perfect for postcard reproduction. They partnered with Smith’s News Company, a San Francisco-based publisher and distributor, to turn these photographs into sought-after souvenirs.

The decision to produce 6×9 inch postcards was strategic. The larger format allowed for more detail and visual impact, standing out in souvenir shops. The sepia tone, even for recent images, evoked a sense of history and timelessness, appealing to tourists’ desire for authentic experiences.

Let’s examine each image in this set of jumbo postcards, exploring what they reveal about mid-20th century San Francisco and Moulin’s photographic style.

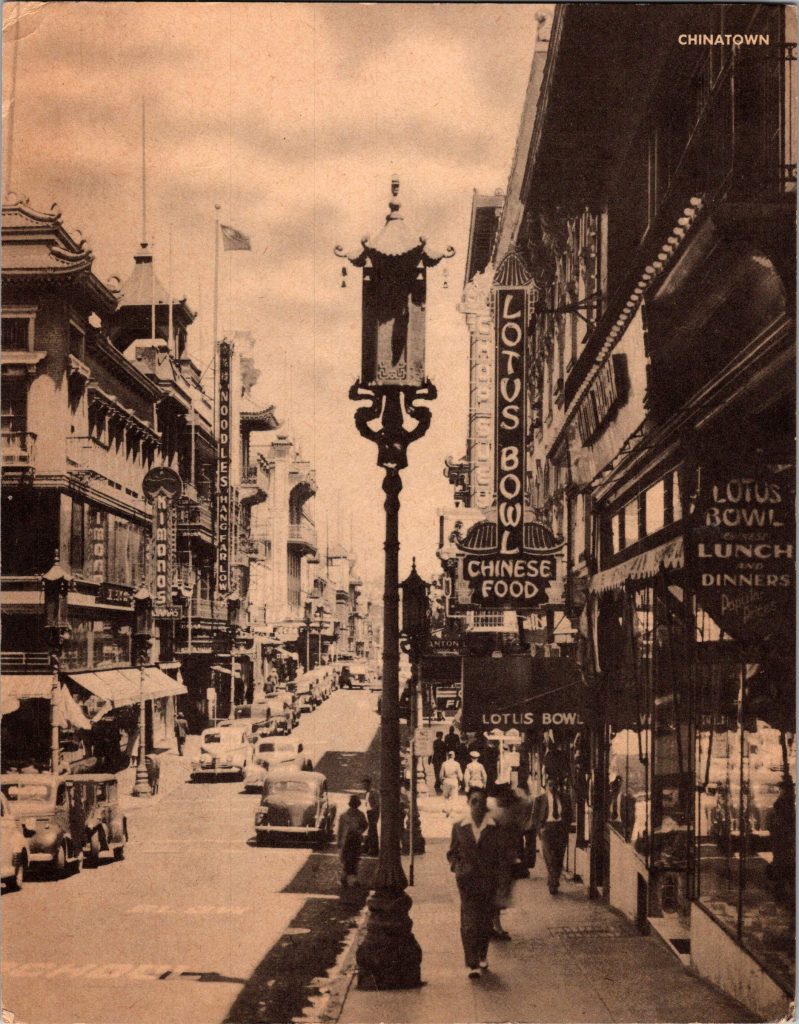

Chinatown, a Community in Transition: this Chinatown image, likely taken between 1946 and 1952, offers a glimpse into the neighborhood’s complex post-war dynamics. A well-dressed Asian man in the foreground and two men in military uniforms behind him highlight the multifaceted identity of Chinatown.

The presence of military personnel is significant, symbolizing the increasing integration of Chinese Americans into mainstream society following their wartime service. The street scene showcases prosperity and mobility, with cars lining the road and distinctive architecture creating a unique urban landscape.

This image captures Chinatown at a pivotal moment. The repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 and the War Brides Act of 1945 had changed the community’s demographic makeup. The economic revival is evident in the bustling street, with businesses catering to both locals and curious tourists.

Moulin’s composition presents a nuanced view of the neighborhood, capturing both traditional elements and signs of modernization. It offers a glimpse of a dynamic community redefining itself in post-war America.

The Bay Bridge: a Symbol of Progress

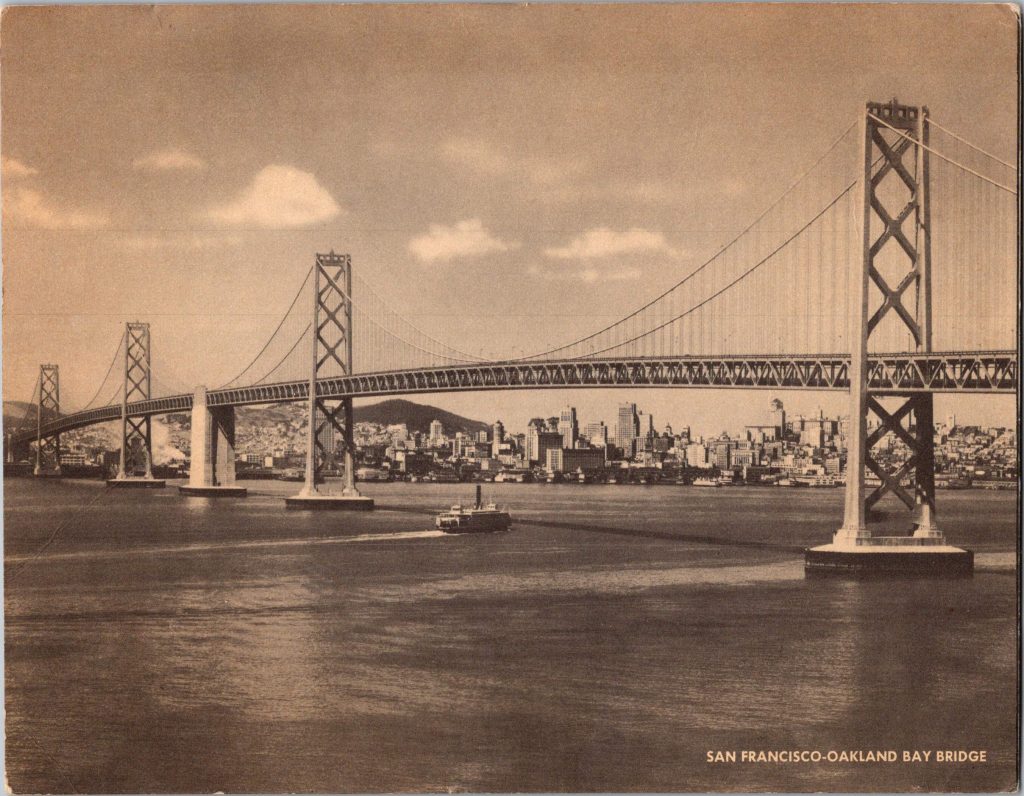

The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge postcard showcases an engineering marvel that transformed the Bay Area. Completed in 1936, the bridge was an awe-inspiring addition to the city when this photograph was likely taken in the 1940s or early 1950s.

Moulin’s composition emphasizes the bridge’s grandeur and its impact on the skyline. The photograph captures the entire span, with San Francisco’s growing downtown visible in the background. A small boat in the foreground reminds viewers of the bay’s maritime history.

This image represented more than an architectural achievement; it symbolized American ingenuity and progress. For tourists, the bridge was a must-see attraction, embodying the city’s modernity and its role in connecting Bay Area communities.

Cliff House: a San Francisco Institution

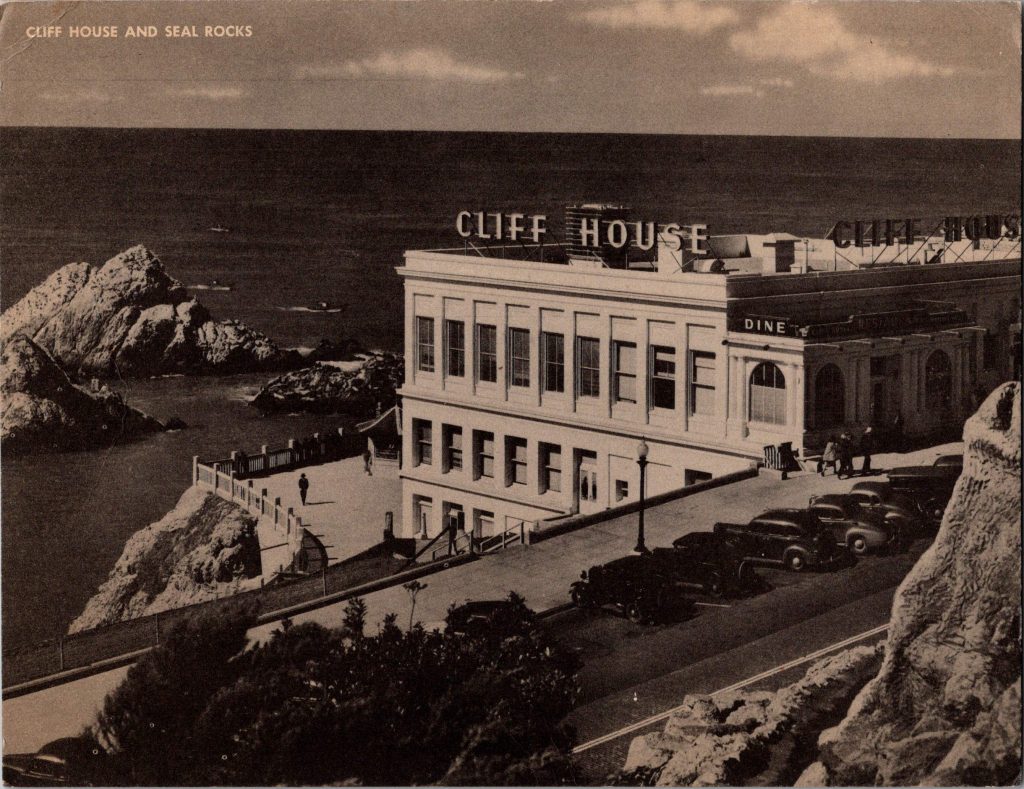

The Cliff House postcard offers a view of one of San Francisco’s most enduring landmarks. Moulin’s photograph captures its mid-20th century incarnation, with clean, modernist lines contrasting the previous Victorian structure.

The image showcases the rocky shoreline and famous Seal Rocks in the foreground, natural features that had long made this area popular. Several automobiles near the Cliff House indicate its popularity as a destination for dining, socializing, and enjoying ocean views.

Moulin’s composition emphasizes the building’s dramatic setting, seemingly rising from the rocky cliffs. This image likely appealed to tourists as a representation of San Francisco’s blend of urban sophistication and natural beauty.

Fisherman’s Wharf, the Heart of a Maritime Heritage:

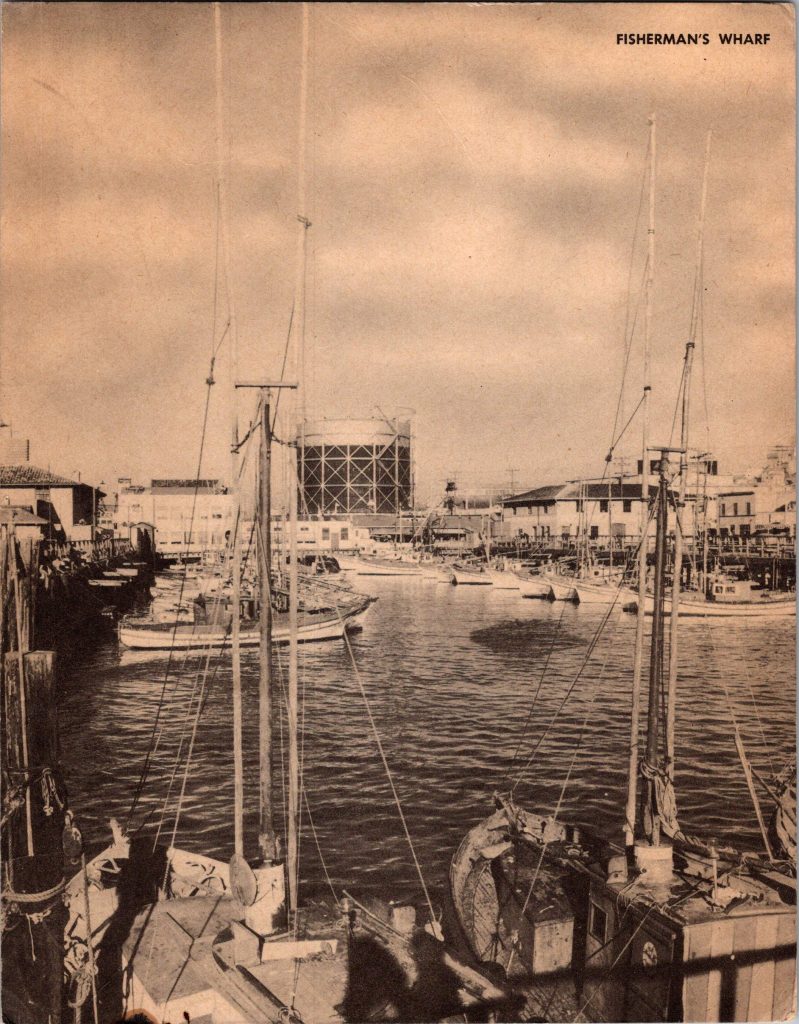

This Fisherman’s Wharf postcard offers a glimpse into one of San Francisco’s most iconic neighborhoods. Moulin’s photograph captures a thicket of masts belonging to fishing boats docked in the harbor, conveying the wharf’s bustling activity.

This view represents a moment when the area was transitioning from a primarily industrial zone to a major tourist attraction. While commercial fishing remained important, the wharf increasingly drew visitors eager to experience its maritime atmosphere and fresh seafood.

The postcard’s reverse side describes Fisherman’s Wharf as a “famous tourist center,” highlighting how the working waterfront was being marketed as a unique cultural experience. The image credits the Redwood Empire Association, indicating collaborative efforts to promote San Francisco’s attractions.

A Changing San Francisco

Together, these postcards offer a multifaceted view of mid-20th century San Francisco. From Chinatown’s cultural enclave to the Bay Bridge’s engineering marvel, from the storied Cliff House to Fisherman’s Wharf’s working waterfront, each image captures a different aspect of the city’s identity.

These postcards are windows into a particular moment in San Francisco’s history, showing a city balancing its historical roots with post-war modernization and growth. They capture the era’s optimism and energy as San Francisco cemented its place as a major American city and international tourist destination.

The Art of Postcard Photography

Gabriel Moulin’s approach to photographing San Francisco reveals much about mid-20th century postcard photography. Each image is carefully composed to showcase its subject while conveying a sense of place and atmosphere.

The Chinatown image uniquely includes people, bringing the street to life and offering a sense of the neighborhood’s vibrant culture. The Bay Bridge photograph demonstrates Moulin’s skill in capturing large-scale structures, emphasizing its sweeping lines and monumental scale. The Cliff House image showcases his ability to capture the interplay between natural and manmade environments. The Fisherman’s Wharf postcard emphasizes the dense forest of masts, creating a strong visual impression of a busy, thriving port.

Across all images, we see a consistent aesthetic defining the era’s postcard genre. The compositions are clean and direct, presenting each subject clearly and attractively. Sepia toning adds nostalgia and timelessness, helping present San Francisco as a city with rich history even as it embraced modernity.

The production and distribution of these postcards exemplify the specialized roles in the mid-20th century tourism and printing industries. Moulin Studios provided high-quality images capturing San Francisco’s essence, while Smith’s News Company handled technical aspects of production and distribution.

The choice of jumbo postcards was likely a marketing decision, allowing for more detail and making them stand out among souvenirs. This aligned with the post-war trend towards “bigger and better” in American consumer culture.

These postcards were more than souvenirs; they were advertisements for San Francisco. Tourists who bought and sent them became ambassadors for the city, sharing frame-worthy images with friends and family across the country and around the world.

Loved the history and all the background info.

Visual and written representation deepened my understanding of this professional photosnappers work.

Thanks for the great article shining light on jumbo postcards, an area too long neglected by postcard collectors.

Of these postcards, I’d most like to own the one depicting Chinatown, as it showcases a nice variety of automobiles as well as some very readable signs.