At least four women in three generations of the Muffley family of Bangor, Pennsylvania, were named Josephine Olive Muffley. The eldest, went by “Josie” [nee Josephine Humboldt] or later in life, Big Mom-Mom was born in 1843. She married Charles Muffley in 1865, only one week after his return home from his Civil War service with the 208th Pennsylvania Infantry. Josie and Charles had four children, three daughters and a son.

Their son was born in 1868. By his sixteenth birthday, James stood 6’ 3” tall. He towered over his mother and the family joke was by the time you’re old enough to vote you’ll be taller than President Lincoln.

Charles and Josie’s second child was born in the winter of 1870. Her name was Josephine Olive Muffley and her parents decided to call her Olive. James seemed to like having a little sister and it was he who dubbed her Ollie. Sadly, Ollie died at age 3 from scarlet fever.

As was often the case with that generation, the Muffley’s next daughter was named after her deceased older sister. Josephine graduated from a Pennsylvania teachers’ college in 1894. She became a kindergarten teacher and worked in just two different classrooms for the next 38 years.

James married in 1889. He met his bride in a hardware store. Her name was Alice. James and Alice had three daughters, Alice Sara Muffley in 1892, Sara Josephine Muffley in 1894, and Josephine Olive Muffley in 1899.

It was James’s youngest daughter, the fourth Josephine Olive Muffley, who became a magazine illustrator and a postcard collector. Apparently (research continues), Josephine (the fourth) married and had a daughter named Ida who attended an exclusive finishing school in the Philadelphia suburbs.

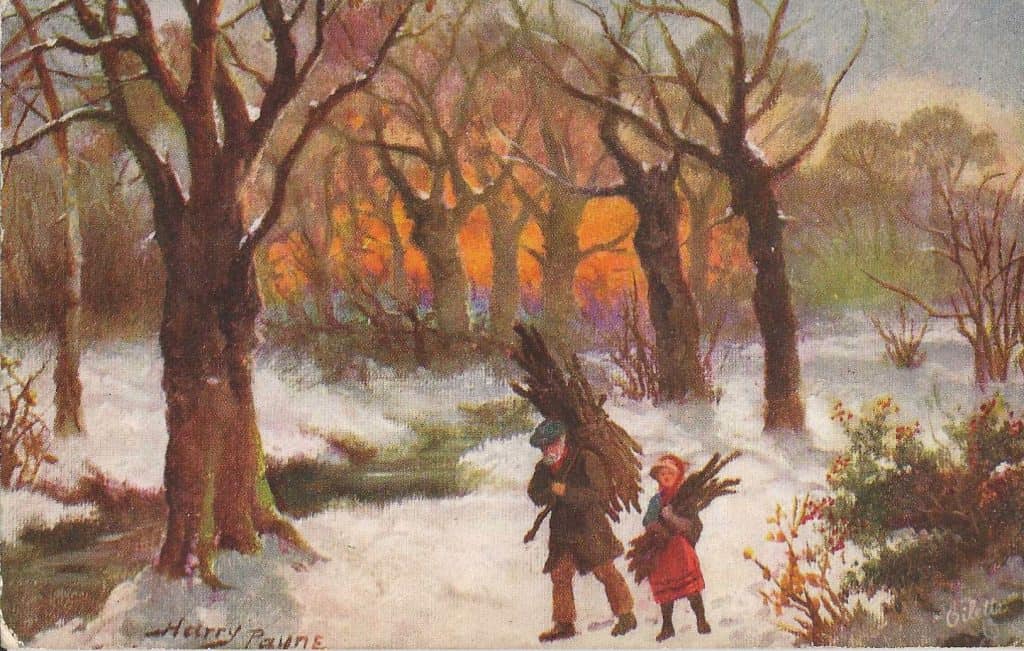

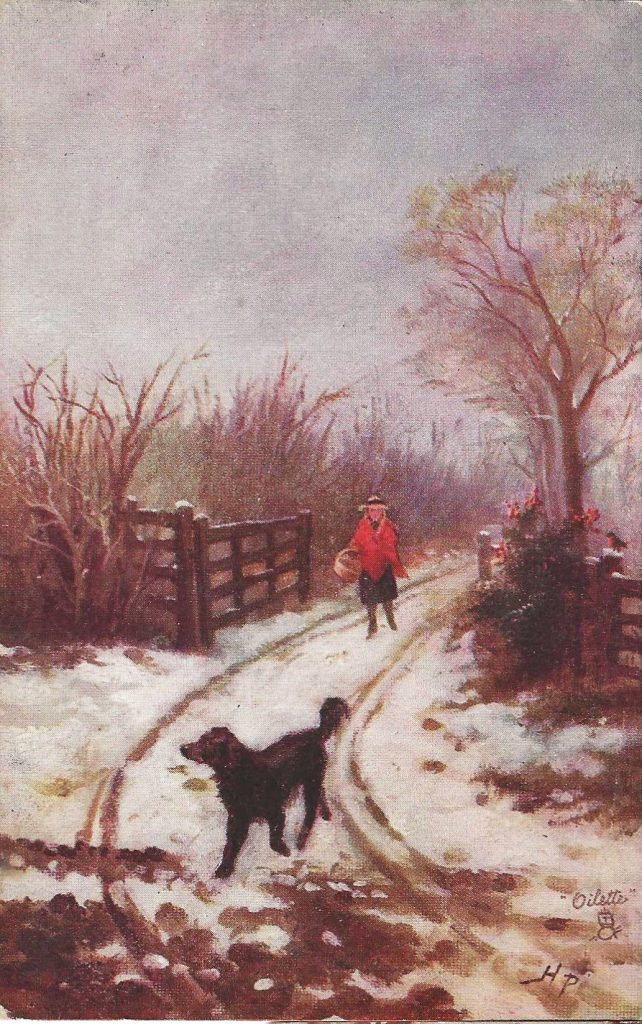

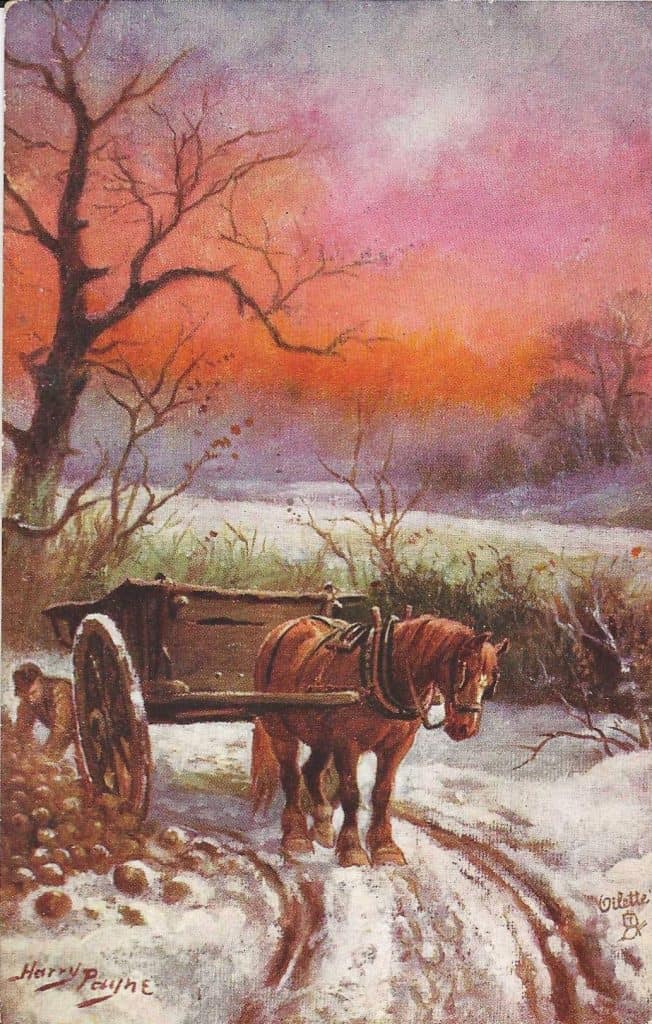

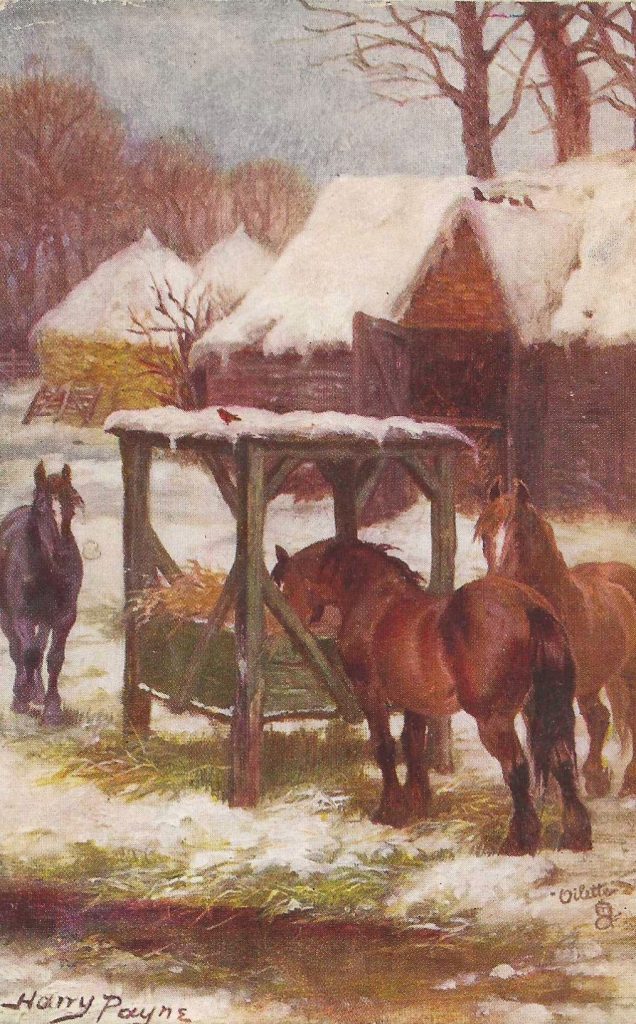

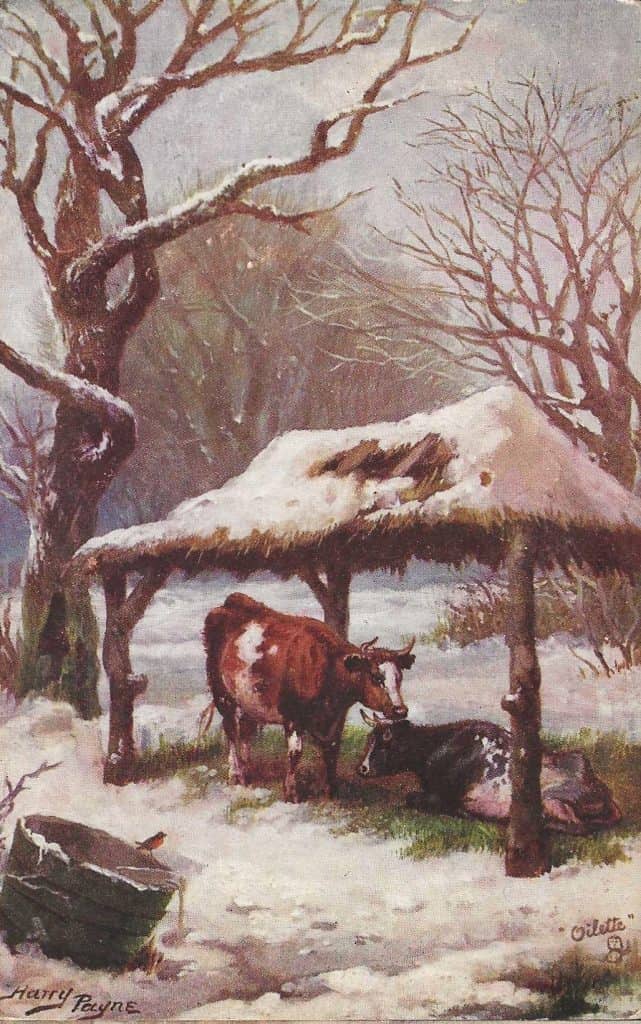

In the winter of 1931, Ida sent her mother six Tuck’s postcards. Each card shows a winter scene by the British artist Harry Payne. Each card has its own title that is somewhat unusual for a Raphael Tuck and Son’s set, but they are all part of an untitled series numbered 9028.

At first, in a letter, there was what may be called a “prelude” of the verses to follow, it read,

“Mother Dear, I think of you each day and remember well, how in the winters we would walk in the snow and then snuggle near the fireplace later at home. I have found some postcards in an old bookstore. Watch for the mail all next week. They are old, but they remind me of how, you and I know, how snowy winters transform the world into a serene wonderland, where each flake glistens like a diamond under the pale sun, and the trees stand adorned with white frost. Thoughts of our days-out came to mind and I managed to find some words to order my thoughts.

Love, Ida.”

Ida’s messages are quite poetic, and each one begins with a day of the week.

Monday. As dawn broke this day your Ida, like the girl in the picture, strolled down a quiet lane, the chill of early morning wrapped around me like a soft blanket. It seemed to be divine, but just ahead a lively dog pranced out of nowhere, his tail wagged with joyous enthusiasm. I think he wanted me to follow. The air was crisp and filled with the smell of wood smoke from many fireplaces in the village.

Tuesday. The daylight ends early in winter but like we did in our times ago we saved the unpleasant chore for last. The artist tells the same tale. A farmer is gathering mangolds as Food for the Winter for the livestock. It will likely be dark when his wife meets him at their cottage door. The same is true for me. It is dark when we get home to rest.

Wednesday. The artist portrays the horses as majestic chestnuts, who strain against the weight of the heavily laden wagon. The wheels often creak under pressure, for they are bearing the burden of grain sacks and firewood. The horses are determined, it seems, to please the master. Slowly but surely, they make their way home through the ice and snow. It is a glorious achievement.

Thursday. The artist shows that as the sun dipped low, casting a warm glow over the forest, a man and his granddaughter emerge from the woods. The crisp air fills with laughter as they searched for fallen branches, each stick becomes a treasure for their evening fire. Together, they create bonds like we have when we sit before a crackling fire that provides us with well-deserved warmth.

Friday. Out behind the barn is a rustic hayshed, a few horses graze. They present an elegant silhouette backlighted by the grey sky of dawn. Their familiar silhouettes stand as a testament to the morning’s promise. And later in the warm glow of the afternoon sun, those same horses stand contentedly by the edge of the same rustic hayshed, munching on neatly stacked bales of sweet hay. Their manes sway gently, and as they nibble the scent of dried grass fills the air.

Saturday. For some the sabbath, but for me a deadline. On this last card could we be like the mother cow as she nuzzles her calf who is seeking warmth. Their breaths create wisps of steam in the chilly air. Together, they snuggle close, finding comfort in each other’s presence amidst the cold shelter’s embrace. Why do they stay? There is no place to go. Be my mother forever, Love Ida.

What a beautiful story. I love how Ida weaves memories of her mother from the images on the postcards.

Thanks for sharing.

How nice that this set of six cards survived intact so that Ida’s words could be enjoyed nearly a century after she wrote them!

How lovely!