The Stewart lad and the Campbell lad met on their first day at Queensferry School in 1834. They were 7 years old. Because they were both named William, their teacher assigned them to seats on opposite sides of the room. Billy Stewart’s father was a ferryman. Willy Campbell’s father was also a ferryman. William Stewart inherited a pier and a small boat on the south bank of the river. William Campbell purchased his uncle’s shorter pier but had a larger boat on the north bank of the same river. Stewart’s pier was about a hundred yards west of Campbell’s, closer to the town square; Campbell’s pier was closer to the village. When Stewart ferried a passenger or a piece of freight from his pier, Campbell’s pier was his destination. When Campbell did a similar service from his side of the river, Stewart’s pier was the destination.

William Stewart, Sr. and William Campbell, Sr. knew each other and when business was slow, they would oar themselves out to the middle of the river and pass their idle time swapping stories about passengers and the gossip they had heard from the “town folk” on “their” side of the river.

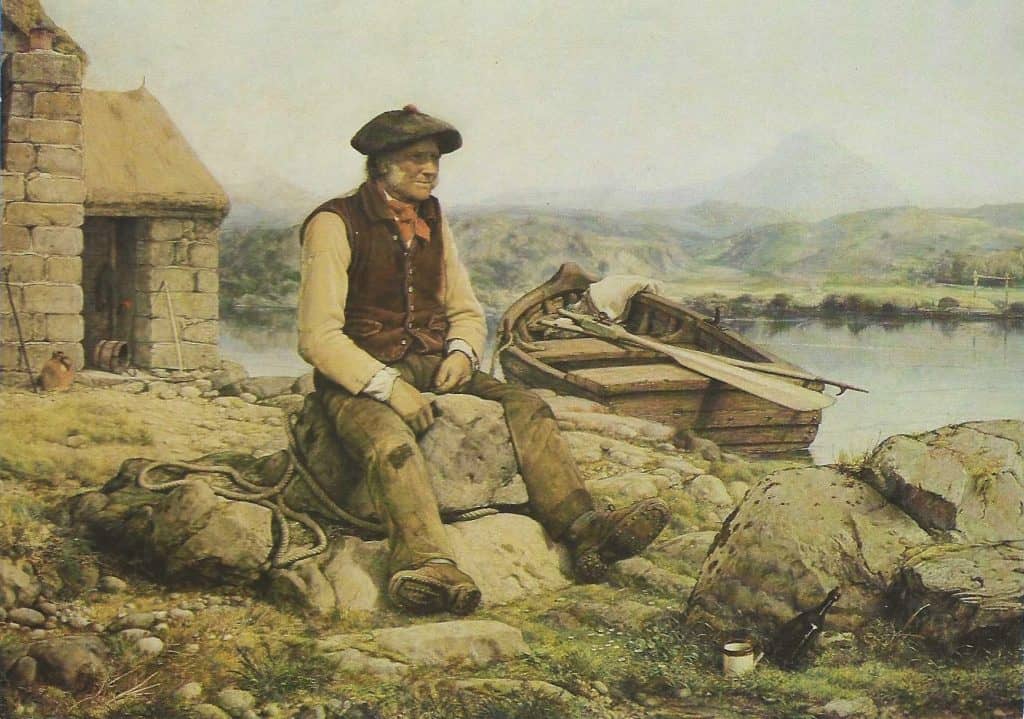

William Dyce was a 19th century British painter, his paintings are memorable, but they are few and on wide and varied topics. His landscapes can be found in museums throughout Scotland, but Dyce is often ignored by national and specialized institutions. One of his hallmark works, The Highland Ferryman, was completed in 1857. “Ferryman” captures the essence of rural Scottish life and the relationship between mankind and nature. The painting not only showcases Dyce’s artistic talent, it also serves as a window into his culture and the life of other Scots in times known as the Victorian era.

Ferrymen were essential figures in many communities, acting as vital links between different places and people. Their small boats and the service they provide are practical roles. Ferrymen were always the keepers of local lore, preservers of stories, myths, and history. As they shared tales of the land’s past, by handing down knowledge about traditions, landmarks, and natural phenomena they created a sense of identity and belonging among their neighbors.

The village on Stewart’s south-side of the river was a busy wool market. On Campbell’s north-side was the site of the shire’s best green-grocery. The south side could not exist without the north side; likewise, without the wool market, there would be no means to earn the coin to buy the groceries that were available in the north. Hence, without question, Stewart and Campbell were indispensable.

Stewart and Campbell are both dead now; Stewart in 1859, then Campbell in 1861. Their sons Billy and Willy are too. They may have a grandson or great grandson someplace in the neighborhood, but it is doubtful that either Stewart or Campbell have a descendant who is a ferryman. The Stewarts and Campbells were replaced by bridges.

The honorable career of a ferryman has been told again and again in lore and literature. There are poems, legends and tales, and even a novella, The Ferryman’s Warning, by L. Victor Gates, that recounts a time when a ferryman who served as a vital link between two villages saved the lives of hundreds by sending messages of perilous weather to his fellow countrymen. Historically, ferrymen have played essential roles in trade, travel, and cultural exchange. All made possible because they have learned the skills associated with patience and a respect for nature.

If we could return to such a time, a ferryman would get my vote much faster than that concrete and iron-beamed bridge that the city council would want to build across our river – if we had one!

***

Attention you eagle-eyed observers. Did you notice the clever way in which the artist dated his painting?

Look closely in the lower right corner of the painting. There in the foreground is an enameled tin cup. (There is also what appears to be a re-corked bottle of scotch.) The British military for a period in the early 1840s issued each recruit an enameled cup. In the army, enamel mugs were used for drinking water, coffee, and other beverages, and were often carried by soldiers in their packs or issued as part of their field rations. They were also used to hold other small items such as utensils and personal hygiene items.

In the navy, enamel mugs were used for the same purposes but were also used in the galleys of His Majesty’s Navy for cooking and serving food. They were also used in other areas of the ship, such as the mess hall, for serving drinks and meals.

The Ferryman looks to be a grizzled character. Could he be in his sixties? Perhaps the Ferryman in Dyce’s painting was a veteran. Throw him a salute!

My favourite Ferryman story is from Perthshire where the Teith bridge was built in 1535 by Robert Spittal. It appears that before the bridge was built a ferry operated nearby. Spittal turned up one day to cross the river and because he had mislaid his purse he didn’t have enough money to pay the ferryman who refused to take him over the river. It transpired that Spittal ~ out of spite ~ had the bridge built in order to put the ferryman out of business.

Thank you so much.As an ex patriot Scot I really enjoy such palatable pieces of Scottish lore

As I read this article, the Chris de Burgh song Don’t Pay the Ferryman was running through my mind. The warning not to pay the ferryman “until he gets you to the other side” echoes the myth of Charon, who ferried the souls of the dead to the underworld, and would drop you off in the “bad section” if you were foolish enough to pay upon boarding.

Quite interesting the stories that a picture can invoke! I liked the 2 Williams and their dependence on each other.

I really enjoyed reading your story it is so atmospheric and poetic, the reproductions of the paintings are beautiful, thank you very much!

Can you tell me where the date is in this picture? I keep looking and I can’t find anything.

Several weeks ago, I posted a comment saying that I cannot find the date. The artist painted the picture. He said the date was cleverly hidden in the picture. I was hoping the author would respond, but if anybody else has found it, please give me a hint.