Please indulge your editor. I have been learning about topics found on postcards and creating newsletters for more than forty years. Reference books, newspapers, my computer, and the internet have enabled me to learn a little (let’s say, the basics) about many topics. Alchemy, however, is not one of those topics. So, if you are acquainted with an early century Roman, Egyptian, or Greek, you likely know more about alchemy then anyone I know. Let’s learn this together.

First, let’s define the term, from Wikipedia, we quote:

Alchemy is an Arabic word. Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and prescientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in several pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD. Greek-speaking alchemists often referred to their craft as “the Art” or ” the Knowledge” and it was often characterized as mystic, sacred, or divine.

Common goals of the Alchemists were to purify and perfect certain materials. Chrysophobia was paramount, becoming the transmutation of basic metals like lead into noble metals, particularly gold; next came the creation of an elixir of immortality, and finally the alchemists wanted to create panaceas able to cure all disease.

The Wikipedia article is extensive – nearly 15,000 words – that would be, by the standards we use here at Postcard History Online Magazine over six weeks’ worth of articles.

***

Now that we know what Alchemy is, we need to delve into one practitioner and learn from the postcards that illustrate his primary treatise: the Splendor Solis (In English: The Splendor of the Sun.

The man was Salomon Trismosin. The facts of Trismosin’s life are mostly unknown. Even less becomes evident after a thorough study of the legendary tales of his journeys found in works attributed to him. His tales, according to one historian, have little value other than providing an “aura of historicity” to the texts attributed to him. An aura of historicity describes the quality of an object, idea, or even a person that gives it a sense of being ancient, unique, and deeply connected to a past tradition or history.

As another matter of concern even the name Salomon Trismosin is likely a pseudonym. However, be his name real or imagined, he is credited as the author and creator of the art shown on a set of 22 postcards published thirty years ago in Köln (Cologne), Germany. The cards are 6 3/8” x 4 3/8” and of a very high quality.

Again, from Wikipedia, we quote:

The German occultist, Franz Hartmann claimed the actual name of Trismosin was “Pfieffer” (though he provides no evidence for this claim) and the Australian historian Stephen Skinner identifies him with Ulrich Poysel, who was a teacher of Paracelsus. They, at least partially agree, that most of the sources of data on Trismosin’s life comes from a short autobiography written in Aureum Vellus.

Finally, we quote:

“Aureum Vellus” is Latin for “Golden Fleece” and refers to both a mythical object of great value and a term used in various contexts, including the title of an alchemical text by Salomon Trismosin. The phrase symbolizes high value, extraordinary quality, and the difficult journey of achieving perfection.

***

Trismosin’s The Splendor of the Sun

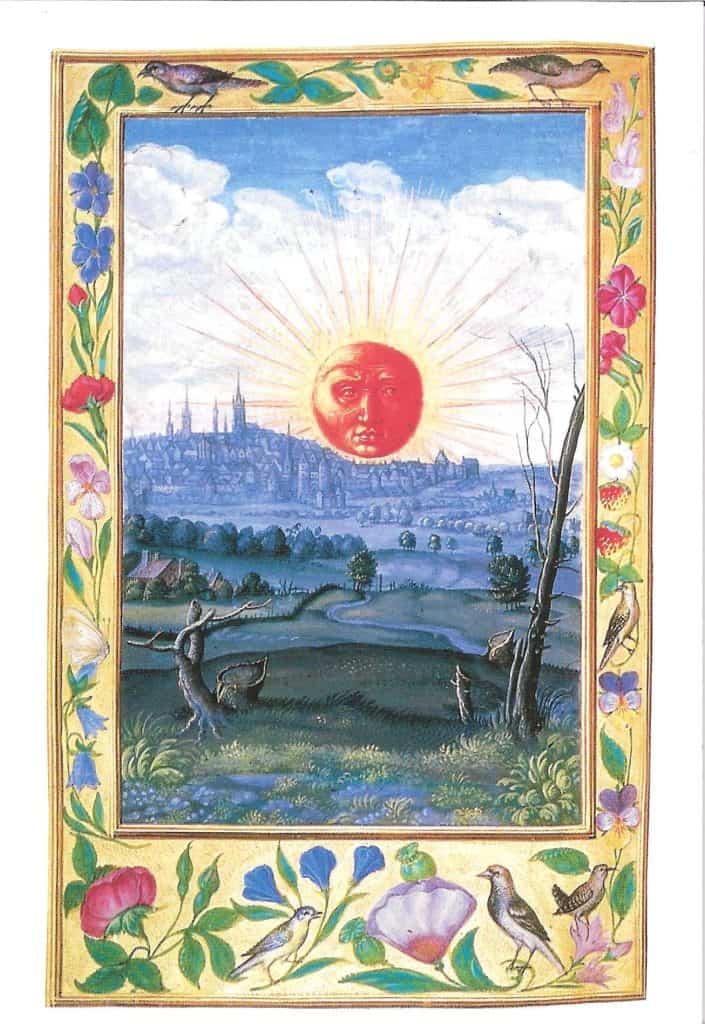

Trismosin’s The Splendor of the Sun is an inspirational work in alchemical literature, emphasizing the transformative power of the sun as a symbol of enlightenment and spiritual awakening. The text explores the sun’s role in alchemy as the source of life, vitality, and divine illumination. Trismosin used poetic language and allegorical imagery to depict the process of inner purification and the pursuit of wisdom. Central to the work is the idea that understanding the sun’s mysteries leads to spiritual immortality.

The work reflects the Renaissance fascination with esoteric knowledge and the belief that material transformation mirrors spiritual transcendence.

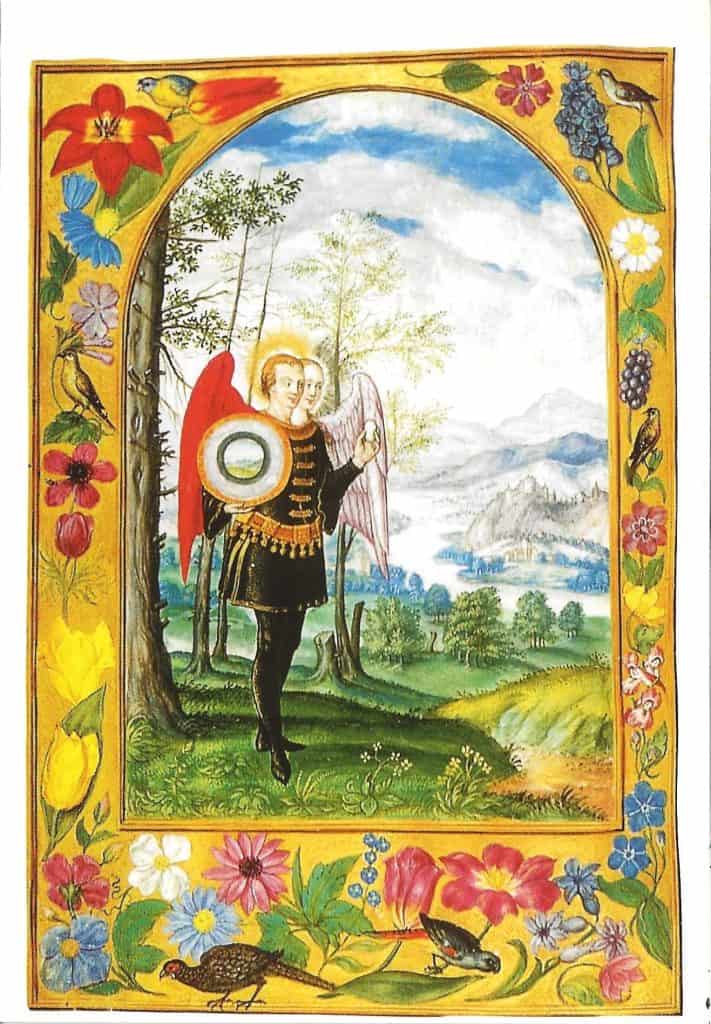

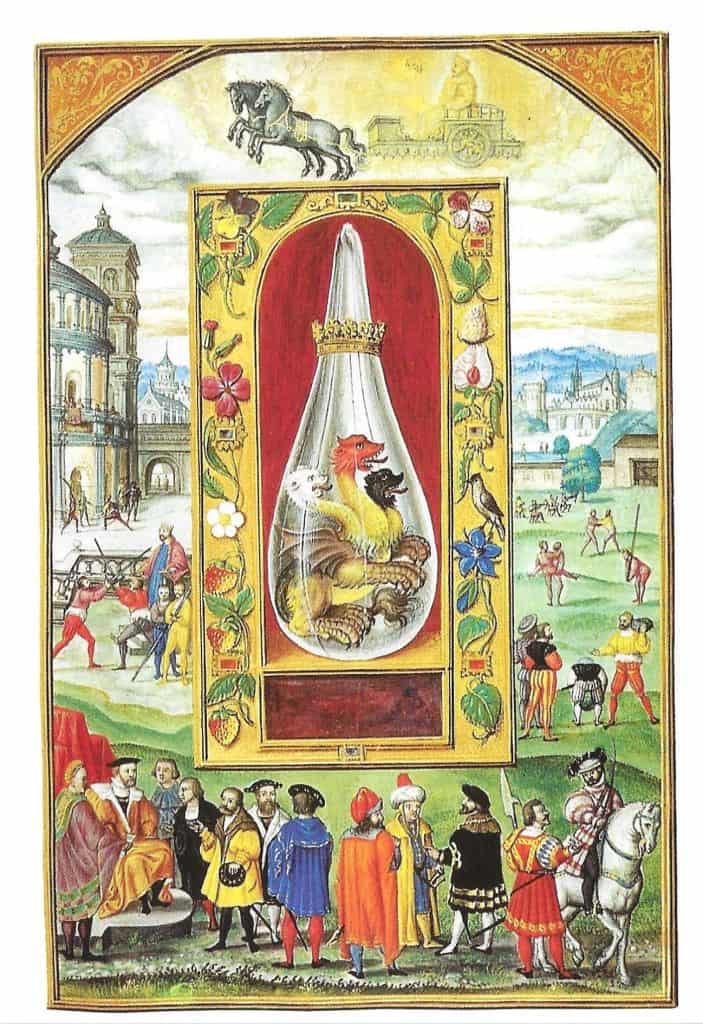

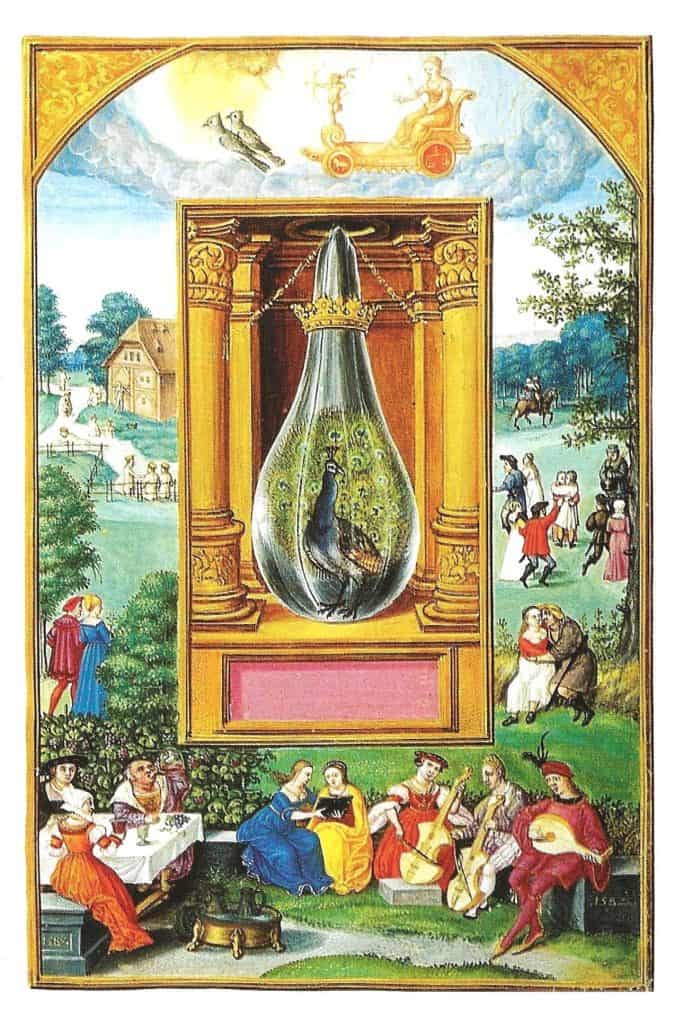

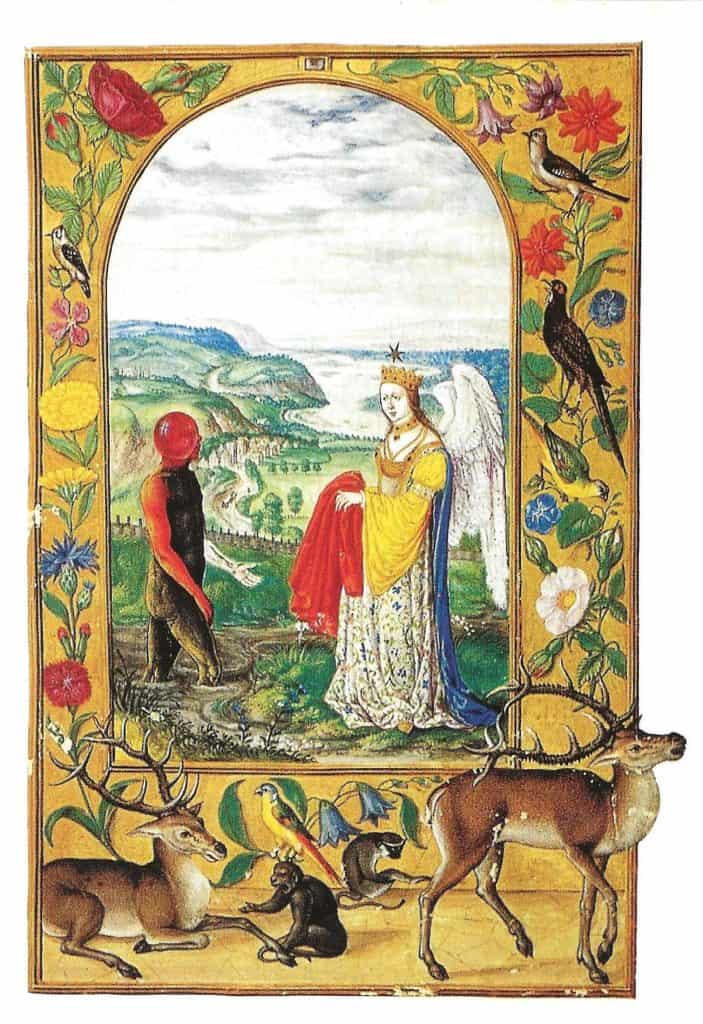

In summary the work is a sequence of 22 elaborate images, set in ornamental borders and niches. The symbolic process shows the classical alchemical death and rebirth of the king, and incorporates a series of seven flasks, (two of which are seen here) each associated with one of the then-known planets. Within the flasks a process is shown involving the transformation of bird and animal symbols into the Queen and King. Although the style of the Splendor Solis illuminations suggest an earlier date, they are likely of the 16th century.

The ultimate lesson comes at the closing; it spells a universal truth showing that The Splendor of the Sun is a profound allegory for personal growth that is true when inner illumination begins.

This lesson in alchemy has done very little to aid in my understanding of the topic, but don’t you agree that the cards are beautiful examples of 15th century art?