John Brown’s body lies a-mold’ring in the grave

John Brown’s body lies a-mold’ring in the grave

John Brown’s body lies a-mold’ring in the grave

His soul goes marching on

Glory, Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory, Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory, Glory! Hallelujah!

His soul is marching on.

Traditional folklore holds the lyrics and melody were created by a group of Union soldiers from the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Battalion, and put to the music of the Episcopalian hymn, “Say Brothers.”

The song was considered to be too coarse and irreverent for polite company and was almost immediately done again set to the music of, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

***

John Brown was born in Connecticut on May 9, 1800. His father eventually sired 16 children, including ten sons, with three wives. The family moved several times, including a short stint in Ohio, then considered a wilderness, but also an anti-slavery bastion. The family was in Connecticut again when 16-year-old John left home to go out on his own.

At times Brown was an ordained preacher, a surveyor, the proprietor of a tannery, and an owner of several businesses. His anti-slavery views formed early and crystalized as he and his family relocated to (among other states) Ohio and Pennsylvania. Brown had five children with his first wife and 13 with his second wife, overall fathering ten sons, not all of whom survived to adulthood.

The 1837 mob murder of Elijah Lovejoy, an abolitionist newspaper publisher from Illinois, led Brown to proclaim that “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.”

Brown moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1847 to establish a wool distribution business. While there, Brown met Frederick Douglass, with whom he argued for more decisive action to overturn slavery against Douglass’s preference for a non-violent approach.

In response to the Fugitive Slave Act, Brown formed the “League of Gileadites” (Mount Gilead was where Gideon was led by God to save the Israelites). Brown emphasized his resistance to that Act, writing that “no jury can be found in the Northern States that will convict a man for defending his rights to the last extremity. … should one of your number be arrested, you must collect together as quickly as possible, so as to outnumber your adversaries.”

In 1855 Brown and five of his sons moved to Kansas to fight the pro-slavery forces going to Kansas from Missouri. They perpetrated the Pottawatomie Massacre where five men were killed in response to an attack on the town of Lawrence. Northern newspapers wrote wild exaggerations of this and other events to create the term “Bloody Kansas” when in fact only between 55 and 200 people were killed over the four years before a free-soil state constitution in 1859 paved the way for Kansas’s admission to the union in 1861.

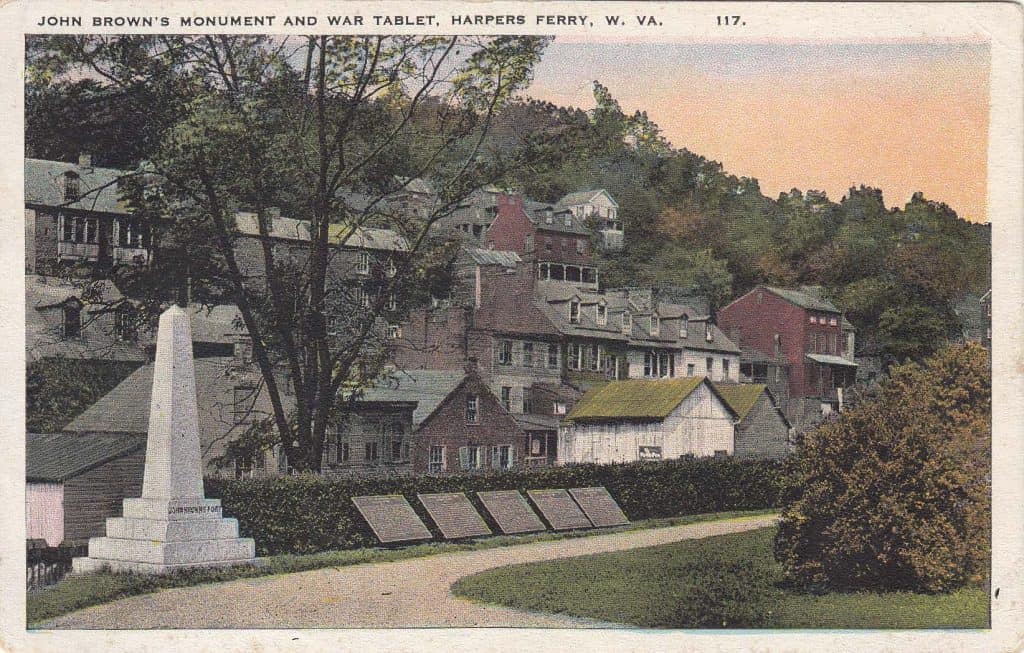

Brown had long dreamed of striking a major blow against slavery. After his time in Kansas, he focused on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), for its large supply of weapons and ammunition, which he planned to distribute to slaves he freed so that they could begin a widespread slave rebellion.

For more than a year, Brown travelled extensively to raise funds for the raid. In that time he decided to change his appearance from clean-shaven to bearded. He planned the raid meticulously and after a few false starts, he launched his raid on the armory on the night of October 16, 1859.

Brown led his force of 22 men who cut the telegraph line, overwhelmed the armory’s single watchman, took several local men hostage, and passed the word to local slaves that they were freed.

In a tactical blunder, Brown stopped a train that came through the town but then let it go. At the next station the train’s conductor telegraphed the railroad’s headquarters, which then contacted the governor of Virginia and President Buchanan.

As planned, Brown moved his hostages into the railroad’s nearby engine house. By the afternoon of October 17, marines and regular U.S. army troops under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee had surrounded the building.

Lee sent an emissary to tell Brown that the lives of the raiders would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and the military broke through the engine house door, fought a three-minute skirmish, and took Brown and his raiders captive. Four townsmen, one marine, and three of Brown’s men died in the firefight.

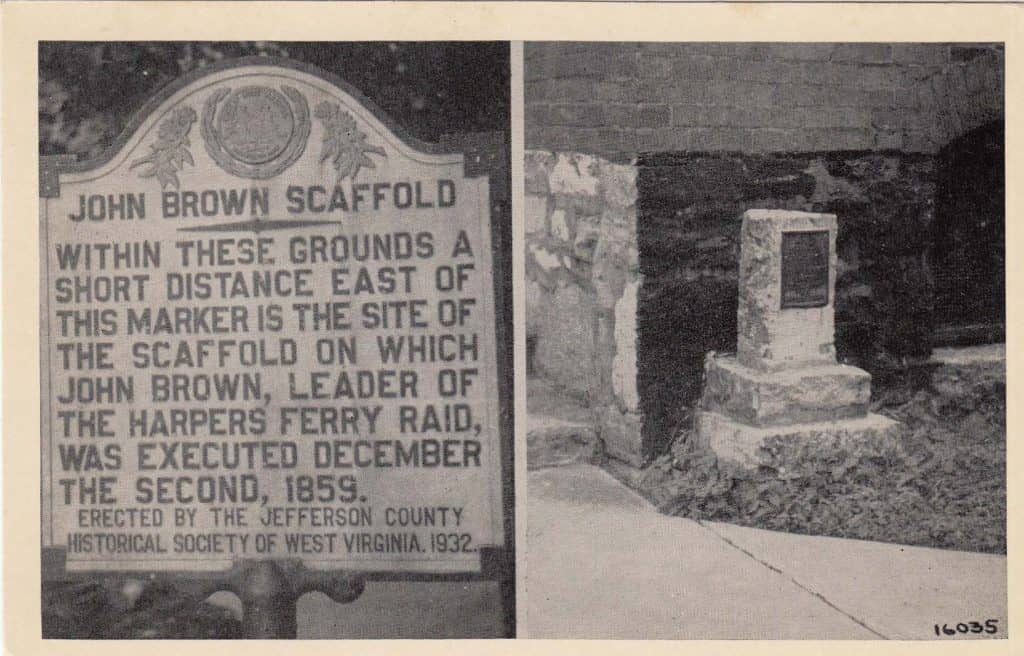

A one-week trial ending on November 2 found Brown guilty of treason (against Virginia, which had such a law) and those raiders who had been captured were found guilty of murder as well as treason. Brown’s execution was delayed one month to December 2 as required by Virginia law.

Brown used that time to meet supporters, respond to letters written to him, and give interviews to reporters whose articles built the story of Brown as a martyr. Brown’s wife wrote Virginia’s governor pleading to take his body home to North Elba. In granting this request, Governor Wise rejected several unsavory offers for Brown’s body.

It was a chilly windy morning when Brown sat on his coffin waiting to take the short trip to the gallows. More than 1,000 militia were arrayed along the route and at the execution site to prevent any rescue attempts.

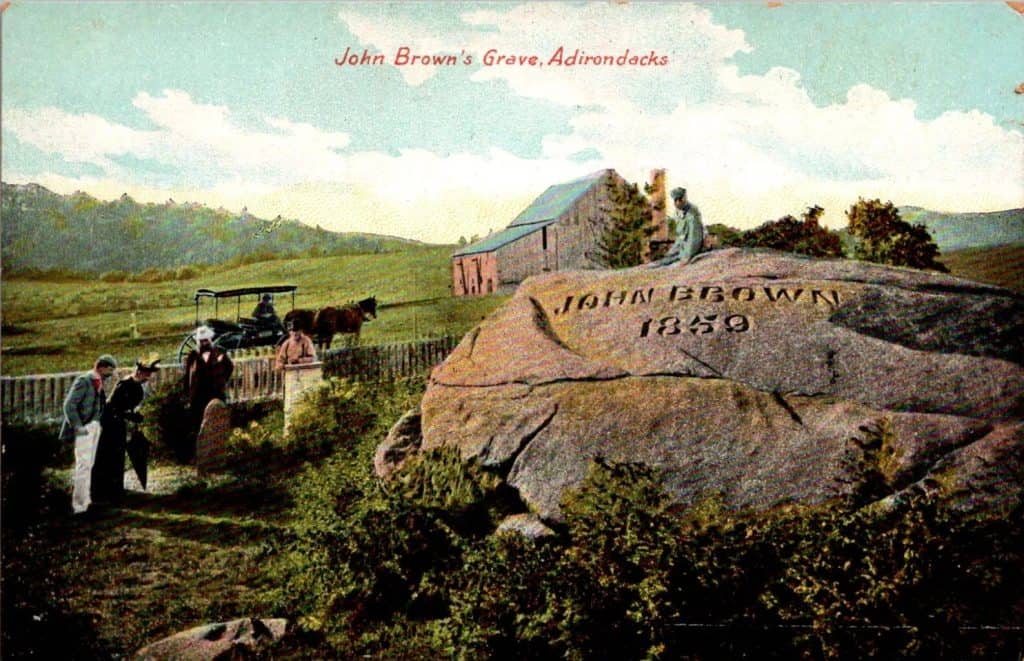

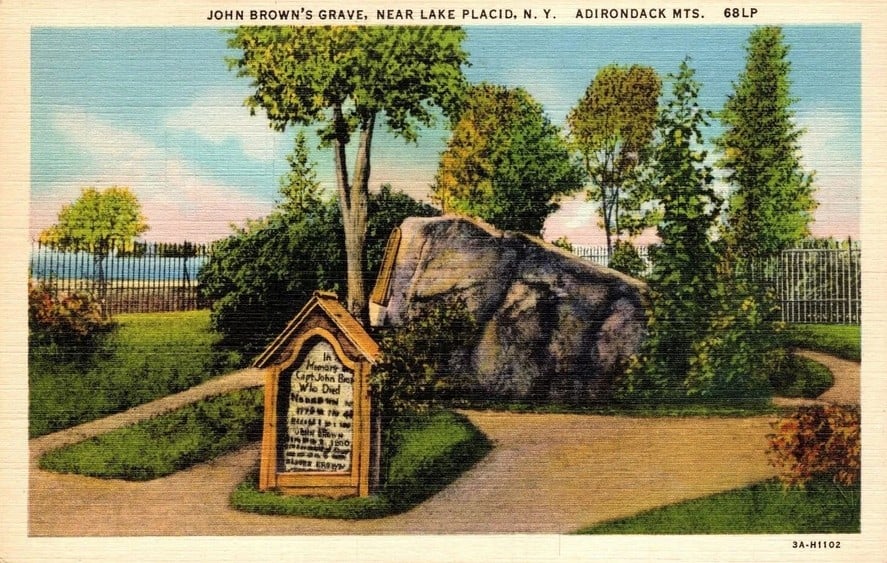

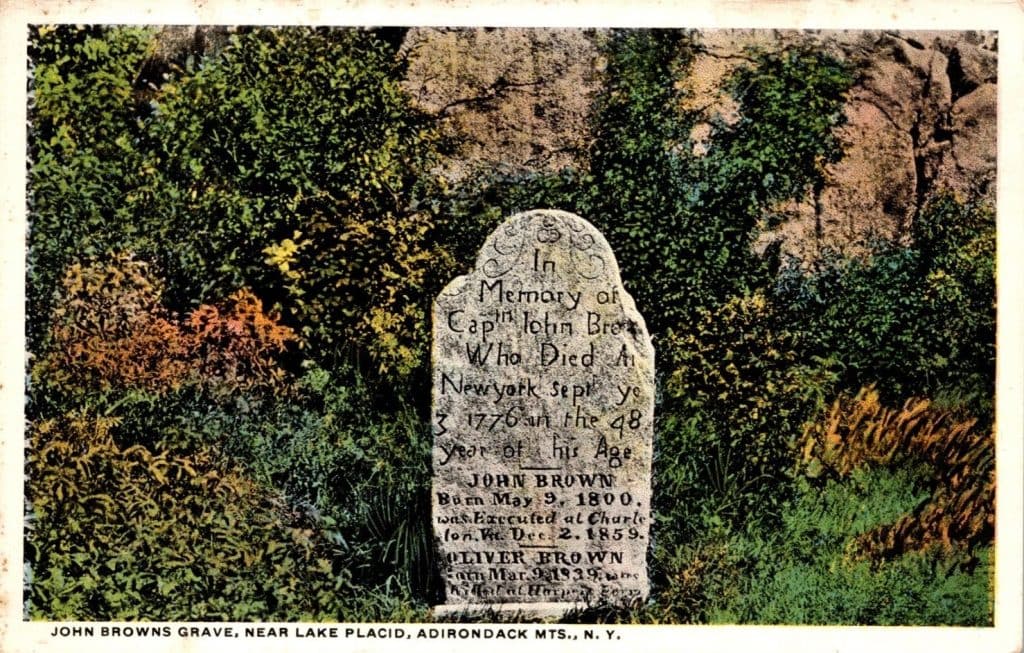

It took five days to transport Brown’s body to the farm in North Elba, New York. He was buried next to a large bolder on the farm.

***

Of the first twelve Presidents of the United States, eight owned slaves while in office, two (William Henry Harrison and Martin Van Buren) owned slaves only prior to serving as President, and two never owned slaves (John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams).

By 1820, western settlement had expanded the original 13 states to 22 and tensions over the issue of slavery had grown. Congress passed the Missouri Compromise, drawing a line at the thirty-sixth parallel (36° 30´), above which slavery was forbidden, while below that line slavery was permitted.

The Missouri compromise admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. By 1850, however, outright conflict over slavery had developed and another compromise was needed to avert what many feared could be civil war.

The Compromise of 1850 was composed of a set of five laws: California was admitted as free, Utah and New Mexico were to decide the question by referendum (“popular sovereignty”), the slave trade was abolished in Washington, D.C., and a Fugitive Slave Act required Northerners to assist in capturing escaped slaves.

In 1854 two new territories, Kansas and Nebraska, were awaiting admission. Congress decided to leave the question of slavery to a referendum called “popular sovereignty.” Effectively, the Missouri Compromise had been repealed.

Responding to burgeoning agitation over slavery, Congress passed the Compromise of 1850. Part of the compromise was the Fugitive Slave Act, which effectively allowed free-lance slave catchers to kidnap free-born or manumitted black people and sell them to plantation owners.

***

The wealthy political reformer and abolitionist Gerrit Smith, who owned a huge swath of land in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, offered families land in “Timbuctoo,” a farming community for black homesteaders in the remote town of North Elba (near what is today Lake Placid). Brown had moved his family there in 1851 and it was the family’s forever home.

***

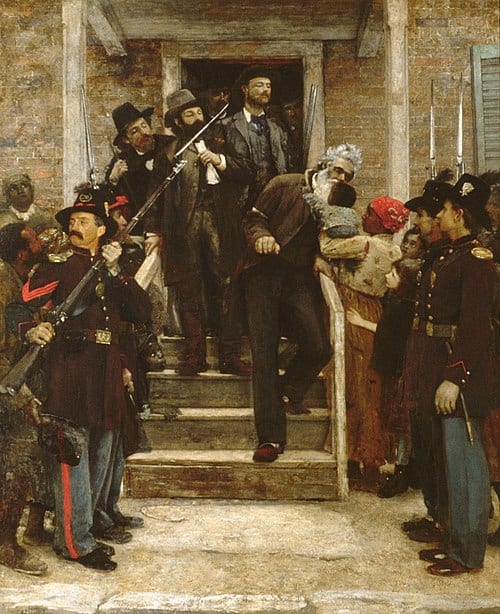

The Last Moments of John Brown. A New York businessman and abolitionist, Robbins Battell, in 1882 commissioned a painting of Brown being led down the steps from his jail to his execution, stopping to kiss a baby offered to him by its mother.

Artist Thomas Hovenden began work on the painting and did extensive research using contemporary sources.

Battell sent Hovenden a copy of the fiction-heavy account of Brown’s execution published in 1859 by the New York Tribune and Hovenden took his patron’s interest to heart. Battell was pleased with the painting and paid Hovenden several thousand dollars more than what Hovenden expected and allowed the artist to copyright the work. The scene was unlikely to have happened since security at the jail did not allow non-military people anywhere near Brown.

***

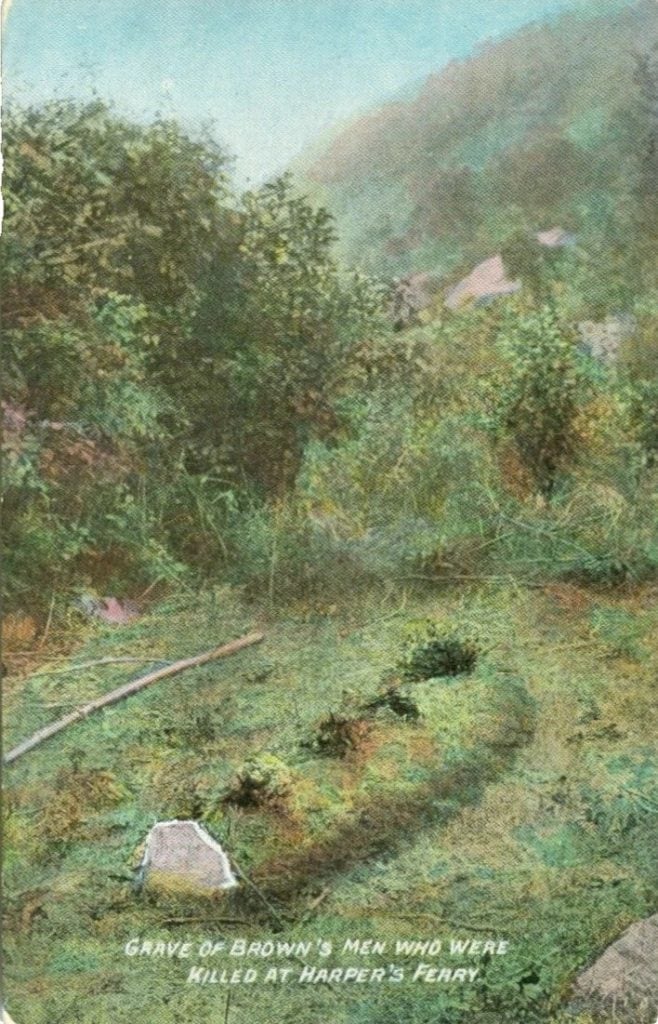

Gathering the remains of Harpers Ferry raiders and reburial at a North Elba farm. While John Brown’s body was given to his wife, the remains of his raiders were not handled with such care. After their executions, some were taken as cadavers at medical schools. Over the next 40 years an effort was made to bury what remains could be found in a common grave near Brown’s grave on August 30, 1899, at a memorial event for the abolitionist cause.

The John Brown Farm State Historic Site includes the home and final resting place of John Brown. It is located on John Brown Road in the town of North Elba, 3 miles southeast of Lake Placid, NY. Brown moved here in 1849 to teach farming to escaped African Americans.

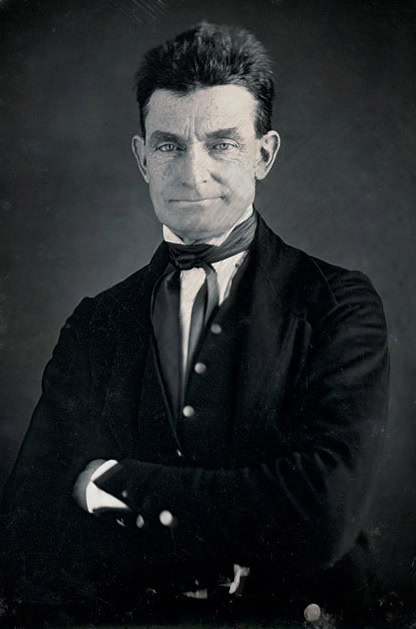

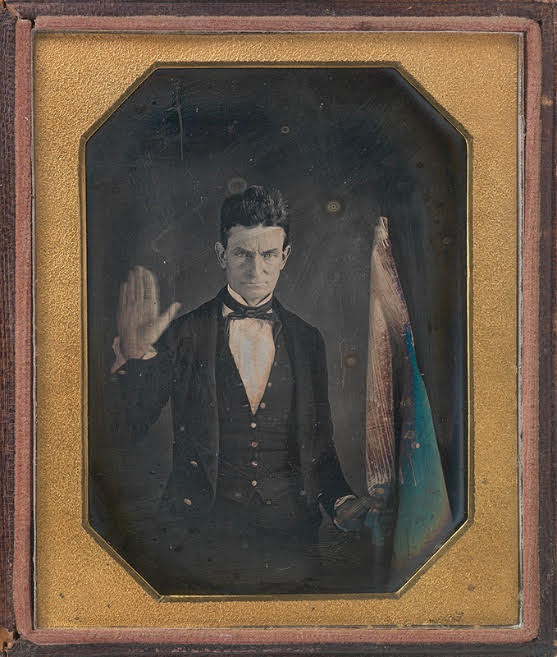

Photo of John Brown taken by African American daguerreotypist and fellow abolitionist Augustus Washington between 1846 and1847. His pose may dramatize his antislavery activism, as Brown’s right hand could be reciting his public pledge to dedicate his life to the destruction of slavery while his left hand holds what may be the flag of the “Subterranean Pass Way,” his militant alternative to the Underground Railroad.

Quite enjoyable article despite the sad ending for Brown. Thank you!

Never knew the story of John Brown .Thankyou

A most enjoyable and informative article. In addition to the images shown there are a number of postcards showing Brown’s life and times in Torrington, CT where he was born.