Marie and I had a pleasant surprise on our way home from a weekend trip last month, but hold that thought, I’ll be right back. I want to advocate for free education. Learning should be free in every way. Not just in public schools, but in museums of every kind, libraries, art institutions – everywhere we can learn something new – especially on the Internet.

Americans today are being squeezed. One of my pet-peeves is that when a museum administrator discovers a short-fall in revenue sources the first thing he/she does is suggest to the Board of Trustee that admission fees or membership dues be increased – many of which are already too high. One museum membership I recently ended was when a $35 family membership was increased to $135.

What they should think about is making a museum visit much more affordable. Here’s a novel idea – reduce admission fees by half so more people could afford to bring the whole family to the museum.

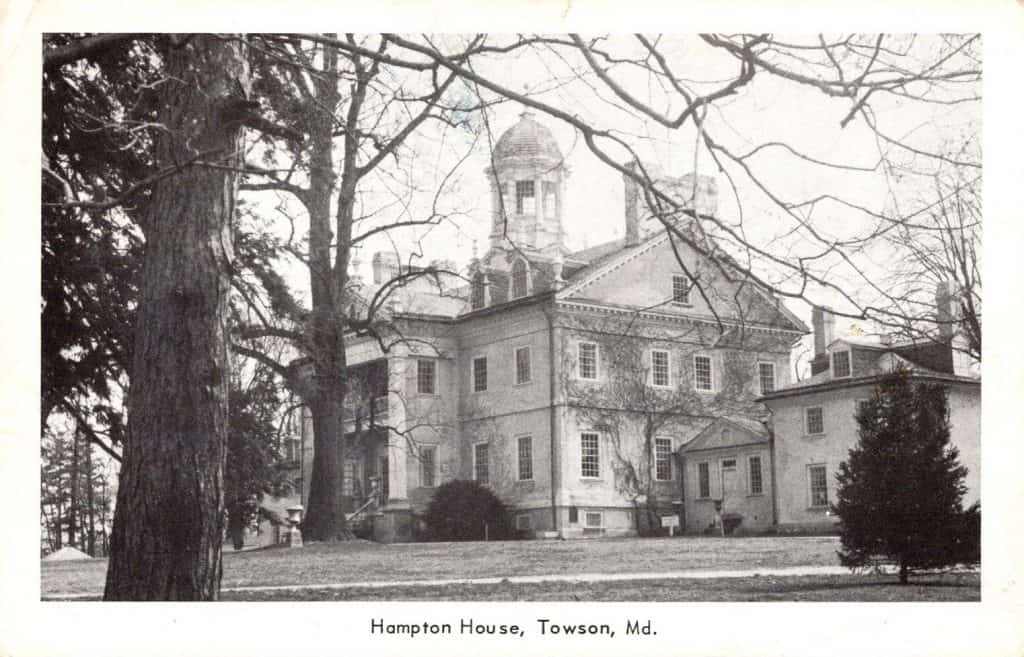

Returning to the surprise I mentioned . . . we found ourselves on Interstate 695 (the ring road around Baltimore, Maryland). The sun was bright that day and we were headed straight into the sun – the glare was blinding. I surrendered to mother nature and left the highway at the next exit. We found ourselves in the Baltimore suburb of Towson. While we waited for a traffic light, I saw a sign to the Hampton (House) Historic Site. It was only 2:30 so we followed the arrow.

We turned into a magnificent driveway and found ourselves at the ancestral home of the Darnell family – Hampton House – part of the National Park Service. Our surprise was that admission was free!

Editor’s note: the text that follows is quoted (and mildly edited) from the United States National Park Service website (www.nps.gov/hamp/learn/historyculture/index.htm)

for the Hampton (House) National historic site, Maryland:

Hampton National Historic Site today preserves the core of what was once a vast commercial, industrial, and agricultural plantation that encompassed nearly 25,000 acres in northern Baltimore County and where hundreds of people were enslaved. Without the wide range of workers and their contributions, Hampton could not have existed at all. Interpreting all these individuals—enslaved, indentured, and free—helps connect every aspect of Hampton, the buildings, grounds, gardens, and objects.

Starting with indigenous communities migrating across the land that is now Baltimore County has been travelled by people for many years. European settlers arrived in the 1600s, including the Darnall family who were granted a 1,500-acre tract of land in northern Baltimore County which they named “Northampton,” carrying the name with them from England.

In 1745, Colonel Charles Ridgely, a third generation Marylander, purchased the Northampton tract, initially as a tobacco plantation. In 1761 Colonel Ridgely and his two sons (John and Captain Charles) established an ironworks, the Northampton Furnace, where workers mined iron ore and limestone, made charcoal to fuel the blast furnace, refined and cast ore to make pig iron.

During the American Revolutionary War, the ironworks produced munitions such as cannons and cannonballs for the Continental Army. This profitable wartime industry created considerable wealth for the Ridgelys.

Amid this economic hub, immediately after the close of the Revolutionary War in 1783 construction started on Hampton mansion, a massive Georgian style house set atop a hill. Built at the direction of Capt. Charles Ridgely, at 24,000 square feet the house may have been the largest private residence in the United States when completed in 1790.

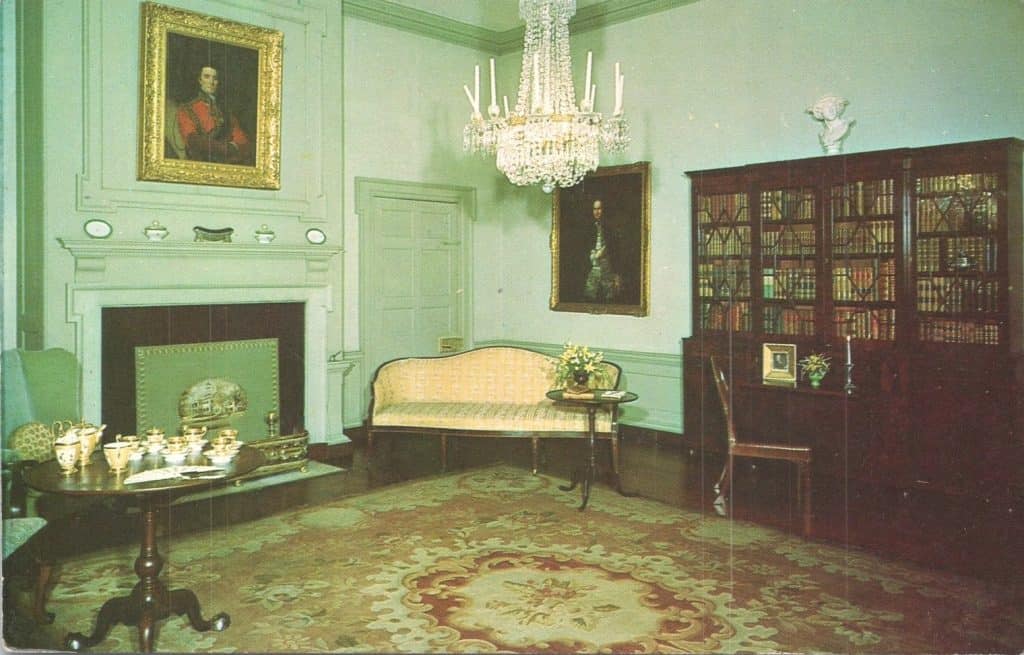

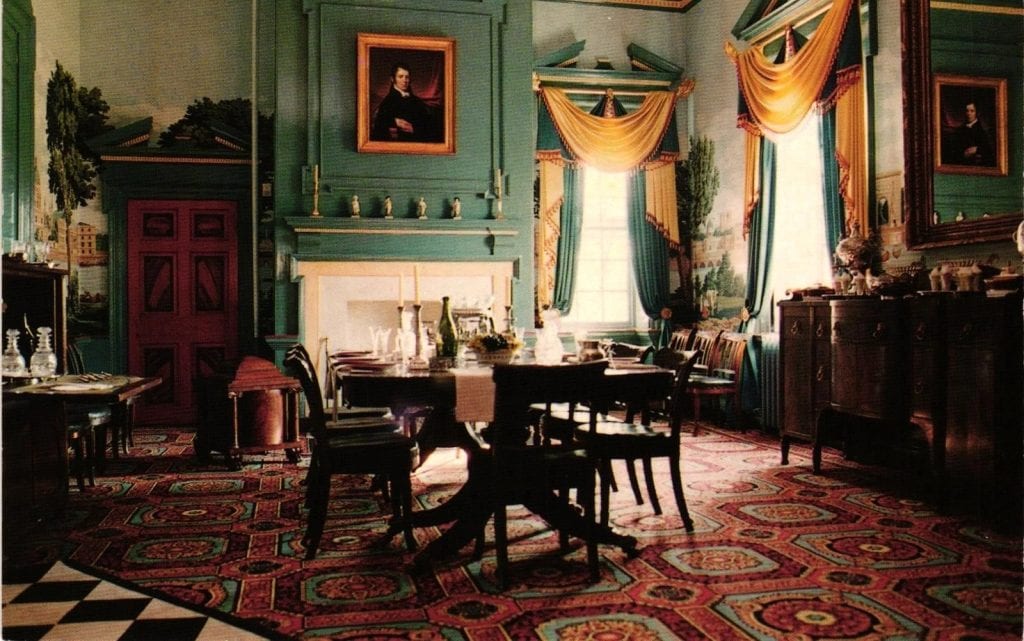

The imposing architectural masterpiece became a symbol of wealth. The elegantly furnished mansion was set amid formal gardens and carefully landscaped grounds, making it an island of tranquility.

Having no children of his own, Captain Charles Ridgely left his nephew, Charles Carnan Ridgely, as the business partner and heir to Hampton. Under the proprietorship of Carnan Ridgely, the 25,000-acre Hampton plantation reached its height of prosperity. The ironworks continued to be the main source of the family’s wealth, supplemented by farming, orchards, mining, marble and limestone quarries, mills, and mercantile interests.

After Carnan Ridgely’s death in 1829, the ironworks ceased operation, and Hampton transitioned to a large, Southern-style plantation incorporating fields of grains, orchards, and herds of livestock.

Over time, the combination of the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States, economic downturns, and division of property among heirs reduced the plantation to 1,000 acres. By the 1920s, suburbs were encroaching and farming became less viable.

The Great Depression and World War II finally led the Ridgely family to sell the house and part of the remaining property to the National Park Service in December 1947. Hampton National Historic Site was established in June 1948 “on outstanding merits as an architectural monument,” making it the first historic site of its kind within the National Park Service. This designation paved the way for the establishment of the National Trust for Historic Preservation the following year. After a much-needed restoration, the site was officially opened to the public in 1950.

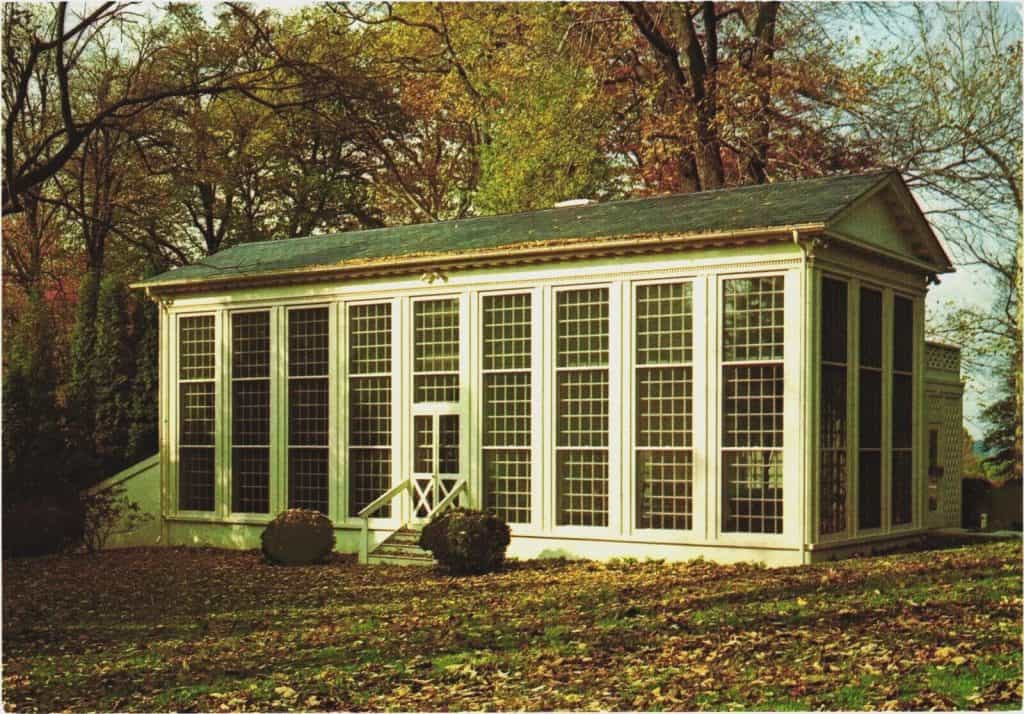

Today the park encompasses roughly 63 acres including the historic mansion, gardens, several farm and domestic outbuildings, quarters of the enslaved, and family cemetery. These can all be explored to learn the many stories and voices of Hampton National Historic Site.

Ray,

I always enjoy your articles. This one is close to home. I can visit the Hampton House as I return home from my many trips to Martland.

Thank you for sharing

Walt