It was June 1946. The National School Lunch Act was passed by both the House and the Senate. The House approved the bill with a roll-call vote of 370–11. (I did not research beyond the vote-count since I knew learning the names of politicians who would vote against giving a child a school lunch, especially in a time when a half-pint of milk cost 3¢ or if the kid liked chocolate milk, 5¢, would only make me angry.) The Senate had passed the final version by a voice vote on May 24th.

When President Truman signed the legislation, he said the enactment of this bill “strengthened the nation through better nutrition for our school children.” His remark was indeed rhetorical since it was common knowledge that most of the country in the post-war years was measurably insecure in many ways: housing, nutritionally, medically, and educationally.

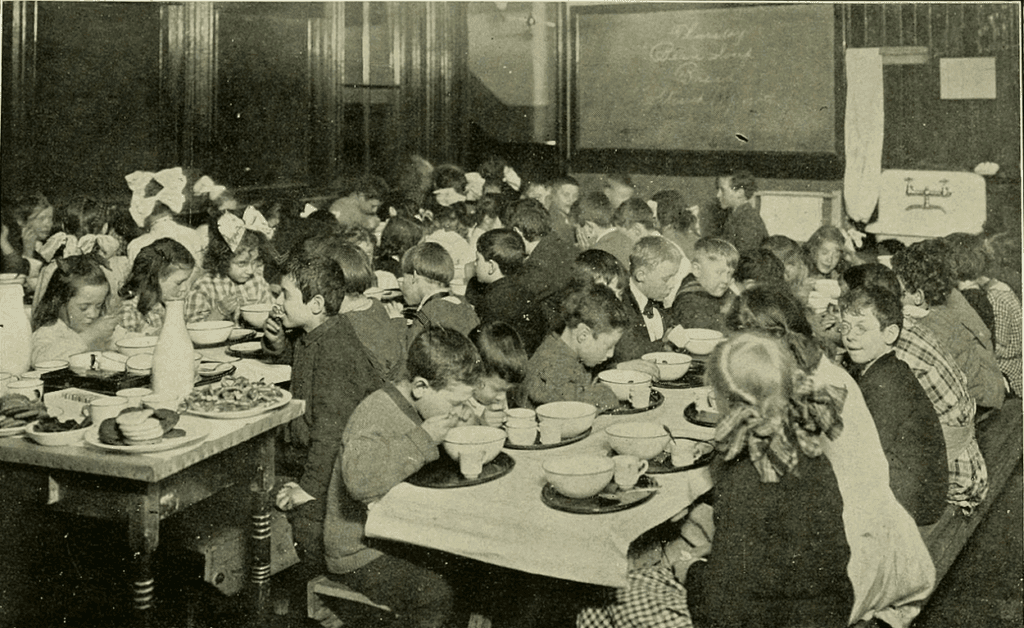

The social impact of school lunches was compelling. The story reflects broader societal changes, economic conditions, and evolving attitudes toward education and health. School lunches have been an integral part of the educational system for over a century, serving not only as nourishment but also as a tool for social equity. The single, most significant benefit of school lunch was measurable all-across the nation. Following the 1946 legislation that created the National School Lunch Program, some eight million American schoolchildren receive hot lunch at school each day.

The origin of school lunches dates to a time when most American children arrived at school on “school busses” like the one above, and in places like Boston, Massachusetts, where people like Ellen Richards, the founder of the home economics movement and the first woman admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, saw to providing lunch each day for over 5,000 Boston school kids for 2 to 6¢. The menu included black bean soup, ham sandwiches, buttered corn muffins, and baked beans.

By the early twentieth century (1916), the Woman’s Chautauqua Club of Kentucky campaigned for lunch programs in rural areas of their state. They had two menus: one featured cream of celery soup, two bread and butter sandwiches, and an orange or apple; the other menu started with a Cottage cheese sandwich, a four-ounce bowl of Creole soup, and two ginger cookies.

In 1919 a similar program was started in Indianapolis when a women’s club began offering a “morning lunch” for children who arrived at school without having breakfast. Many other programs such as the one in New York City were informal and provided by charitable organizations that supported children from impoverished families. Children received a snack of soup, crackers, milk, or hot chocolate. “Morning Lunch” was meant to tide the children over until noon. Teachers immediately saw better learning taking place in the classroom.

The idea gained momentum in the 1930s when during the Great Depression the federal government began to recognize the importance of proper nutrition for learning. This legislation marked a significant shift, making school lunches a federal responsibility, ensuring that children across the country could access nutritious meals during school hours.

Throughout the Cold War era, concerns over health and nutrition continued to influence public debate about school lunch programs. The focus expanded from merely providing calories to promoting balanced diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The 1970s saw efforts to improve the nutritional quality of meals amid rising awareness of childhood obesity and diet-related health issues. Then in the 1980s, school lunch programs became a platform for addressing social inequalities, but the debate sank to its lowest level when the Reagan administration’s Department of Agriculture targeted children from low-income families with the inane (No – stupid is the right word) argument that ketchup is a vegetable.

Thankfully, the suggestion met with public outcry and mockery, and the proposal was quickly reversed.

The social impact of school lunches extended beyond nutrition. They served as vital social equalizers, bringing together children from diverse backgrounds. For some children lunch at school was the only time they ever got to talk to kids with only one parent, or kids with handicaps or disabilities, or one that lived in a home without books or toys. School cafeterias often became spaces where students learned as much as they did in a classroom. Moreover, free or reduced-price lunch programs helped reduce food insecurity.

School cafeteria workers also influenced thousands. Vivid in my memory was an elderly lady we called Mrs. M-something. Twenty or more years later I learned that her name was Michaelowski. How many six-year-old kids could pronounce a name like that? We couldn’t say her name, but we loved the hugs we got from her and the gum-drop candies she carried in her apron pockets.

In recent decades and for generations to come, there has been and will be movement toward healthier school meal options, i.e., breakfast programs that close a widening gap between foods that can be purchased at reasonable prices. (Have you bought a box of Corn Flakes recently? At my neighborhood market a family size is $6.49.) Initiatives like breakfast programs go a long way toward making the whole school day productive – not just the after-lunch hours.

All this is not to say there isn’t work left to do. Despite progress, challenges remain. Funding needs to be increased to prevent disparities. Food waste needs to be controlled, and disparities (even within school districts) need correcting. Nonetheless, the history of school lunches helps us understand the vital role such programs play in America.

As for tomorrow or whenever the grandkids are around, forget telling them of the mile-long walks to school, uphill in the snow, tell them about the Cottage cheese sandwiches and celery soup.

Thank you for this article! In Yakima Washington. a dedicated teacher/principal at Jefferson Ele-

mentry Miss Ruth Childs saw the need during the l930ies and arranged for parents to bring in whatever they had

from gardens and with whatever money she could raise Miss Childs & parents cooked (hearty soups mostly) lunches so kids could have at least one solid meal a day. It was reported not to be unusual for her dresses to have holes in them from the sparks from the wood burning stove.