The World War I campaign to “Save the Wheat and Help the Fleet” emerged from a time when food, trans-Atlantic shipping, and national survival were tightly connected. Britain, like much of Europe, depended heavily on imported wheat, and German U‑boats were sinking merchant ships at an alarming rate – as many as 400 in some months.

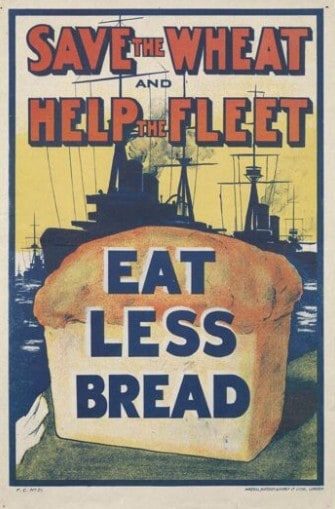

Posters such as the one produced by Hazell, Watson & Viney showing a massive loaf of bread perched on a cliff at Dover with the silhouettes of Royal Navy warships behind it, urged civilians to conserve wheat so that the fleet could continue receiving essential supplies. The message was simple but powerful: every slice of bread saved at home strengthened the nation’s ability to fight at sea.

The campaign grew out of a broader wartime food conservation movement. Britain imported boatloads of wheat from across its empire, mostly Canada, India, Australia, and from major grain regions like the United States and Argentina.

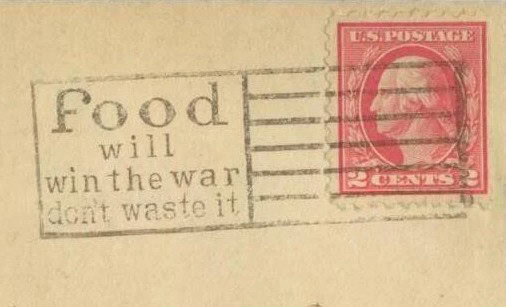

When German U‑boats began targeting transatlantic shipping in 1914, these lifelines were severely threatened. Wheat had become not just a dietary staple but a strategic resource. Posters and public messaging (postcards, too!) reframed everyday eating habits as acts of patriotism. Choosing to eat less bread meant freeing up wheat for the military and reducing the number of vulnerable supply ships that needed to cross the Atlantic.

The imagery of the “Save the Wheat and Help the Fleet” campaign made this connection visually explicit. The loaf of bread dominates the foreground, while the fleet, Britain’s shield against invasion, sits in the background, partially obscured but unmistakably present. The message suggested that conserving wheat at home directly supported the navy’s ability to protect shipping lanes and maintain Britain’s war effort.

The Royal Navy played a crucial role in escorting merchant vessels and keeping supply routes open. Without sufficient food imports, Britain risked both civilian hardship and military weakness. The campaign emphasized that the fleet’s protection of merchant convoys was essential for national survival. By linking wheat conservation to naval strength, the campaign encouraged civilians to see themselves as active participants in the war effort. An effort that even the King endorsed.

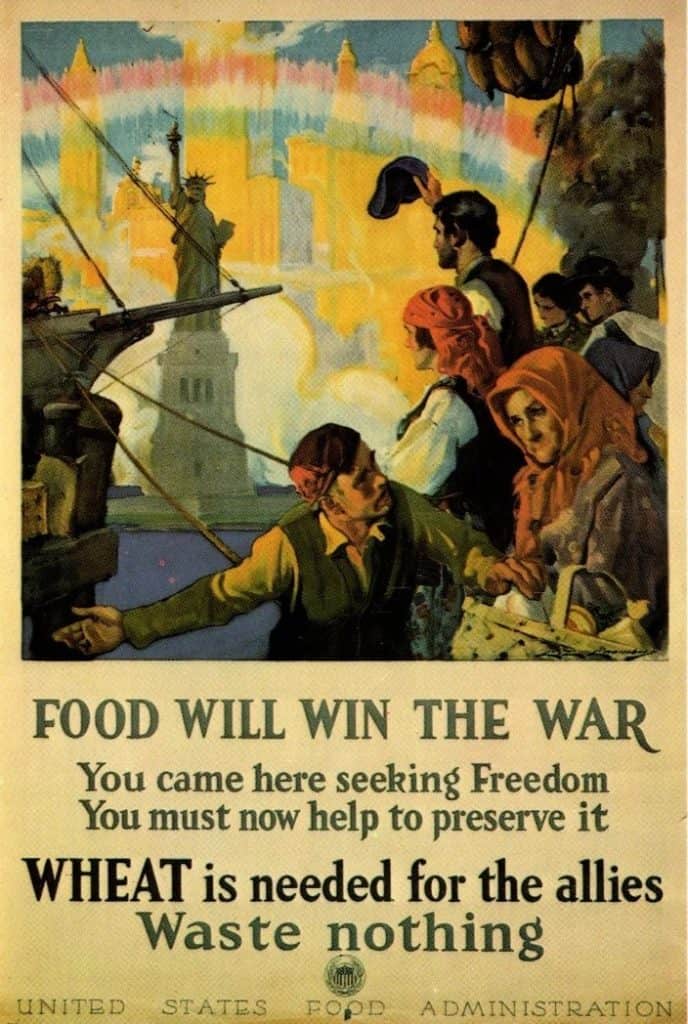

It was also part of a new and developing mindset in most Allied nations. The United States, for example, developed a Food Administration led by Herbert Hoover who promoted a campaign called, “Food Will Win the War.” The ideas for “Meatless Monday” and “Wheatless Wednesday” to conserve food weren’t quirky diet trends, they were a nationwide wartime mobilization strategy created to conserve food so the U.S. could feed both its troops and starving European civilians. The British campaign shared this spirit of voluntary sacrifice, relying on persuasion rather than rationing in the early years of the war.

Because bread was essential to the wartime diet, the shortage of wheat threatened morale as much as nutrition. Encouraging people to “eat less bread” was both practical and symbolic. It asked civilians to rethink their daily habits and recognize that even small acts like skipping a slice of toast could contribute to the national cause.

Ultimately, “Save the Wheat and Help the Fleet” was more than a conservation program. It made the British civilian aware that his sacrifice mattered and that the simple act of eating less bread could help safeguard his nation.

***

Here in America, Americans were still in the throes of isolationism, and “Meatless Monday” and “Wheatless Wednesday,” because they were part of a voluntary conservation campaign, seemed more palatable to Americans since we were asked—not forced—to save key staples for the war effort. The messaging even reached our postal cancels.

As “food czar,” Herbert Hoover’s popularity soared and his many enthusiasts promoted using substitutes like corn, barley, honey, and potatoes instead of wheat, meat, and sugar. Doing so was a unifying patriotic effort and a massive success. These voluntary measures helped double the amount of food shipped to Europe within a year and cut U.S. consumption by about 15%.

Such a reminder of the sacrifices our grandparents and great-grandparents went through during “The Great War”. I’d never seen any of the postcards or cancellation shown in the article. I’ll keep an eye out for them. Thank you!