Sadness touched Fredericksburg, Virginia, earlier than most communities at the start of World War II–two years before the USA was officially involved in the war. It was a fact starkly driven home to me when I stumbled upon the memorial stone to Robert Shenton Harris in the City Cemetery.

Robert Shenton Harris, whose father Robert ran a grocery store on William Street (where the Free Lance-Star now stands) and whose mother Susie Shenton Harris managed a household at 1308 Winchester Street, did what many students do when they graduate from college: he decided to take a trip before enrolling in graduate school at Cornell University.

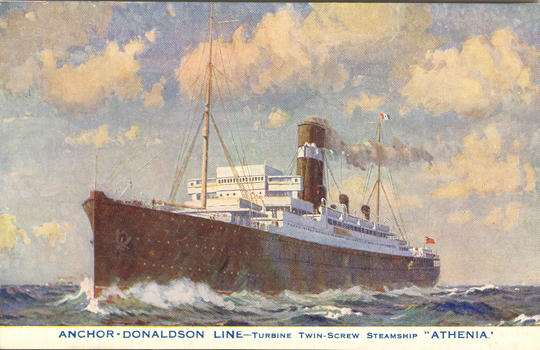

The summer of 1939, Harris and his friend Bill Buchannan of Danville set out for Europe–into a region aboil with unrest and talk of war. They started their tour on bikes, eventually switching to trains, taking up with locals, even at one point joining in a salute of Hitler (long before the world recognized the Hitler we know). But in August, Robert’s grandmother died, and his father cabled him asking him to return early. He did, booking passage on the S.S. Athenia, along with 1,103 other souls, departing Liverpool on September 3, 1939.

Two days before his departure, Germany invaded Poland. And just hours before Athenia pulled out of the docks at Liverpool, Great Britain declared war on Germany. That evening, 60 miles off the Irish coast, a German U-boat spotted Athenia. A single torpedo ripped into the passenger liner, and the doomed ship starting sinking by the stern.

Royal Navy vessels and merchant ships rushed to the scene. Most of the passengers were rescued, including Robert’s companion Bill Buchanan. But what happened to Robert Harris in the minutes and hours to follow is not known. Perhaps he died in the initial blast. More likely he died when one of the lifeboats was crushed in the propeller of one of the rescue ships. In any event, he was one of 117 who did not survive the disaster, one of 28 Americans. Robert Harris was among the first of more than 400,000 Americans who would die in World War II.

Robert’s sister, Anne Harris Skinner, told me the family heard on the radio that Athenia had been torpedoed (the ship did not sink until September 4), and they knew Robert was on board. A reporter from the Free Lance-Star visited the house, asking for news, seeking a photo. The family waited for news–hoping that a rescue ship had taken Robert to some as-yet unreported port. A week…two…three…and then it became obvious that he was lost. His body was never recovered.

The family declined offers for any sort of memorial service, though finally Robert’s parents agreed to place a memorial stone in the cemetery. Anne Harris Skinner, 16 at the time of her brother’s death, went on to become a USO girl in Fredericksburg during the war, providing company to visiting soldiers at the USO center on Canal Street–today the Dorothy Hart Community Center. Today she lives in California.

The memorial stone for Robert Shenton Harris is located near the front wall of the City Cemetery, about 100 feet to the left of the main gate on Amelia Street. His parents are buried next to him, and his grandmother–whose death prompted his change of plans–next to them. The Harris family was the first of dozens of Fredericksburg families that would suffer crushing sadness over the next six years.

My thanks to Anne Harris Skinner for sharing with me her memories.