The Perdicaris Kidnapping

This sad and grubby postcard was discovered in a 25¢ box at the Havre de Grace (MD) postcard show last August. It caught my attention because it looks like one of those ghoulish after-life photos that were once popular. With a little research, I found this story.

The Times (Trenton, NJ), by the Editors.

[Postcard History Note: This story is from an Advance Publications newspaper that has served New Jersey’s capital city since 1888. In a website entitled capitalcentury.com a rather worthy attempt has been made to select one hundred stories from the 20th century that helped define Trenton. The event here reported occurred in 1904.]

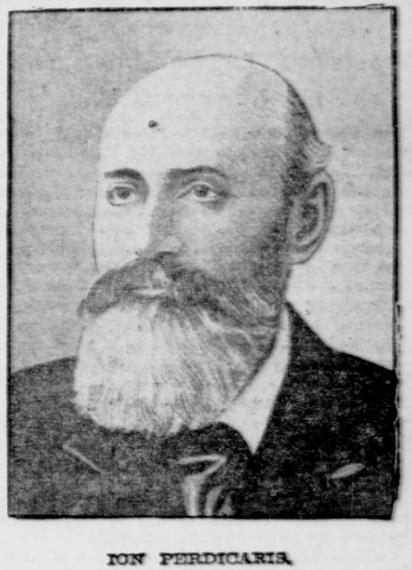

Long before there were suicide bombers, Osama bin Laden or chants of “Death to the Great Satan,” a Trenton man named Ion Perdicaris became the 20th century’s first American victim of Middle Eastern terrorism. It all happened in 1904, when the 64-year-old Perdicaris and his stepson found themselves taken hostage from their villa in Tangier, Morocco by a scruffy band of rifle-toting Berber tribesmen on horseback.

Their chieftain was the flamboyant, black-bearded Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli, and he wanted to extort a heavy ransom from the Sultan of Morocco. This was more than a simple kidnapping in a distant land. For President Theodore Roosevelt, it was an opportunity to start waving his “big stick.”

It also gave Roosevelt the chance to issue one of his more blood-curdling proclamations, a statement that helped ensure his re-election: “Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead!” Still, for all the bluster contained in that ringing phrase, Roosevelt concealed the secret that Perdicaris was no longer an American citizen.

The strange saga of Ion Hanford Perdicaris began in 1840, when he was born an American citizen in Greece, the son of Gregory Perdicaris.

The elder Perdicaris was an Athenian who had emigrated to the United States, married a wealthy young woman from South Carolina and headed back to his native land to serve as American consul. When Ion was six the family moved back to America and settled in Trenton. There, Gregory Perdicaris built a mansion at East State Street and North Clinton Avenue, published a short-lived newspaper, and turned his wife’s wealth into a fortune by creating the Trenton Gas Light Company. Young Ion Perdicaris grew up with few cares. He attended the prestigious Trenton Academy, and took a liking to art and literature. He even wrote a verse play, “Tent Life,” but it gathered no critical acclaim.

In 1862, Ion Perdicaris secretly returned Greece to renounce his American citizenship and be naturalized a Greek citizen. He made this rash move to prevent the Confederacy from confiscating his mother’s huge estate, but few even in his family knew about it. On a later trip abroad, Ion Perdicaris fell in love with the warm, breezy climes of Tangier and built his own house there, calling it “A Place of Nightingales” and filling it with a menagerie of dogs, monkeys and cranes.

Late in life, he married an English actress and became a fixture in the large diplomatic community in Morocco that also included another Trentonian — the American consul, Samuel R. Gummere.

Morocco was then the only independent country in North Africa, but the sultan, Mulia Abdul-Aziz, was a weak puppet who played with his collection of grand pianos while rival bands of warlords tore his country apart. In this chaotic environment, western diplomats banded together and lived apart from the natives. Like other diplomatic homes, the Perdicaris villa was outside the city walls where they thought themselves safe, but this carefree existence was shattered the evening of May 18, 1904. Perdicaris and his stepson, Cromwell Varley, were dining on their terrace when they heard shrieks coming from their servants’ quarters. As they ran to the scene of the commotion a gang of Berbers brazenly grabbed them, clubbed them with gunstocks, bound their arms and ordered the captive duo out of the house. Guns to their backs, curved daggers at their throats, they were ordered onto horses and driven off their property to a tent deep in the desert. There, they met with Raisuli.

Raisuli was notorious and known as the “Last of the Barbary Pirates,” but for his admirers, he was a Robin Hood in white robes. The raid on Perdicaris’ home was only his latest and boldest power play against the sultan. Raisuli issued a list of demands for the release of the hostages and waited for the world’s reply.

How did Perdicaris, this heir to privilege, react upon meeting the desert warrior Raisuli? Incredibly, the two hit it off. It may well have been the first known case of the Stockholm Syndrome. “I go so far as to say that I do not regret having been his prisoner for some time,” Perdicaris would later write. “He is not a bandit, not a murderer, but a patriot forced into acts of brigandage to save his native soil and his people from the yoke of tyranny.”

Roosevelt did not see it that way. He was, after all, the swinger of the big stick, and he wasn’t going to let an obscure tribe of Berbers get away with kidnapping an American.

“Preposterous,” said Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, John Hay, responding to the ransom demands. Seven battleships from the Atlantic fleet were dispatched to the Moroccan coast, but even with those crying for blood, Roosevelt knew he couldn’t send marines on a rescue mission in unknown territory. Then on June 1, he was faced with further trouble – a confidential message from the U.S. embassy in Greece arrived saying that Perdicaris was not, as widely believed, an American citizen.

From a fallback position, the United States quietly enlisted Britain and France to put pressure on the sultan and accept Raisuli’s demands, which he agreed to do. On June 21st, to cover his tracks, Hay – no doubt with some prodding from the commander-in-chief – issued a stirring telegram to Gummere in Tangier; it read: “THIS GOVERNMENT WANTS PERDICARIS ALIVE OR RAISULI DEAD.”

Read for the first time at the Republican national convention, the challenge turned a dull proceeding into a frenzy of excitement. A few days later, Perdicaris was free, Raisuli was richer and Roosevelt was nominated for another term.

“It is a bad business,” Hay wrote. “We must keep it excessively confidential.” And confidential it stayed. Not until 1933, long after all the players in the Perdicaris drama had died, would a historian uncover the truth in official documents.

Into his 70s, Perdicaris came back to Trenton from time to time and visited his substantial real estate holdings. Perdicaris Place, off West State Street, is named after him and his father. He died in London in 1925.

Excellent article and what a great card to find in a quarter box. Also interesting that one of Trenton’s streets are named for him and his father.

That is such a ringing phase, that has been listed in most the history books, so it is great to find out the ‘rest of the story.’ Thanks