Benjamin H. Trask

Oyster Culture on Chesapeake Bay

A century ago, the Chesapeake Bay was synonymous with oysters. Specifically, the species, Crassostrea virginica, found in abundance in Virginia and Maryland waters. After the 1880s, the number of oysters showed a decline but harvests still amounted to millions of bushels. Innovations such as refrigeration, steam-powered transportation, artificial ice production and canning helped to make oysters available to a national market. The following postcards, postal card and message card demonstrate how the oyster was infused in the bay’s economy and culture.

Hotels on the Bay The region’s hotels were well known for serving oysters. A 1912 menu from the Chamberlain Hotel started with “York River Oysters” and featured “Fried Spring Chicken,

The region’s hotels were well known for serving oysters. A 1912 menu from the Chamberlain Hotel started with “York River Oysters” and featured “Fried Spring Chicken,  Virginia Style” and boiled weakfish in oyster sauce. Opened in 1903, the Belvedere Hotel of Baltimore was equally well known for its oyster offerings. This card with its holiday good wishes was sent during the peak of the traditional oyster season. After breeding in the summer, the mollusks “fatten” up in the colder months.

Virginia Style” and boiled weakfish in oyster sauce. Opened in 1903, the Belvedere Hotel of Baltimore was equally well known for its oyster offerings. This card with its holiday good wishes was sent during the peak of the traditional oyster season. After breeding in the summer, the mollusks “fatten” up in the colder months.

Dining Out and Home Cooking

Cooking

Mary Randolph, a well-connected boardinghouse owner in Richmond, Virginia, offered numerous oyster recipes in The Virginia House-Wife (1824). Creamy oyster soup, oyster dressing and pie; baked, fried and pickled oysters, oyster catsup and oyster ice cream.

Travelers frequently mentioned the ubiquitous oyster. During his first trip to the United States in the 1840s, English author Charles Dickens observed in the nation’s capital, “oysters are procurable in every style.”

The southern tour of Appleton’s Hand-Book (1866) noted of Baltimore, “Restaurants are numerous, and generally well kept. The oysters of the Chesapeake and its tributaries have long been famous.” At the same time, Norfolk boasted of “a great market for wild fowl, oysters, poultry, and vegetables.”

Bay Steamers and Dining Eyre Crowe, secretary for the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, recalled his boat trip down the Potomac River to Richmond was accented with local flavor when a “lusty negro [sic] rang the bell announcing supper, consisting of oyster soup.” Overnight travel between Norfolk and Baltimore promised seafood dining and good company between the two port cities. The venerable Old Bay Line offered its famed à la carte dinner for a dollar. The feast featured seasonal delights such as Mobjack Bay oysters, duck, Norfolk spot and terrapin.

Eyre Crowe, secretary for the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, recalled his boat trip down the Potomac River to Richmond was accented with local flavor when a “lusty negro [sic] rang the bell announcing supper, consisting of oyster soup.” Overnight travel between Norfolk and Baltimore promised seafood dining and good company between the two port cities. The venerable Old Bay Line offered its famed à la carte dinner for a dollar. The feast featured seasonal delights such as Mobjack Bay oysters, duck, Norfolk spot and terrapin.

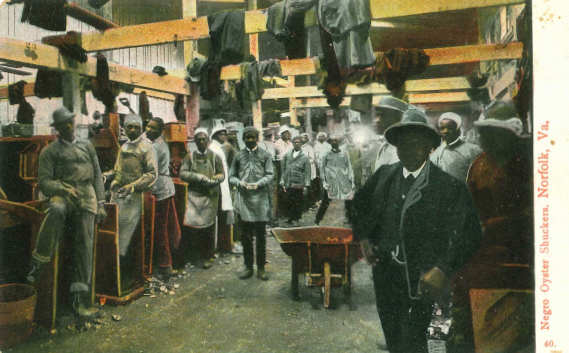

Oyster Trades In the monograph, The Great South (1875), journalist Edward King observed in Norfolk “barelegged negro boys sculling in the skiffs which they had half-filled with oysters and passed through streets entirely devoted to the establishments where the bivalve, torn from its shell, was packed in cans and stored to await his journey to the far West.” There were numerous affiliated trades with the oyster business. They included: shuckers, graders, canners, planters, oysterman, chandlers, boat builders and hucksters.

In the monograph, The Great South (1875), journalist Edward King observed in Norfolk “barelegged negro boys sculling in the skiffs which they had half-filled with oysters and passed through streets entirely devoted to the establishments where the bivalve, torn from its shell, was packed in cans and stored to await his journey to the far West.” There were numerous affiliated trades with the oyster business. They included: shuckers, graders, canners, planters, oysterman, chandlers, boat builders and hucksters.

After the Civil War, the oyster trades allowed African-Americans a path to economic independence through boat ownership. One of these entrepreneurs was John Mallory Phillips who used his earnings from his small fleet of boats to reinvest in other businesses and become a civic leader in Hampton, Virginia.

Feeding the demand beyond the Chesapeake Starting in the early 1800s, northeastern fisherman began to gather “seed” oysters in the Chesapeake Bay and replant them in home waters before harvesting. Both Virginia and Maryland passed laws to prevent this practice. For purists, however, there was no substitute for Chesapeake Bay oysters. The Lynnhaven oysters (off Virginia Beach) earned a Hollywood plug in the Universal motion picture, Diamond Jim (1935). James Buchanan Brady, the notorious gambler and epicurean, played by Edward Arnold, ordered a couple of dozen Lynnhaven oysters in a New York restaurant.

Starting in the early 1800s, northeastern fisherman began to gather “seed” oysters in the Chesapeake Bay and replant them in home waters before harvesting. Both Virginia and Maryland passed laws to prevent this practice. For purists, however, there was no substitute for Chesapeake Bay oysters. The Lynnhaven oysters (off Virginia Beach) earned a Hollywood plug in the Universal motion picture, Diamond Jim (1935). James Buchanan Brady, the notorious gambler and epicurean, played by Edward Arnold, ordered a couple of dozen Lynnhaven oysters in a New York restaurant.

Seafood dealers in Norfolk and Baltimore supplied customers across the country. In the 1870s, ads for Star Brand oysters of the William Ellis Company of Baltimore appeared throughout the Midwestern cities such as Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Omaha, Sioux City and Madison.

In 1901, when the North  American Oyster House and Restaurant opened in Chicago, it promised to “eclipse in beauty, spaciousness and completeness of appointments any restaurant in the country”.

American Oyster House and Restaurant opened in Chicago, it promised to “eclipse in beauty, spaciousness and completeness of appointments any restaurant in the country”.

Names and Landmarks A measure of the oyster’s economic importance can be found by examining place names. Communities of Oyster, Virginia and Bivalve, Maryland echo the business in shellfish. There is also an Oyster Creek in both states. Newport News has its midtown at Oyster Point.

A measure of the oyster’s economic importance can be found by examining place names. Communities of Oyster, Virginia and Bivalve, Maryland echo the business in shellfish. There is also an Oyster Creek in both states. Newport News has its midtown at Oyster Point.

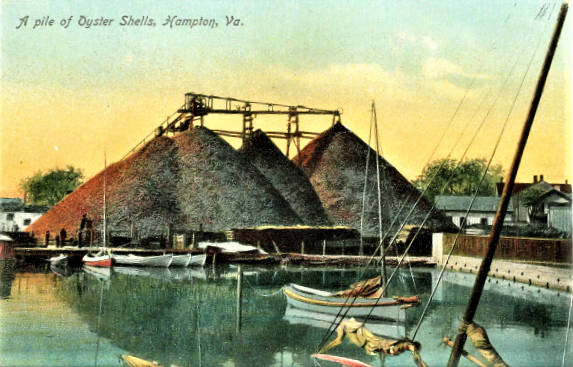

However, it was Frank Darling who built the most notable tribute to oysters on the Hampton River in Virginia. This navigation mark dominated the riverfront, a massive pile of shells. The subject of numerous postcards, one caption exclaimed: “200,000 BUSHELS OF OYSTER SHELLS, HAMPTON, VA.” This huge mountain of oyster shells adjoins one of the large oyster packing plants. It forms an object of interest to all tourists.

Related Uses

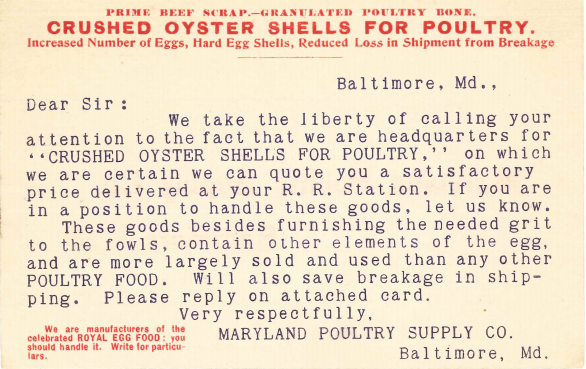

Having consum ed the succulent oysters, what to do with the millions of shells? The Powhatan Indians fashioned shells into arrowheads, tools, and utensils and added it as temper in pottery. In the early 1600s, Jamestown colonists applied oyster shell powder pigment to interior whitewash. Likewise, mortar that included shells was called “tabby.” Pharmacists added pulverized oyster chalk as the active ingredient in antacids. Shells became the aggregate for walkways and byways. This reply postal card from the Maryland Poultry Supply Company to the Minier Brothers of Big Flats, New York, promised the calcium-rich, crushed shells for fowl offered needed grit and resulted in harder egg shells.

ed the succulent oysters, what to do with the millions of shells? The Powhatan Indians fashioned shells into arrowheads, tools, and utensils and added it as temper in pottery. In the early 1600s, Jamestown colonists applied oyster shell powder pigment to interior whitewash. Likewise, mortar that included shells was called “tabby.” Pharmacists added pulverized oyster chalk as the active ingredient in antacids. Shells became the aggregate for walkways and byways. This reply postal card from the Maryland Poultry Supply Company to the Minier Brothers of Big Flats, New York, promised the calcium-rich, crushed shells for fowl offered needed grit and resulted in harder egg shells.

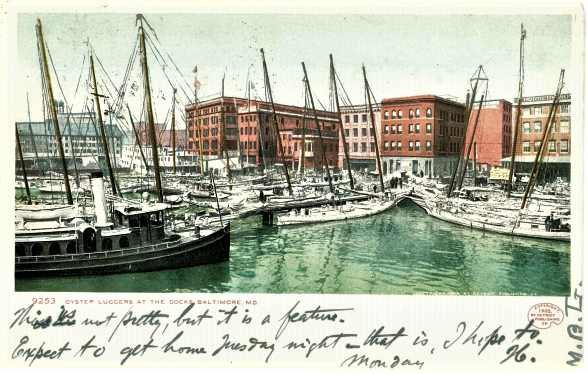

Bay Craft and the Oyster Industry The caption on this card refers to these vessels as “luggers.” However, they appear to be bugeyes and skipjacks. The later featured massive sails that dragged the oyster dredges across the beds. The Maryland skipjacks is the official boat of the state and the last, sail-powered workboats in the United States. The Chesapeake College of Wye Mills, Maryland adopted the mascot of “Skipjacks.” The school fighting spirit is personified by Cap’n Jack, clad in blue and green pirate garb. Other bay craft associated with the trade include buyboats, log canoes, deadrises, flatties, skiffs, and pungys.

The caption on this card refers to these vessels as “luggers.” However, they appear to be bugeyes and skipjacks. The later featured massive sails that dragged the oyster dredges across the beds. The Maryland skipjacks is the official boat of the state and the last, sail-powered workboats in the United States. The Chesapeake College of Wye Mills, Maryland adopted the mascot of “Skipjacks.” The school fighting spirit is personified by Cap’n Jack, clad in blue and green pirate garb. Other bay craft associated with the trade include buyboats, log canoes, deadrises, flatties, skiffs, and pungys.

Today’s Oysters and Chesapeake Culture

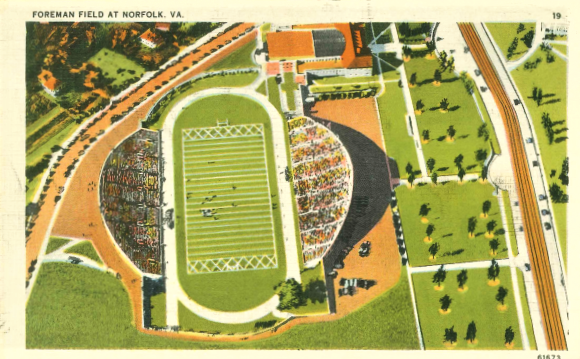

Despite the decline in the bay’s seafood industry in the mid-twentieth century, efforts continued to support this facet of the economy. One of those promotional events was the Shriner’s Oyster Bowl in Norfolk at Foreman Field. The fund-raiser started in 1946, as a high school football game before becoming a collegiate-level contest. Noteworthy, was the clash in 1963, which featured Heisman Trophy winner, Roger Staubach, quarterback of the United States Naval Academy, playing against the Virginia Military Institute. The game is still contested at the same location at the now-named S. B. Ballard Stadium.

Starting in 2014, the commonwealth of Virginia established the Oyster Trail. The initiative is part of the Renaissance of the bay’s oyster foodways. The effort blends interest in aquaculture, outdoor adventure, watermen’s culture, wineries, and fine dining. The trek takes travelers off the beaten-path to Old Dominion communities such as Urbanna, Poquoson, Machipongo and Onancock.

Since I attended college in the Norfolk-Virginia Beach area and am a seafood lover, this article was of great interest to me.

Glad you liked it.

Excellent article about the Chesapeake oyster industry. A lot of good historical info…

Concerted efforts are made in the preparation of every article in Postcard History. We strive to be as near perfect as possible. There is a spelling error in this piece that I missed or that Microsoft’s Auto Correct Spell Check created. The organization mentioned as sponsors of the football event is not Shiners, but Shriners. Apologies to all, Your Editor.

Anyone can swap postcard on Chesapeake Bay?