Editor’s Staff

The Ballad of Sally Brown

by Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood

You memorized some Keats and Shelley.

And, you’ve heard of Yeats and more.

Surely you read old Bill the Bard and decoded his sonnets, too.

About Rudyard Kipling, you know his Knighthood he declined.

For Brendan Behan no one knows if sober he ever was, but for all you know of this awesome lot, there is one you do not know. It’s safe for you may say, if you may or could, that you have never heard of Thomas Hood.

This is the true story of Faithless Sally Brown.

It’s been told by no one, for no one ever would, except perhaps by hapless Thomas Hood.

Thomas Hood, the younger, was born at the bitter end of the 18th century, to Thomas Hood, the elder, a bookseller in the oldest ward of Londontown. Thomas was well educated but was unsuited for most other things. He married but his wife was a shrew and snob; she even picked fights with the neighborhood fish sellers. Thomas was fond of practical jokes, but he stopped laughing when he was forced to work. He tried to write but everyone ignored him. Late in life he had some success with word-play poetry. The story of Ben and Sally Brown is among his best.

Faithless Sally Brown

Young Ben he was a nice young man,

A carpenter by trade;

And he fell in love with Sally Brown,

That was a lady’s maid.

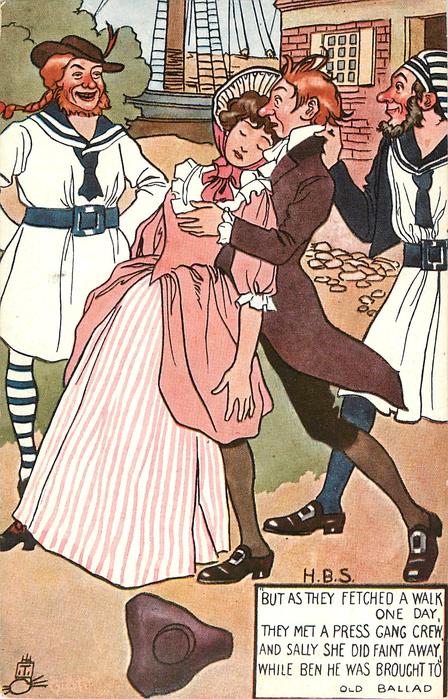

But as they fetch’d a walk one day,

They met a press-gang crew;

And Sally she did faint away,

Whilst Ben he was brought to.

The Boatswain swore with wicked words,

Enough to shock a saint.

That though she did seem in a fit,

‘Twas nothing but a feint.

“Come, girl,” said he, “hold up your head,

He’ll be as good as me;

For when your swain is in our boat,

A boatswain he will be.”

So when they’d made their game of her,

And taken off her elf,

She roused, and found she only was

A coming to herself.

“And is he gone, and is he gone?”

She cried, and wept outright:

“Then I will to the water-side,

And see him out of sight.”

A waterman came up to her, –

“Now, young woman,” said he,

“If you weep on so, you will make

Eye-water in the sea.”

“Alas! they’ve taken my beau, Ben,

To sail with old Benbow”;

And her woe began to run afresh,

As if she’d said Gee woe!

Says he, “They’ve only taken him

To the Tender-ship, you see”; –

“The Tender-ship,” cried Sally Brown,

What a hard-ship that must be!

“O! would I were a mermaid now,

For then I’d follow him;

But, oh! I’m not a fish-woman,

And so I cannot swim.

“Alas! I was not born beneath

‘The virgin and the scales,’

So I must curse my cruel stars,

And walk about in Wales,”

Now Ben had sail’d to many a place

That’s underneath the world;

But in two years the ship came home,

And all the sails were furl’d.

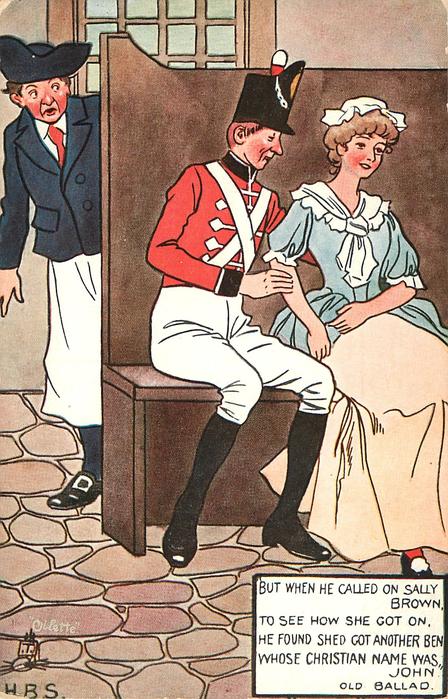

But when he call’d on Sally Brown,

To see how she went on,

He found she’d got another Ben,

Whose Christian name was John.

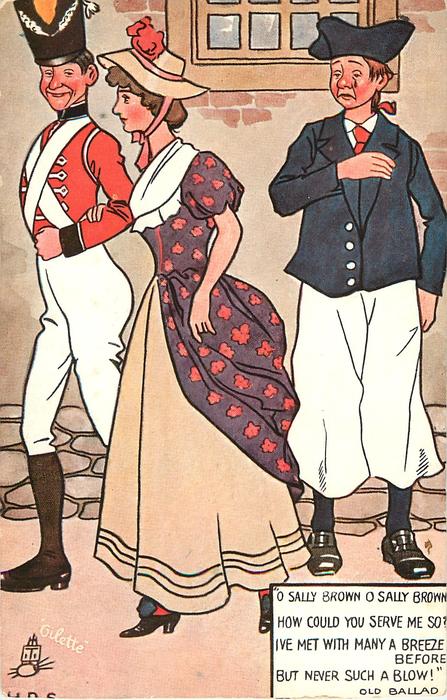

“O Sally Brown, O Sally Brown,

How could you serve me so,

I’ve met with many a breeze before,

But never such a blow!”

Then reading on his ‘bacco box,

He heaved a heavy sigh,

And then began to eye his pipe,

And then to pipe his eye.

And then he tried to sing “All’s Well,”

But could not, though he tried;

His head was turn’d, and so he chew’d

His pigtail till he died.

His death, which happen’d in his berth,

At forty-odd befell:

They went and told the sexton, and

The sexton toll’d the bell.

The illustrations are Tuck postcards series #9027. The series first appeared in 1908 under the title, Old England, then again in 1911 with the new title Sally Brown. ‘Eye, my fellow carders, so goes the story of Faithless Sally Brown.

The artist H.B.S. has remained unidentified at the end of several attempts to discover his/her name. The most inclusive search yet, has been the data base of over 16,800 artists who at one time or another was active in the United Kingdom. That search found Hugh Bellingham Smith, the only artist working during the Tuck era with those exact initials.

If anyone reading this has an inkling to do a search and should discover the identity of H.B.S., the Postcard History editor would appreciate knowing of your success.

I didn’t recognize the name Thomas Hood, but some of the wordplay in the poem is familiar, such as “They went and told the sexton, and/ The sexton toll’d the bell.”

I’d wanted to use an excerpt in a puzzle book, but then read the whole poem. Am I the only one who reads this to mean that she was badly harmed by the press gang? Or are the few comments I’ve found so far from folks turning a blind eye to the actual horror of this poem? Perhaps I’m misunderstanding something, but I definitely read it that way…that they hurt her badly and she turned to a bad lifestyle…to say it without saying it. There are definitely terms I don’t know, but I think it seems clear. What’s really upsetting… Read more »