Editor’s Staff

Portrait of an American City

Asheville, North Carolina

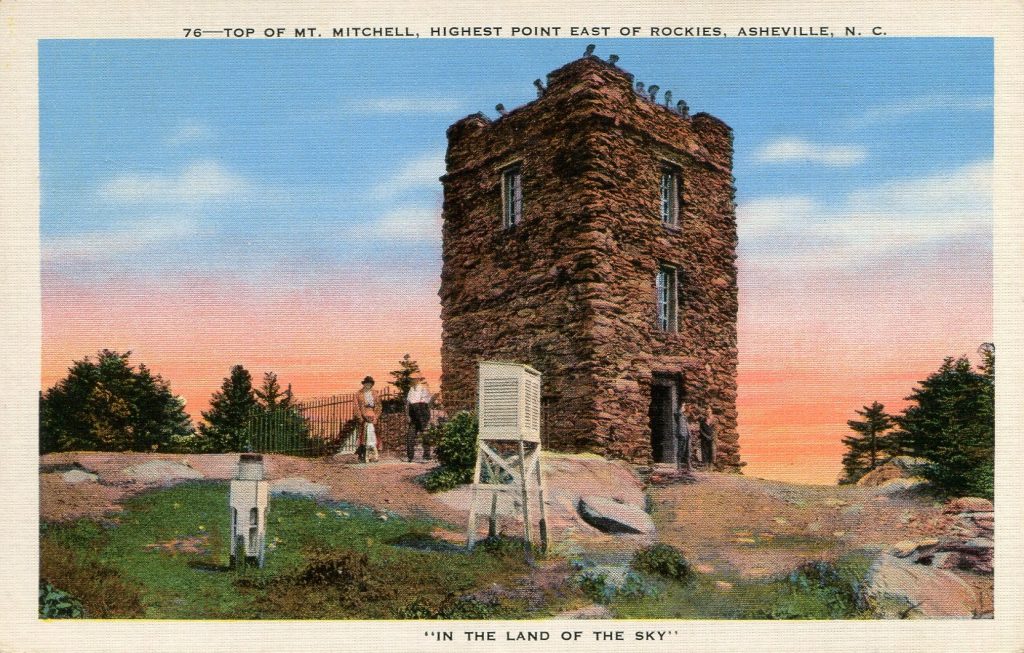

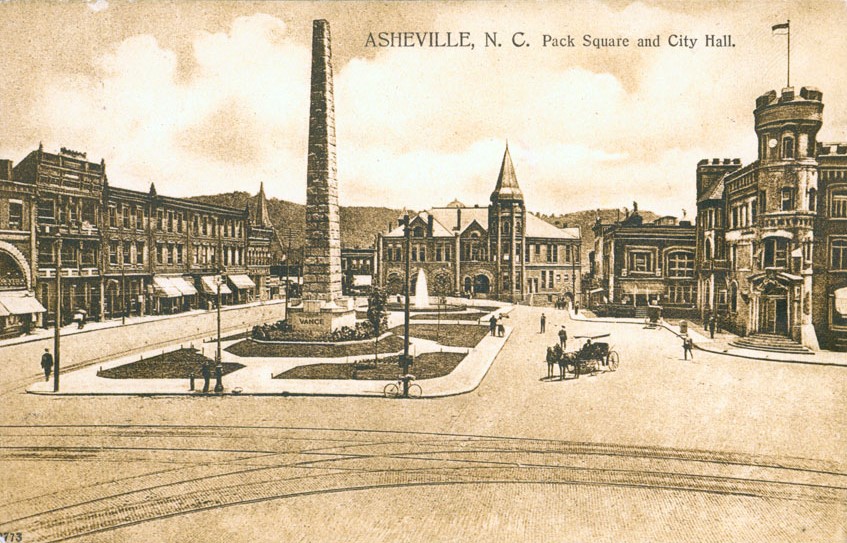

Postcard History invites you to a postcard portrait of Asheville, North Carolina. The city is best known for being the home of the Vanderbilt Mansion and its native son, the major American novelist Thomas Wolfe. With a population of nearly 100 thousand people, the city sits amid the Black Mountains. It is only 17 miles south of Mount Mitchell. The area is known as “The Land of the Sky,” the highest point in North America east of the Mississippi River.

The first Europeans settlers went to the area around 1784. Growth was fast and steady and by 1797 Asheville was incorporated. That was the same year that John Adams was sworn into office as the second president of the United States.

The next best thing to time-travel is history and postcards are the only tickets still for sale. This essay will examine only bits of Asheville’s history; those pieces that are illustrated by postcards found in a recent collection, and, we will include a piece of the city’s “lost history.”

Ashville’s most famous resident . . .

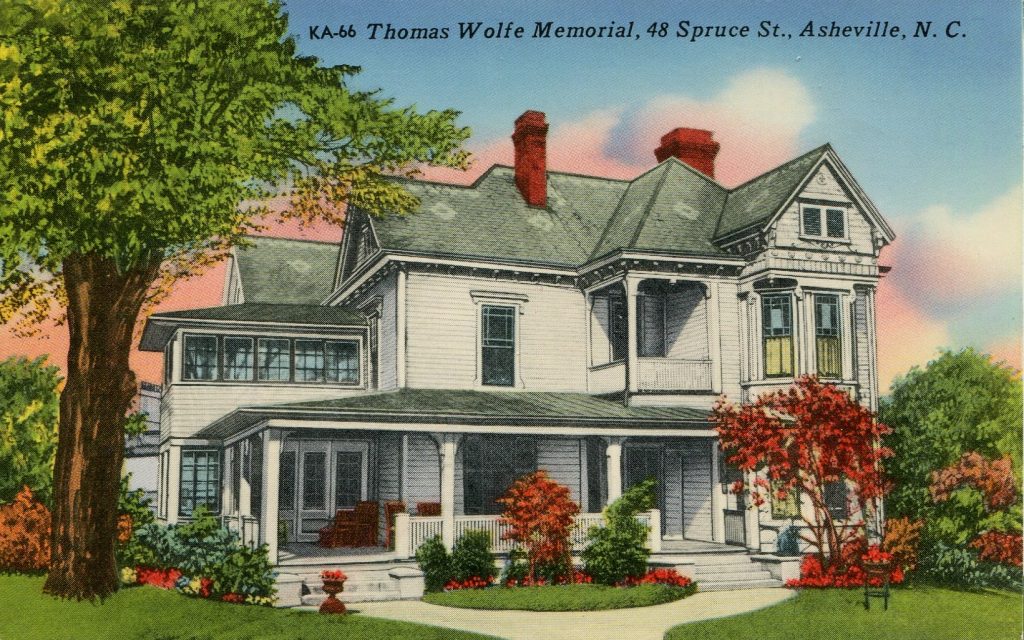

Large samples of twentieth century American literature came out of Asheville, and the credit goes mostly to one man – Thomas Wolfe. Wolfe, the author of Look Homeward Angel was a life-long resident and just after his death one contemporary, William Faulkner said that Wolfe may have been the greatest talent of their generation. Wolfe’s influence reached Jack Kerouac, Ray Bradbury, and Philip Roth. He is considered the first master of autobiographical fiction. Other well-known works include Of Time and the River, You Can’t Go Home Again, and The Web and the Rock.

Thomas Wolfe’s Home in Asheville

The house in the novel, Look Homeward Angel (1929) was the home of the Gants; a fictionalized family based on Thomas Wolfe’s own. The house is known to many American readers as “Dixieland,” the boarding house operated by Eliza Gant. It is now restored as it was during Wolfe’s teen years.

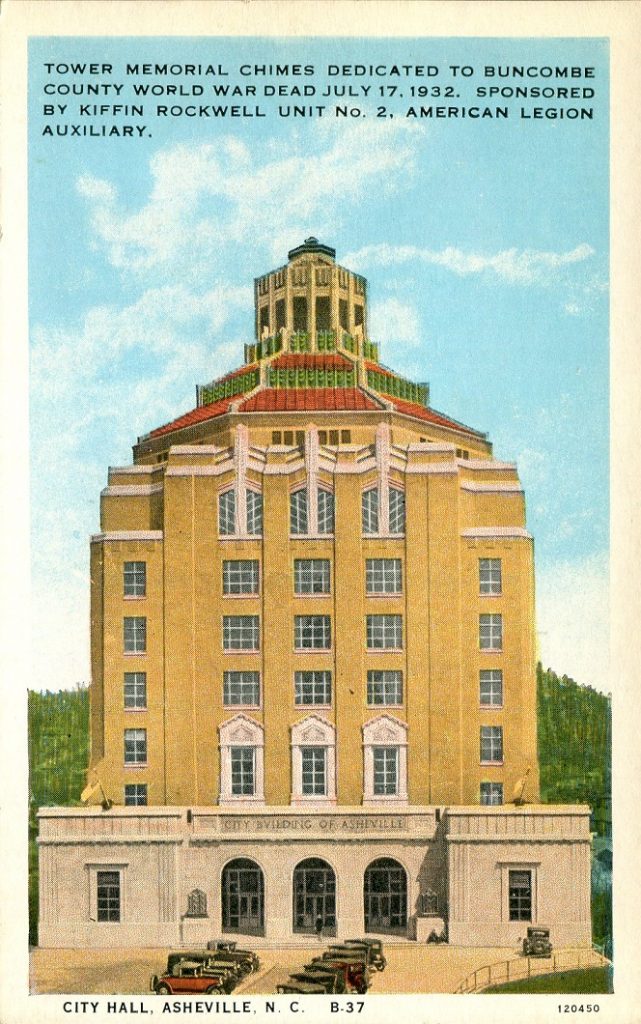

Public Places

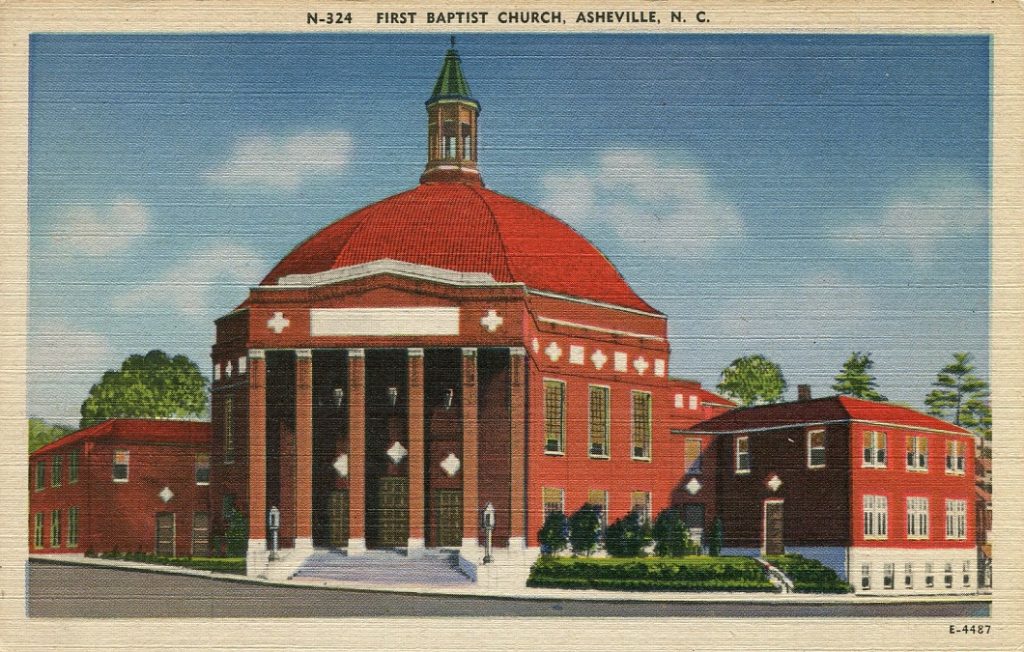

The Asheville City Hall was built by the Asheville architect Douglas Dobell Ellington. He first gained notoriety while still enrolled at the Drexel Institute of Philadelphia, then at the University of Pennsylvania, and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. One interesting turn in Ellington’s career was during World War II when he worked with the United States Navy in attempts to design camouflage for destroyers, cruisers, and battleships. Other of Ellington’s buildings in Asheville are the First Baptist Church and the Asheville High School.

The Asheville City Hall is dedicated to the dead from World War II.

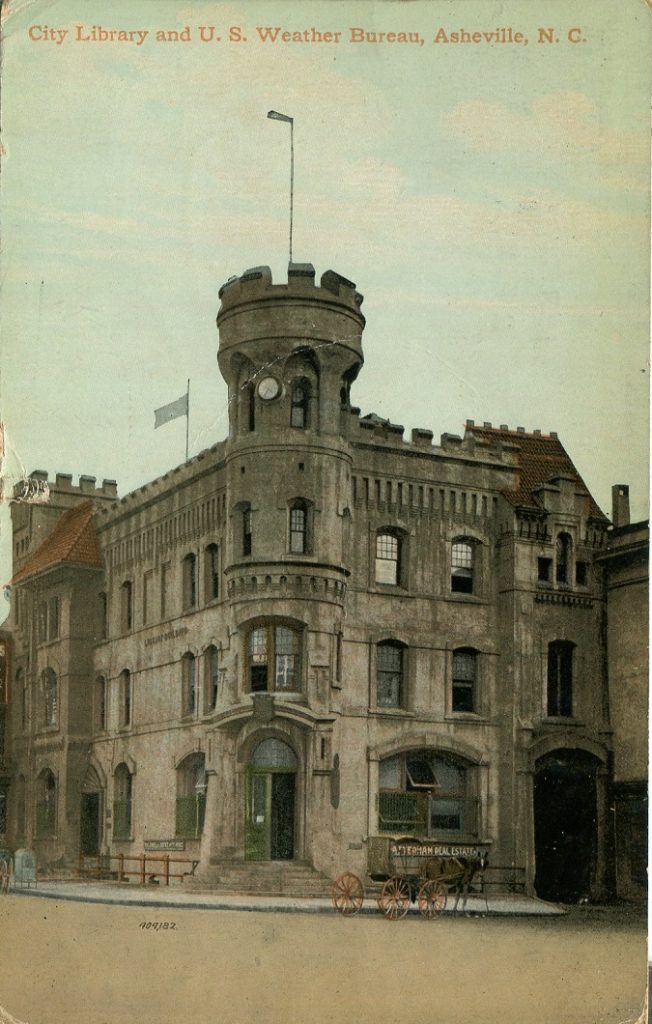

The other card above has a caption that reads City Library and U. S. Weather Bureau, Asheville, N. C. It was about to stand alone as a curious bit of history, until a phone call was placed to the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County, North Carolina.

The knowledgeable executive director took my call and researched the history of this curious building in less than an hour.

Built in 1887 and first known as the First National Bank building, it was purchased by George W. Pack a decade later and became the Palmetto Building in January 1898. Pack donated the Palmetto Building in February 1899 to the city for a library. After that it was called the Asheville Library and was under the direction of a library association. Its address – taken from a 1909 city directory – was South Pack Square.

The image below was submitted to Postcard History as an example of its relative location.

While being used by the library association, the upper floors housed law offices and the weather bureau from about 1908 until July 1910. The building was demolished in 1925.

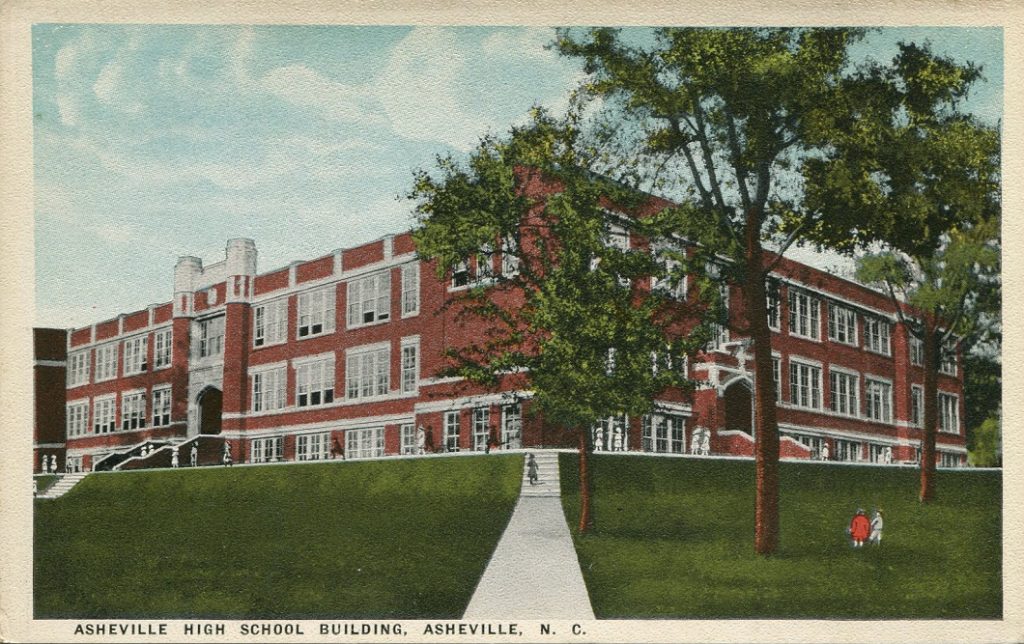

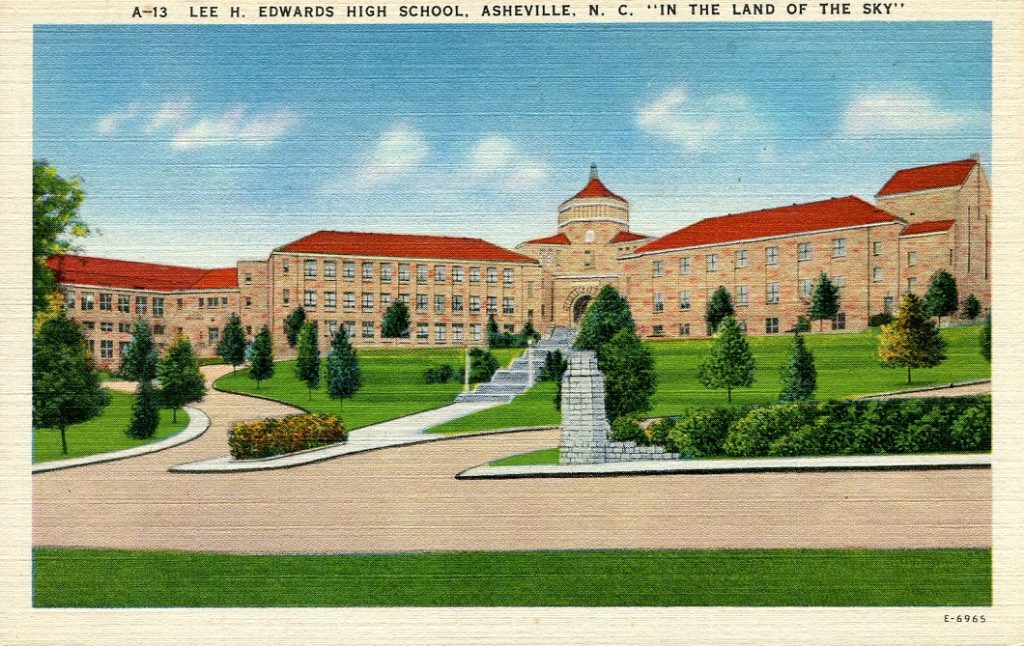

Schools

The railroads reached Asheville in the 1880s and the population exploded. Within the decade it was decided that the city needed a public school system. The initial investment included a high school at the corner of Broadway and Woodfin Streets and three elementary schools.

In 1927, as mentioned above, local architect D. D. Ellington prepared a design for a new high school to be built on a piece of public parkland off McDowell Street. The school opened in February 1929 with a wide range of vocational programs, but with an equal number of scholastic ones.

The school was renamed in 1935 as the Lee H. Edwards High School to honor the principal who died unexpectedly that year. In 1969, the name reverted to Asheville High School.

Churches

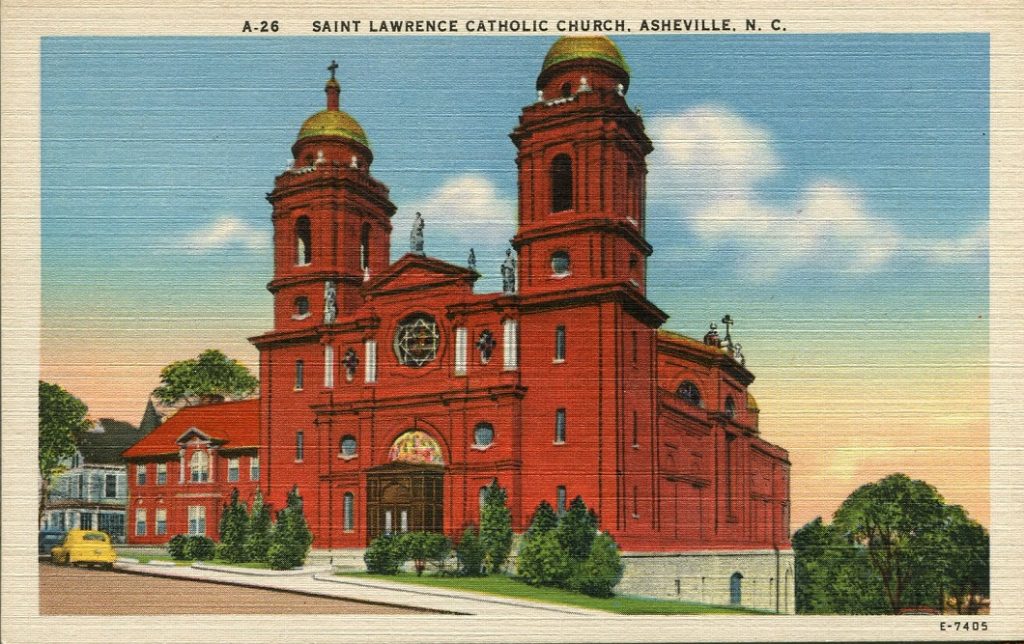

The churches in Asheville represent all denominations. Two of the most distinctive are the First Baptist Church and the Roman Catholic Minor Bascilica of Saint Lawrence.

The Baptist church is another of Douglas Ellington’s creations.

Saint Lawrence Catholic church was built in 1905. The design is in his native style by Spanish architect Rafael Guastavino. Guastavino came to America in 1881 from his home in Valencia and spent the next three decades in New York City. His specialty was fire-proof construction. The designation of minor bascilica was granted by Pope John Paul II in 1993.

Lost Ashville

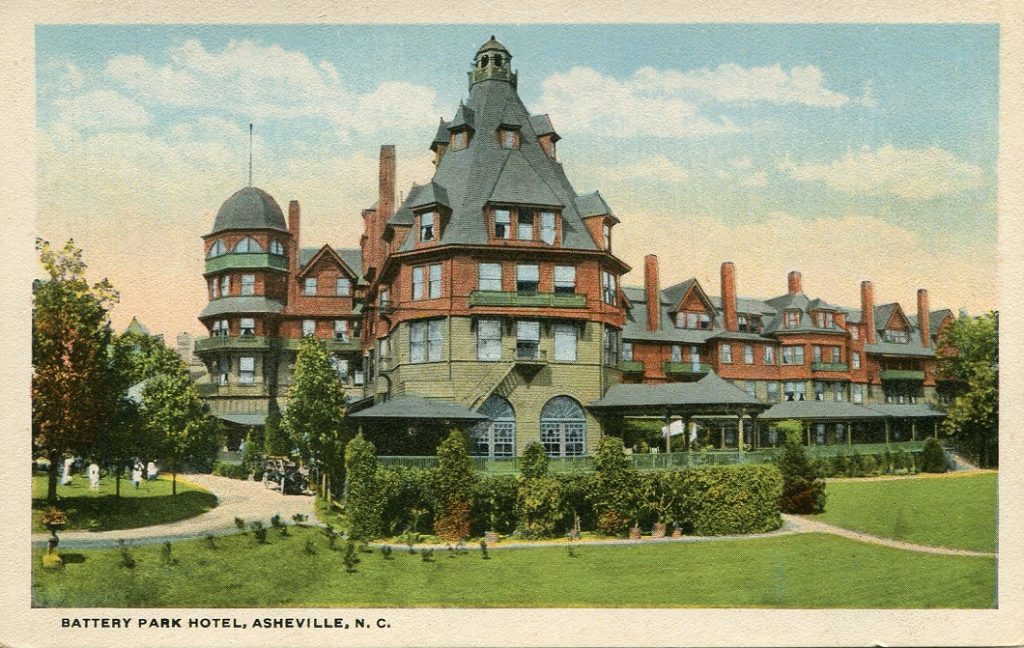

The construction of the original, stately, Battery Park Hotel on a resort style campus, was completed in the summer of 1886. It was built by Colonel Frank Coxe, the title was honorary, the sire of the Coxe family in North Carolina. In the last decades of the 18th century, the Coxe family settled in New Jersey, made their money in Pennsylvania, and moved to North Carolina.

Frank Coxe was educated at the University of Pennsylvania where he earned a degree in engineering and worked until the outbreak of the Civil War in the mines that belonged to his family. He later served (but only for a short time) in Joseph Kershaw’s Brigade of South Carolina Volunteers. His service was shortened because the Union threatened the confiscation of the family’s property in Pennsylvania if he continued to serve the Confederacy. Coxe’s industrial interest in the Asheville area resulted in great wealth and the Battery Park Hotel opened July 12, 1886 as a place to accommodate Coxe Family business interests.

The hotel most likely employed one of America’s first marketing geniuses. From January 1889 the names of the “multimillionaires” who were guests at the Battery Park Hotel that week were published in the Asheville Citizen. The guests loved seeing their names in the paper and business grew steadily for the next three decades. And, like so many other hospitality enterprises of the era, the Battery Park went the way of the Jazz Age, when automobile tourism outpaced the railroads.

Trivia update: The Battery Park Hotel was the first hotel in the south with an electric elevator.

I knew nothing about Asheville, North Carolina. Pleased to read about it. Thank you.

Thanks for opening my eyes to the many items I have missed when visiting Asheville. Lots more to see on our next trip!

I wondered why Asheville High School reverted to its old name after honoring Edwards for over three decades, and learned it was as a result of racial integration.

Great postcards, and they bring back fond memories of a visit to Asheville. Mount Mitchell no longer has that great old stone tower, but is well worth a visit with a good viewing platform, museum, visitor center, restaurant, and trails to surrounding peaks. The Thomas Wolfe house is still there and open for tours, and would be of interest to anyone interested in historical homes or literature.