Nathaniel Dancer

The Big Five

Part Two

Last Monday we looked at the first two concert halls in America and the orchestras that used them. We spoke of music being the language of the angels. Today we again look to the angels to guide us through the histories of halls and orchestras in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Cleveland. With such, this essay on “The Big Five” is complete.

Orchestra Hall, Michigan Avenue, Chicago

For nearly a century, Orchestra Hall was the primary performance center for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Those responsible for the initial construction project chose Daniel Burnham as the architect, he had just come-off a rather significate project, being that of the White City, the colloquial name for the Chicago World’s Fair.

By the end of the 20th century an idea for new concert hall was under consideration, but tradition and cost factors proved that renovation was the path to follow. The project called for an extensive list of improvements but foremost were the strengthening of the foundation and the expansion of rehearsal halls, lobbies, meeting rooms, and a public arcade that connects the Michigan Avenue Symphony Center entrance to a new rotunda.

Orchestra halls around the world are renowned for two reasons: acoustics and décor. For the musicians, the acoustic properties are paramount, but the audience is most enamored with the décor. One feature at Orchestra Hall that is unique is its white stage, unlike any place in the world. Chicagoans love it!

Today, Orchestra Hall remains the home of the CSO and with the expanded facility it appears that the hall will service the orchestra for another century.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Theodore Thomas first appeared in 1891. Through the years, Orchestra Hall has been their home and primary performance venue, but in the summer months, since 1905, when the concerts move outside, the CSO travels to the Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, Illinois. The Ravinia Festival is the oldest outdoor venue in the United States.

The Chicago Symphony has amassed an extensive discography. Recordings by the CSO have earned 63 Grammy Awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Beginning in May 1916, Frederick Stock and the orchestra recorded the Wedding March from Felix Mendelssohn’s

A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Columbia Records. The CSO’s numerous recordings for Columbia and RCA Victor were some of the first (1925) electric recordings made.

The tradition of recordings continued after Stock’s death in 1942, with Rafael Kubelík, and many of the world’s foremost conductors: including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Georg Solti, and Riccardo Muti.

* * *

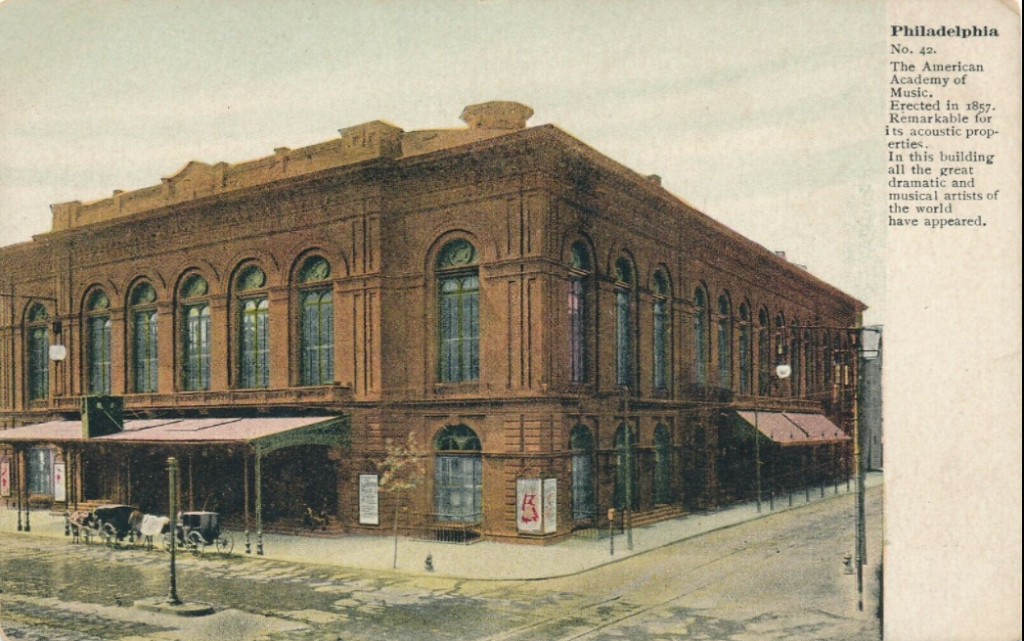

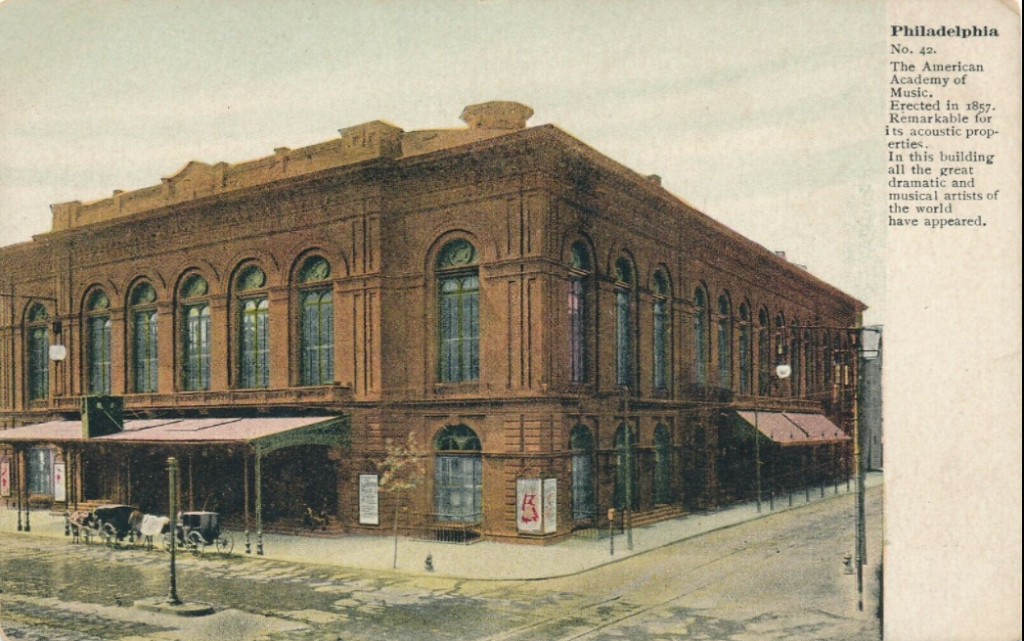

The Academy of Music, South Broad Street, Philadelphia

The Academy of Music is a hall for which this writer has a grand respect. It was the site of the first concert I attended in the United States on January 27, 1967. The Vienna Philharmonic was on tour and maestro Josef Krips conducted the overture to Wagner’s

Flying Dutchman, a Mozart piano concerto, and Brahms’s Third Symphony.

[Aside: I want to tell you about one of the most bazaar coincidences of my life. Fifty years later, in a discussion with Postcard History’s editor, we looked at each other in complete astonishments and realized that we could have met all those years ago. Ray was at the Academy that night with his wife and his parents celebrating his father’s birthday. What a small world it is!]

The Academy was built in 1855 as an opera house. On many occasions each year, opera is still sung at the Academy, making it the oldest building in the United States still in use for its original purpose. Philadelphians call the Academy, the “Grand Old Lady of Locust Street.” (This is indeed a mystery to me since the entrance is on Broad Street.)

In other than arts performances the building hosted the 1872 Republican National Convention where Ulysses S. Grant accepted the nomination for his second term as President. It has been used as a movie set and the site of hundreds of school and university graduations.

Today the Academy is the home of the Pennsylvania Ballet, Opera Philadelphia, and for one-hundred and one years it was the home of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphians played first on November 16, 1900 under the baton of Fritz Scheel.

Early in the orchestra’s history (1912) a young British conductor with a Polish name was hired to be the third conductor – Leopold Stokowski. His first appearance with the orchestra took place on October 11, 1912. (10/11/12 – the numerologists went crazy!)

Everyone loved Leopold! Even Micky Mouse loved Maestro Stokowski for it was Leopold Stokowski with whom Mickey shared the starring role in the movie,

Fantasia, produced by the Walt Disney Studios in the fall of 1940.

Stokowski’s contract in Philadelphia was extended year after year and in the end he conducted there for twenty-six years. That was somewhat of a record, at least until the Philadelphians hired their fourth conductor – Eugene Ormandy. Dr. Ormandy became a second long-term music director; his forty-four year tenure became the longest serving conductorship in American music history.

In years gone by the Philadelphians enjoyed a reputation based on a certain something called the Philadelphia Sound. It was a nearly indefinable characteristic of performance that was often described as soft strings, clarion brass and luscious woodwinds. Ask any Philadelphian who attended a concert in the seventy years between 1912 and 1982. They’ll tell you all about it.

* * *

Severance Hall, Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio

Adelia Prentiss Hughes, a native of Cleveland had worked for the better part of the 1920s in her quest to create a world-class civic orchestra for the city of her birth. For the most part, she enjoyed grand success with several musical achievements to her credit, but by the end of the decade, Hughes had devoted herself to the construction of a permanent home for the Orchestra. Since the founding of the orchestra in the previous decade they performed in no less than three different locales.

In 1926 campaigning for funds, both public or private was a popular cause with high public interest, but the interest generated very little response. Then like a bolt of lightning at a concert in 1928 John L. Severance and his wife Elizabeth went to the stage unannounced and pledged one-million dollars toward a new Cleveland Orchestra Concert Hall.

The first gala concert occurred on February 4, 1931. In the weeks and months that followed, news of some very surprising features of Cleveland’s new “Palace of Music” were revealed. One such feature was, according to the wire-services for several area newspapers, the in-house radio station. The station, designed specifically to broadcast classical music, thrilled music lovers across the country. During the March that followed, it was announced that the funds needed to complete the payments on the hall had been raised due to high ticket sales and tens-of-thousands in additional donations by the public. The final cost: $2,500,000.

The Cleveland Orchestra is the youngest of the “Big Five.” Founded in 1918 by a pianist who enjoyed an international reputation, Adelia Prentiss Hughes. Born in Cleveland at the end of the Civil War, Miss Hughes attended and graduated from Vassar College with a degree in music. While at college Adelia sang in the glee club choir with a sister-student named Elizabeth Rockefeller, who just happened to be the oldest daughter of a man name John D. Rockefeller. That connection proved to be invaluable in the years ahead.

Miss Hughes’s personal history would fill volumes in the book of musical achievements, one of which was the first ever recording in 1924 of Tchaikovsky’s

The Year 1812 Solemn Overture.

Conductors at Cleveland enjoyed five long-term periods of glorious success beginning with a Russian born conductor/composer name Nikolai Sokoloff. Sokoloff stayed in Cleveland for nearly three decades. In 1946, the genius of George Szell took the helm for the next quarter-century and the last half-century has been shared by Lorin Maazel, Christoph von Dohnanyi, and Franz Welser-Most.

* * *

As superlatives accumulate in Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York and Boston, America’s classical music enthusiasts praise the dedicated individuals who bring some of the world’s finest music to our ears.

For nearly a century, Orchestra Hall was the primary performance center for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Those responsible for the initial construction project chose Daniel Burnham as the architect, he had just come-off a rather significate project, being that of the White City, the colloquial name for the Chicago World’s Fair.

By the end of the 20th century an idea for new concert hall was under consideration, but tradition and cost factors proved that renovation was the path to follow. The project called for an extensive list of improvements but foremost were the strengthening of the foundation and the expansion of rehearsal halls, lobbies, meeting rooms, and a public arcade that connects the Michigan Avenue Symphony Center entrance to a new rotunda.

Orchestra halls around the world are renowned for two reasons: acoustics and décor. For the musicians, the acoustic properties are paramount, but the audience is most enamored with the décor. One feature at Orchestra Hall that is unique is its white stage, unlike any place in the world. Chicagoans love it!

Today, Orchestra Hall remains the home of the CSO and with the expanded facility it appears that the hall will service the orchestra for another century.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Theodore Thomas first appeared in 1891. Through the years, Orchestra Hall has been their home and primary performance venue, but in the summer months, since 1905, when the concerts move outside, the CSO travels to the Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, Illinois. The Ravinia Festival is the oldest outdoor venue in the United States.

The Chicago Symphony has amassed an extensive discography. Recordings by the CSO have earned 63 Grammy Awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Beginning in May 1916, Frederick Stock and the orchestra recorded the Wedding March from Felix Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Columbia Records. The CSO’s numerous recordings for Columbia and RCA Victor were some of the first (1925) electric recordings made.

The tradition of recordings continued after Stock’s death in 1942, with Rafael Kubelík, and many of the world’s foremost conductors: including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Georg Solti, and Riccardo Muti.

* * *

The Academy of Music, South Broad Street, Philadelphia

For nearly a century, Orchestra Hall was the primary performance center for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Those responsible for the initial construction project chose Daniel Burnham as the architect, he had just come-off a rather significate project, being that of the White City, the colloquial name for the Chicago World’s Fair.

By the end of the 20th century an idea for new concert hall was under consideration, but tradition and cost factors proved that renovation was the path to follow. The project called for an extensive list of improvements but foremost were the strengthening of the foundation and the expansion of rehearsal halls, lobbies, meeting rooms, and a public arcade that connects the Michigan Avenue Symphony Center entrance to a new rotunda.

Orchestra halls around the world are renowned for two reasons: acoustics and décor. For the musicians, the acoustic properties are paramount, but the audience is most enamored with the décor. One feature at Orchestra Hall that is unique is its white stage, unlike any place in the world. Chicagoans love it!

Today, Orchestra Hall remains the home of the CSO and with the expanded facility it appears that the hall will service the orchestra for another century.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Theodore Thomas first appeared in 1891. Through the years, Orchestra Hall has been their home and primary performance venue, but in the summer months, since 1905, when the concerts move outside, the CSO travels to the Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, Illinois. The Ravinia Festival is the oldest outdoor venue in the United States.

The Chicago Symphony has amassed an extensive discography. Recordings by the CSO have earned 63 Grammy Awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Beginning in May 1916, Frederick Stock and the orchestra recorded the Wedding March from Felix Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Columbia Records. The CSO’s numerous recordings for Columbia and RCA Victor were some of the first (1925) electric recordings made.

The tradition of recordings continued after Stock’s death in 1942, with Rafael Kubelík, and many of the world’s foremost conductors: including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Georg Solti, and Riccardo Muti.

* * *

The Academy of Music, South Broad Street, Philadelphia

The Academy of Music is a hall for which this writer has a grand respect. It was the site of the first concert I attended in the United States on January 27, 1967. The Vienna Philharmonic was on tour and maestro Josef Krips conducted the overture to Wagner’s Flying Dutchman, a Mozart piano concerto, and Brahms’s Third Symphony.

[Aside: I want to tell you about one of the most bazaar coincidences of my life. Fifty years later, in a discussion with Postcard History’s editor, we looked at each other in complete astonishments and realized that we could have met all those years ago. Ray was at the Academy that night with his wife and his parents celebrating his father’s birthday. What a small world it is!]

The Academy was built in 1855 as an opera house. On many occasions each year, opera is still sung at the Academy, making it the oldest building in the United States still in use for its original purpose. Philadelphians call the Academy, the “Grand Old Lady of Locust Street.” (This is indeed a mystery to me since the entrance is on Broad Street.)

In other than arts performances the building hosted the 1872 Republican National Convention where Ulysses S. Grant accepted the nomination for his second term as President. It has been used as a movie set and the site of hundreds of school and university graduations.

Today the Academy is the home of the Pennsylvania Ballet, Opera Philadelphia, and for one-hundred and one years it was the home of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphians played first on November 16, 1900 under the baton of Fritz Scheel.

Early in the orchestra’s history (1912) a young British conductor with a Polish name was hired to be the third conductor – Leopold Stokowski. His first appearance with the orchestra took place on October 11, 1912. (10/11/12 – the numerologists went crazy!)

Everyone loved Leopold! Even Micky Mouse loved Maestro Stokowski for it was Leopold Stokowski with whom Mickey shared the starring role in the movie, Fantasia, produced by the Walt Disney Studios in the fall of 1940.

Stokowski’s contract in Philadelphia was extended year after year and in the end he conducted there for twenty-six years. That was somewhat of a record, at least until the Philadelphians hired their fourth conductor – Eugene Ormandy. Dr. Ormandy became a second long-term music director; his forty-four year tenure became the longest serving conductorship in American music history.

In years gone by the Philadelphians enjoyed a reputation based on a certain something called the Philadelphia Sound. It was a nearly indefinable characteristic of performance that was often described as soft strings, clarion brass and luscious woodwinds. Ask any Philadelphian who attended a concert in the seventy years between 1912 and 1982. They’ll tell you all about it.

* * *

Severance Hall, Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio

The Academy of Music is a hall for which this writer has a grand respect. It was the site of the first concert I attended in the United States on January 27, 1967. The Vienna Philharmonic was on tour and maestro Josef Krips conducted the overture to Wagner’s Flying Dutchman, a Mozart piano concerto, and Brahms’s Third Symphony.

[Aside: I want to tell you about one of the most bazaar coincidences of my life. Fifty years later, in a discussion with Postcard History’s editor, we looked at each other in complete astonishments and realized that we could have met all those years ago. Ray was at the Academy that night with his wife and his parents celebrating his father’s birthday. What a small world it is!]

The Academy was built in 1855 as an opera house. On many occasions each year, opera is still sung at the Academy, making it the oldest building in the United States still in use for its original purpose. Philadelphians call the Academy, the “Grand Old Lady of Locust Street.” (This is indeed a mystery to me since the entrance is on Broad Street.)

In other than arts performances the building hosted the 1872 Republican National Convention where Ulysses S. Grant accepted the nomination for his second term as President. It has been used as a movie set and the site of hundreds of school and university graduations.

Today the Academy is the home of the Pennsylvania Ballet, Opera Philadelphia, and for one-hundred and one years it was the home of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphians played first on November 16, 1900 under the baton of Fritz Scheel.

Early in the orchestra’s history (1912) a young British conductor with a Polish name was hired to be the third conductor – Leopold Stokowski. His first appearance with the orchestra took place on October 11, 1912. (10/11/12 – the numerologists went crazy!)

Everyone loved Leopold! Even Micky Mouse loved Maestro Stokowski for it was Leopold Stokowski with whom Mickey shared the starring role in the movie, Fantasia, produced by the Walt Disney Studios in the fall of 1940.

Stokowski’s contract in Philadelphia was extended year after year and in the end he conducted there for twenty-six years. That was somewhat of a record, at least until the Philadelphians hired their fourth conductor – Eugene Ormandy. Dr. Ormandy became a second long-term music director; his forty-four year tenure became the longest serving conductorship in American music history.

In years gone by the Philadelphians enjoyed a reputation based on a certain something called the Philadelphia Sound. It was a nearly indefinable characteristic of performance that was often described as soft strings, clarion brass and luscious woodwinds. Ask any Philadelphian who attended a concert in the seventy years between 1912 and 1982. They’ll tell you all about it.

* * *

Severance Hall, Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio

Adelia Prentiss Hughes, a native of Cleveland had worked for the better part of the 1920s in her quest to create a world-class civic orchestra for the city of her birth. For the most part, she enjoyed grand success with several musical achievements to her credit, but by the end of the decade, Hughes had devoted herself to the construction of a permanent home for the Orchestra. Since the founding of the orchestra in the previous decade they performed in no less than three different locales.

In 1926 campaigning for funds, both public or private was a popular cause with high public interest, but the interest generated very little response. Then like a bolt of lightning at a concert in 1928 John L. Severance and his wife Elizabeth went to the stage unannounced and pledged one-million dollars toward a new Cleveland Orchestra Concert Hall.

The first gala concert occurred on February 4, 1931. In the weeks and months that followed, news of some very surprising features of Cleveland’s new “Palace of Music” were revealed. One such feature was, according to the wire-services for several area newspapers, the in-house radio station. The station, designed specifically to broadcast classical music, thrilled music lovers across the country. During the March that followed, it was announced that the funds needed to complete the payments on the hall had been raised due to high ticket sales and tens-of-thousands in additional donations by the public. The final cost: $2,500,000.

The Cleveland Orchestra is the youngest of the “Big Five.” Founded in 1918 by a pianist who enjoyed an international reputation, Adelia Prentiss Hughes. Born in Cleveland at the end of the Civil War, Miss Hughes attended and graduated from Vassar College with a degree in music. While at college Adelia sang in the glee club choir with a sister-student named Elizabeth Rockefeller, who just happened to be the oldest daughter of a man name John D. Rockefeller. That connection proved to be invaluable in the years ahead.

Miss Hughes’s personal history would fill volumes in the book of musical achievements, one of which was the first ever recording in 1924 of Tchaikovsky’s The Year 1812 Solemn Overture.

Conductors at Cleveland enjoyed five long-term periods of glorious success beginning with a Russian born conductor/composer name Nikolai Sokoloff. Sokoloff stayed in Cleveland for nearly three decades. In 1946, the genius of George Szell took the helm for the next quarter-century and the last half-century has been shared by Lorin Maazel, Christoph von Dohnanyi, and Franz Welser-Most.

* * *

As superlatives accumulate in Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York and Boston, America’s classical music enthusiasts praise the dedicated individuals who bring some of the world’s finest music to our ears.

Adelia Prentiss Hughes, a native of Cleveland had worked for the better part of the 1920s in her quest to create a world-class civic orchestra for the city of her birth. For the most part, she enjoyed grand success with several musical achievements to her credit, but by the end of the decade, Hughes had devoted herself to the construction of a permanent home for the Orchestra. Since the founding of the orchestra in the previous decade they performed in no less than three different locales.

In 1926 campaigning for funds, both public or private was a popular cause with high public interest, but the interest generated very little response. Then like a bolt of lightning at a concert in 1928 John L. Severance and his wife Elizabeth went to the stage unannounced and pledged one-million dollars toward a new Cleveland Orchestra Concert Hall.

The first gala concert occurred on February 4, 1931. In the weeks and months that followed, news of some very surprising features of Cleveland’s new “Palace of Music” were revealed. One such feature was, according to the wire-services for several area newspapers, the in-house radio station. The station, designed specifically to broadcast classical music, thrilled music lovers across the country. During the March that followed, it was announced that the funds needed to complete the payments on the hall had been raised due to high ticket sales and tens-of-thousands in additional donations by the public. The final cost: $2,500,000.

The Cleveland Orchestra is the youngest of the “Big Five.” Founded in 1918 by a pianist who enjoyed an international reputation, Adelia Prentiss Hughes. Born in Cleveland at the end of the Civil War, Miss Hughes attended and graduated from Vassar College with a degree in music. While at college Adelia sang in the glee club choir with a sister-student named Elizabeth Rockefeller, who just happened to be the oldest daughter of a man name John D. Rockefeller. That connection proved to be invaluable in the years ahead.

Miss Hughes’s personal history would fill volumes in the book of musical achievements, one of which was the first ever recording in 1924 of Tchaikovsky’s The Year 1812 Solemn Overture.

Conductors at Cleveland enjoyed five long-term periods of glorious success beginning with a Russian born conductor/composer name Nikolai Sokoloff. Sokoloff stayed in Cleveland for nearly three decades. In 1946, the genius of George Szell took the helm for the next quarter-century and the last half-century has been shared by Lorin Maazel, Christoph von Dohnanyi, and Franz Welser-Most.

* * *

As superlatives accumulate in Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York and Boston, America’s classical music enthusiasts praise the dedicated individuals who bring some of the world’s finest music to our ears.

Since I grew up in a suburb of Cleveland, I was most interested in the account of that city’s orchestra and its home, Severance Hall.