Hy Mariampolski

New York’s 1913 Armory Show

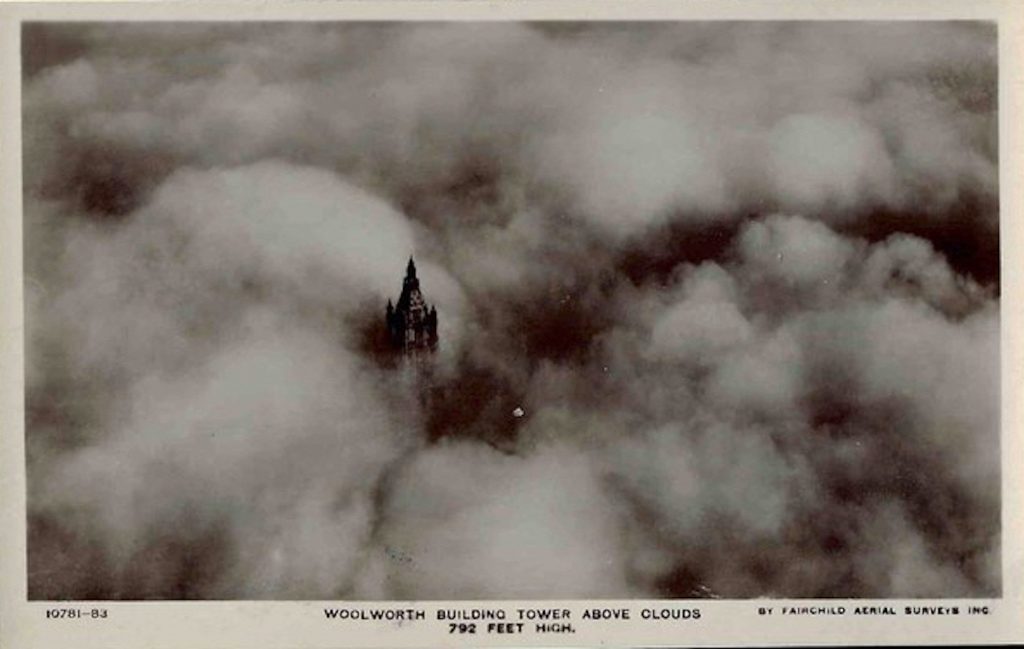

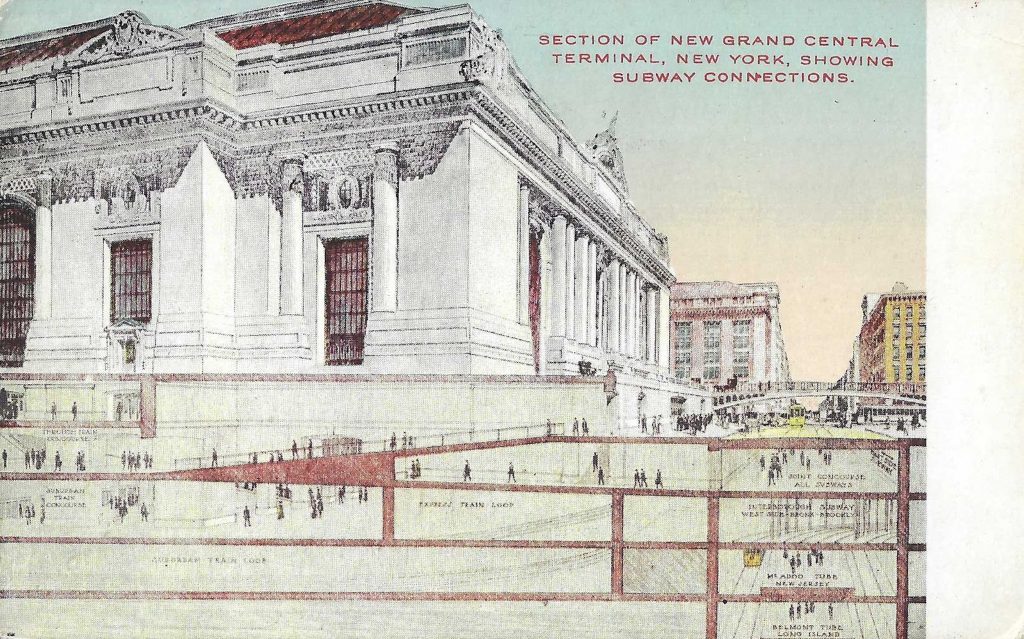

New York’s Winter of 1913 was a period that combined hope and confusion, a sense of excitement and feelings of vulnerability. The newly rebuilt Grand Central Terminal, a masterpiece of Beaux-Arts architecture, reassured New Yorkers that their city would remain the nexus of international commerce. The world’s tallest building, the Woolworth Tower, a cathedral to 5¢ and 10¢ retailing jutting 792 feet into the clouds, stood on Lower Broadway opposite the city’s municipal government and communications hub.

The Woolworth Building’s April 24, 1913, opening was deemed so momentous that F. W. Woolworth, the corporation’s owner celebrated with over 900 guests and at exactly 7:30 pm, newly inaugurated U. S. President Woodrow Wilson pushed a button in Washington, D.C. to turn on the Woolworth Tower’s lights.

The newly minted tallest building in the world –

The Woolworth Tower peeks above the clouds.

The newly rebuilt Grand Central Terminal

shows off its latest technology.

Immigration was another topic on people’s minds through that year. Between 1900 and 1915, more than 15 million immigrants arrived in the United States. In 1910, three-fourths of New York City’s population were either immigrants or first-generation Americans – the sons and daughters of immigrants.

Thrown into the mix was New York’s own coterie of ideological, political, and social dissidents assembled in Greenwich Village, the neighborhood already established as the city’s hotbed for free-thinking and alternative culture. They came from diverse backgrounds – artists, writers, performers, activists, philosophers, social workers, and poets. They organized through literary salons, journals like the Masses and groups like the Wobblies. Dissident intellectuals sought to go beyond reformism to a radical critique of the fundamental bases of society. Max Eastman, John Reed, Emma Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Alfred Stieglitz, Dorothy Day, John Sloan – their names have become legendary for their devotion to feminism, radical politics and their critique of the Victorian and Edwardian family structure, sexuality, gender dynamics, and other themes that kept them far to the left of conventional American thinking.

New York should have been a hotbed of artistic creativity during this era, too, but was held back at this moment by the tight grip on artistic development maintained by the National Academy of Design. Disregarding at least 40 years of European artistic development, the Academy could not be moved forward from its devotion to the Classical vocabulary rooted in the esthetics of ancient Greece and Rome.

The time was ripe for an entrepreneurial spirit to start a new organization and bring New York art into the 20th Century. In 1911, American Impressionist Walt Kuhn became that guiding force by founding the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. Together with Arthur Bowen Davies, another European-trained artist who took over the Association’s Presidency, Kuhn traversed Europe, particularly Paris in 1912 meeting at the galleries and studios promoting and recruiting for their project – a definitive show about modern art, its antecedents, its present and its future. He was brash and optimistic:

“We will show New York something they never dreamed of.”

The Armory Show, an exhibition of some 1,400 works, took place from February 17 to March 15, 1913 at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue and 25th Street. In less than a month it changed the way Americans thought about modern art. It has been called the most important exhibition ever held in the United States.

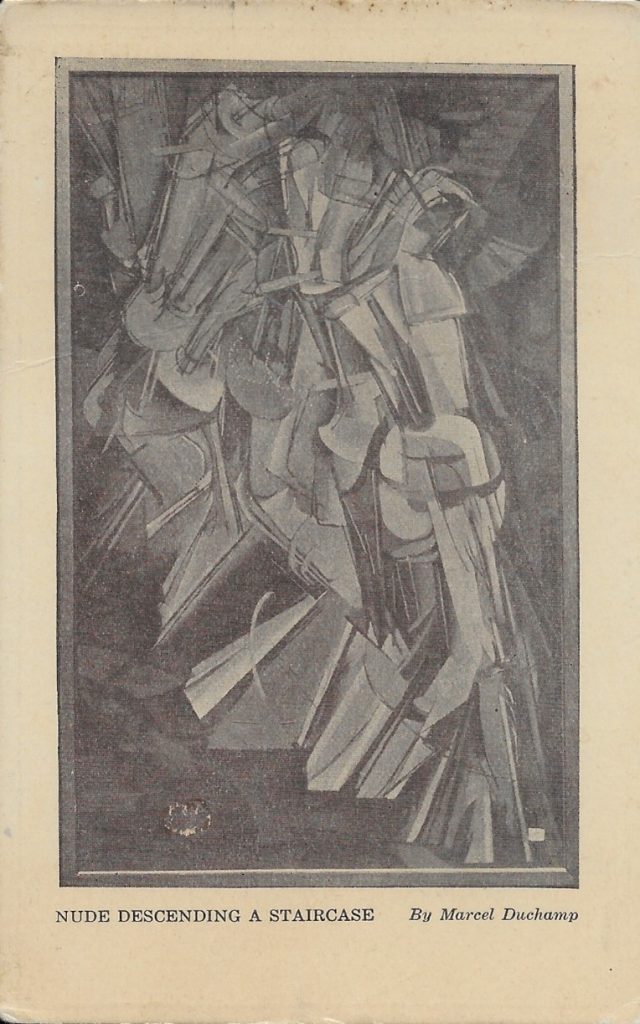

Despite the passage of more than a century, it’s not hard to imagine what it must have been like to see works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, Wassily Kandinsky, Vincent Van Gogh, and many others all together for the very first time.

In understanding the reasons for the success of the venture, we would have to credit Kuhn’s extraordinary foresight in seeking consensus and buy-in from the artists and gallerists who supplied their work.

The show was lightly curated. Not every submission was accepted but an effort was made to admit as wide a sampling of expressive forms as possible. After all, Kuhn was demonstrating the evolution of modern art from Ingres to Matisse.

It was not an easy task. In the decades following the maturing of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, it seemed as though European modernism had exploded like a grenade filled with new ideas about the color palette, form and representation, communicating motion and technology. Schools of artistic approaches emerged calling themselves Fauvists, Cubists and Futurists.

American artists had their own issues – principally, they were tired of being regarded as the step-cousins of modernism. They were looking for their own share of daylight – artists like John Sloan and Robert Henri, whose collaborators in the Ashcan School were rejecting idealization and delving into alternative visions of American reality.

The adept marketer in Walt Kuhn had another trick up his sleeve. In order to give prospective attendees a chance to sample the exhibit’s range of styles, he issued a collection of more than 50 postcards and gave them out freely. In order to build word-of-mouth marketing, attendees could send these postcards from a conveniently placed mailbox at the exhibit’s exit.

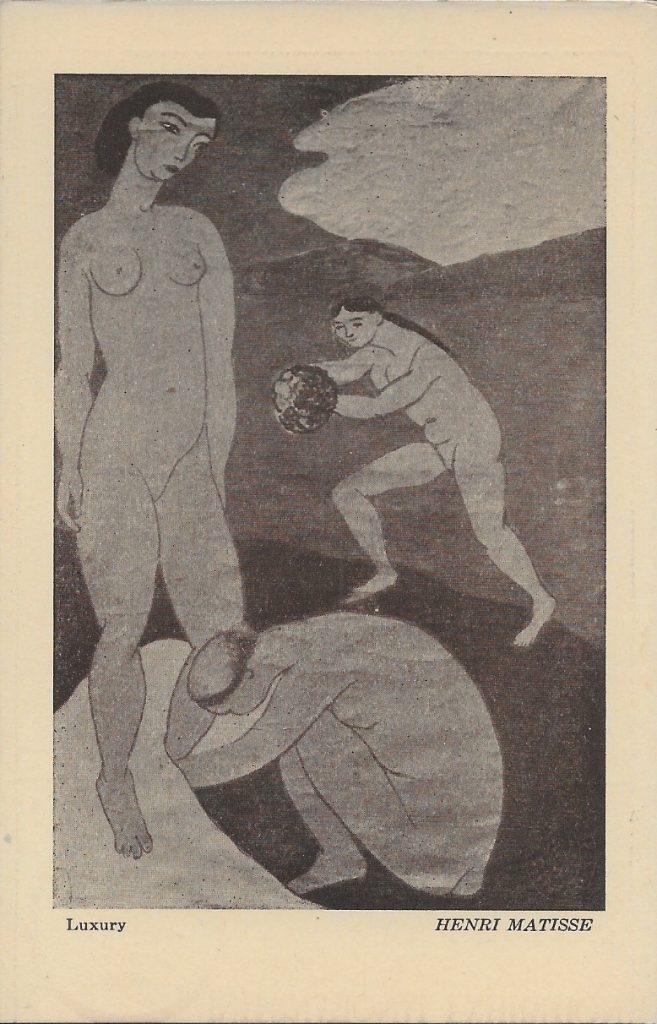

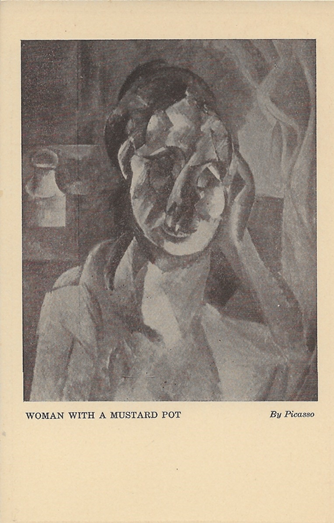

At left, Nude Decending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp; center, Luxury by

Henri Matisse; right, Woman with a Mustard Pot by Picasso.

This postcard set continues to attract avid collectors. Even though they were published as black and white halftones, considering the age and pedigree of the cards the prices of many have exceeded hundreds of dollars – especially if they have a message from a notable correspondent. Generally, the cards are scarce but occasionally a shopper with a discerning eye can find Armory Show bargains among common art reproduction postcards.

Reactions to the show were mixed at first. Many were overcome by the “Shock of the New.” As the Chicago Tribune reported about viewers of the Cubist, Futurist and Abstract paintings, “There most of them are obliged to laugh, others are struck dumb with an open mouth stare, and a few are seized with deep despair.”

A more conclusive summary several weeks later pointed out, “The exhibition has been a brilliant success in every way. The attendance has been large, and the sales of pictures numerous and remunerative. The exhibition has set the town talking and thinking and cannot fail to rank as a most inspiring event.” The Show continued its critical and commercial success when it moved on to Chicago and Boston.

The artwork that generated the most headlines was Duchamp’s now-famous painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1912). To the eyes of Armory Show visitors, there was no nude figure in sight. Ironically, nowadays the Duchamp is the rarest and most desirable of the postcards.

The powerful impact of the Armory Show on American collectors broke the power of the National Academy of Design. The show’s satisfied customers would contribute to the founding of New York’s modern art museums—including the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum. The American artist Edward Hopper made his very first sale at the Armory Show.

It seems every correspondence from this group brings me delight! Once again I am entertained and educated at the same time. What a blessing to my life!

Oh how wonderful to have Hy Mariampolski dip in and share his knowledge and experience with this event, and to whet our appetite for these special black and white postcards that were created to help promote “The Armory Show of 1913.” This is so wonderful and I love how he starts out and tells what is going on in town during that time. I have never seen the postcards from Chicago and Boston….always something new to learn about and share. BRAVO to Hy, and to postcardhistory.net for bringing all of this to our attention. Art history lovers are all smiling… Read more »

I learned of John Sloan when a U.S. postage stamp depicting his painting “The Wake of the Ferry” was issued in 1971, the centennial year of his birth. I was a budding philatelist at the time.

Thanks for this article!

Another great article! Interesting that the postcards were never sent to anyone. Does that add or subtract from their value? My father was something of a chess prodigy and was scheduled to play Duchamp at the Marshall Chess Club. Duchamp cancelled at the last minute. We have several paintings by Cecil Bell, a student of John Sloan.

I smell a post card history book in the making! Great piece. Of course I have studied the Armory show and it’s artists. So exciting to see the post cards. I make post cards as an artist announcing my books and events. It’s nice to know such items get saved and written about decades later!

Thanks for including me in your history lesson! I learned about the 1913 exhibit fairly recently. It’s exciting to read about the interaction of these artists when they were young.

Hy is to be thanked and congratulated for an insightful, delightful introduction to this postcard (and, oh yes, art world) landmark event. The postcards are terrific to see, especially the reverses of the rarities from the Chicago and Boston venues. Seeing the fronts of these would be edifying, as we might intuit something about the publishers in each locale by their choice of subject. For further info, postcard collectors will find especially useful the listing of 48 Armory Show postcards on pp.209-210 of Fred and Mary Megson’s “American Exposition Postcards 1870-1920”, copyright 1992. Another reference for postcard collectors is the… Read more »