Hy Mariampolski

Deciphering Coney Island

Part II

I’m glad you came back for Part 2 of

Deciphering Coney Island. Part 1 was the last article in Postcard History’s third year; Part 2 is the first article of year four. We’ll spend more time looking at the rides and amusements at Coney Island. We will offer a thorough and sensitive analysis of the shameful “freak shows” and “human zoos” that brought crowds and cash to the exhibitors. We will examine the factors that led to Coney Island’s decline in the years following World War II. And we’ll provide the answer to that controversial question: What was Coney Island’s favorite food?

* * *

As improved transportation systems, subways and streetcars continued to bring crowds to Coney Island and new temptations were built to absorb them, the utopian impulse that animated much of the area’s early development began to dissipate. At first, Coney Island was expected to stand for American democracy and freedom from the strictures that interfered with individualism. Technology was expected to be mobilized to advance human freedom.

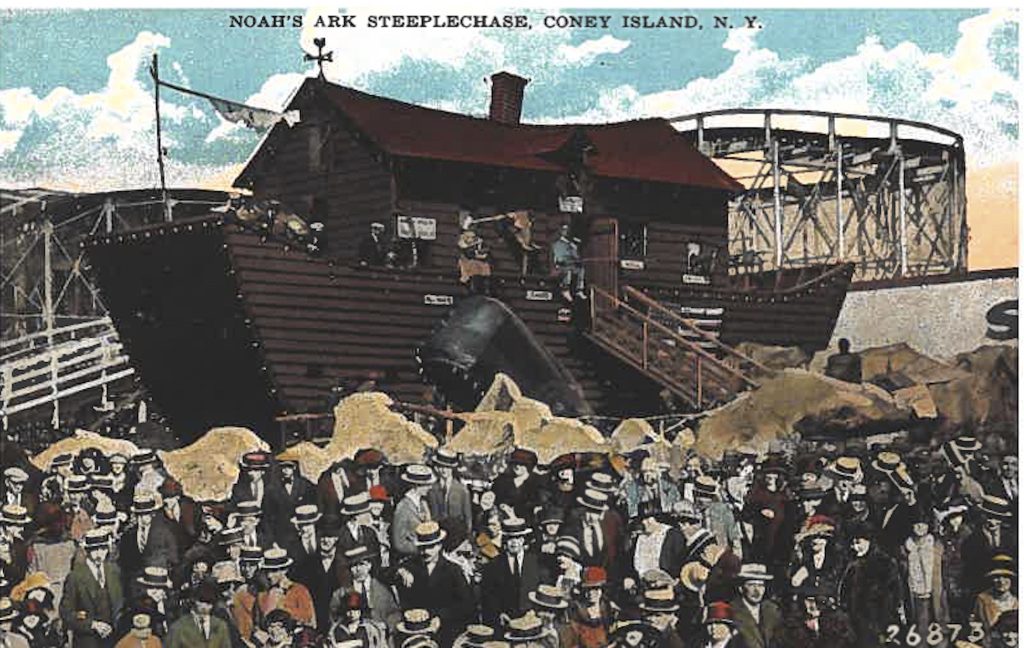

Eventually the voices of the idealists were silenced a bit and the loudest were motivated by competition and sensationalism. Technology was mobilized to see who could produce the biggest, noisiest and the fastest rides. Not even Noah’s Ark, an exhibit where we would expect to see a huge vessel slithering silently toward a landfall, could avoid becoming surrounded by a roller coaster.

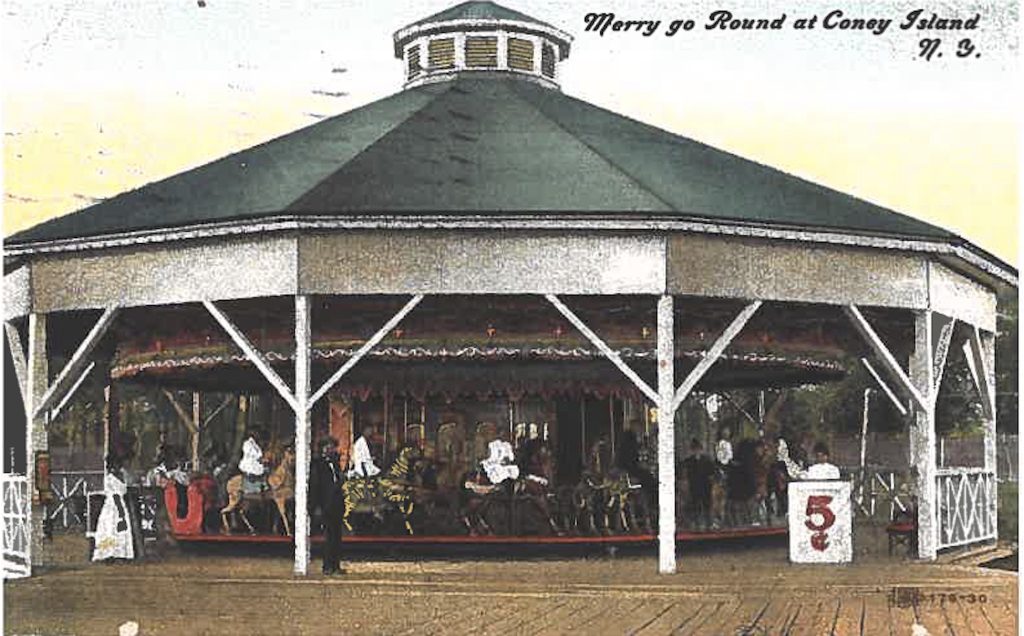

Coney Island produced its share of traditional rides, like merry-go-rounds and miniature railroads that appeared all over America through the early 20

th century in carnivals, parks, and fairs. Immigrant craftsmen from Europe were meeting a desire for new structures of leisure in demand by citizens in growing cities everywhere. The “Coney Island Style” of merry-go-round’s horses were uniquely ornate with large, bejeweled saddles atop highly animated carved creatures.

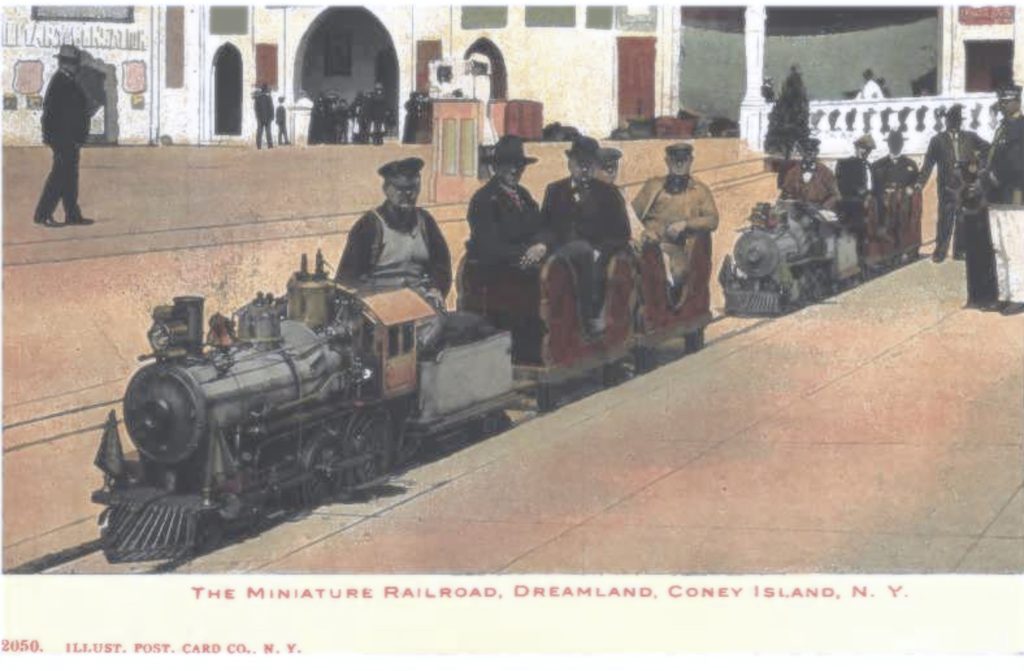

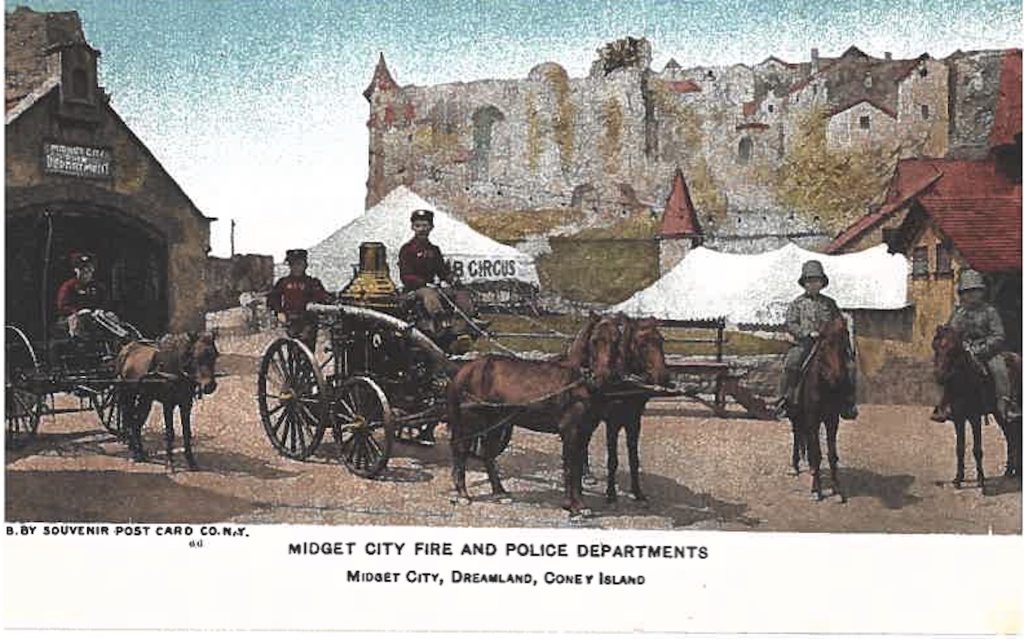

The miniature railway at Dreamland ran through a Swiss Alpine landscape, imitation Venetian canals with gondolas and on through the park’s human zoos. One called the “Lilliputian Village” was inhabited by three hundred dwarves, the other a fantasy about the Igorot people of the Philippines, and finally, the railway ran through a firefighting exhibit. The multi-ethnic Philippines, a South Pacific archipelago had recently been acquired by the United States as a protectorate following the Spanish-American War, along with several Caribbean colonies, like Cuba and Puerto Rico. Curiosity about the Philippines was turned by entertainment producers into treating one of their ethnic groups like confined prisoners while Coney Islanders gawked at their nearly naked costumes and fervid ceremonies.

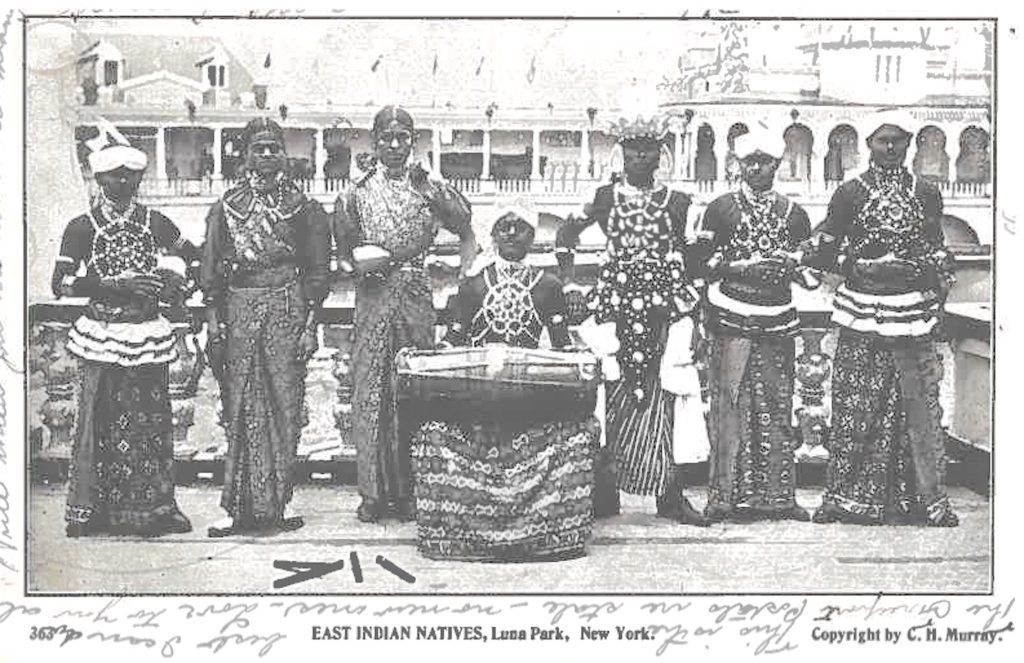

The human zoo represents the underside of Darwinian thinking applied at a time when ideas of social and cultural superiority were considered respectable, and imperialism was the order of the day. Postcards without self-consciousness or guilt depict these as human curiosities rather than as mistreatment of other human beings without cause, just for being different. This happened not only at Dreamland but as this postcard of East Indian Natives shows, also at Luna Park.

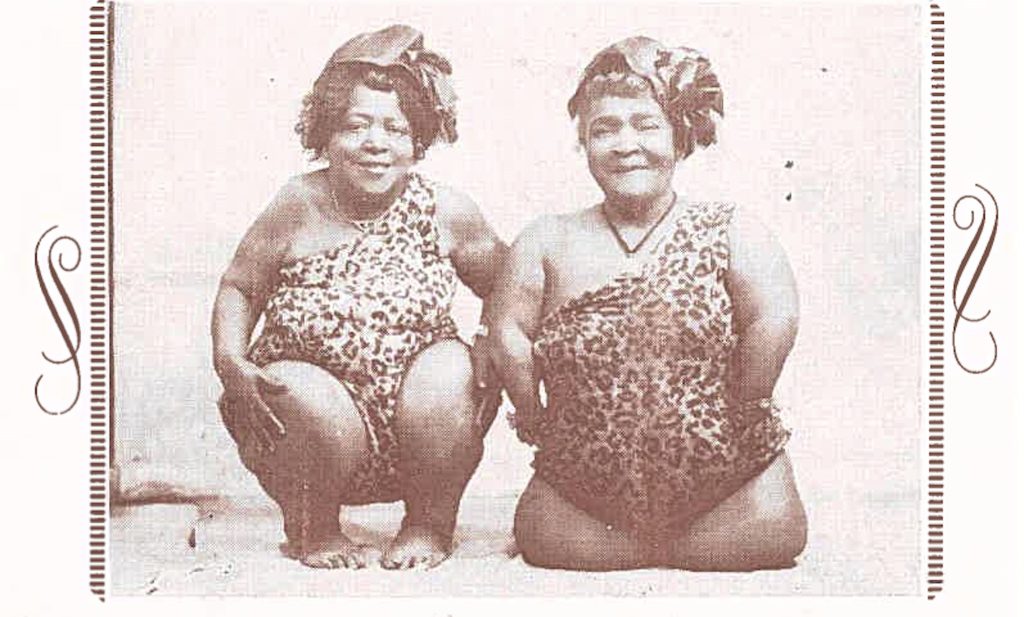

But that’s not all. The growth of the amusement park at Coney Island came at a time when people suffering from deformities or disfigurements from severe injuries of birth or battle were regarded as “freaks” without regard to their feelings about being relegated to an offensive social category. Many of these folks were encouraged to display themselves in “side shows” among the amusements. Producing postcard imagery depicting their deformities was a way of making money.

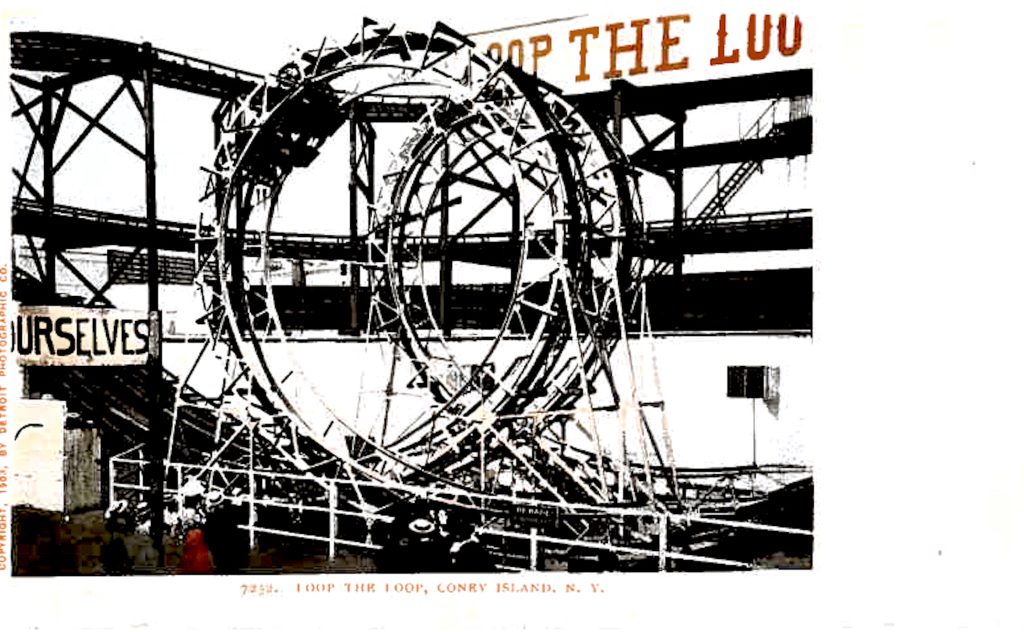

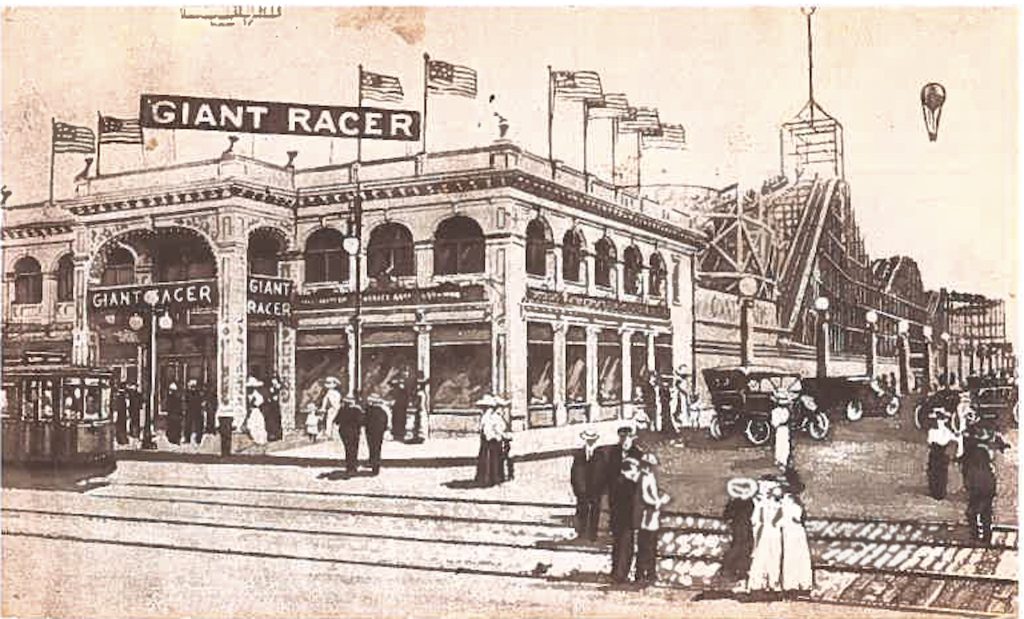

When Dreamland was created in 1904 by Brooklyn real estate developer and former state senator William H. Reynolds, it was intended to be a classier and more refined alternative to Luna Park. Competitive realities ensured that these ideals did not last long. By the time the park burned in 1911, Dreamland had installed its own version of the Loop the Loop and tried to keep up with independent roller coaster operators who claimed to have the largest and the fastest. Dreamland also featured the side show and a hotel managed by one of their partners the Dicker family. Luna Park, however, was said to be better managed and simply kept expanding more profitably.

In what was probably the height of side show sensationalism, Dreamland featured a set of infant incubators – not yet approved by hospitals – for premature babies, in this case triplets who were members of the Dicker family. We’re happy to report that two of the children survived to adulthood, although early press reports worried that all had been consumed by the flames.

Another publicity stunt upended by the conflagration, involved Broadway starlet Marie Dressler who had been recruited as team leader for a group of boys dressed as imps in red velvet, selling peanuts and popcorn at the park. Part of the story line involved a love affair going on between Dressler and the dashing one-armed, handlebar-mustachioed Captain Jack Bonavita, lion tamer at Bostock’s Menagerie who had acquired his injury in a taming accident.

Captain Bonavita performed heroically as the fire raged but between those lions that escaped and were shot and those tragically locked in their cages about 60 animals were lost when the fire destroyed Dreamland.

Luna Park did not necessarily do well when its main competitor was destroyed. After hitting a peak at the end of the first decade of the 20

th century, when all three parks and many independents were active, Coney Island went into a long, slow decline. The high flying 20s had to deal with Prohibition and the 30s experienced the Depression. Luna Park was constantly challenged to keep its offerings fresh and to eliminate rides and spectacles that were no longer attracting customers. Ownership and management changed constantly.

By the end of the 30s, things began to feel tawdry and dated. Even the side shows began to move from freaks to “hootchie-cootchie” (erotic shows) to bring in customers.

In the aftermath of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair, some of the exhibits and rides were moved to Coney Island but this was not enough to relieve the area of its doldrums, especially since wartime civil defense required the lights to be kept down. When Luna Park burned in 1944, civic leaders began to think of other uses for its acreage.

The

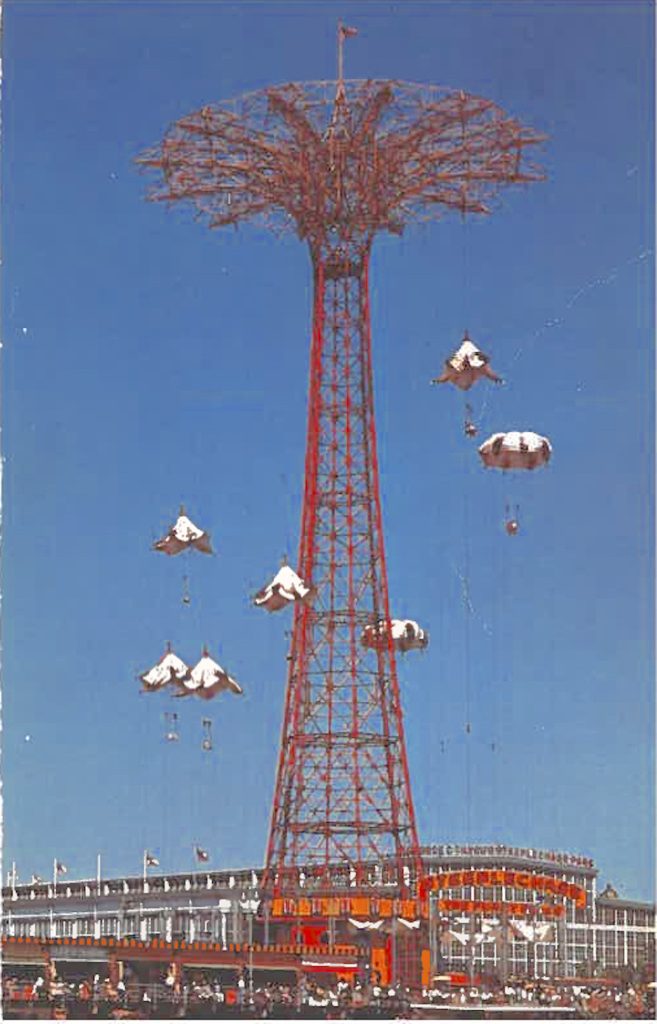

Parachute Jump – one of the popular rides from the New York World’s Fair that found a new home in Coney Island. It’s still here.

The

Cyclone is another legacy survivor at Coney Island. It is considered the best roller coaster in the world by many who have enjoyed a ride.

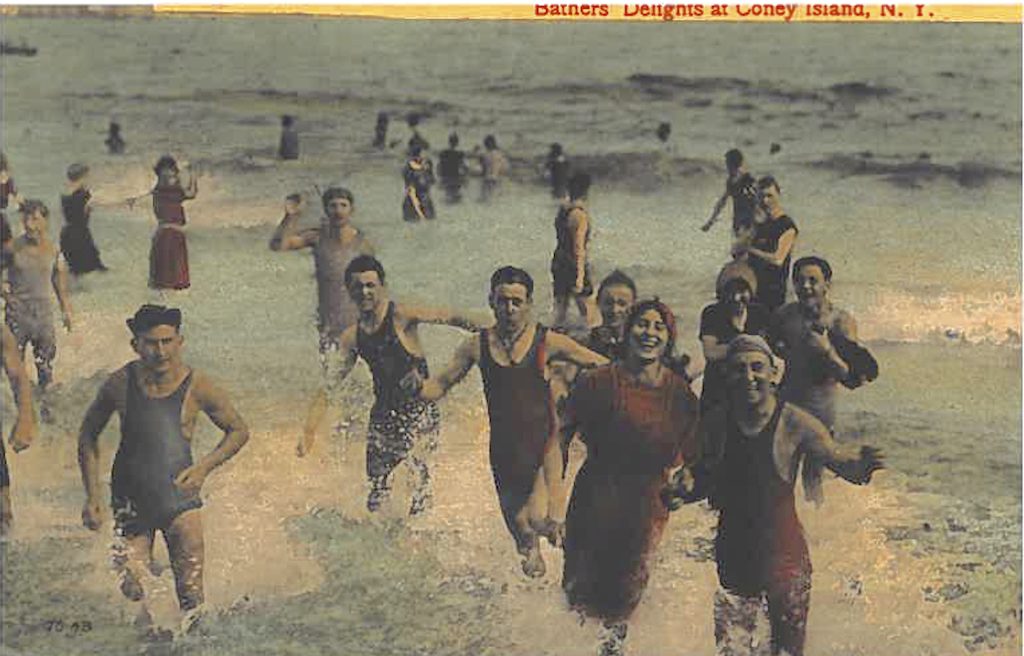

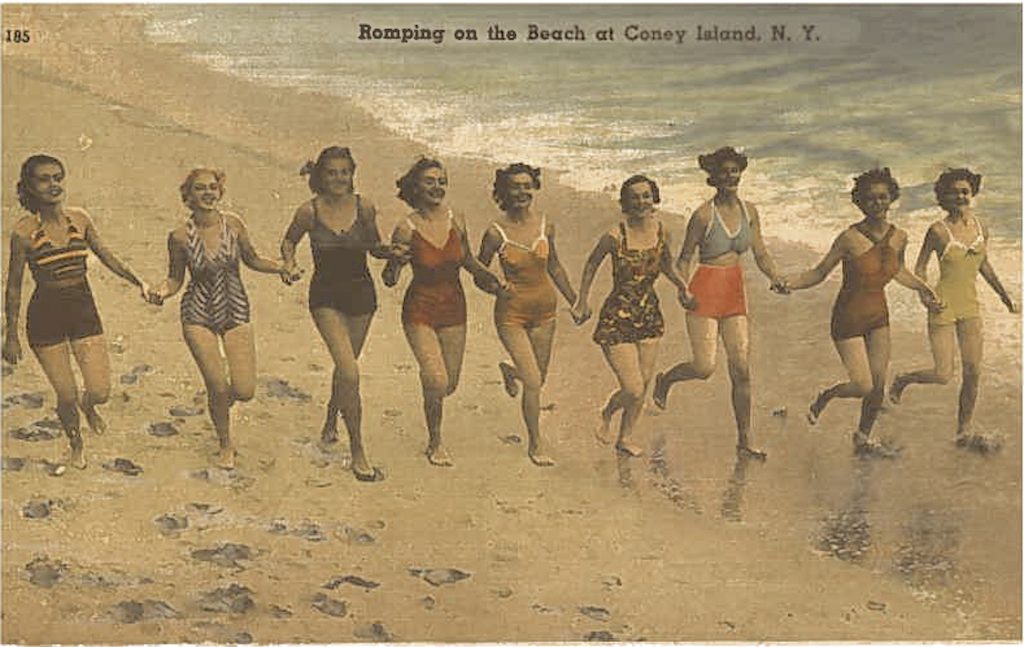

Fortunately, Coney Island has always had an ample and inviting bathing beach that has forever welcomed crowds from all over New York and it is still accessible by subway. Postcards are delightful for illustrating the changes in bathing attire over time. The scene has changed considerably, and bathers are nowadays wearing much less than the garments recorded in these postcards.

Steeplechase Park was the last of the major Coney Island parks to go out of business. During the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair, attendance at Coney Island was hurt so badly that many decided that it was time to pay attention to trends such as more fires and accidents, rising crime rates, increasing suburbanization, growing preference for automobile travel, movement to other forms of leisure and growing preference for other travel destinations. All these trends contributed to the demise of Coney Island as an entertainment venue. Coney Island’s reign as the world’s largest amusement park from the 1880s to the 1950s came to an end.

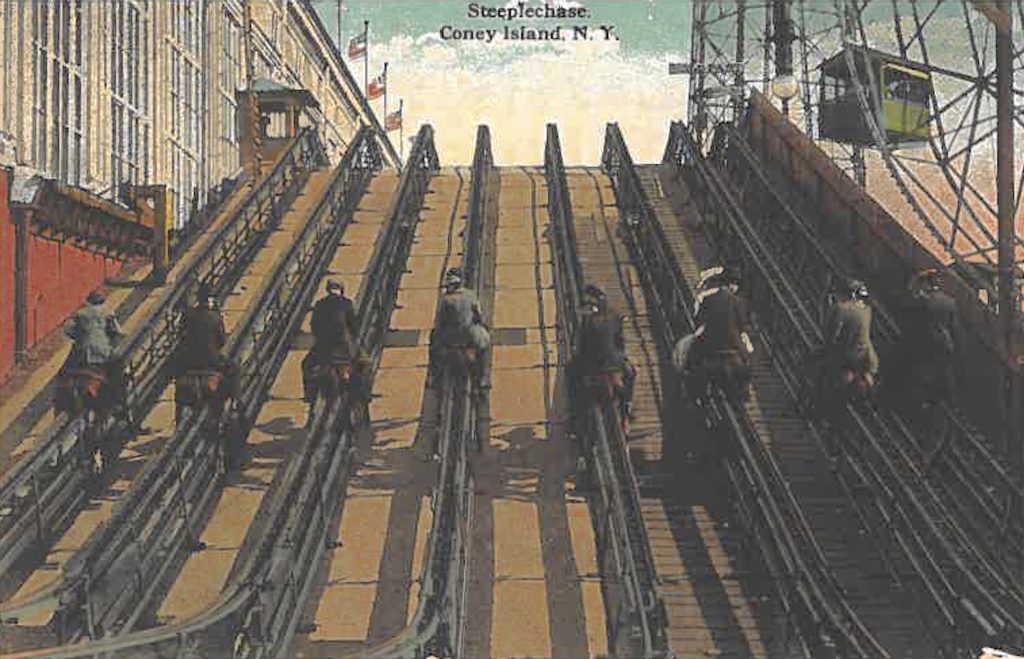

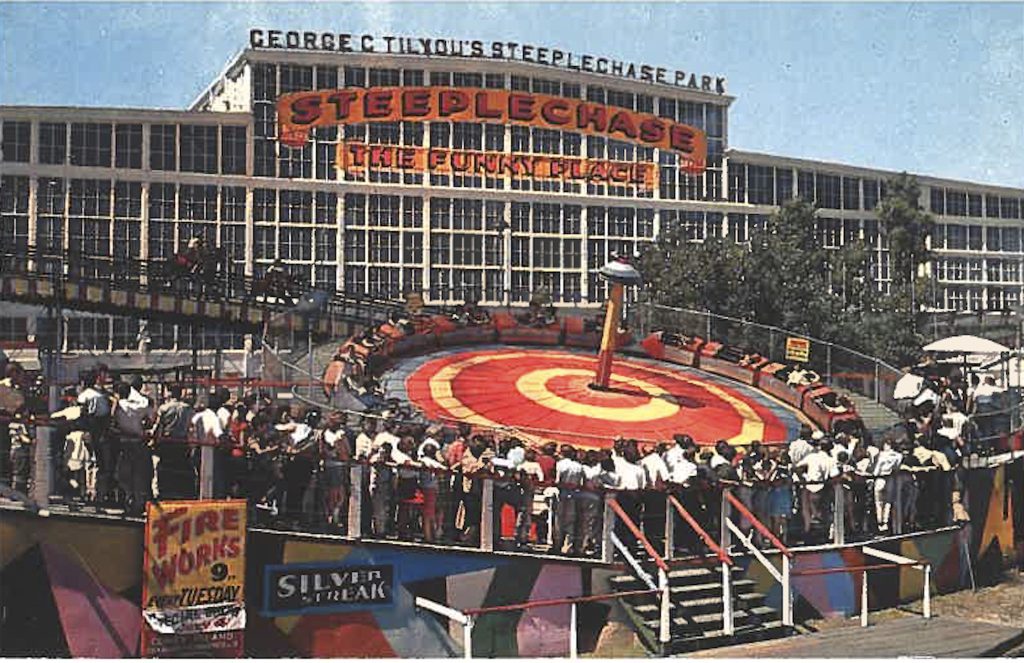

Nevertheless, the Steeplechase racetrack and many of the park’s rides remain a precious memory to many who recall the fun of completing the racecourse and entering Steeplechase’s Pavilion of Fun through a revolving barrel. There, stumbling and disoriented after traversing the wheel, you were in a world dominated by a sadistic and insulting dwarf clown who wielded instruments for titillating observers in the Pavilion’s audience. His most potent weapons were an electrified cattle prod and a narrow pipe for delivering blasts of air for blowing up young ladies’ skirts, exposing their legs or more.

* * *

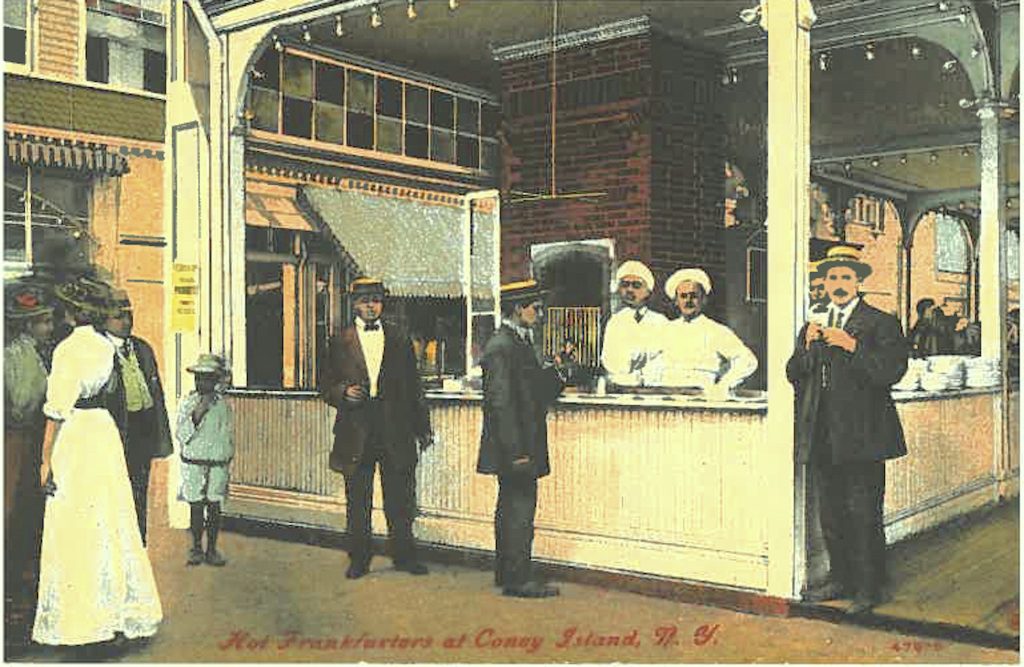

And, there is the question of food! What was Coney Island’s favorite food?

That’s easy – the Hot Dog. In many locations across America, hot dogs in a bun continue to be named after the amusement park as, for example, “Coney Island hots.” Some call them frankfurters or franks, recalling their point of origin. One of the leading brands of hot dogs on the market, Nathan’s, continues to use its own connection with Coney Island in its marketing. Nathan’s proudly sponsors the annual hot dog eating competition in today’s much smaller amusement area to reinforce its brand image. Since Nathan’s leading competitor, Hebrew National, uses its connections with the Deity to promote its own 100% Kosher hot dogs, we would imagine that a tie to Coney Island continues to hold some marketing power.

Coney Island produced its share of traditional rides, like merry-go-rounds and miniature railroads that appeared all over America through the early 20th century in carnivals, parks, and fairs. Immigrant craftsmen from Europe were meeting a desire for new structures of leisure in demand by citizens in growing cities everywhere. The “Coney Island Style” of merry-go-round’s horses were uniquely ornate with large, bejeweled saddles atop highly animated carved creatures.

Coney Island produced its share of traditional rides, like merry-go-rounds and miniature railroads that appeared all over America through the early 20th century in carnivals, parks, and fairs. Immigrant craftsmen from Europe were meeting a desire for new structures of leisure in demand by citizens in growing cities everywhere. The “Coney Island Style” of merry-go-round’s horses were uniquely ornate with large, bejeweled saddles atop highly animated carved creatures.

The miniature railway at Dreamland ran through a Swiss Alpine landscape, imitation Venetian canals with gondolas and on through the park’s human zoos. One called the “Lilliputian Village” was inhabited by three hundred dwarves, the other a fantasy about the Igorot people of the Philippines, and finally, the railway ran through a firefighting exhibit. The multi-ethnic Philippines, a South Pacific archipelago had recently been acquired by the United States as a protectorate following the Spanish-American War, along with several Caribbean colonies, like Cuba and Puerto Rico. Curiosity about the Philippines was turned by entertainment producers into treating one of their ethnic groups like confined prisoners while Coney Islanders gawked at their nearly naked costumes and fervid ceremonies.

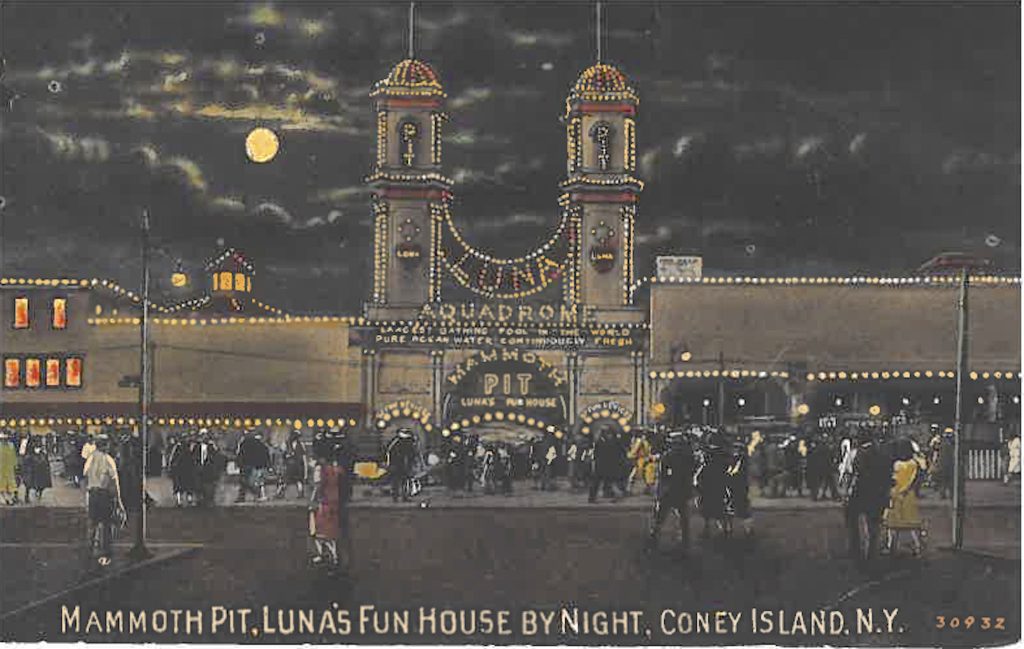

The human zoo represents the underside of Darwinian thinking applied at a time when ideas of social and cultural superiority were considered respectable, and imperialism was the order of the day. Postcards without self-consciousness or guilt depict these as human curiosities rather than as mistreatment of other human beings without cause, just for being different. This happened not only at Dreamland but as this postcard of East Indian Natives shows, also at Luna Park.

The miniature railway at Dreamland ran through a Swiss Alpine landscape, imitation Venetian canals with gondolas and on through the park’s human zoos. One called the “Lilliputian Village” was inhabited by three hundred dwarves, the other a fantasy about the Igorot people of the Philippines, and finally, the railway ran through a firefighting exhibit. The multi-ethnic Philippines, a South Pacific archipelago had recently been acquired by the United States as a protectorate following the Spanish-American War, along with several Caribbean colonies, like Cuba and Puerto Rico. Curiosity about the Philippines was turned by entertainment producers into treating one of their ethnic groups like confined prisoners while Coney Islanders gawked at their nearly naked costumes and fervid ceremonies.

The human zoo represents the underside of Darwinian thinking applied at a time when ideas of social and cultural superiority were considered respectable, and imperialism was the order of the day. Postcards without self-consciousness or guilt depict these as human curiosities rather than as mistreatment of other human beings without cause, just for being different. This happened not only at Dreamland but as this postcard of East Indian Natives shows, also at Luna Park.

But that’s not all. The growth of the amusement park at Coney Island came at a time when people suffering from deformities or disfigurements from severe injuries of birth or battle were regarded as “freaks” without regard to their feelings about being relegated to an offensive social category. Many of these folks were encouraged to display themselves in “side shows” among the amusements. Producing postcard imagery depicting their deformities was a way of making money.

But that’s not all. The growth of the amusement park at Coney Island came at a time when people suffering from deformities or disfigurements from severe injuries of birth or battle were regarded as “freaks” without regard to their feelings about being relegated to an offensive social category. Many of these folks were encouraged to display themselves in “side shows” among the amusements. Producing postcard imagery depicting their deformities was a way of making money.

When Dreamland was created in 1904 by Brooklyn real estate developer and former state senator William H. Reynolds, it was intended to be a classier and more refined alternative to Luna Park. Competitive realities ensured that these ideals did not last long. By the time the park burned in 1911, Dreamland had installed its own version of the Loop the Loop and tried to keep up with independent roller coaster operators who claimed to have the largest and the fastest. Dreamland also featured the side show and a hotel managed by one of their partners the Dicker family. Luna Park, however, was said to be better managed and simply kept expanding more profitably.

When Dreamland was created in 1904 by Brooklyn real estate developer and former state senator William H. Reynolds, it was intended to be a classier and more refined alternative to Luna Park. Competitive realities ensured that these ideals did not last long. By the time the park burned in 1911, Dreamland had installed its own version of the Loop the Loop and tried to keep up with independent roller coaster operators who claimed to have the largest and the fastest. Dreamland also featured the side show and a hotel managed by one of their partners the Dicker family. Luna Park, however, was said to be better managed and simply kept expanding more profitably.

In what was probably the height of side show sensationalism, Dreamland featured a set of infant incubators – not yet approved by hospitals – for premature babies, in this case triplets who were members of the Dicker family. We’re happy to report that two of the children survived to adulthood, although early press reports worried that all had been consumed by the flames.

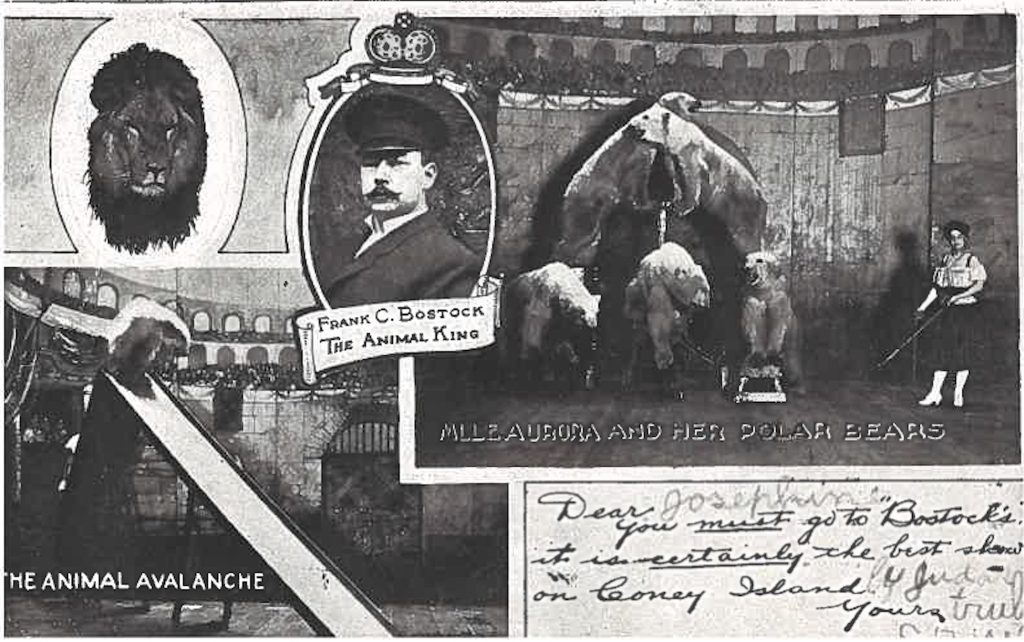

Another publicity stunt upended by the conflagration, involved Broadway starlet Marie Dressler who had been recruited as team leader for a group of boys dressed as imps in red velvet, selling peanuts and popcorn at the park. Part of the story line involved a love affair going on between Dressler and the dashing one-armed, handlebar-mustachioed Captain Jack Bonavita, lion tamer at Bostock’s Menagerie who had acquired his injury in a taming accident.

In what was probably the height of side show sensationalism, Dreamland featured a set of infant incubators – not yet approved by hospitals – for premature babies, in this case triplets who were members of the Dicker family. We’re happy to report that two of the children survived to adulthood, although early press reports worried that all had been consumed by the flames.

Another publicity stunt upended by the conflagration, involved Broadway starlet Marie Dressler who had been recruited as team leader for a group of boys dressed as imps in red velvet, selling peanuts and popcorn at the park. Part of the story line involved a love affair going on between Dressler and the dashing one-armed, handlebar-mustachioed Captain Jack Bonavita, lion tamer at Bostock’s Menagerie who had acquired his injury in a taming accident.

Captain Bonavita performed heroically as the fire raged but between those lions that escaped and were shot and those tragically locked in their cages about 60 animals were lost when the fire destroyed Dreamland.

Luna Park did not necessarily do well when its main competitor was destroyed. After hitting a peak at the end of the first decade of the 20th century, when all three parks and many independents were active, Coney Island went into a long, slow decline. The high flying 20s had to deal with Prohibition and the 30s experienced the Depression. Luna Park was constantly challenged to keep its offerings fresh and to eliminate rides and spectacles that were no longer attracting customers. Ownership and management changed constantly.

By the end of the 30s, things began to feel tawdry and dated. Even the side shows began to move from freaks to “hootchie-cootchie” (erotic shows) to bring in customers.

In the aftermath of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair, some of the exhibits and rides were moved to Coney Island but this was not enough to relieve the area of its doldrums, especially since wartime civil defense required the lights to be kept down. When Luna Park burned in 1944, civic leaders began to think of other uses for its acreage.

The Parachute Jump – one of the popular rides from the New York World’s Fair that found a new home in Coney Island. It’s still here.

Captain Bonavita performed heroically as the fire raged but between those lions that escaped and were shot and those tragically locked in their cages about 60 animals were lost when the fire destroyed Dreamland.

Luna Park did not necessarily do well when its main competitor was destroyed. After hitting a peak at the end of the first decade of the 20th century, when all three parks and many independents were active, Coney Island went into a long, slow decline. The high flying 20s had to deal with Prohibition and the 30s experienced the Depression. Luna Park was constantly challenged to keep its offerings fresh and to eliminate rides and spectacles that were no longer attracting customers. Ownership and management changed constantly.

By the end of the 30s, things began to feel tawdry and dated. Even the side shows began to move from freaks to “hootchie-cootchie” (erotic shows) to bring in customers.

In the aftermath of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair, some of the exhibits and rides were moved to Coney Island but this was not enough to relieve the area of its doldrums, especially since wartime civil defense required the lights to be kept down. When Luna Park burned in 1944, civic leaders began to think of other uses for its acreage.

The Parachute Jump – one of the popular rides from the New York World’s Fair that found a new home in Coney Island. It’s still here.

The Cyclone is another legacy survivor at Coney Island. It is considered the best roller coaster in the world by many who have enjoyed a ride.

The Cyclone is another legacy survivor at Coney Island. It is considered the best roller coaster in the world by many who have enjoyed a ride.

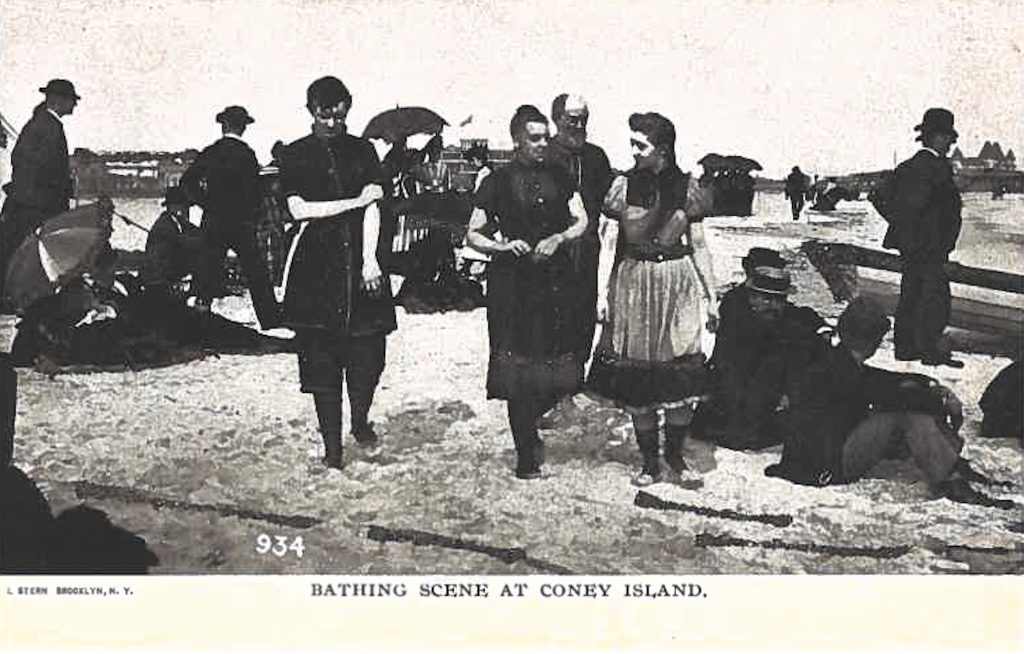

Fortunately, Coney Island has always had an ample and inviting bathing beach that has forever welcomed crowds from all over New York and it is still accessible by subway. Postcards are delightful for illustrating the changes in bathing attire over time. The scene has changed considerably, and bathers are nowadays wearing much less than the garments recorded in these postcards.

Fortunately, Coney Island has always had an ample and inviting bathing beach that has forever welcomed crowds from all over New York and it is still accessible by subway. Postcards are delightful for illustrating the changes in bathing attire over time. The scene has changed considerably, and bathers are nowadays wearing much less than the garments recorded in these postcards.

Steeplechase Park was the last of the major Coney Island parks to go out of business. During the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair, attendance at Coney Island was hurt so badly that many decided that it was time to pay attention to trends such as more fires and accidents, rising crime rates, increasing suburbanization, growing preference for automobile travel, movement to other forms of leisure and growing preference for other travel destinations. All these trends contributed to the demise of Coney Island as an entertainment venue. Coney Island’s reign as the world’s largest amusement park from the 1880s to the 1950s came to an end.

Nevertheless, the Steeplechase racetrack and many of the park’s rides remain a precious memory to many who recall the fun of completing the racecourse and entering Steeplechase’s Pavilion of Fun through a revolving barrel. There, stumbling and disoriented after traversing the wheel, you were in a world dominated by a sadistic and insulting dwarf clown who wielded instruments for titillating observers in the Pavilion’s audience. His most potent weapons were an electrified cattle prod and a narrow pipe for delivering blasts of air for blowing up young ladies’ skirts, exposing their legs or more.

Steeplechase Park was the last of the major Coney Island parks to go out of business. During the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair, attendance at Coney Island was hurt so badly that many decided that it was time to pay attention to trends such as more fires and accidents, rising crime rates, increasing suburbanization, growing preference for automobile travel, movement to other forms of leisure and growing preference for other travel destinations. All these trends contributed to the demise of Coney Island as an entertainment venue. Coney Island’s reign as the world’s largest amusement park from the 1880s to the 1950s came to an end.

Nevertheless, the Steeplechase racetrack and many of the park’s rides remain a precious memory to many who recall the fun of completing the racecourse and entering Steeplechase’s Pavilion of Fun through a revolving barrel. There, stumbling and disoriented after traversing the wheel, you were in a world dominated by a sadistic and insulting dwarf clown who wielded instruments for titillating observers in the Pavilion’s audience. His most potent weapons were an electrified cattle prod and a narrow pipe for delivering blasts of air for blowing up young ladies’ skirts, exposing their legs or more.

* * *

And, there is the question of food! What was Coney Island’s favorite food?

That’s easy – the Hot Dog. In many locations across America, hot dogs in a bun continue to be named after the amusement park as, for example, “Coney Island hots.” Some call them frankfurters or franks, recalling their point of origin. One of the leading brands of hot dogs on the market, Nathan’s, continues to use its own connection with Coney Island in its marketing. Nathan’s proudly sponsors the annual hot dog eating competition in today’s much smaller amusement area to reinforce its brand image. Since Nathan’s leading competitor, Hebrew National, uses its connections with the Deity to promote its own 100% Kosher hot dogs, we would imagine that a tie to Coney Island continues to hold some marketing power.

* * *

And, there is the question of food! What was Coney Island’s favorite food?

That’s easy – the Hot Dog. In many locations across America, hot dogs in a bun continue to be named after the amusement park as, for example, “Coney Island hots.” Some call them frankfurters or franks, recalling their point of origin. One of the leading brands of hot dogs on the market, Nathan’s, continues to use its own connection with Coney Island in its marketing. Nathan’s proudly sponsors the annual hot dog eating competition in today’s much smaller amusement area to reinforce its brand image. Since Nathan’s leading competitor, Hebrew National, uses its connections with the Deity to promote its own 100% Kosher hot dogs, we would imagine that a tie to Coney Island continues to hold some marketing power.

Great Article and post card photos. I love reading and seeing post cards from the defunct amusement parks. We had many in my area of Ohio, small family types that could not keep up with the huge parks like Cedar Point. Many were called Trolly Parks because the Trolly cars would bring people by the thousands. Post cards from these parks are very special to the people who went to them as kids and now the only souvenir they may have of the wonderful times they had with their parents. Thank You for the article it was very enjoyable and… Read more »

A good, enjoyable, informative read. The only thing missing, a hot dog slathered with mustard, ketchup and a bit of relish. B🤓b

A wonderful article which brings back great memories. Thanks, Hy. Also, Koehler issued yet a third version of their popular postcards…in silk.

Hy, Very interesting and well written article. I collect Coney Island postcards and use them in my college history class to illustrate social behavior at the turn of the century. My first interest in the topic was cultivated from my childhood experiences at the New Jersey shore boardwalk in Seaside Heights. I have acquired many of my cards as a member of the Washington Crossing Card Collectors Club which meets the second Monday of each month at the Union Firehouse in Titusville, NJ. Keep up the good work! PS. Nothing better at a Fourth of July picnic than a delicious… Read more »

I spent all my summers from 1954-1964 as season ticket holders of Steeplechase Park. I didn’t see when Luna Park closed it was replaced by low income housing aka “the projects” and that increased crime in the area. Also Steeplechase was exclusive to whites only. Never noticed as a child but in my later years it became apparent. I believe it led to the park closing. Regardless, my fondest childhood memories reside there and one day so will my ashes be spread at the base of Brooklyn’s Eiffel Tower.

Great article with wonderful postcards. Hard to believe growing up not far from Coney Island right over the Queens border in Nassau county that I never went to Coney Island as an amusement park or to the beach. But I did go to Rockaway Playland in Far Rockaway in the late 40’s and early 50’s and spend summers on the beach on Atlantic Beach and Jones Beach. PS had a Nathan’s Hot Dog today from a food truck at a music festival in PA.

Both articles are super analyses of Coney Island’s imprint on and by America! And they are equally important as exposes of the power and importance of postcards for documenting social, economic, industrial, culinary, and almost every other development in our country. In Part I, I was mildly startled by the reference to “‘the first decade’ of the Postcard Craze.” I have always placed that period as being from about 1907 (divided backs and RFD) to 1914 and the wartime closing of the European manufacturers–less than ten years in all. Part II took me right back to my first visit to… Read more »

Fascinating article, Hy! As you no doubt know, the name of the Brooklyn Cyclones, a farm club of the New York Mets, was inspired by the roller coaster that stands to this day.

Everyone seems to forget, corn in the cob, hung from about every food vendor!

Great article, Hy. I love the amusement park postcards. I also love finding images that have been recycled, repurposed, or perhaps even stolen. Case in point is the postcard you included of the Merry-go-round. I’ve attached a postcard of the Merry-Go-Round in Hartford, CT’s Luna Park. Hmmmm, they look awfully similar. I wonder which was the real location, or if there’s a third place where this ride actually was?!

I’ve just recently visit Coney Island I would just reminiscing how more fun more entertainment how it used to be when I was a kid now that I see the present Coney Island it just doesn’t have that same atmosphere that it once had I know things changed but Coney Island is just not the same and it doesn’t have that same feeling