Terry Bryan

Billy Whitla, Kidnapped Child

A parent’s nightmare is the kidnapping of a child. As personally wrenching as such events are for the families, the news media have never been bashful about keeping the stories coming for weeks or months at a time. Before the kidnapping of Charles A. Lindbergh, Junior in 1932, and long before Patty Hearst’s saga played out in 1974, young Billy (sometimes “Willie”) Whitla was the big story.

The caption reads: A 1909 divided back postcard summarizes the story. Willie Whitla, Sharon, Pa., kidnapped March 18, 1909. Returned to his parents March 22, after payment of $10,000 ransom. Kidnappers arrested the day after in Cleveland, Ohio, and money recovered.”

Although this does not sound like the crime of the century, it got national play in newspapers. Undeniably cute, the eight-year-old son of a “prominent attorney” was taken out of school on a Thursday morning by a stranger and driven away in a buggy. That same day, the parents received the ransom note. Ten thousand in unmarked small bills was demanded. A warning prohibited giving the letter to the newspapers or divulging the contents. “Dead men tell no tales. Neither do dead boys.” Reply in the personal columns of any of four specified newspapers.

The parents replied in the affirmative. The getaway horse and buggy were rented locally and found in Warren, Ohio. The horse was noted to be “nearly exhausted.” The Whitlas refused to render any assistance to the police in fear for their son’s life. On Saturday, a letter in reply to the personal ad was written in handwriting of three people, a man, a woman, and Billy. Detailed directions urged the father to drop the money in an Ohio city park. The prescribed route was not followed, and no one showed up.

Another letter arrived on Monday. Coming to Cleveland on a certain train, a trolley to a certain intersection, and picking up a letter at a drugstore were detailed for Mr. Whitla. That message directed him to a confectionery store to deliver the money packaged for a Mr. Hayes. The storekeeper had no idea what was in the bundle, but she had a note from “Mr. Hayes” sending Mr. Whitla to a hotel to wait for his son.

The boy’s description had been widely distributed by this time. Two men saw Billy on a streetcar and took him to the Cleveland police. He appeared to be drugged, but joyfully recognized his dad at the reunion. The kidnappers had kept him docile with a story that Mr. Whitla asked them to take Billy away from home out of fear of a smallpox outbreak. Billy was to hide under the sink if the doorbell rang, because it might be a doctor arrived to take him to the pesthouse. Billy was amused at the idea of fooling the doctor.

On his return over the border to Sharon, Pennsylvania, a parade was organized, and the family home was serenaded for hours by local bands. Back in Cleveland, the criminal masterminds were noted by a saloonkeeper to be spending five-dollar bills to buy drinks for the house. On Wednesday the generous couple was arrested, drunk in another saloon, bragging about their perfect crime. The woman had the original packages of money concealed about “her person” ($9,848 in small bills hidden…where?)

Back in Cleveland, Billy identified them as the kidnappers. Their trial was held in another county, in fear of a lynching in Sharon. The man’s defense offered no testimony. Billy had seen the man with a mustache come for him at the school. Unusually adroit police work found the barber who had shaved off the mustache in nearby Niles, Ohio. The jury deliberations took only moments. The woman’s trial proceeded similarly the next day. The man died in prison; the woman served 10 years.

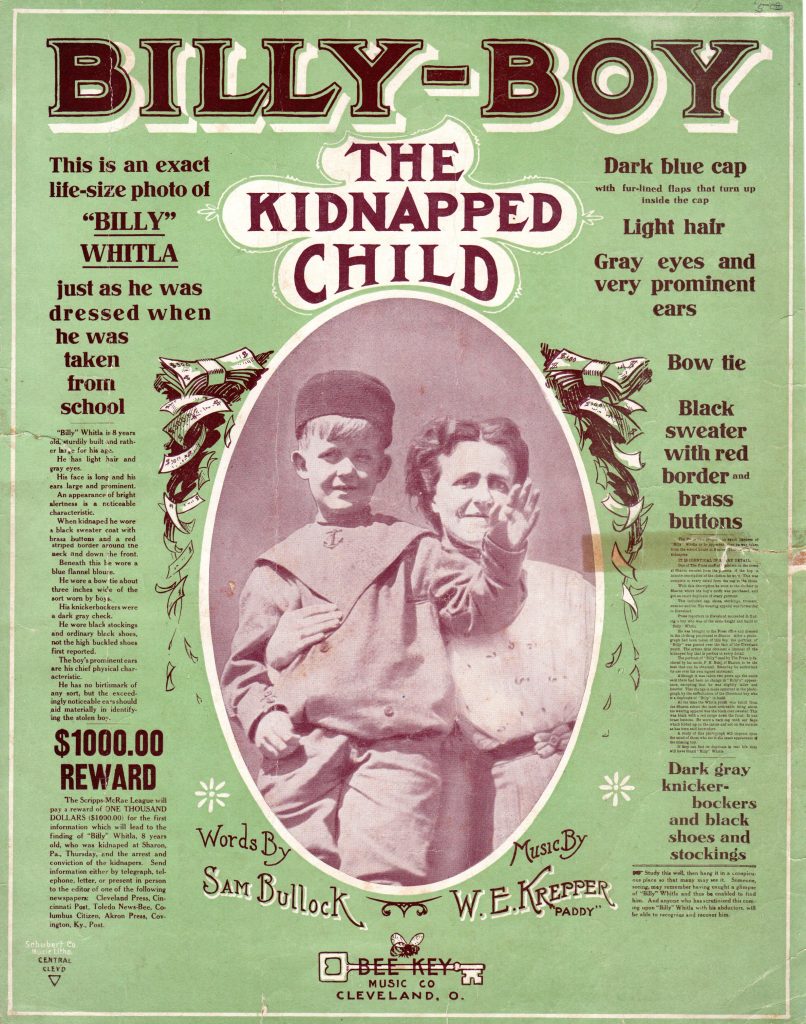

My postcard collecting is limited to cards that relate to other collections. In this case, I found a piece of 1909 sheet music, Billy-Boy, The Kidnapped Child. The unusual topic and odd cover were appealing. A violet photo of Billy was surrounded by text. A Cleveland music publisher wasted no time getting the music out. The cover would imply that the music was available before Billy was found, but this seems unlikely. Even the postcards were done after the fact. A book was out the same year. The boy was captive for only 4½ days.

The “life-size” photo of Billy Whitla on the music showed the boy waving, with a woman’s arm around him. He was dressed as he was at the kidnapping. A physical description and details of his clothes are listed. Larger print mentions “very prominent ears.” The Scripps-McRae newspapers offered a $1,000 reward for information, sent to any Scripps newspaper editor.

E. W. Scripps Company started in 1878 in Cleveland. Eventually, their newspaper holdings spread over the Midwest. They founded the United Press wire service and entered the radio and TV markets. Their foundation was the branch offering the reward. Scripps papers elevated Billy’s case into national prominence.

In finer print, the music cover urges the buyer to study the photo carefully. Someone had found an identical outfit and posed another boy the same age and size as Billy. That boy’s mother was the lady in the picture. They pasted Billy’s head onto the posed picture!

William Whitla became an attorney, married and lived in an imposing house next door to his parents. The homes remain in Sharon, Pennsylvania. Sadly, Billy died of pneumonia at age 31 nine months after the Lindbergh kidnapping. His New York Times obituary is mostly about the events of 1909.

The actual song is soppy-sentimental boilerplate.

A great article on an unusual postcard.

I grew up in suburban Cleveland, and this story has a ring of familiarity. Perhaps one of the local papers did a “looking back” feature on the case, or maybe I saw a televised treatment of the incident.