Jeremy Rowe

The Story of Johnson, Arizona

The development and popularity of the real photo postcard in the early 20

th century aligns with the boom, and occasionally the bust of many of the smaller mining communities in southern Arizona. The stories of the mining operations and towns that grew around them were often documented in real photographic postcards. One such town that exists today almost solely through a collection of real photographic postcard images that has been assembled by the author is Jonson, Arizona.

In 1909, F. H. Mitchell, the general manager of the Johnson Development Company, brought in new machinery to sink a mine shaft to 200 feet. This view shows the vertical headframe and hoist building that housed the 40-horsepower gasoline engine and air compressor to power air drills behind the tailings of the Johnson Developing Company mine in Southeastern Arizona.

Mining operations in the southeastern corner of Arizona began on the east side of the Little Dragoon Mountains in Cochise County in about 1881, when the Peabody, Republic, and Mammoth mining claims led to the establishment of Russellville. The copper camp of Johnson initially grew slowly nearby, eventually justifying the establishment of a post office in 1900. Growth of the little town of Johnson quickly surpassed Russellville, and quickly reached a population of 317 in 1902.

The Johnson Copper Development Company was soon capitalized at $300,000, and Colonel Greene purchased claims and established the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. Both mines were soon shipping a carload of high-grade ore to a smelter in El Paso, Texas by rail every day. The

Bisbee Daily Review noted, “Johnson will take on a new life and undoubtedly add another producing camp to Arizona’s list of big producers of copper.”

In May 1909, the Black Prince group struck a body of sulfide ore that yielded 25–35 percent copper at a depth of 430 feet. The Centurion mine found ore at a depth of 160 feet that yielded 25 percent copper.

By 1910, the Peacock Copper Mining Company had erected a hoist and had two carloads of ore ready to ship. The Arizona United Mines Company built and ran its own 125-ton smelter, and it, the Centurion, and Black Prince were all regularly shipping ore for processing.

The year 1916 saw the largest output of the mines at Johnson. The Cobriza Company was shipping four cars of ore a day. The Arizona Michigan mine shipped one or two cars a day to the smelter at Douglas, and the Peabody Mine was shipping about three carloads of ore a week.

Active groups at Johnson at this time included the Black Prince Mine, Peacock Mine, Arizona Copper Shipping Company, Arizona and Michigan Company, United Mines Company, Keystone Copper Company, St. George Mining Company, Cochise Development Company, Johnson Copper Development Company, Sims Mountain Copper Company, Centurion Company, and Empire Copper Company.

An itinerant young photographer, Dale T. Malonee traveled throughout Arizona from about 1916 – 1920. Malonee visited Johnson to document the productive mines and growing community in 1917. He and several other photographers produced a series of real photo postcards of the mines and growing town of Johnson during this boom.

The Johnson District was able to avoid the labor unrest that hit Bisbee, Clifton, and other mining communities soon after America entered World War I on April 6, 1917.

By 1918, mining production around Johnson continued to be strong, with Arizona United Mines typically shipping four carloads of ore a day from Johnson by rail to the smelter at El Paso.

By 1925, the population of the town of Johnson had reached nearly 1,000, but the dropping price for copper that continued in the economic turmoil that began after World War I led to cutbacks at the mines, and triggered emigration from Johnson to other more successful mining communities. The post office at Johnson closed in 1929, and Johnson was well on the path to becoming a ghost town. Years later, there was a brief resurgence in the region, when copper, zinc, and silver mining resumed after World War II.

Today, little is left of Johnson, Arizona other than a small ephemeral group of real photographic postcards that were made by itinerant Dale T. Malonee and anonymous photographers.

(Extract from Southern Arizona Mining by Jeremy Rowe, by Arcadia Publishing, 2023)

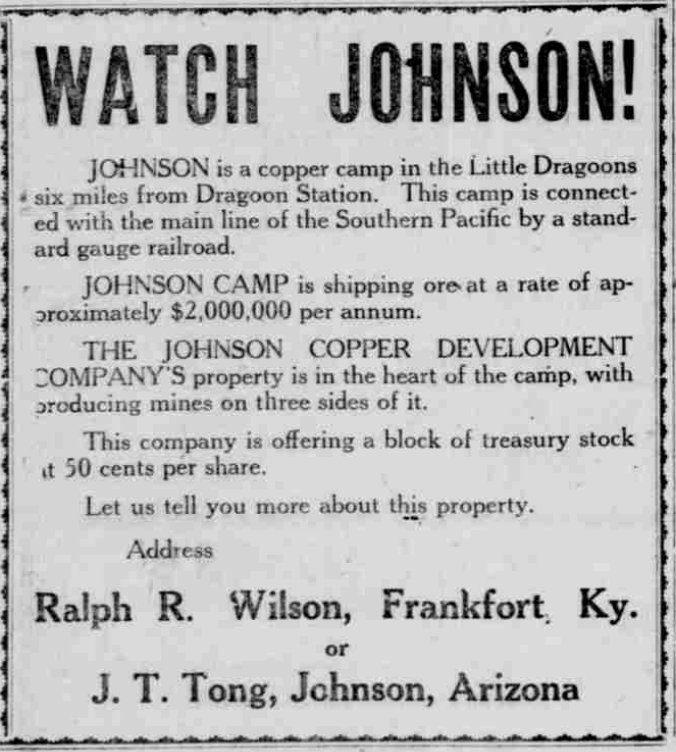

2. This booster ad was run on May 14, 1916, by J. T. Tong in the Bisbee Daily Review. The ad promoted the camp and its productivity stock offerings for his company in Johnson, Arizona. (Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.)

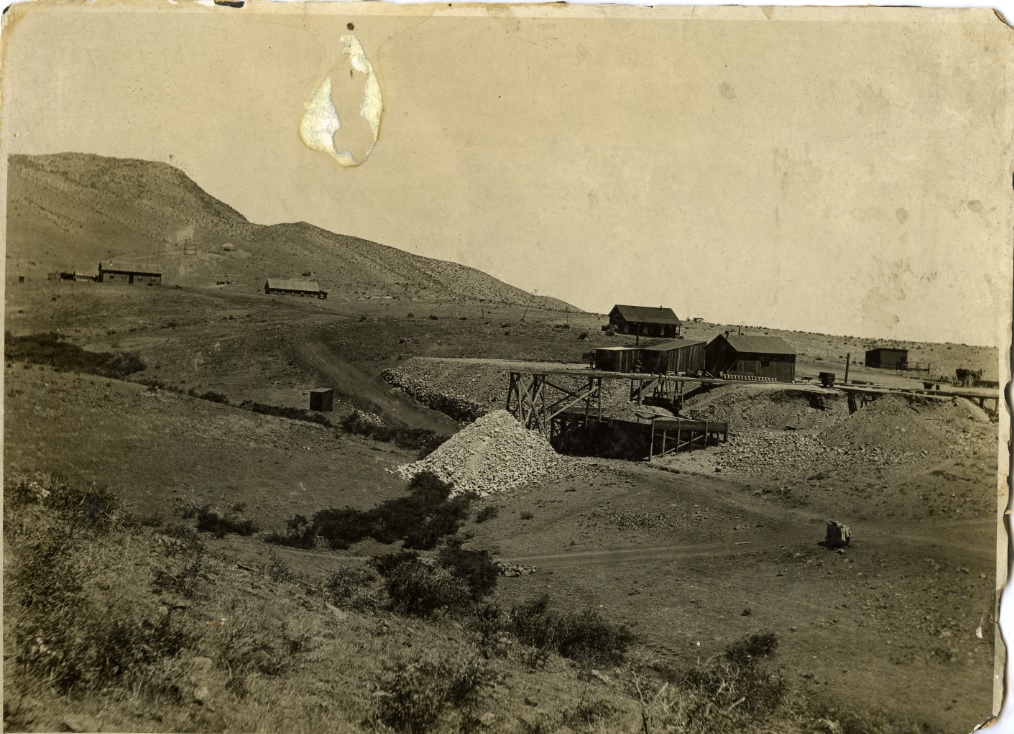

3. The hoist, engine house, and operation at the Black Prince Mining Company were in the foothills of the Dragoon Mountains about a mile north of Johnson. In 1909, the 160-foot- deep Centurion Shaft at the Black Prince struck a rich, six-foot thick, 25–35 percent copper ore vein at 430 feet that produced ore at 25 percent or better copper. But by 1915, only 10 men were working at the mine.

4. The Republic Mine at Johnson was operated by the Cobriza Mining Company. Note the large fresh slag heap of material removed from the mine in the foreground.

5. The Cobriza Mining Company shipped up to 5,500 pounds of ore a month from its operations at the Republic and Mammoth Mines in the Johnson District. In 1916, the company grew its operation by purchasing the 60-acre smelting plant and silver and lead slag dump at Benson, Arizona.

6. The Arizona United Mines Company built a 125-ton smelting plant in 1909 to expand capacity as mining in Johnson output grew. The smelter closed in 1916 when the Southern Pacific Railway attempted to raise shipping costs for ore from Johnson. After transportation rates were stabilized by the Arizona Corporation Commission, the smelter resumed operation.

7. In 1912, increasing prices for copper drove even greater mining activity in the Johnson District. The town had grown to three miles long and was a mile wide from east to west on the eastern side of the Dragoon Mountains. This overview shows a mix of rapidly constructed temporary wooden and canvas residences that interspersed the more permanent wooden structures that made up the town of Johnson during this era.

8. Housing in the rapidly growing mining communities of southern Arizona needed to be built quickly and varied dramatically in scope and sophistication. This image shows a thatched hut that was a far cry from even the typical simple canvas and pallet temporary housing for miners during this era, let alone the more formal wooden structures that followed as the towns adjacent to the mines grew.

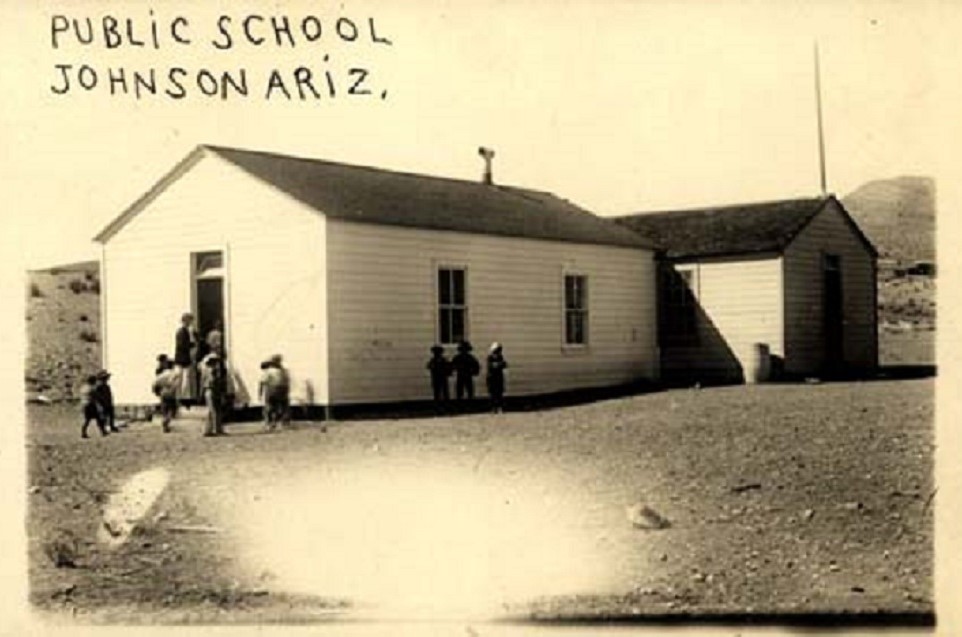

9. As families joined the communities, amenities like schools and churches were built. This image shows the new one-room schoolhouse that was built at Johnson, led by female principal Mollie Brown who is posed in the doorway.

10. This view is looking north across the Johnson townsite. The period manuscript identifications include J.T. Tong’s home, Old Lady O’Hara’s house, the Picture Store, and the lumberyard. Note the headframe of the Johnson Development Company behind the town on the left.

11. This view looks down the Main Street of Johnson, Arizona from the storage buildings at the edge of town. Manuscript locations noted include Wen & Stein pool hall (one of three in Johnson), a restaurant (Perry & Sons), a barbershop (A.L. Martin), T.B. Larkin’s rooming house, A.H. Wein’s general store, Albert Thurman’s meat market, William Seliger’s Picture Show, and B.A. Taylor and L.W. Rader’s general store.

12. Johnson had some of the richest and purest deposits in the United States at the beginning of the 12tungsten boom. An assay of one deposit was valued at $19,000 per ton of ore.

13. This is probably a view of the Primos Chemical Company operation about five miles from Johnson. The boom eventually led to surpluses of the precious metal and dropping prices.

Photo credits:

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS ARE PART OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION, © vintagephoto.com.

1. Photo by Dale T. Mallonee, c. 1917.

2. Newspaper ad.

3. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

4. Silver print, photographer unknown, c. 1917.

5. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Mallonee, c. 1917.

6. Cropped real-photo postcard by Dale T. Mallonee, c. 1917.

7. Real- photo postcard, photographer unknown, c. 1915.

8. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

9. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

10. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

11. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

12. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

13. Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917.

There are also many villages in New York that have disappeared but live on in real photo postcards. When construction began on the Ashokan Reservoir in 1907 eleven hamlets in Ulster County were flooded or relocated: Ashton, Boiceville, Brodhead’s Bridge, Brown’s Station, Glenford, Olive, Olive Bridge, Olive City, Shokan, West Hurley, and West Shokan. Hundreds of houses, barns, mills, farms, churches, shops, and schools disappeared. In 1908, the village of Delta was covered by Delta Lake in the Town of Western, in Oneida County.

Yes, and the village of Katonah, NY was flooded when the Croton Reservoir was built.

Fascinating look at a boom town now lost to time.